Recent archival scholarship has explored the intimacy of “archive stories” that narrate “how archives are created, drawn upon and experienced by those who use them” (Burton 6). Together with the short film, “Traces in the Script,” this essay constitutes a single integrated exploration of a diverse group of users’ creative, scholarly, and personal interactions with a particular archive, that of Newcastle-based feminist theatre company Open Clasp (http://openclasp.org.uk/). Made by Kate Sweeney, a long-time collaborator with Open Clasp, the film is itself a creative response to that archive, exploring two performers’ engagement with archival materials that thematize complex relations between intimacy and distance and document their own creative practice. This multi-dimensional publication embodies our aspirations to collaborate in a way that fosters a wide range of palimpsestic possibilities, allowing different voices, media and stories to co-exist in creative and critical spaces enabled by interaction with this archive. The archive itself, this essay and the film are all rooted in Catrina McHugh’s work as Open Clasp’s writer and artistic director. Kate Chedgzoy and Rosalind Haslett bring to this collaboration expertise in theatre history, archive studies, and feminist scholarship which has informed dialogues with McHugh and Sweeney about the archive’s history and potential futures. All four of us co-wrote this essay as part of a larger collaborative process, key participants in which are named below or in the film’s credits. We have sought to demonstrate how creative-critical collaborative methodologies can resonate with the interaction of intimacy and distance in the making, experience and archiving of theatre.

The issues we consider have also been richly explored by creative practitioners and scholars in recent years. A sense of intimate connection with particular archives is generated in creative undertakings like the Greenham Women Everywhere collaboration between feminist theatre company Scary Little Girls and online publication The Heroine Collective (greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk), and the Rebel Dykes project encompassing art, archive and documentary film (rebeldykeshistoryproject.com). The boundaries between scholarly, creative, and personal writing have been blurred in the first-person narratives produced by researchers reflecting on their experience of engaging with archives already constituted, located and accessed within an institutional setting (Steedman). Archival intimacies are invoked in a different sense by Maryanne Dever, Ann Vickery, and Sally Newman, who consider the ethical and methodological challenges posed — particularly for feminist scholars studying women’s archives — when the processes of archiving or researching reframe private, personal documents as a publicly accessible archive, a process which, they argue, inevitably installs a certain distance between the creators and users of the archive, the nuanced self-reflexivity of much contemporary practice notwithstanding (Dever et al.). This essay, film, and photographs emerge from an evolving collaborative relationship between academics and creative practitioners that aims to provide a new institutional home at Newcastle University for the Open Clasp archive. We invoke intimacy and distance as analytical concepts that enable us to consider the ethical and affective inflections of the creative, intellectual, social and spatial dimensions of our collaboration. As we work together, we explore how these concepts inform the interwoven process of simultaneous archiving, researching and creative making in which we are engaged.

Open Clasp makes impactful professional theatre for social change, grounded in participatory work with women and girls. The company draws out and amplifies the voices of women whose lives are shaped by their gender as it intersects with class, poverty, race, sexuality, refugee and asylum-seeking status, and with experiences of domestic violence and the criminal justice system. In an email conversation among the authors, McHugh explained how they work:

We embed ourselves in communities... Our process is to carve out spaces for women to come together [in participatory workshops] to talk, discuss and debate, to grow in confidence and self-esteem, a space for consciousness to be raised. The workshops inspire scripts and plays to be produced, we tour to audiences nationally and internationally.

The company’s archive speaks to all aspects of this work. It contains images, objects, and a hugely diverse body of written texts and documents, including financial records which expose the challenges of running an independent theatre company; material produced by women who participated in creative workshops in prisons; research notes; character profiles, script drafts and storyboards; documentation of tour planning and promotional activity; and audience feedback from performances. These varied materials constitute a deeply personal record of McHugh’s sustained creative and emotional labour over more than two decades, which has enabled the company to build relationships with collaborators, audiences and participants that extend its reach across cultural, institutional, organisational and geographical distances.

Open Clasp’s offices are based in the West End Women and Girls Centre (WEWAG), a community centre in a socio-economically deprived area of Newcastle with a very diverse population. McHugh works alongside her wife Huffty McHugh, manager of WEWAG, and their union is a literal and metaphorical centre for the affective work of both organisations. Accumulating over time and inhabiting interstitial spaces within the WEWAG building, the archive currently dwells in intimate proximity to the community Open Clasp works most closely with, but is not accessible to it. The beautiful notebooks in which McHugh handwrites creative drafts and planning notes are stashed in desk drawers, files are shelved behind team members’ desks, and memories of past productions are stored in boxes of documents and objects in the attic. “Traces in the Script,” the film that forms part of this submission, works to unfold the archive’s present life in those spaces, and thereby to demonstrate the potential of creative practice to share it with the company’s most proximate communities

In September 2017, Open Clasp generously offered to gift its archive to Newcastle University in order to ensure its preservation and long-term accessibility to the public, thereby opening up new possibilities for creative, educational, and scholarly interaction with it. But the Library is a half-hour journey by public transport from WEWAG, so there will be a spatial dislocation; and the move will create a cultural distance between the archive and its use by the women Open Clasp works with, to whom intangible but powerful understandings of the university’s place in the city make it remote and inaccessible. As feminist scholars, Haslett and Chedgzoy seek to work with McHugh, Sweeney, and other members of the Open Clasp community to narrow these spatial and symbolic distances and to ensure the archive’s eventual move into the university does not seal it off from wider engagement. However, they are conscious that they approach the archive as outsiders, approaching it from a particular institutional location and bringing to it a set of scholarly concerns that resonate with but are distinct from Open Clasp’s priorities. The authors seek collectively to recognize and address this potential source of tension in the multiple dimensions of the present publication, which is driven by a set of research questions and priorities that have emerged from the dialogue and collaboration between the four authors over a period of time. Conceptually, we have been influenced by feminist standpoint theory, which as Michelle Caswell argues provides a rich resource for researchers working with archives across the disparities of power and privilege that shape our collaboration (Caswell). As academics working with creative practitioners in a sensitive and dynamic context, Chedgzoy and Haslett have sought in this process to act on Caswell’s call for the archivist to act as “a socially located, culturally situated agent who centers ways of being and knowing from the margins” (Caswell 2). Sensitivity to the issues raised by Caswell is important because, as McHugh said in an interview, “Women have trusted the company with their stories. What does archiving them mean? Who will benefit from it? We [. . .] don’t want to just give it to a university so that people who have more opportunities gain from looking at it” (Sinclair). These words highlight the need to be attentive to the differences of scale, location, mission, wealth, and power that create distance between Newcastle University and Open Clasp; and at the same time, they evoke the intimacy and vulnerability always present in Open Clasp’s work with women. They thus delineate the specific challenges faced by our shared effort to develop this archive across and between these very different contexts.

Developing trust with a full awareness of both what connects and what distances the collaborators is consequently a crucial aspect of our collective journey. Navigating epistemological, ethical and organisational challenges, we seek to work in ways that embed Open Clasp’s ethos-driven, community-based and responsive values. To date we have tested out ways of doing this through three strands of activity:

There are layers of collaboration in play here and the interplay of intimacy and distance resonates across all three strands. In what follows, we map what each entails and consider how the palimpsestic vision of the archive created by combining them may spark new possibilities for creativity, analysis and insight as we continue to collaborate around the Open Clasp archive.

Alongside their studies, Newcastle University students Maria Athanasiou, Simone Gaddes and Megan Ayres made weekly pilgrimages to the Open Clasp office in the West End Women and Girls’ Centre. They rummaged among boxes in the attic, brought them down to list their contents meticulously, and pored over creative notebooks, production feedback, funding applications and touring schedules. Their training in archival skills by Rachel Hawkes and Danielle McAloon of Newcastle University’s Robinson Library enabled them to produce a meticulous and insightful box log that will facilitate cataloguing and support the development of research outputs and funding applications. Equally valuable is the development of an affective collaborative relationship enabled by their presence in the office, vividly illustrated by Gaddes’s delight one summer afternoon at the gift of a bagful of beans grown on the WEWAG allotment, a gift that well expresses the archive’s nature as a multi-sensory repository, containing objects as well as documents, that can be encountered in various ways.

Athanasiou, Ayres and Gaddes have gained insights from seeing and touching the archive in the place that made it and benefited from opportunities for capturing tacit and communal knowledge about the company and its ways of working. This has been a work of co-creation founded on close collaboration between Newcastle University students and the Open Clasp staff members who have welcomed them so warmly and shared their workspace so generously.

The choice to investigate the archive on-site was a response to McHugh’s explanation, in an email to the co-authors in September 2019, that she began to develop her own understanding of what an archive might be through encounter, relationality, affect and conversation: “I liked hearing Kate [Sweeney’s] thoughts pour out of her head and onto the table, of teapots and leaflets held by Palestinians, crumpled and placed in boxes. How those leaflets unfolded years later enabling a living archive of voices, all sharing the same moment, of bombs falling and cities being destroyed and survival.” She was reflecting on a tea-fuelled project planning meeting in which Sweeney had shared her own intense response to theatre-maker Rabih Mroué’s “Warning,” which traces his iterative attempts to create an archive documenting his experience of undergoing Israeli bombing in 1982. Across significant distances of time and place, McHugh’s words enact a deep connection and recognition of the resonance of Mroué’s work for our own archival labour. By recalling a specific conversation, she evokes the intimacy created by the very existence of Mroué’s precarious yet rich “living archive” of the everyday, and by the process of thinking and talking about it. Her articulation of her own process of learning from other situations, archives, and experiences informs our shared commitment to creating an archive in which diverse voices can be held and amplified.

On a warm June day in 2019, more than 60 women — arts practitioners, academics, members of community groups and organisations with which Open Clasp has partnered — gathered at WEWAG. We came together to celebrate the company’s twenty-first birthday by sharing materials from the archive, reflecting on the stories and experiences it holds, and discussing how we might collaborate to open the archive to a wide range of users and purposes. Some of the participants had longstanding close relationships with the company, and a web of established connections among them was already woven through the room; others had travelled long distances and needed to be drawn into that web. Applied theatre researchers have highlighted the importance of ethical sensitivity in eliciting the voices of participants who inevitably become collaborators (Nicholson 20), so we took care to secure the explicit affirmative consent of everyone present to draw on their contributions in developing this project. These contributions took many forms: multisensory engagement with the stimuli provided by objects, documents, and recordings; participation in group sharing and discussion; live-tweeting of the event with the hashtag #OpenClaspOpenArchive, which extended the conversation beyond the room; opportunities for dialogue between creative practitioners and community activists; and Phyllis Christopher’s gorgeously insightful photographs, which illustrate this essay.

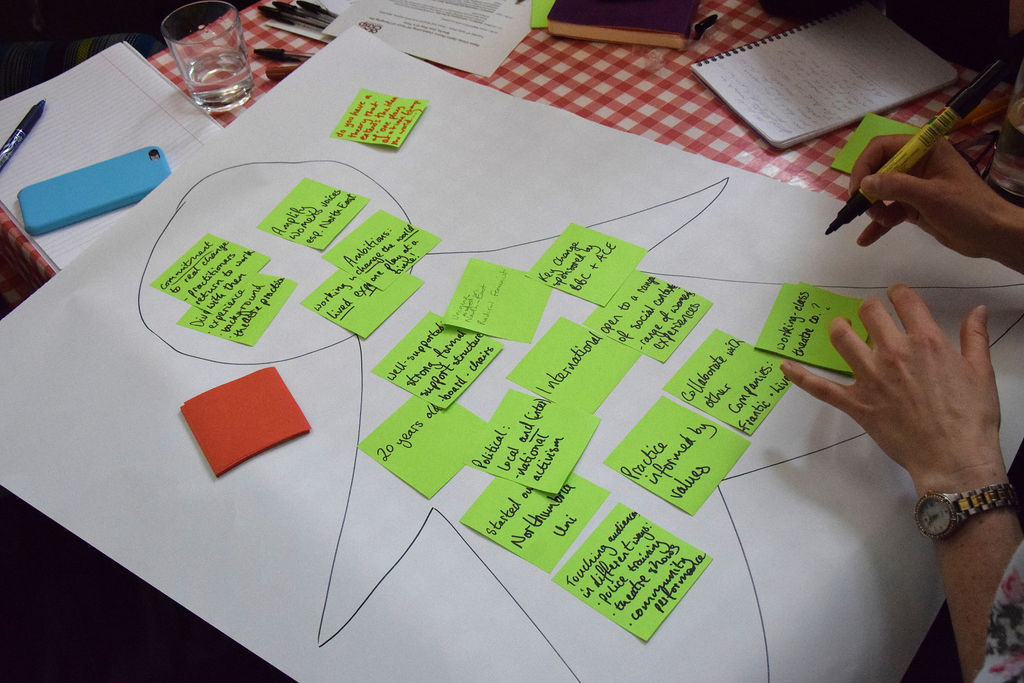

At the heart of this event was an exercise in the coproduction of knowledge, in which McHugh invited us to imagine Open Clasp as a woman in order to gather and share information, reflections, memories and feelings about the company. In small groups, we clustered around flipchart sheets marked with a stylised shape that bodied forth Open Clasp, wrote responses on post-it notes to a set of prompts offered by McHugh that invited us to imagine the company as a woman with a history, feelings, and dreams for the future, and stuck them to the sheets.

This activity generated a moving and revealing discussion that both responded to the company’s archive and generated new material that has entered it. Some women had deep and intimate histories with the company, as participants in prison workshops who later became creative collaborators, or as audience members empowered to make transformative life decisions by seeing stories they recognized on stage. Other women drew on experience as practitioners or community activists to highlight the material difficulties a small independent theatre company has to surmount, or foreground Open Clasp’s vital role in the intricate networks of mutual support that sustain organisations working with women in the North East. Many noted the crucial grounding of the company’s output in its trust-based participatory work, which enables women to share deeply personal stories, transforms them into powerful theatre, and uses that as a tool for social change.

The depth and delicacy of participants’ responses to these prompts was facilitated by the warm hospitality offered by Open Clasp and WEWAG. Participants were welcomed to a bright room decorated with evidence of the company’s activities over the years, and we began the day, at McHugh’s invitation, by exchanging warm individual greetings. We shared a delicious lunch provided by the WEWAG kitchen team, ending the event with a huge pink cake to celebrate Open Clasp’s 21st birthday.

In choosing to centre a shared meal and a celebratory cake in the event, we drew purposefully on Nicola Shaughnessy’s observation that the “conjoining of performance with communal eating is part of a tradition which extends into applied performance” (Shaughnessy 23). Hospitality as a creative practice makes and values community: it resonates with the nature of this symposium as a birthday party, a life-cycle event celebrating the woman the company has become, expressing the sense that the company and its community form a chosen family. Families are not homogenous communities, however, and family archives can constitute contested spaces for memory work where multiple voices need to speak and be heard. The photographs included in this essay and the Twitter activity documenting the event (@openarchive1, #OpenClaspOpenArchive) depict both celebratory reunions and differences of perspective.

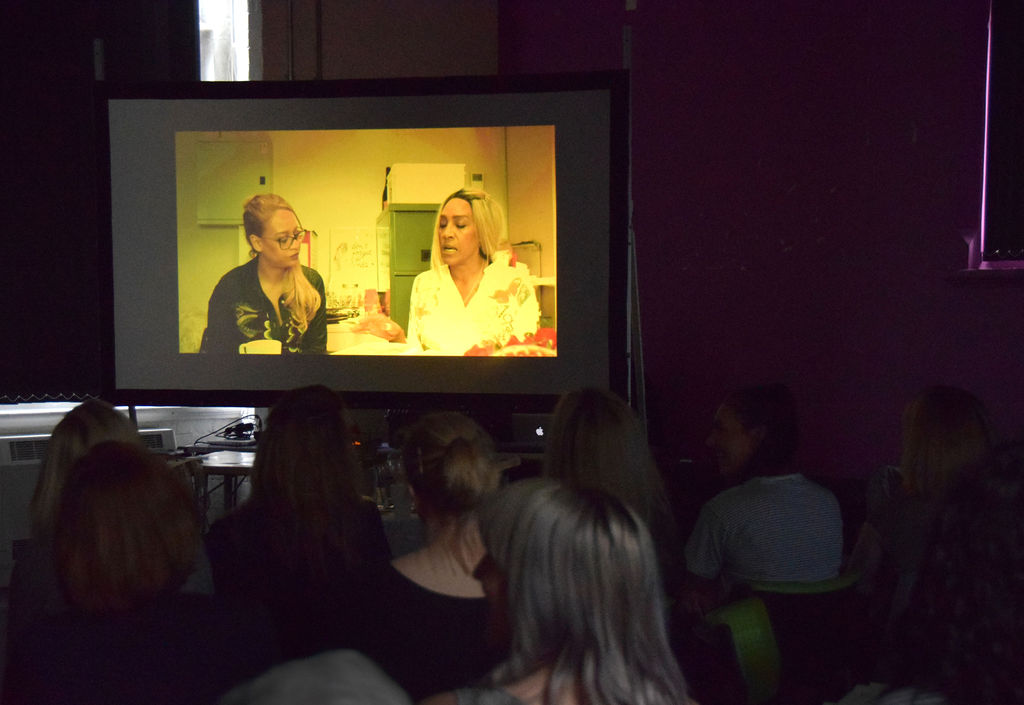

The film Traces in the Script investigates the gestural, conversational, collaborative and anecdotal aspects of the Open Clasp archive — intimate, fugitive things that cannot easily be held by the materials themselves. Taking as its model Open Clasp’s commitment to collaborative process and to telling stories that have been hidden or overlooked, it is a work of co-creation with mother and daughter performers Abigail Byron and Cheryl Byron, filmed discussing their experiences of making the Open Clasp production don’t forget the birds (2018), which explores the impact on their lives of time Cheryl spent in prison. The film thus depicts a lived experience of familial intimacy ruptured by the distance violently inflicted by a prison sentence, and the rebuilding of that intimacy — affective labour that was supported by the Byrons’ collaboration with Open Clasp on the making of don’t forget the birds. Working in full awareness of this complexity, Sweeney conceptualised the film as an archival document: one that simultaneously contributes to and reflects on Open Clasp’s archive, but also one that because it is being published online may be appropriated into many different archives in ways that exceed the creators’ control. Consequently, she felt a keen responsibility to construct the film in a way that safely held the intimacy that shaped her collaboration with the Byrons, and shielded the vulnerability they revealed with an appropriately protective distancing:

The process of editing the film was a delicate balance of preserving and highlighting things said and things gestured with body language, of interpretation and decision-making about what was important, and of what needed to be left out. Unpicking, cutting up and re-stitching together the interview felt both a form of care and protection, and an interference and manipulation (Sweeney).

Traces in the Script functions simultaneously as a response to archival material, a document of a collaborative process, and an intervention in debates about archive theory and practice. Its status as a piece of creative practice research is crucial to its “valuing of intimate moments of encounter in a creative process” (Hughes and Nicholson, 6). Undertaking such research is a complex, sensitive, interactive process, and questions of how to frame and distribute the film, who can claim authorship of it, and how best to credit all the different contributors have generated fruitful discussion among the collaborators of ethical, creative and intellectual issues crucial to the larger collaborative process in which we are collectively engaged around Open Clasp’s archive. Ann Cvetkovich evokes the distinctive potential of “new documentaries [to] create affective archives […] that can acknowledge traumatic pasts as a way of constructing new visions for the future” (Cvetkovich 14). Sweeney’s methodology and aesthetic thus lend themselves perfectly both to documenting Open Clasp’s activity and to opening up uses of its archive to enable women to generate such new visions. Her work will be key to the continuing process of archiving and to future activities responding to the Open Clasp archive.

Open Clasp’s archive documents a sustained feminist commitment to making audible stories and voices that are rarely heard publicly or endowed with cultural value. As a body of work produced by, with and for women, it offers a rare gift to feminist archival scholarship. At the heart of our collaboration is the dual desire to use the archive to create new opportunities for women to engage with Open Clasp, and to explore creative, ethical, innovative methods for archival research. We work with a conceptualisation of the archive as not so much a repository but a self-renewing resource; one that is held protectively enough to enable us to open it up to use as a space where intimacy and distance can be acknowledged as shaping factors in the ways archives are created, accessed, shared, and preserved.

Burton, Antoinette. “Introduction: Archive Fever, Archive Stories,” Archive Stories: Facts, Fictions, and the Writing of History, edited by Antoinette Burton, Duke University Press, 2005, pp. 1-23.

Caswell, Michelle, “Dusting for Fingerprints: Introducing Feminist Standpoint Appraisal,” in “Radical Empathy in Archival Practice,” edited by Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, Jasmine Jones, Shannon O’Neill, and Holly Smith. Special issue, Journal of Critical Library and Information Studies. 3, 2020, 1-36.

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Duke University Press, 2003.

Dever, Maryanne, Ann Vickery, and Sally Newman. The Intimate Archive: Journeys Through Private Papers. National Library of Australia, 2009.

Hughes, Jenny, and Helen Nicholson. “Applied Theatre: Ecology of Practices.” Critical Perspectives on Applied Theatre, edited by Jenny Hughes and Helen Nicholson. Cambridge University Press, 2016, pp. 1–12.

Mroué, Rabih. “Warning,” in Lexicon for an Affective Archive, edited by Giulia Palladini and Marco Pustianaz. Intellect, 2016, pp. 41-50.

Nicholson, Helen. Applied Drama: The Gift of Theatre. Palgrave Macmillan, 2014.

Rebel Dykes History Project CiC. Rebel Dykes. https://rebeldykeshistoryproject.com.

Scary Little Girls and The Heroine Collective. Greenham Women Everywhere. http://greenhamwomeneverywhere.co.uk.

Shaughnessy, Nicola. Applying Performance: Live Art, Socially Engaged Theatre and Affective Practice. Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Sinclair, Tracey. “Open Clasp: Celebrating 21 Years of Changing Women’s Lives Through Theatre.” https://thestage.co.uk/features/interviews/2019/open-clasp-celebrating-21-years-of-changing-womens-lives-through-theatre/.

Steedman, Carolyn. Dust. Manchester University Press, 2001.

Sweeney, Kate. Traces in the Script. https://capturingthebody.wordpress.com/2019/06/17/traces-in-the-script/.