The COVID-19 pandemic intervened at a moment that was nearly synchronous with protests in cities around the world. Diverse publics in Hong Kong, Santiago, Beirut, Barcelona, Baghdad, London, and across the United States demanded policing reforms, climate action and the safeguarding of democratic governance. Lockdowns, social distancing, and quarantining were not in themselves responses to these movements, but they conveniently dampened unrest, highlighting the volatility of bodies gathering in public space and technology’s role in governing individual subjects. As governments struggled to respond to virus trend lines, millions found themselves jobless, the stock market soared, Google search terms mapped viral spread, and scientists analyzed data samples.

The spread of the virus also redrew ambiguous boundaries between material and immaterial labor into starker distinctions between essential and non-essential workers. Non-essential workers took refuge at home, while essential labor continued in-person work as the “living infrastructure” (Jackson) of a globalized economy. The upheaval highlighted the instability — and interdependence — of social, technological, and economic networks, as well as the global economy’s reliance on their uninterrupted functioning. As (some) humans sought to protect themselves from a biological threat, digital communication technologies came into full view as a lifeline keeping people safe, connected, and productive. With so many relying on stable internet connections and personal computers for their lives and livelihoods, the virus showed how uneven access to digital infrastructures was a question of economic and political equity.

One of the most consequential developments arising from this urgent move online was the retreat into the tele-conferencing platform Zoom Video Communications, a California-based company founded in 2011. What provoked such a sweeping adoption of a single platform? Why Zoom? Zoom worked because it was simple; it integrated easily into existing platforms (Slack, Microsoft Outlook, Canvas, Moodle) and could be launched with the click of a single URL. While other interfaces — Skype, WhatsApp, Facetime, Microsoft Teams — appeared long before Zoom or were supported by companies with broader initial brand recognition, none were able to so quickly and broadly capture the public’s attention and continuously introduce new features. With a packaged suite of services all focused on the goal of connecting a globalized labor force, Zoom promised high quality, cost effective, easy to deploy, scalable video communications that would “improve efficiency,” “boost productivity,” and “enhance internal collaboration” (Zoom). The promise of this singular and seemingly straight-forward service quickly attracted hundreds of millions of users and became a shared “place.” Like the virus itself, a network effect meant that Zoom propagated exponentially with each individual who connected. Zoom became, at once, a “critical infrastructure” for business (Villasenor) and a cultural phenomenon that transformed how we stay in touch and work together across varying distances. Indeed, on its homepage, the company assures us that we are “In this together” (Zoom). And Zoom was there, waiving its fees for schools during the pandemic, lifting its 40-minute time limit over the winter holiday season, and adding a “Home” version for those working remotely.

As non-essential labor, the performing arts also took shelter in Zoom, using the platform to remain productive as creative laborers. Zoom served as rehearsal room, stage, and collaboration space. The platform answered a need to sustain creative practices and ensure this work would remain vital, if not “essential.” We situate this discussion of Zoom’s impact on the performing arts within the context of theories of network culture and immaterial labor. Zoom’s screen environment entangles and contains space, labor, and performance in ways that amplify the enclosures of network culture. Time, attention, and affect circulate within Zoom’s limited field, further abstracting labor, environments, subjectivities, and our relations to each other. Importantly, Zoom’s increasing capacity to capture and quantify the collaborative exchanges that take place within its enclosures comprises an important technological extension of these abstractions. Its promises to “deliver happiness” and provide a space of safety, security, and connectedness obscure the ways in which the software is designed to instrumentalize relations between people and capture data that quantifies and rationalizes human behavior. With this in mind, we wonder: What can performance practices do with and within Zoom’s spaces?

To develop this inquiry, we look at three performances that experiment with the platform: a three–part work titled End Meeting for All by UK theatre company Forced Entertainment; the performance lecture Is this Gutai? by the Taiwanese artist River Lin; and a Zoom workshop entitled The F/OL|D as Somatic/Artistic Practice by one of the contributors to this paper, Susan Sentler, and her collaborator Glenna Batson. These works were selected because they slip between performative genres and affective registers and because they challenge Zoom and its protocols. Stretching Zoom’s prescribed functions and “universal” design, the examples thwart expectations of productivity and efficiency. They assert the slipperiness of performed subjectivities and collaborative exchanges and suggest how Zoom trains certain kinds of techniques — of interaction, attention, and affect. Through this play with Zoom, they reveal how intimate engagements with technological infrastructures provide shape, meaning, and access to the networks that sustain us. We offer starting points and provocations for thinking through these interactions, while recognizing that Zoom’s functionality continues to expand, enveloping additional aspects of communication in the name of user experience. It is perhaps impossible to keep up with Zoom. Nevertheless, challenges to its suite of logics and protocols offer lessons that, brought forward, could inform artistically-led collaborations.

As a concept, immaterial labor has drawn attention to the affective, cognitive, and creative labor not immediately visible as part of the production of commodities. In an essay that framed the discussion, Maurizio Lazzarato describes immaterial labor as “labor that produces the informational and cultural content of the commodity” (133) and “produces first and foremost a ‘social relationship’ (a relationship of innovation, production, and consumption)” (138). Activities as diverse as coding algorithms, providing care, and “liking” a Facebook post produce informational and cultural content that expands at the same time it is consumed.[1] When we like a post, we effectively become collaborators sustaining Facebook’s production and enlarging the corporation’s capacity to capture and commodify subjectivities and social relations. Likewise, when we enter Zoom’s rooms, we become its laborers; the more we work (and play) in Zoom, the more Zoom consumes the products of our labor in the form of data that is fed back into its networks and distributed across those systems with which it is connected (whether a learning management system, YouTube channel or company website). This expansion allows new technological processes to capture collaborative exchanges that comprise “free labor” (Terranova) and produce knowledge. Communication becomes reoriented away from “language and the institutions of ideological and literary/artistic production” and is instead “reproduced by means of specific technological schemes (knowledge, thought, image, sound and language reproduction technologies) and by means of forms of organization and ‘management’ that are bearers of a new mode of reproduction” (143). As Tiziana Terranova explains, free labor “highlights the existence of networks of immaterial labor and speeds up their accretion into a collective entity,” thereby leveraging their capacity to create new knowledge. Importantly, free labor “nurtures, exploits, and exhausts” a worker’s affective ties both to the production of this knowledge and to the kinds of bonds created when we work together (Terranova, “Free Labor” 51).

To consider the technological enframing of immaterial labor, we might recall two historical works in which performance practice comprises the capture of bodies. Bruce Nauman’s Walking in an Exaggerated Manner Around the Perimeter of a Square (1967-68) and Samuel Beckett’s Quad (1982) consist of laboring bodies pacing within delimited areas, a fixed technological frame enclosing both bodies and space. In Quad, the camera is “Raised frontal. Fixed” (Beckett 293), while in Walking the camera’s point of view encloses the detritus of Nauman’s studio. Mediating technologies — film and televisual broadcasting — at once make possible and circumscribe the works, enclosing artistic practice. The “cultural content” of the work exists because of this mediation and reproduction, thereby making that reproduction critical to immaterial labor’s capacity to produce a “social relationship” between performer and viewer. The two-dimensional screen, the physical spaces of performance (i.e. the artist’s studio or the production stage), and the technologies that allowed for their reproduction come together to form what architectural theorist Jennifer Ferng aptly calls a “screen environment.” Her reflection that “Zoom has heralded a new paradigm for users,” in which “the architecture studio exists as a paperless combination of the drafting board, desktop, and model shop” (208) makes it possible to consider how, in these earlier works and today through Zoom, the tools and spaces of performance — bodies, studios, props and stages — comprise an enclosure that coordinates distant spaces into a singular, totalizing assemblage, thereby expanding its claim to these sites and subjectivities.

Inhabiting screen environments provokes an exhausting self-consciousness that we are “performing” our work. Questions of stagecraft — camera angles, lighting, backgrounds — add to preexisting concerns about how we present ourselves. Ferng proposes that we “are now expected to inhabit a live fourth wall that perpetually moves from one Zoom window to another” and argues that “[t]his fourth wall — a site of rehearsed speeches, slide presentations, and chat messages — embodies the interface through which we must channel every exchange” (209). Zoom drew the world into its screen environment by linking collaboration and safety to network capitalism’s need for productivity and efficiency, and its valorization of autonomy and flexibility. The leap into Zoom, and our everyday iterative turn to it, accentuates this link and provokes questions about our constitution as “digital subjects” within social and professional networks that are organized and sustained by technology.[2]

The network model of digital culture invokes a corresponding set of spatial, social, and organizational diagrams that impact how we understand our relation to the world. Terranova argues that “network culture” relies on a gridded or “database” diagram of Internet spatiality where straight lines connect individual points. This rigid binary figuration occludes a more nuanced understanding of network culture as a consolidation of “concepts, techniques and milieus”: “These are concepts that have opened up a specific perception and comprehension of physical and social processes; techniques that have drawn on such concepts to develop a better control and organization of such processes; and milieus that have dynamically complicated the smooth operationality of such techniques” (Terranova, Network Culture 5). Terranova points out that a network is about “an interconnection that is not necessarily technological,” since there “is a tendency of informational flows to spill over from whatever network they are circulating in and hence to escape the narrowness of the channel and to open up to a larger milieu” (2). While it may seem as though “[t]he whole planet feels as if it were compressed into the same virtual space just the other side of a computer screen,” Terranova queries this conceptualization of the Internet as unfolding through a “single plane of communication” (47), pointing instead to the movement of information (back) into specific milieus. She asks: “does an over-reliance on the database model blind us to the more dynamic aspects of the Internet diagram and its relation to network culture as such?” (47).

In its design and implementation, Zoom aggressively reinforces the image of a rational, universal, grid-like space that projects equality and an unchanging order. It funnels communication through a shared, yet singular technological channel that abstracts diverse geographical localities within its generic frames, while cutting off worlds outside its networks. Zoom’s emergence amid a wave of anti-racist protests heightened the sharp division between our inhabitations of globalizing technology and our enactments in specific localities. This division demonstrates what the philosopher Yuk Hui describes as one of the major failures of the twentieth century: the inability to articulate the relation between locality and technology (Hui 62). Even as our most familiar activities — school lessons, family visits, religious ceremonies — migrated onto Zoom, they were reframed within the universalizing grid of a globalized network. Zoom’s ability to capture data from these localized interactions, moreover, reproduces an increasingly individualized digital subject. Hui argues that where a “molar” type of governmentality once initiated techniques to gather information on populations, technologies today make possible a “molecular” surveillance that reproduces the individual with fine-grained data-capture (Hui 61). Zoom captures molecular individual behaviors abstracted from any context and transforms social relations and collaborative exchanges into interactions that can be extracted as discrete commodities.

Within this context, we could consider artistic practices as either corrupted by Zoom or as forces of resistance against its use. But Terranova points out that cultural labor is, from the start, incorporated by networked capitalism, markets, and the technologies that are part of their extension. As she explains, “Incorporation is not about capital descending on authentic culture but a more immanent process of channeling collective labor (even as cultural labor) into monetary flows and its structuration within capitalist business practices” (“Free Labor” 38-39). Crucially, Terranova also points to “capital’s incapacity to absorb the creative powers of labor that it has effectively unleashed” (Network Culture 4). It is precisely this potential excess that contemporary experiments with Zoom “unleash.” They seem to ask: Can Zoom be used in ways not intended? Can creative misuses reveal something of how we are produced and produce ourselves as digital subjects? Can theatre and performances practices devise new concepts, exaggerate, or invent techniques, and bring into the frame the diverse milieus that “complicate the smooth operationality of such techniques”?

Based in Sheffield, UK, Forced Entertainment is a group of six artists (Tim Etchells, Robin Arthur, Richard Lowdon, Claire Marshall, Cathy Naden, and Terry O’Connor), who have been collaborating since 1984 to devise physical theatre and performances. The company develops projects through improvisation and discussion, creating work that introduces “confusion, silence, questions and laughter” and that “needs to be live” (“About Us”). With pandemic restrictions in the UK, Forced Entertainment turned to Zoom to connect to audiences and continue to work, resulting in a three-episode Zoom performance titled End Meeting for All broadcast in April of 2020.

Forced Entertainment is no stranger to using technology. In an essay written in the mid-1990s, Etchells, the group’s artistic director, wrote, [. . .] I like technology (for which we might substitute culture) for how it is used [. . .] [N]ew tech and new culture are never quite used enough — never quite as haunted or resonant as they might be, never quite as ripe for reworking or rewriting” (94). Theatre can call attention to how new technologies “chang[e] everything, from the body up, through thought and outwards. [. . .] Technology will move in and speak through you, like it or not. Best not to ignore” (95-96). This line of thinking provides a context to works such as Nightwalks (1998), which used CD-ROM to create an eerie, interactive cityscape between the real and the cinematic; Quizoola (1996), a durational work of improvised questions and answers, that was remounted and extended into social media spaces in 2013; and Instructions for Forgetting (2001), an exploration of video technology as archive and “occasion for speculation, storytelling, fiction, interpretation” that juxtaposed home movies and videotapes from friends with recordings of world events (“Projects”). But in End, Zoom — and the conditions that made it a necessity — were both medium and subject.

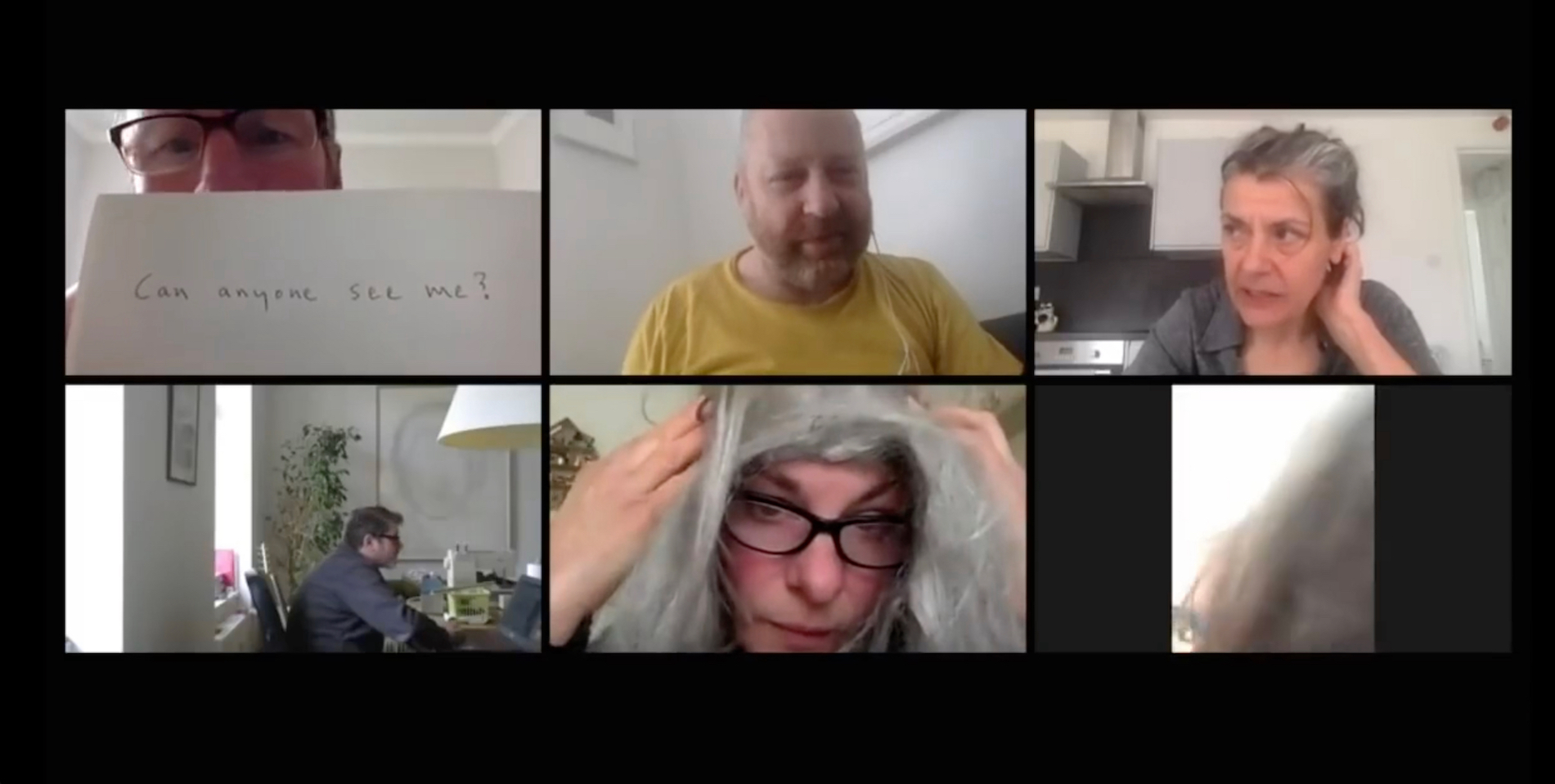

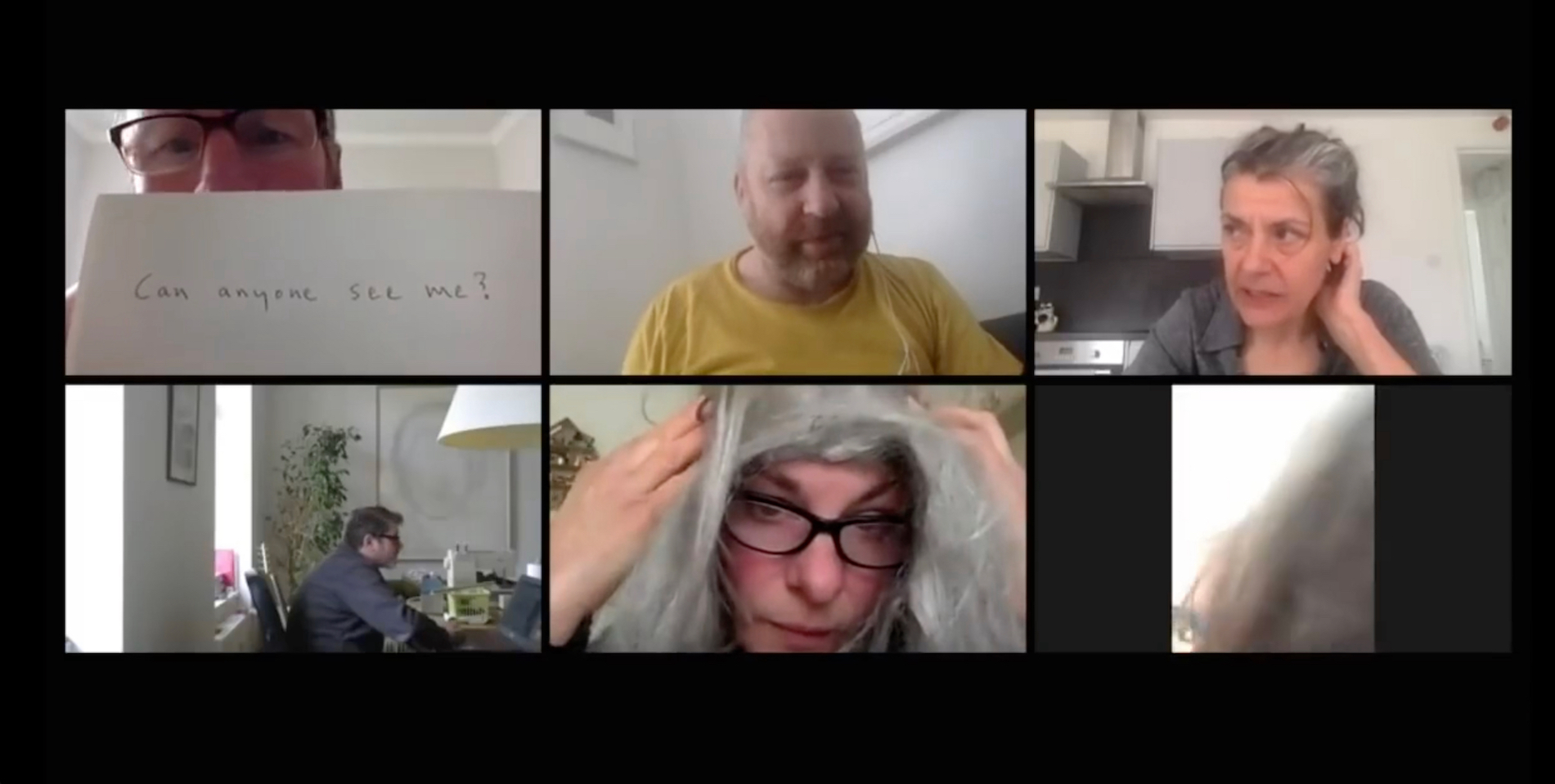

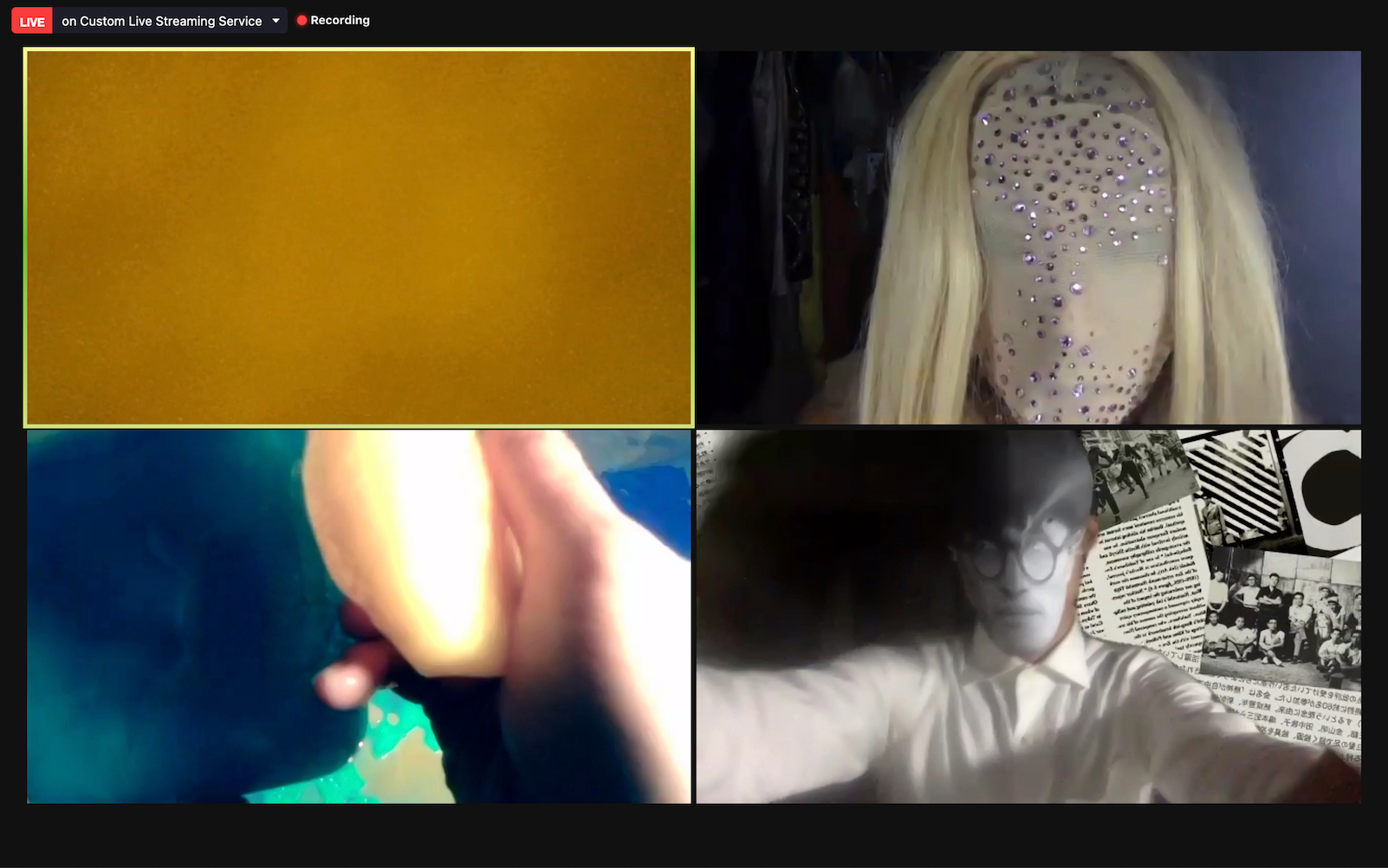

End is composed of three, improvised 20-minute episodes, recorded in a single live take and transmitted via the company’s Vimeo channel. Forced Entertainment’s works are normally several hours in length. End’s shorter format was attuned to, and in some ways dictated by, Zoom’s parameters, and the forms of attention it conditions. To make End, the ensemble met on Zoom from distant locations, including Sheffield, London, and Berlin, collapsing collaborative processes and theatrical frameworks into individual domestic situs. The Zoom screen frames each domestic space, creating a sense of double enclosure — at home and within Zoom — while the windows in the performers’ individual spaces gestured to the worlds (and pandemic) outside. End implies how Zoom transforms the home office into an important cipher of a person’s aesthetic tastes or political leanings, with objects taking part in a larger performance wherein we construct ourselves and are constructed as digital subjects.

End begins by interrupting the linearity of a typical Zoom meeting. Tim, the host, opens by asking the group, “Has it started?” And Claire repeatedly asks, “Can we start again?” This subversion of Zoom’s central aims (to “improve efficiency,” “boost productivity,” and “enhance internal collaboration”) puts the platform’s screen environment at the center of the work. End takes apart this environment in ways that open a discussion about the relation between communication, working together, and the performative nature of affect, online and in theatre.[3] In End, the screen is less a “fourth wall” than a mirror whose opacity is countervailed by its capacity to transmit packets of voice and image. As if to confront this reduction of affect to data, the ensemble amplifies theatrical emotion and artifice: Claire’s wig (“The wig is everything. Everything”), Cathy’s fake tears, and Richard’s skeleton costume theatricalize bodily effects and affective states. The grey color of the wig is a first gesture to the pandemic, signaling that Claire has “been in quarantine for a really, really long time. Like a year. A year and a day.” Other familiar experiences of living through this period on Zoom are introduced and exaggerated as a tangle of missed connections: Richard holds up an envelope with the words, “Can anyone hear me?”; Cathy complains that her screen is freezing; Claire claims she can’t hear Cathy, then responds as though she has.

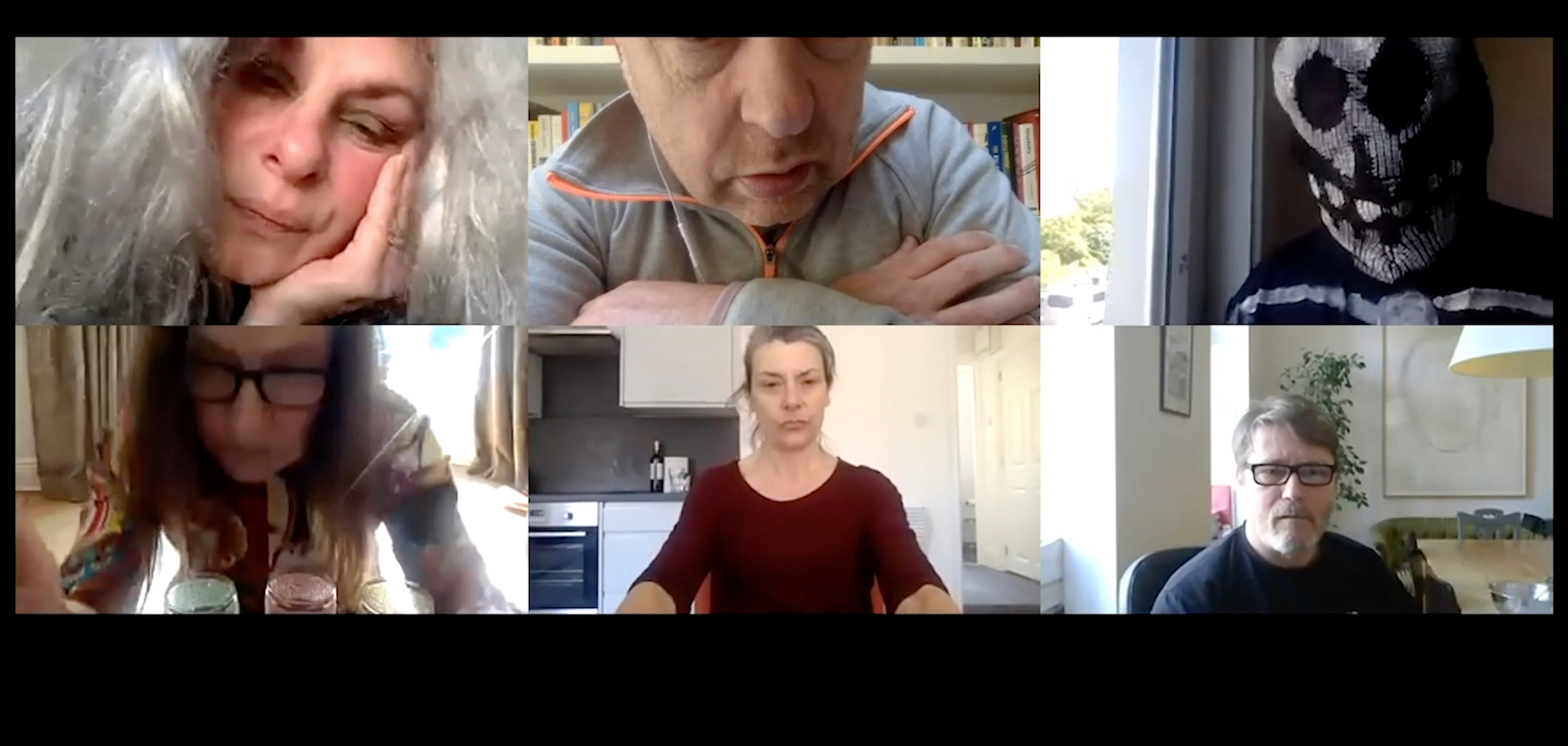

The grid of six screens fragments the “stage” and multiplies sensory demands, making it impossible to keep track: a collage of miscommunication, chaos, and uncertainty. At times, off camera sounds — of birds chirping, dogs barking, violins playing — enter and overlap, as do mysterious voices coming from an actor whose face is turned away from the camera. This subverts the notion that we need to pay attention to one thing or even that we can. End suggests how Zoom batters sensibility and enforces different modes of listening, looking, and speaking. New demands on communication lead to a kind of mute silence where hearing isn’t really listening and speaking doesn’t lead to being heard.

Indeed, learning to talk via Zoom demands a new bodily register of signs to ensure others in the meeting room understand what we are saying. Maaike Bleeker draws attention to how “technology’s materiality [. . .] transforms its users” (Bleeker 39) and requires what she calls a “corporeal literacy” that leads to a “gestural body.” Bleeker suggests how new ways of “handling information and knowledge, of navigating through information by means of gesture [. . .] require us to become more corporeally literate in the sense of becoming more consciously aware of corporeal dimensions of the way in which we read and process information” (43). Digital culture produces a gestural body, in part by linking sensory stimulation with the consumption of information and by transforming touch into the taps, clicks, and swipes that create intimacies between bodies and devices. End amplifies and defamiliarizes the specific sensory environment of Zoom. The performers place their faces up against the screen, their eyes or ears framed within the camera in a kind of haptic listening. Hands or fingers are pressed against the lens, the compressed flesh captured by the camera an indistinct pinkening object obstructing view. Touch is lost on the screen, just as language is garbled, and we “freeze” from the lack of intimacy and understanding. Instead, we work our way through the emotions of collaboration, all the while struggling to comprehend the already complex, sometimes confused codes of human relations.

End is replete with exchanges that refuse to be legible as communicative transactions: gin bottles, badly lit faces, blurry fingers, and darkened spaces overfill the frames. The wigs, make-up, fake tears, and costumes bring backstage rituals to Zoom’s sleek meeting space, messing it up with undisciplined actions and personas at once recognizable and inchoate. The introduction of a passage from Charles Dickens’ Bleak House, read by Tim and recited back by Claire, attempts to anchor character and meaning and communicate a historical parallel to the pandemic. Claire-as-Esther narrates her experience of smallpox, describing how “the usual tenor of my life became like an old remembrance.” She interrupts her recitation to ask, “Can anyone hear me? I feel like I’m just talking, like I could just be saying anything.” Meanwhile, Richard, shirtless in the upper left frame, holds up an envelope that reads “Can anyone see me?” and Cathy asks Claire when she last saw someone. Failed exchanges and the isolation of the pandemic are brought into relation in ways that highlight how the expansion of our communications via Zoom might in fact accentuate the disconnection of bodies, voices, and spaces.

In episode two, Tim faces directly into the screen and types on his keyboard, while Claire asks him if he has gotten what she is saying. The double sense of comprehension and transcription in “getting what I am saying,” speaks to the dislocation of language within the production. Tim’s transcription of Claire’s words also points to Zoom’s own transcription function, which abstracts conversation into searchable, archivable data that at once increases the efficiency of work processes and speeds up tasks that once required human labor.[4]

The final episode closes with Tim describing all the ways in which he thought “it” would be different (“funnier,” “shorter,” “longer”):

I thought it would be more uplifting. [. . .] I thought it would be more about, you know, someone going for a walk late at night on the streets, um, looking up at all the buildings and wondering about the people inside, wondering if they were sick or well or wondering if they were the kind of people who could afford to stay inside or the kind of people who like to work all the time and be in public space or drive things from one place to another.

Tim’s daydream projects to an outside only seen through domestic windows and mediated a second time through the viewer’s screen. Along with this longing is an acknowledgement that being able to stay inside is a luxury not offered to all; that End can take place through Zoom suggests how this new interface has become an ambivalent lifeline. Those workers who “drive things from one place to another” are another. But for them, being amongst others in public spaces is not a choice. Tim’s closing reflection points to the living infrastructures that support those working safely from home, as well as the involvement of both essential and nonessential laborers with the networked applications, positioning systems, and logistical networks that they feed into and depend on. Essential workers are, after all, no less a part of a networked economy.

The poignance of End is in its professed failure to say what it wanted to say. Even more, it suggests the failure of theatre — enclosed in Zoom’s environments and cut off from the social milieu outside — to speak meaningfully to the moment. One by one each member of the ensemble exits their frame. Richard, in his skeleton costume, is the last to leave. The meeting continues, leaving six people-less frames recorded by six individual computer cameras connected to Zoom. This non-ending is perhaps a nod to the durational nature of Forced Entertainment’s productions and to the seeming endlessness of the pandemic. More hauntingly, it points to the digital infrastructures that perform, with or without us.

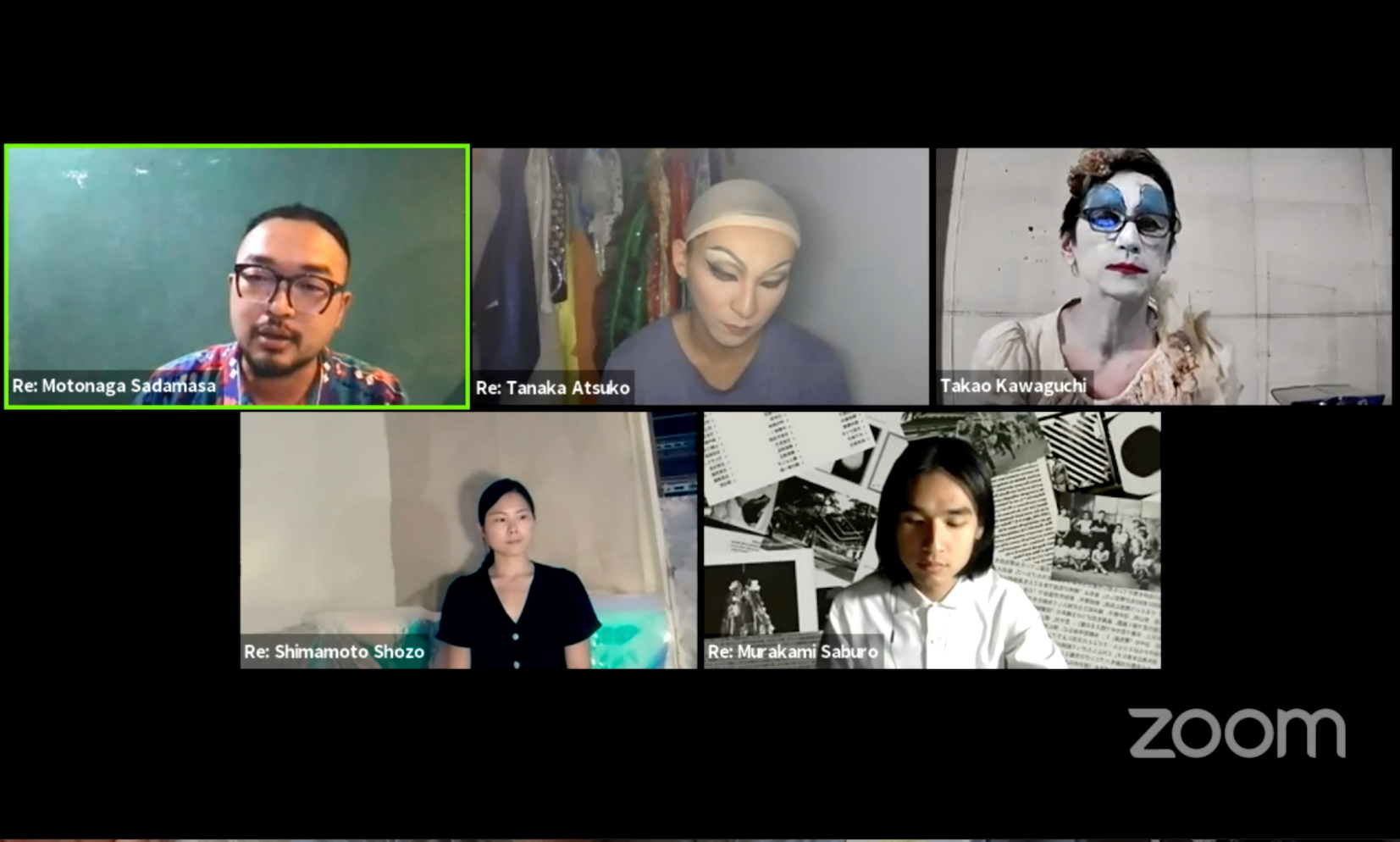

Is this Gutai? is a ninety-minute Zoom performance and lecture curated by Taiwanese artist River Lin and broadcast on May 28, 2021 on the Tokyo Real Underground (TRU) website as part of the Tokyo Tokyo Festival Special 13, “The Future is Art.” Gutai? defies easy categorization: it is part dance party, part drag show, part historical reenactment, and part lecture about Gutai — an experimental artist collective active in postwar Japan. Gutai? also included a conversation between River Lin and TRU’s artistic director Takao Kawaguchi, and video documentation of Dancing with Gutai Art Manifesto 1956, presented in 2020 by C-Lab (Contemporary Culture Lab Taiwan).

Lin works between Taiwan and France and uses reenactment — or what he calls, “replaying” — as a mode of research. Since 2017, he has organized the yearly Asia Discovers Asia Meeting for Contemporary Performance (ADAM) at the Taipei Performing Arts Center. Four ADAM iterations have brought artists and performers from around Asia and the world to Taipei for several weeks each summer. In 2020, Lin moved ADAM on-line in response to Taiwan’s strict travel restrictions. Lin saw this as an opportunity to “think about the internet’s architectural conditions, which are constructed by the livestream setting — the camera and the square-based screen — and how these architectural conditions can generate alternative strategies for artists to perform their body, knowledge, or current existence” (qtd in Bailey 2020). Gutai? continues this line of inquiry by questioning the relation between historiography, technology, and trans-national performance in its re-enactment of works from the Gutai movement.[5]

Gutai prefigures a new materialist focus on “lively matter” and the “vitality of things” (Bennett 112, 63). As stated in the 1956 “Gutai Manifesto”: “Gutai art does not change the material but brings it to life” (qtd in Gutai?). Replaying this history on Zoom, Gutai? can also be seen as an example of New Media Dramaturgy (NMD), an approach that deploys an “aesthetic flat ontology” and “mobilises collaborations between artists and things” (Eckersall et al 4). NMD proceeds “with the understanding that the body/technology nexus in performance functions to amplify rather than negate bodily and affective experience” (4), wherein “bodily sensations and sense experiences are now redistributed through technical means rather than diminished or deemphasised” (2). Understanding Gutai? in this way prompts questions about how Zoom channels and captures these sensations and experiences and how Gutai? works against the stabilization of subjectivity enforced by the platform. In his replaying of Gutai history, Lin channels the energies of the past to wonder how postwar Gutai artists would respond to twenty-first-century live-streaming technologies.

Where Zoom prompts regimented participation and curated self-presentations, Gutai? is emphatically playful in its jostling of theatrically constructed personas that saturate the grid and exceed the limits of the frame. Lin and his cast — who identify as artists, performers, and drag queens — recall Forced Entertainment’s improvisations when they slip in and out of the frame, put on and take off make-up. Each Zoom window in Gutai? is labeled with the name of an iconic Gutai figure; it is never quite clear whether, or when, Lin’s performers are playing a role or playing themselves — or both at once. As in End Meeting for All, we are never quite sure where the performance stops and the “real” communication starts, or where the role ends and the “real” person begins.

In the five-minute performance that bookends Gutai? flashy colors and flickering lights recall early music videos, though here collaged into Zoom’s fixed frames. The soundtrack is a remix of Yoko Ono’s Yang Yang (1973). In three of the four frames, Lin’s collaborators replay a specific work from Gutai, bringing it into a contemporary screen environment. Chien Shih-han emerges from behind two white strips that we later recognize as fluorescent bulbs referencing Tanaka Atsuko’s Electric Dress (1956). Eric Tsai disappears and reappears in the screen (a function of Zoom’s virtual background setting which swallows the human figure when a person moves too far or close to the camera) and pulls at transparent plastic wrap. Tsai (as the Gutai artist Murakami Saburo) replays Passing Through (1956), where Murakami ran through 42 panels of framed paper. Chang Yun-Chen describes how she is interested in the destructive actions that were part of Gutai artist, Shozo Shimamoto’s art-making process. All three performers use technology as a way of questioning. They revisit history and reroute the networks through which it travels. Chang’s use of close-ups of her material, Tsai’s flickering appearance, and Chien’s introduction of bulbs, material, and costume treat Zoom not as a technological “tool” with a pre-given set of relations, but rather as an extended environment of their own re-making.

After the performance, Lin opens his lecture by welcoming viewers from “different parts of the world.” This presumed transnational audience remains invisible to the performers and to itself, along with the specific local conditions of confinement, suffering, or loss viewers may be living through. As a performance environment, Zoom leaves out as much as it brings in, disconnects as much as it connects. The promise of connecting coincides with a simultaneous effacement of the multiplicities of localities that comprise “the global.” Although inevitably the effects, and affects, of any performance will spill back into the milieus of its audiences and the performers themselves, Zoom maintains an illusion of a generic space that seamlessly connects a context-less grid of faces, bodies, sensations, and environments.

The transnationally networked ambition of the evening’s broadcast contrasts with Gutai’s experimentations, which were largely unknown outside of Japan. Lin shows a timeline of the New York art scene — including Allan Kaprow’s “Happenings,” John Cage’s chance experiments and the Fluxus movement — alongside contemporaneous Gutai events. This juxtaposition complicates Western narratives of modernist experimentation. Moreover, by overlaying historical images, people, and events of Gutai with live performances, personas, and conversation, and placing both within Zoom’s presumably universal space, Gutai? retells a history of postwar Japan that challenges ossified narratives — of nationhood, of the modern — and at the same time, undermines the stabilization of subjectivity enforced by Zoom’s scripted protocols for presentation and interaction.

Gutai? seems one response to Benjamin Haber and Daniel Sanders’ call for a “world-building vision for the politics of digitality” that foregrounds queer and feminist experimentation with digital space. They argue that “queer theory and performance studies offer a perhaps uniquely useful framework for encountering the digital, as these fields have long been focused on the contingency of identity, embodiment, and the social.” Likewise, they add, “Digital power and practice, too, offer lessons for queerness, highlighting the marketability of difference and queer cultural forms and the limits of a politics centered on normativity” (Haber and Sanders). Gutai? brings into Zoom’s homogenous, “global” screen environment the diverse “queer sites” (Ramos and Mowlabocus) within which queer subjectivities are constituted. In his conversation with Takao Kawaguchi, Lin (as Motonaga Sadamasa) describes Gutai as a practice of “queering what has been concrete, what has been fixed, what has been written.” He reframes postwar Gutai as a movement of artists who used performance to transform “heteronormative ways of making art.” Lin speaks specifically of a “Taiwanese queerness in the expanded context of Asia” and views his own “queer practice” not as a theory or “approach,” but as an extension of the expanding practices of Taiwan’s democracy.[6] Gutai? thus challenges Zoom’s normalizing environment to suggest there is room within its frames, functions, and networks for diverse localities, where queerness comes into contact and conflict with specific histories and political, cultural, and religious practices.

Gutai? interrupts the binary character of digital culture to produce not only a queer space of ambiguous bodies but also a flattened ontology where human bodies, objects, and affects take on equal value as performative objects. While the work is nevertheless captured as a product of globalized cultural production, the performers do not simply accept Zoom as a neutral technology of mediation. Instead, they queer Zoom’s screen environment, unleashing a multiplicity of subjectivities that resist capture and abstraction. Both End and Gutai exaggerate the distance between the digital subject as “an abstracted position, a performance” that is constructed “from data, profiles, and other records and aggregates” (Goriunova 126) and the lived subjectivities that precede and are entangled with this persona. In this way, these experiments complicate the translation of living persons into individualized packets of banalized coherence.

Where once mediating technologies captured immaterial labor’s capacity to generate a social relationship, and it was enough to transform the laboring body into the singular artist (as in Walking) or a de-personalized figure (as in Quad), today what is enclosed and sought through capture is subjectivity itself and the sets of relations, interactions, and affective responses that comprise it. Whereas the demand for immaterial, creative labor has always depended on the exploitation and exhaustion of the affective bonds that link performers to each other, to the production, and to the audience, what Zoom encloses and abstracts into its globalized networks is the production of those very bonds. End and Gutai? seem to recognize this shift and find ways to perform in and collaborate with Zoom, while thwarting its enforced efficiencies, abstracted subjects, and seemingly fixed enclosures.

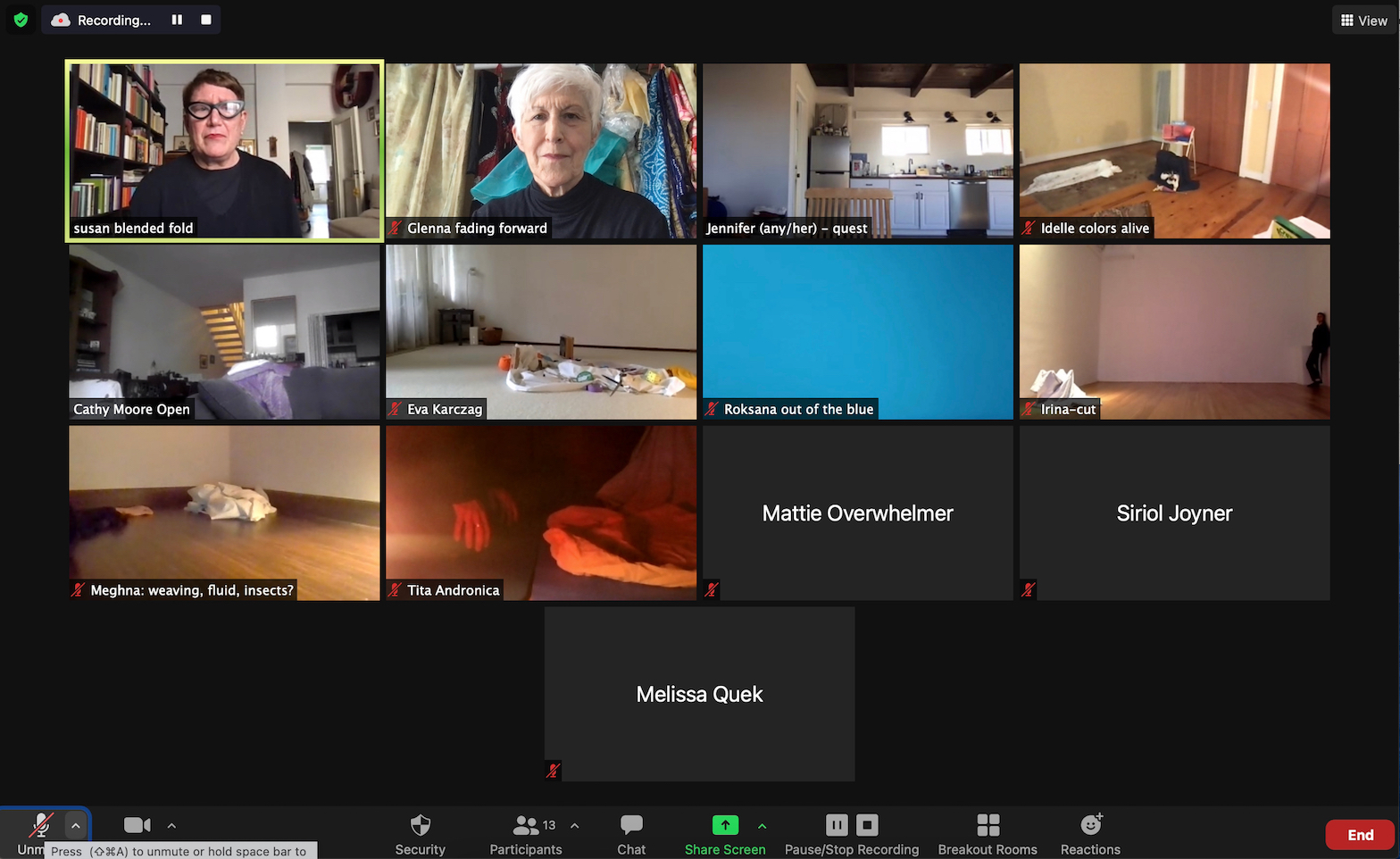

In a final example, we consider the pedagogic practice of Glenna Batson and Susan Sentler. In their collaborative workshops, Batson and Sentler draw on Deleuze’s articulation of the fold as an interweaving of materiality, wherein space, time, and movement are coiled and compressed and the world is conceived as a body of infinite enfoldings.[7] While Deleuze’s treatise is expressed through Leibniz’s monadology and the Baroque, Batson and Sentler, both dance practitioners by training, explore folding on a somatic and experiential plane. Participants in their workshops come from multiple disciplines. They join the workshops to explore an aesthetic playground of expanded modalities and enfolded materialities and to loosen default modes of working, making, and performance. Both Batson and Sentler were keen to keep their decade-long practice going during the pandemic but were hesitant to work online. The F/OL\D depended on working in proximity, with close observation, touch, and embodied exchange. Online formats seemed to offer little possibility for the infrastructure of care needed for this shared practice. However, as classes, webinars, and talks moved online, their experiences with these new formats opened them to the materiality of Zoom’s spaces and their potential for refiguration.

This refiguration begins by expanding the audio-visual field and easing the rigidity of Zoom’s grid. The screen itself is refigured as a shared studio. At the start of each class, participants are invited to orient their gaze and body away from the screen, then guided to dive inwards by closing their eyes or expanding their peripheral vision. Turning away, tuning in, and opening the gaze all challenge the habituated modes of apperception prompted by Zoom. Along with these sensory experiments, the inclusion of participants’ environments — both their physical sites and inner bodily landscapes — become central to the process. Participants are prompted to sculpt and curate their physical space and find objects, props, or texts that might act as sensorial tethers. The grid of frames is thus reconfigured as a theatrical collage of interconnected object-bodyscapes, similar to End and Gutai? These experiments with body, space, and material stretch the confines of Zoom’s audio-visual environment. At other times, the Zoom window is de-prioritized, and participants are encouraged to work and listen in ways that suit their needs; they can turn their cameras or microphones off and work in or outside the frame. At any time during the workshop, the grid of participants may include empty spaces, darkened windows, or the framed view of someone working on their own. Participants are also encouraged to change their names, suggesting a form of role-play not unlike End and Gutai?[8]

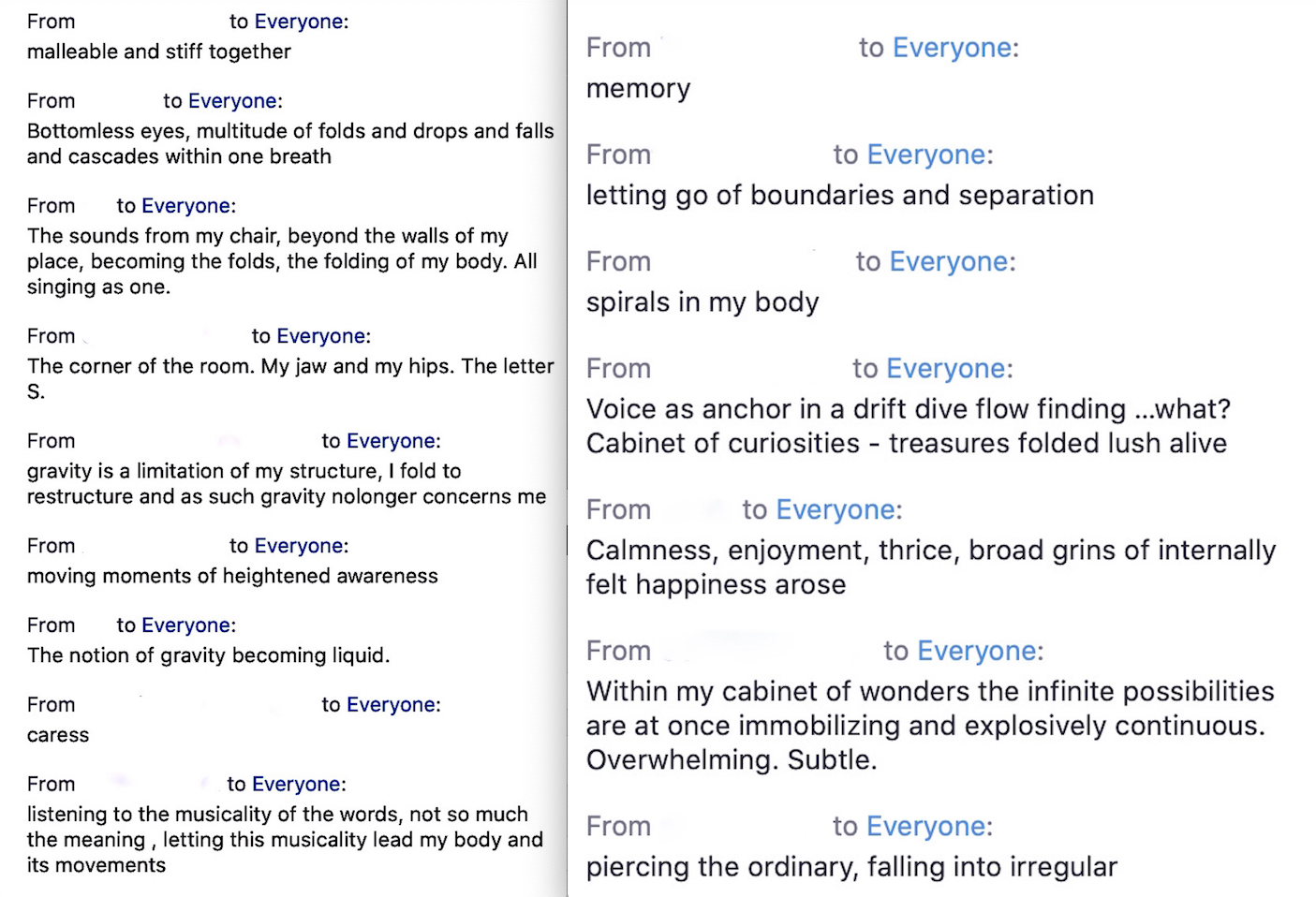

Unlike a typical Zoom meeting, the workshop supports different configurations and durations of participation. Short improvisational dialogues take on a kinetic value, with multiple tones and rhythms emerging as a material. Moments of automatic writing, drawing, or making lead to periods of “harvesting,” where participants hone their explorations. “Scripts” hold participants in their exploratory “dives,” evolving through the facilitators’ continuous “languaging,” but also via notes passed back and forth using Zoom’s chat function. The chat is not only a site to pose questions and comments, but a place to generate the words necessary to the process. A to-and-fro of reflection produces a poetic amalgam of vocabulary that resists ascription as indexical content. The work is composed as a continuous co-creation, a “feed-forward mechanism for lines of creative process” that yields what Erin Manning defines as an “anarchive,” — “a repertory of traces of collaborative research-creation events” (“Anarchive”).

Longer activities include presentations on a theme or theory, more intense improvisational dives, or a devised work that, interspersed with pause and rest, creates a pace unique to each class. These diverse experiments acknowledge the different backgrounds of the participants and encourage a free-ranging exploration of ways of making and sharing work. Batson and Sentler loosen the hierarchical relation between “host” and “guest” by encouraging participants to choose how they contribute throughout, and thus distributing attention and expanding agency within the workshop, as participants are encouraged to jump in and out of breakout rooms. This capacity to choose how one contributes works to distribute attention and expand the participants’ agency within the workshop. As they come together and drift apart, the regulated interactions of a global workroom are displaced by an encountering of multiple and synchronous lived experiences and spatialities, all inhabiting the gridded network not simply to remain productive, but to articulate the distance between the “living self” and the digital subject, as a “non-empty, qualitative” space, or movement, that “can expand and contract, stretch and collapse” (Goriunova 129).

Virtual spaces and video technologies have become inextricably part of how we work, relate to others, and perform ourselves. We can quickly learn to see only what is inside the frame and to respond to the prompts and protocols of these technologies, perhaps especially when our lives seem to depend on it. The challenge will be to resist the safety of Zoom’s enclosures, along with the instrumentalized behavior and individuated selves they condition. Performance experiments on Zoom raise questions about how we inhabit these technologies, and how they inhabit us. There might be, post-pandemic, a refocused attention to the specific localities of performance. We might return to theatres with renewed appreciation for its visible seams, obviously constructed personas, and particular “brand of stage management,” that, as Shannon Jackson puts it, invites us to “think deliberately but also speculatively about what it means to sustain human collaboration spatially and temporally” (Jackson 14). Likewise, we might be more attentive to how our collaborations with technologies create ever-more productive subjectivities interacting within increasingly differentiated networks. Theatre and performance can counter the reduction of informational flows to ever-narrower channels and show us how Zoom, like any new technology, “is rewriting bodies, changing our understandings of narratives and places, changing our relationships to culture” (Etchells 97). If the performing arts can be called “essential” in any way, it is perhaps for the way they can register these changes, practice hybrid forms of embodiment, and counter the abstraction of selves and worlds within the networks that contain, constrain, and sustain us.

“The particularity of the commodity produced through immaterial labor… consists in the fact that it is not destroyed in the act of consumption, but rather it enlarges, transforms and creates the ‘ideological’ and cultural environment of the consumer” (Lazzarato 137). ↑

As Olga Goriunova defines it, “The digital subject is an abstracted position, a performance, constructed persona from data, profiles, and other records and aggregates [. . .]. A digital subject comes after the [living] subject, requiring new ways to understand how it connects to the subjectivities of living persons” (126). ↑

As director Anne Bogart points out, affect in theatre is a technical feat that involves “very precise work on form, psychology and timing” (xi). When an audience is feeling a moment onstage, the actors are not sharing in this moment of empathetic communion, but are instead “busy, engaged in setting up the necessary conditions for the audience to respond” (x). Zoom almost inevitably disrupts both “time” and “timing” because it separates voice and image into different packets, and privileges voice. This, in turn, complicates the “synchrony” that humans depend on to read between gesture, voice and expression, leading to “Zoom fatigue” (Ferng 208). ↑

While the capture of language as data is not new, Zoom is perhaps the first widely available (“free”) service that makes explicit the ways in which all manners of communications are being recorded and captured as discrete packets of information and offered up as a service. Zoom’s “free” plan limits the length of calls and number of participants, while requiring users grant access to the anonymized data that is created when we use it. As with other social media, we pay to use these free platforms with this intimate access to our abstracted lives. ↑

The artists include River Lin (as Motonaga Sadamasa); Chien Shih-Han (as Tanaka Atsuko); Chang Yun-Chen (as Shozo Shimamoto); Eric Tsai (as Murakami Saburo); and Takao Kawaguchi (in semi-drag). ↑

Two important studies that speak to the intersection between queerness, globalization, and technology are Frédéric Martel’s Global Gay: How Gay Culture Is Changing the World (MIT Press, 2018) and Regner Ramos and Sharif Mowlabocus’s edited collection, Queer Sites in Global Contexts: Technologies, Spaces, and Otherness (Routledge, 2021). Lin’s FW: Wall-Floor-Window Positions can also be read as a queering of the white, male, heteronormative body and a probing of the “queer homophobia” that runs through Nauman’s practice (Bryan-Wilson 2019). ↑

“The unit of matter, the smallest element of the labyrinth, is the fold, not the point, which is never a part, but only the extremity of the line” (Deleuze 231). ↑

This “renaming” was a suggestion from dance artist and educator Peter Mills who uses this tool within his “questioning practice” (see Mill). ↑

“About Us.” Forced Entertainment, www.forcedentertainment.com/about/. Accessed 13 January 2021.

“Anarchive – Concise Definition.” SenseLab 3e. https://senselab.ca/wp2/immediations/anarchiving/anarchive-concise-definition/. Accessed 13 January 2021.

Batson, Glenna, and Susan Sentler. Human Origami. humanorigami.com.

Beckett, Samuel. Collected Shorter Plays. Faber, 1984.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: The Political Ecology of Things. Duke UP, 2010.

Bogart, Anne. “Forward.” Theatre and Feeling. Red Globe Books, 2010, pp. ix-iv.

Bailey, Stephanie. “River Lin: Workshopping Performance.” Ocula. August 31, 2020. https://ocula.com/magazine/conversations/river-lin-workshopping-performance/ Accessed 11 June 2021.

Bryan-Wilson, Julia. “Bruce Nauman: queer homophobia.” Burlington Contemporary Journal May 2019. https://doi.org/10.31452/bcj1.nauman.bryan-wilson. Accessed 11 June 2021.

Eckersall, Peter, Helena Grehan, and Edward Sheer. New Media Dramaturgy: Performance Media and New-Materialism. Palgrave, 2017.

End Meeting for All. Performed by Forced Entertainment. Co-produced by HAU Hebbel am Ufer (Berlin), Künstlerhaus Mousonturm (Frankfurt a.M.), PACT Zollverein (Essen). Live streamed on Zoom, April 2020.

Etchells, Tim. Certain Fragments: Contemporary Performance and Forced Entertainment Psychology Press, 1999.

Ferng, Jennifer. “Post-Zoom: Screen Environments and the Human/Machine Interface.” Architectural Theory Review. Vol. 24, no. 2, 2020, 207-210.

Fiala, Freda. “Windows into Performance Art: River Lin’s Artistic and Curatorial Practices.” The Theatre Times. February 28, 2021. https://thetheatretimes.com/windows-into-performance-art-river-lins-artistic-and-curatorial-practices/. Accessed 3 June 2021.

Goriunova, Olga. “The Digital Subject: People as Data as Persons.” Theory, Culture & Society. Vol. 36, no. 6, 2019, pp. 125-145.

Haber, Benjamin, and Daniel Sander. “Introduction to Queer Circuits: Critical Performance and Digital Praxis.” Women and Performance. Vol. 28, no. 2, 2018, n.p. https://womenandperformance.org/bonus-articles-1/benjamin-haber-daniel-sander-28-2. Accessed 10 June 2021.

Hui, Yuk. “Machine and Ecology.” Angelaki. Vol. 25, no. 4, 2020, pp. 54-66.

Jackson, Shannon. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. Routledge, 2011.

Lazzarato, Maurizio. “Immaterial Labor.” In Radical thought in Italy: A potential politics. Eds. P. Virno and M. Hardt. U of Minnesota P, 1996. pp. 133-147.

Martel, Frédéric. Global Gay: How Gay Culture Is Changing the World. Trans. Patsy Baudoin. MIT Press, 2018.

Mill, Peter. Artist website. stillpeter.com Accessed 13 January 2021.

Ramos, Regner and Sharif Mowlabocus, eds. Queer Sites in Global Contexts: Technologies Spaces, and Otherness. Routledge, 2021.

Terranova, Tiziana. “Free Labor: Producing Culture for the Digital Economy.” Social Text. Vol. 18, no. 2, 2000, pp. 33-58.

———. Network Culture: Politics for the information age. Pluto Press, 2004.

Villasenor, John. “Zoom is now critical infrastructure. That’s a concern.” Brookings. 27 August 2020. https://brookings.edu/blog/techtank/2020/08/27/zoom-is-now-critical-infrastructure-thats-a-concern/. Accessed 21 January 2021.

Zoom homepage. Zoom Video Communications. Inc. 2021. https://zoom.us.