In 2008, following a complaint from a high-profile children’s protection advocate, New South Wales police seized twenty artworks from the Roslyn Oxley9 gallery in Sydney prior to the opening of an exhibition by celebrated Australian photographer Bill Henson. Henson, who exhibited at the 2005 Venice Biennale, was showing a series of new untitled images and, following this raid, the NSW Department of Public Prosecutions launched an investigation into allegations of child pornography and considered laying obscenity charges against the photographer. The works in question were part of Henson’s ongoing investigation into the liminal state of childhood and adolescence, and, as the artist argued at the time, were part of the Western tradition of nudes. Further adding to the public concern was then Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s denouncement of the work as “disgusting” and, in response to the narratives of sexuality that the work explored, Rudd publicly stated he believed we should “just let kids, be kids” (Westwood).[1]

There are many ways of framing this moment in Australian art history, and there are questions of authorship, morality, censorship, and free speech, which all emerge in an interrogation of why this occurred and how it played out in the public arena. There are also many ways to critically and ethically engage with Henson’s complex and beautiful works depicting adolescence. From my perspective as a theatre practitioner who makes contemporary performance work with and for children and young people[2] (at the time of the controversy I was the Artistic Director and Chief Executive Officer of one of Australia’s largest government-funded youth theatre companies), it became a watershed moment in my practice. I was particularly struck by Rudd’s statement, “just let kids, be kids,” and the kind of overwhelming popular support this notion seemed to have.[3] What were the discourses shaping and defining these understandings of childhood that Rudd was referring to? Who was responsible for creating, circulating, and maintaining these ideas? And crucially, for the work I was interested in creating, where was the voice of children in this debate, and what agency did they have in addressing these views of them? During the Henson affair, children were never publicly asked for their opinion on the work, and it seemed this work was popularly understood as only relevant and suitable for adult audiences. As Australian social theorist Joanne Faulkner has argued, and as Rudd’s statement demonstrates, there is a tendency in Western culture to reduce childhood to an idyllic innocence, which reduces children’s interests to being “in need of protection” and ultimately serves to fetishise their vulnerability (Faulkner 10). In her book The Importance of Being Innocent: Why We Worry About Children (2010), Faulkner argues that our focus on children’s vulnerability is a direct result of our “rigid understanding of childhood as unworldly, incapable and pure” (Faulkner 11). Adult-child relations are predicated on this political construct of childhood and children as vulnerable; Henson’s work simultaneously disrupts and plays on this dominant idea. Further, the artist’s work also complicates notions of the cultural agency of children and young people by distorting our understandings of who is responsible for controlling the gaze, while raising questions about how these photographs have been created.

As a theatre-maker who works with children and young people in a range of contexts (including schools and community, Youth Arts organisations, mainstream theatre programs, and independent theatre productions), I am acutely aware of the responsibility of constructing the frame within which the young people are viewed. At times, I have seen contemporary performance work featuring children where I, too, have felt confronted and thought that the ethics of creation, and of production, were questionable. Henson’s works and my experiences over the last decade seeing and making work for adult audiences that features children onstage raise the very questions central to this article: can children function as political symbols in art? How do we ensure that the process of creation and framing of work involving children adheres to careful ethical considerations? What might a creative practice involve if it were to recognise children’s cultural and creative agency and be underpinned by ethical principles of collaboration? How might creative practitioners promote children’s contribution to decision-making and agency, and what are the pathways to ethical participation? How do we create a platform for children’s voices and consider the rights of children to contribute to discourse on matters that affect them?

To approach these complex questions, it has been useful to start articulating my own practice in terms of current methodological thinking in social research with children. My practice (and research) is informed by sociology, legal studies, childhood studies and education discourses, drawing on understandings of childhood as a social construction and children as competent social agents with the rights and capacities to participate in society (Loreman 18; van de Water 110). Over the last decade of practice in this field, I have noted an increase in organisations wanting to work or engage with children. I attribute this trend to part of a global shift toward recognising the evolving capacity, agency, and expertise of children within the institutional realm (Bradbury-Jones and Taylor 161). My experience with organisations seeking children’s participation is that too often the expectation of the child’s contribution is to resemble that of adults. My colleague, and acclaimed Australian Youth Arts practitioner, Alex Walker,[4] argues that what the child offers in terms of critical interrogation of dominant ideas is compelling: they can provide a radical perspective on contemporary discourses though their innate curiosity, risk-taking, and lateral and imaginative problem-solving — all qualities associated with notions of elasticity and disruption (Walker). Walker argues that children have a capacity to hold at once a plurality of ideas, but that this does not dilute their dedication to a concept (Walker). However, to adequately value these traits and their capacity for change and impact requires a subversion of the idea that the adult human is ‘boss’ as well as a willingness from adults to concede modes of power and to embrace new models of participation and inclusion.

This subversion of the adult-child relationship requires an elastic approach to the social contract. Here, I take the term elastic as a useful way of naming and reflecting on the ongoing negotiation between adult artist practitioner and child collaborator. This negotiation involves an elastic and responsive expansion and contraction of how adult authority is working in the relationship, and a willingness on behalf of the adult to subvert who wields the power. Walker equates this subversion of the adult-child social code to the kind of rethinking it might take to value not only the creative product but also the creative process. “We may seek creative outcome and output, but the creative process is another thing entirely. It’s messy, not just physically messy, but it’s not linear. It looks like messy thinking, a waste of time, a lot of failure, inefficiency. These are things that are incongruous with business models and the systems that organisations use to arrive at success” (Walker). What Walker is suggesting here is that to learn from young people and children requires an uncomfortable shift. It means valuing novel approaches that may look and feel ‘silly’ or ‘messy’ or even ‘naughty’ and understanding children beyond the epistemological limits of ‘development.’ It means shifting the existing spatio-temporalities of adult daily life, which precludes time to imagine other possibilities. It means finding ways to not deny adults moments of the free play that children are much more likely to have daily access to. Philosopher David Harvey refers to these moments of free play as “fertile ways of exploring and expressing a vast range of ideas, of taking on sedimented hierarchies and societal practices and imagining new possibilities” (Harvey 19). Unstructured time, unstructured thinking, and free play are qualities more commonly associated with childhood and characteristic of elasticity. They are also qualities that artists, businesses, educational institutions, and creative sector organisations are actively seeking as they examine possible futures and new imaginings to face the challenges ahead. As four recent child collaborators who worked with me and Alex Walker articulated in their keynote speech at the Creative State Summit,[5] “When we work with Alex and Sarah, they let us speak. The scripts are made up of things that we have actually said, not rubbish junk that we don’t mean. They listen to our ideas. They let us be free. When we work with Sarah and Alex we work quickly and intelligently” (Bianka et al.). It’s important that the inclusion of young people is underpinned by an approach that addresses adult-centric ideas of how and when children should creatively contribute and what that contribution might look like. In my work with children and young people, I advocate strongly that there must be a shared view amongst the adults asking children to participate in their organisational culture (or indeed in their creative endeavours) that understands children as experts of their own experience. This includes a shared acknowledgement amongst adults that children are not “future people”; they are indeed people right now. This philosophy echoes that of the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, responsible for the Children’s Rights Charter. They state, “A shift away from traditional beliefs that regard early childhood mainly as a period for the socialisation of the immature human being towards a mature adult status is required. The Convention requires that children, including the very youngest children, be respected as persons in their own right” (UNCRC 3). The paradigm of children’s vulnerability and their need for protection played a critical role in motivating the adoption of the UN Convention in 1989. The Convention itself goes into some detail about the vulnerable status of children and their need for safeguard and special care (Tobin 156). Importantly, however, the charter confirms the evolving capacity and resilience of children, asserting their rights as cultural citizens and for freedom of cultural expression and thought. The charter is also the basis for child-centred pedagogical approaches to practice in the arts, and for the evolving thinking in the Youth Arts and Theatre for Young Audiences sector in Australia in relation to children and their cultural, civic, and political agency (Snyder-Young; Giles). Childhood studies scholars have suggested that the child as a discrete category is disappearing as “representations of children move from simple to sophisticated and reflect the acknowledgment in international law that children are not merely becomings but beings” (Tobin 157). Legal scholar and children’s rights specialist John Tobin posits that the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child offers a more comprehensive conception of childhood and demands a transformation in the way that children are viewed (160). Tobin argues that the rights-based approach to conceptualising children and their evolving capacity is not necessarily a common or dominant approach in contemporary Western society, but adults’ complicity in constructing children’s vulnerabilities is being questioned within legal, education, medical, and health frameworks (182). This presents a challenge to historic perspectives of childhood as a state of development, instead positioning children as entities in their own right.

The positioning of children and childhood as historical, social, and political constructions, disconnected from ideas of cultural and civic agency, is demonstrated clearly by the recent public commentary — driven by adults — around children ‘striking’ around the world and leaving school to join marches in support of action on climate change. In 2018 and 2019, inspired by sixteen-year-old climate activist Greta Thunberg from Sweden, students from across Australia and the world have repeatedly turned out in their thousands to urge governments to make climate change an urgent issue, while calling for a range of policy measures, including requesting that Australia meet the Paris Agreement emissions targets. This act of political engagement elicited highly contrasting opinions in the public and political arena. There were those who were delighted that young people could be so passionate about matters of public policy and saw great hopes for the future. There were also those who believed, including Australian Federal Education Minister Dan Tehan, that children were being used as puppets of the extreme left of politics and argued that if “they are not entitled to vote, they are not entitled to strike” (“Education Minister Dan Tehan”) . The Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, made this statement in Parliament when urging children not to attend the strikes and miss half a day or a day of school: “We don’t support our schools being turned into parliaments. What we want is more learning in schools and less activism in schools” (“Climate change strikes”).

What the ‘climate strikes’ clearly illustrate is that the idea of children as rights-bearers, as individuals with entitlement to civic and cultural agency, is still decidedly challenging to adult-centric institutions. There was little to no public commentary around the idea not only that children were entitled to be heard and listened to on matters that affect them — in this case, the very serious issue of climate change policy — but also that these are rights enshrined in an international legal document that Australia, and many other countries across the world, are a signatory to. It is possible to conclude that despite Australia’s endorsement of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, the dominant attitudes toward children seem to indicate that adults believe children are limited in terms of their capacity to contribute to public discourse, politics and policy, and other civic concerns (Senior 72).

My practice-based research foregrounds a rights-based approach, which draws on the frameworks of Youth Arts and inclusive arts. Combined, these frameworks of creative practice establish a working methodology for collaborating with children that embraces elasticity as a central tenet of the creative process. To collaborate in this way with children requires practitioners to iteratively expand and contract their thinking, to work fluidly and spontaneously, as what is required creatively emerges in a non-linear, intuitive way. This approach also acts as an effective resistance measure against the ostensible attitude about children in the public response to the climate strikes, which I argue points to a wider attitude about children rather than a response to a specific event. The salient features of a rights-based approach respond directly to a number of articles within the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, including but not limited to:

and

Drawing on these obligations as framing statements for the intentions of collaborative creative practice, I developed three key constituent features of a rights-based framework for working with children in performance:

These creative methods are designed to create equitable and accessible ways of collaborating with diverse groups of children and young people and include creative approaches to story-sharing, non-verbal, visual, and kinaesthetic approaches to developing creative material and play-based enquiries, as well as other generative tasks as part of the creative process.

This includes strategies for creating brave, safe, and inclusive spaces for rehearsal and performance, and strategies for diffusing knowledge amongst all collaborators. Importantly, it requires commitment from adult collaborators to cede power where possible and resist the expert–amateur dichotomy inherent in adult–child social relations.

Adult collaborators must be committed to practices that comprehend children’s rights and respect and take seriously the information children impart. Further, child-led dramaturgies may be in opposition to the adult-constructed values and views of what constitutes critically successful performance. These new forms must be embraced as part of a rights-based approach. The creative strategies must focus on children’s strengths and capacities rather than their perceived deficits or vulnerabilities and, in doing so, provide a platform for the (sometimes disruptive) insertion of children’s ideas, opinions, views, and visions into a range of contexts. This shifting in what is valued and given primacy in a creative collaboration reflects the productive features of elasticity. Practitioners implementing a rights-based approach to working with children and young people not only alter their understanding of the strengths of children and young people but must be prepared to work with elasticity as a core part of their thinking, so that they might respond to creative possibilities as they occur and be prepared to shift course at any time.

In the following section, I will use the case study of a project I directed in 2019, where I applied ideas of the rights-based approach to test their efficacy. For the purposes of this article, I have chosen to analyse key aspects of what was required to enable and foster a rights-based approach and how elasticity features as a central concern of the creative collaboration.

The Cabin!

The concept, script, and story for The Cabin! was developed over a two-year period. Lead artist Joseph O’Farrell (hereafter known as JOF) worked with primary school students, aged between six and twelve years, across the UK and Australia at both in-school and arts-centre supported workshops. Sometimes the workshops ran for one day, and other times they were week-long intensives with the same group of child collaborators. In this way, a script emerged for The Cabin!, sculpted and formed by JOF through this series of interactions with and contributions from children.

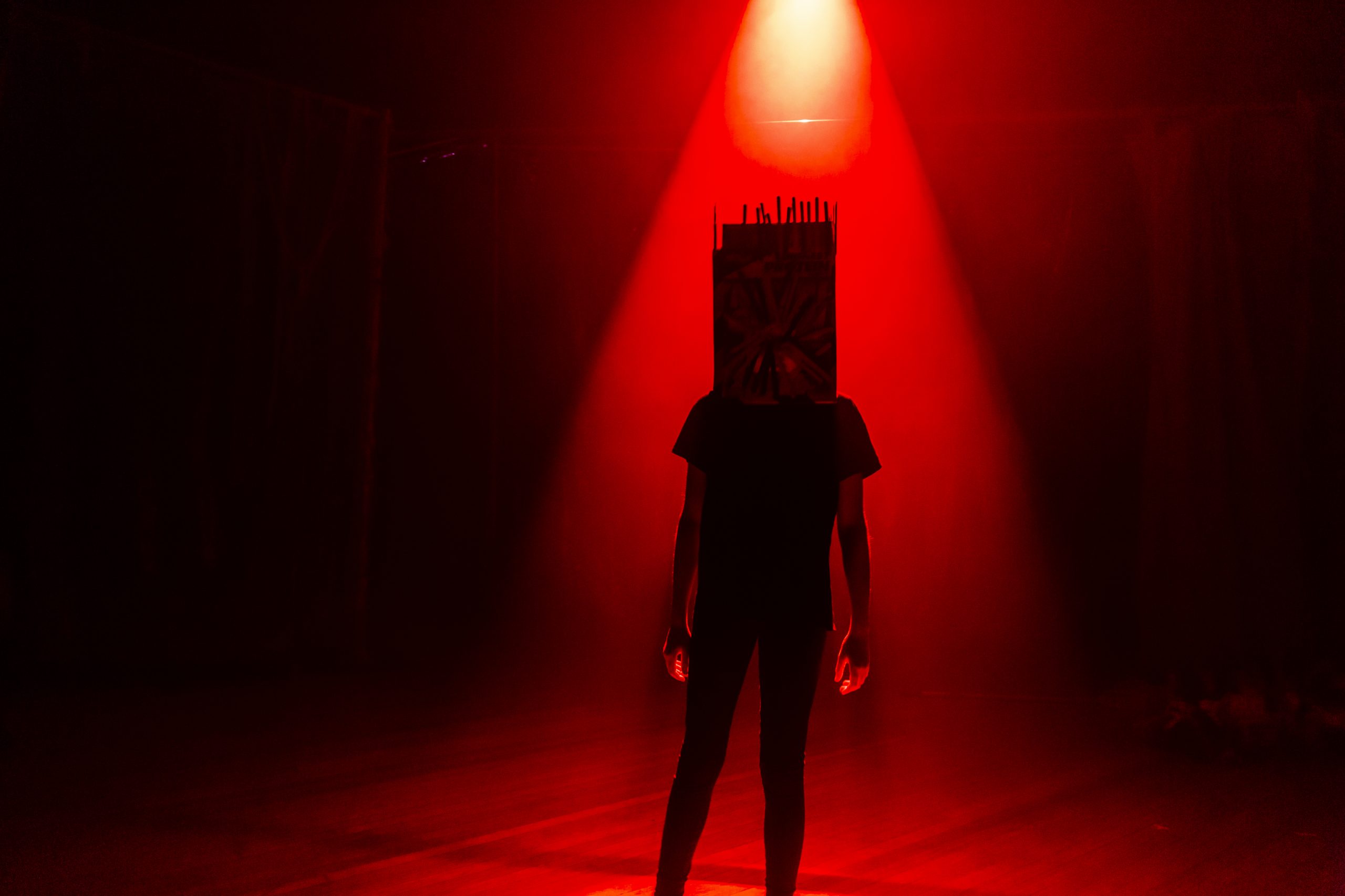

The workshops for The Cabin! ran throughout 2017 and 2018, exploring with the children a range of material connected to urban myths and horror stories. Gradually, a narrative, some characters, and some clear design directives emerged, which became the basis for a horror-comedy show known as The Cabin! JOF describes a “huge, rich tapestry of ideas” (Watts) that came from this development. The material was then brought into a process with the show’s creative team to develop the dramaturgical structure that would frame the ideas. Essentially, the structure of “the children’s variety show,” hosted by “the worst theatre director ever” emerged as a framework to showcase the visual design, characters, stories, sounds, and images the children had developed through the workshop process. The ideas and writing from the children were sometimes executed and realised by professional artists (for example, the ‘Messy Monster’ who featured in the show was a story and drawing by a ten-year-old in the UK and executed as a three-metre-high Bunraku-style puppet by professional designers and operated by the child performers). Oftentimes material went into the show exactly in its original form; for example, the two-page monologue executed by the Secretary character played by adult performer Emily Tomlins toward the end of the show.

Our rehearsal process consisted of a week-long creative development intensive during the April school holiday period in 2019, followed by a series of rehearsals after school and on weekends in the lead up to the July premiere, which took place at the Northcote Town Hall in Melbourne and ran for a critically acclaimed two–week season. This rehearsal flow is child-centric; it works around children’s availability and a pattern of deep immersion and short engagement. It also requires adult collaborators to be elastic — to expand and contract with the process in a manner that is not always familiar to mainstream rehearsal processes, which usually offer a deep immersion over a period of six to eight weeks. This notion of elasticity, of expanding and contracting within the rehearsal process itself, disrupts dominant power relationships within a collaboration as it decentres adult-centric notions of ‘work’ and replaces them with the more child-centric notion of play. Rehearsal processes that are geared around children’s timelines and designed for children’s maximum participation and enjoyment require adult collaborators to put aside dominant ideas of the process of making a show and embrace a process that expands and contracts with the needs and timeframes of children.

There were eleven children overall in the cast aged between ten and fourteen years. The cast consisted of two groups of five (known to us as Cast Blood and Cast Gore), and a teenage musician who featured in every show. The children all came from my existing networks within Youth Arts, and I had worked with all but one of them on other creative projects in the last three years. The children came from a broad range of familial, religious, cultural, and socio-economic backgrounds, and lived between Balaclava in the south of Melbourne and Meadow Heights in the outer metropolitan north of the city. Some cast members presented with mild learning disabilities, and one had English as a second language.

My existing relationship with all the families, children, and parents involved in the project meant that from the outset there was a significant amount of trust and goodwill to work with, which was useful for explaining to parents that the project was a horror show, written by kids for adult audiences. In my journal I note that:

There is some initial surprise and concern at the theme and content of The Cabin! and one parent has specifically described that her child is afraid of horror and recently spent two weeks in [the parent’s] bed after exposure to some frightening horror-movie material on the internet. This has set up a series of rehearsal ideas for me about how to demystify the horror genre, and reveal how theatre can create horror tropes, or how horror exploits ideas of tension and release in the audience. (Austin, personal journal entry, March 23, 2019)

Additionally, toward the end of the rehearsal process, we introduced what we termed the ‘Destruction Crew.’ Made up of seventeen second-year acting students from the Victorian College of the Arts (who I had been teaching that semester as part of their degree), the Destruction Crew were specifically brought into the process to help create a series of images and theatrical moments, and to devise an apocalyptic final scene. Like with the other creatives, I started the process with the Destruction Crew by positioning the rights-based framework of working with children and young people at the forefront of their experiences. From a journal entry reflecting on their first rehearsal with The Cabin! cast, I have written:

Today when the Destruction Crew started I told them that this was an invitation being extended by the children to participate in their world. This invitation was generous, but the acting students must remember that this is a world where children are functioning as creative agents, with equal ideas and input to all the adult collaborators. I was delighted by their response to this, and at the ease with which they cast their ego aside and engaged in the rehearsal tasks and activities as collaborators with the children. I have struggled at times to get professional artists with years of experience to do this! It was almost as if it was actually easier for the students! (Austin, personal journal entry, June 28, 2019)

This last note in my journal is pertinent. As students of theatre, the Destruction Crew are immersed in a learning framework about the experience and conditions of making theatre and thus found it easy to adapt immediately to the idea that the usual adult-child contract did not exist in the same way in this space. To this end, they demonstrated an elastic understanding of the adult-child relationship and the way a creative process might work. They demonstrated expansive thinking, embraced the notion that the child collaborators had worthy and astute creative observations, and could be flexible and pull back from their own behaviours and assumptions. While not always true of all artists with more professional experience, I would suggest that, in my experience, it can be difficult for adult professionals to unlearn their ingrained habits of practice, to resist the expert-amateur dichotomy inherent in the adult-child relationship, or to embrace the idea of thinking through new ways of making. In order for a rights-based practice with children to succeed, it is critical that all adult collaborators have the same view of children — not as future people, but as people right now — and that they are prepared to concede modes of power or be elastic and flexible in a creative process. At times, this may mean putting aside any artistic ego and supporting new ways of seeing and experiencing the making process. As lead performer and artist Emily Tomlins noted in an interview with Richard Watts on the SmartArts program on RRR radio before opening night, children should be seen “not as future makers, but as collaborators and present-makers” (Watts), and a shared understanding of this idea amongst central adult collaborators is critical for fostering an equitable process where cultural agency can thrive.[6] Selecting collaborators who can embrace these ideas and contexts for projects that adopt a rights-based framework of creative practices is critical for the success of this model of making performance. This requisite for adult collaborators of embracing uncertainty, being open to possibility, subverting power relations, and conceding power reflects how the notion of elasticity intersects meaningfully with the features of a rights-based approach to practice.

Although the script for The Cabin! already had shape by the time I started on the project, it was important from the outset of the process to make time for story-sharing between key creatives, including child performers, based on the theme of the show. This methodology works as an interpretive process that connects the material in the written text with the lived experiences and imaginative world of the performers. Gay McAuley identifies that where there is an existing written script, rehearsals will commonly start with a group reading of the whole text, and then a period of ‘table work’ as performers and creatives excavate the text for meaning, usually through reading it aloud (McAuley 5). In contrast, we began our first creative development with a series of brainstorms and story-sharing exercises exploring “what makes something scary” and “what are the things that keep you awake at night” without ever looking directly at the written text. We listed all the ideas put forward by the children in response to these two ideas; we grouped these responses into categories (inside/outside, real/not real, etc.) and discussed common themes that were emerging. Children shared their experiences of being scared by something, told stories of various times that something had frightened them or when they had experienced a fright, and we discussed how fear manifests in the body. We used the physical responses to create a short improvisation that saw both adult and child cast members develop a series of gestural patterns related to how fear affects and sits in the body. These gestural patterns formed a key part of the movement vocabulary for the performance, enabling the child performers to take creative ownership of their character’s physicality with an understanding of what thinking underpinned these artistic choices and to demonstrate their imaginative elasticity. It is important to note here that children were invited to share stories, not requested to. As in all group dynamics, some were very keen to share, while others took some time to feel safe and were encouraged by the participation of the adults and their peers in the process. In the end, all children shared something, but they were not required to; an elastic engagement with the task, whereby the child collaborators were able to sit at a distance or up close and personal as and when they desired, was fostered.

The psychoanalytical concept of the “holding space” (Winnicott; Mclean) was a useful convention to apply throughout the rehearsal period and supported the attempt to create a space that was both brave and safe for the performers and, as psychiatrist Mark Epstein has described it, would enable their “uninterrupted flow of self” (Epstein 30). Arts education theorist Judith McLean suggests that without fostering a space in which children experience trust and feel safe, little real collaboration can take place (Mclean 49). The challenge within a creative process then is to create an environment in which children are meaningfully interacting and engaging with adults and with complex and conceptual ideas, while experiencing an inversion of the social code between adults and children, which governs many other spheres of child engagement, particularly the domestic and educational contexts that are most familiar to them. The way this space is managed must allow children to feel safe to take risks, to participate, engage, and ask questions. This tactic of holding space utilises concepts of elasticity relating to how the boundaries of spaces expand and contract through dialogue and how relationships and ideas within the space are moveable and responsive. The fostering of this space is a key task of the adult director on contemporary performance projects working with children as collaborators. Further, it directly responds to rights-based ideas of engaging in an age-appropriate dialogue with children, which recognises the adults’ complicity in constructing ideas of children’s vulnerabilities (Tobin 182; Shier 107).

The following section details one of the specific strategies I used as part of ‘holding space.’ This strategy was designed to foster an environment that worked to subvert dominant power relations between adults and children, connecting the rights-based approach I was applying to other human rights frameworks and contexts.

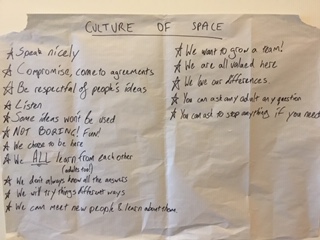

On Day One of rehearsals, directly after the Acknowledgement of Country, the entire team (creatives, designer, cast, stage managers, etc.) collaborated to create a document (see Figure 1 below), which I term the “Culture of Space.” Creating this document is designed to acknowledge that, in this space, adult-child relations may function differently to other spaces and to detail what expectations we might have of each other. This document was on the wall of every rehearsal space in every rehearsal; we acknowledged and updated it as we progressed through the process. Designed to function on a number of levels as a tool for addressing consent and safe spaces protocols, this document aimed at working through the idea with the children that they were able to say “no” at any time, to anything, and that that right would come without penalty. We explicitly addressed how this meant you could say “no” to anyone at any time, advise that you were uncomfortable or didn’t want to do something, and that no one was going to get cross with you or tell you that you were no longer able to participate in the show. “No” was an available option to everyone in the space to apply without fear or favour. We also discussed that we wanted to create an environment where you wanted to say “yes” to things because they were exciting, or different, or challenging; but it was always okay to say “no.”

The Culture of Space document enabled a contractual understanding of the behaviours and values expected by all collaborators in the process. It set up ideas of the mutual exchange of learning between adult and child, and the critical notion that the process is not linear and that we don’t always know the answers. We began to use the terminology “hold on tightly, let go lightly” to describe how ideas might fuel a moment, but were sometimes not the right fit or piece of the jigsaw puzzle to move something forward. Idea contributions may not all be reflected in the final work, but that neither means that they weren’t useful at the time for moving to the next idea, nor that the idea will not return to you at some later point and be useful for the next work one might make. Providing this context for child performers is a critical part of establishing the practice of cultural agency in the process and addressing how democracy and choice might work in the collaboration. It situates the notion of elasticity within the development of ideas; it reflects the way in which a process is conceptualised with children as a series of moving towards things and moving away from things with fluidity and flexibility. It is also an understanding that most adult artists already have, so introducing the concept to child collaborators is useful for positioning them equitably. Adapting adult understandings of creative processes for children is a further example of an elastic mode of working, where a rights-based approach intersects with inclusive arts practice. It asks adult collaborators to rethink and reconceptualise embodied knowledge, so that it might be shared and made accessible to a broad range of collaborators.

Within a Youth Arts pedagogy, it is highly unusual to create new work in a model where a script is written by unknown other children who are not present in the rehearsal process and then brought to life and performed by a different set of children. There are complicated issues that arise here around intellectual property and agency, and I don’t think these issues were necessarily addressed in the project design and realisation. The ‘borrowing’ of children’s ideas was publicly acknowledged throughout The Cabin! promotion and part of the public discourse surrounding the work. Indeed, the show was billed and promoted as a “horror story written by kids for adult audiences.” JOF was quoted on the Australian Arts Review website as saying: “Everything from the set, characters, and sound has been designed by primary school students to create a gory, truly horrifying, and darkly comical theatrical experience for their adult audience” (Australian Arts Review 2019). While this was the case, the dramaturgical hand of the adult artist was certainly present and evident in the work, as this quote below from reviewer Suzanne Sandow of Stage Whispers suggests: “There can be no doubting the sincerity of the makers of The Cabin!, but it feels like it would more appropriately be labelled: A horror show inspired by genuine, strong and interesting ideas from kids — written, developed and mostly presented by adults” (Sandow).

There are still questions about ownership in terms of how the material generated in the workshops informed the work, and it is also important to consider that the space of the theatre critic is adult-centric. While professional theatre created with, by, and for kids is frequently (if not always) overseen, curated, or scaffolded by an adult artist, the extent to which this is visible can differ enormously (van de Water 20). I would suggest that future practitioners who work in this way consider how to attribute aspects of the work more closely to the children with the original conception, and that they foster explicit collaboration throughout a rehearsal process. It may also be useful to consider what contemporary theatre-making methodologies might offer for working within a paradigm of consent for collectively devised ideas.

What this analysis of the creative process of making The Cabin! demonstrates is that, through the application of a rights-based method of collaboration, it is possible to envisage how we might have a series of very important conversations with children about the role they play in conceiving new possible and radical futures. It also demonstrates that it is both the creative framework that must expand and contract accordingly and thus embrace elasticity, as well as the adult artists, if the collaborative process is to resist dominant notions of children and childhood and subvert the adult-centric lens. I would suggest therefore, that the rights-based approach to working with children in performance intersects with notions of elasticity as a central component of creative practice through the productive notions of expansion and contraction in a range of useful ways. As I suggest throughout the article, elastic approaches to the adult-child relationship, to notions of process and rehearsal, and to the passage and control of ideas all resonate within a rights-based approach to creative practice. My research also suggests that a rights-based model of practice does indeed go some way to addressing the power inequities that contribute to the ethical quandary inherent in an adult-child collaboration; it structures a paradigm that resists the idea of children’s vulnerability and focuses instead on their strengths and capacities (Senior 73). However, what my analysis also reveals is that the values and strategies that might be part of a process of creation do not necessarily translate to the reception of a finished work onstage. This finding in some ways brings the project full circle: I began this article by stating that this enquiry was in part driven by seeing performance work featuring children on stage where I felt the ethics of creation were questionable. Consideration of the frames we place around children in art and performance, and how these frames might serve to reinforce or subvert understandings of childhood and children, is key to the success of a rights-based approach to the practice of creating performance work with children. This research further suggests that the aesthetic outcome of a performance may not reflect a process where a child’s voice has been championed and their cultural agency platformed, regardless of whether these values featured as part of a collaborative practice or not.

See for example: Matthew Westwood. “PM says Henson photos have no artistic merit,” The Australian, 23 May 2008, https://theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/nude-teen-exhibit-not-art-rudd/news-story/5fc28c4c5ffd0ec7261d4ad4b34fb743. ↑

I take the term child and children to refer to people under eighteen years of age (the legal age in Australia) and young people to refer to those aged between eighteen and twenty-six years. However, when working with fifteen- to twenty-five-year-olds, I would use the terminology young people to refer to the group, so these are not fixed ideas, and there is slippage between categories. ↑

See ABC article, “Police quiz photographer over nude shots.” ABC News, 23 May 2008. https://abc.net.au/news/2008-05-23/police-quiz-photographer-over-nude-shots/2445936 ↑

You can read more about Alex Walker and her company House of Muchness here: https://houseofmuchness.com/about-founder. Accessed 12 April 2021. ↑

The Creative State Summit was an initiative of the Victorian Government and arose from the Creative State Strategy policy document released in 2017. Designed to bring together people working across the Creative Industries in a two-day forum, the inaugural 2018 Summit took place at the Melbourne Museum on June 14 and 15, 2018. You can read highlights from the event here: https://creative.vic.gov.au/showcase/great-minds-at-the-creative-summit. Accessed 12 April 2021. ↑

You can hear more about what I think the necessary ingredients are for a working methodology that embraces play and cultural agency in my 2018 keynote at the Victorian Creative State Summit: https://vimeo.com/277576475/. ↑

Austin, Sarah. Personal journal of The Cabin! rehearsal process. 23 February-28 July 2019.

Australian Arts Review. “The Cabin!” 28 June 2019. https://artsreview.com.au/the-cabin/. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Bianka, Clifford, Adam, and Alima. Creative State Summit keynote speech, June 2018. https://vimeo.com/video/277576475. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Bradbury-Jones, Caroline, and Julie Taylor. “Engaging with children as co-researchers: challenges, counter-challenges and solutions.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology, vol. 18, no. 2, 2015, pp. 161. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2013.864589.

“Climate change strikes across Australia see student protests defy calls to stay in school.” ABC News, March 16, 2019. https://abc.net.au/news/2019-03-15/students-walk-out-of-class-to-protest-climate-change/10901978. Accessed 12 April 2021.

“Education Minister Dan Tehan lashes ‘orchestrated student climate strikes.’” SBS News, February 18, 2019. https://sbs.com.au/news/education-minister-dan-tehan-lashes-orchestrated-student-climate-strikes. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Epstein, Mark. Going on Being. Broadway Books, 2001.

Faulkner, Joanne. The Importance of Being Innocent: Why We Worry about Children. Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Giles, Sue. Young People and the Arts: An Agenda for Change. Platform Papers, vol. 54, Sydney: Currency Press, 2018.

Harvey, David. A Brief History of Neoliberalism. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Loreman, Tim. Respecting Childhood. Bloomsbury, 2009.

McAuley, Gay. Not Magic But Work: Am Ethnographic Account of Rehearsal Process. Manchester University Press, 2015.

Mclean, Judith. “Creating Inner Lives: Theories of learning, selfing, actioning through Arts Education.” Change: Transformations in Education, vol. 7, no. 2, 2004, pp. 48-59.

Sandow, Susan. “The Cabin.” Stage Whispers, 2019. http://stagewhispers.com.au/reviews/cabin. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Senior, Adele. “Beginners on Stage: Arendt, Natality and the Appearance of Children in Contemporary Performance.” Theatre Research International, vol. 4, no. 1, 2016, pp. 70-84. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0307883315000620.

Shier, Harry. “Pathways to Participation: Opening, Opportunities and Obligations.” Children and Society, vol. 15, no. 2, 2001, pp. 107-117.

Snyder-Young, Dani. “Youth theatre as cultural artifact: Social antagonism in urban high school environments.” Youth Theatre Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, 2012, pp 173-183.

Tobin, John. “Understanding Children’s Rights: A Vision beyond Vulnerability.” Nordic Journal of International Law, vol. 84, 2015, pp. 155-182. https://doi.org/10.1163/15718107-08402002.

UNCRC (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child). General comment No. 8 (2006): The Right of the Child to Protection from Corporal Punishment and Other Cruel or Degrading Forms of Punishment (Arts. 19; 28, Para. 2; and 37, inter alia).

Van de Water, Manon. “TYA as cultural production: Aesthetics, meaning, and material conditions.” Youth Theatre Journal, vol. 23, no. 1, 2009, pp. 15-21.

Walker, Alex. Creative State Summit keynote speech, June 2018. http://vimeo.com/video/277576475. Accessed 12 April 2021.

Watts, Richard. Interview with Joseph O’Farrell and Emily Tomlins. “‘A Huge Tapestry of Ideas’ Collaborated with kids to create Cabin! A Terrifying Horror Show.” SmartArts, RRR, 4 July 2019.

Matthew Westwood. “PM says Henson photos have no artistic merit,” The Australian, 23 May 2008, https://theaustralian.com.au/news/nation/nude-teen-exhibit-not-art-rudd/news-story/5fc28c4c5ffd0ec7261d4ad4b34fb743.

Winnicott, Donald. Playing and Reality. Tavistock, 1971.

The Cabin!

Created by Joseph O’Farrell

3-13 July 2019

Main Hall, Northcote Town Hall Arts Centre

Written by: Joseph O’Farrell, Emily Tomlin and 200 school students (UK/Aus)

Directed by: Sarah Austin

Performed by: Joseph O’Farrell, Emily Tomlins, Mariela Barajas Anderson, Zara Barajas Anderson, Chase Bryant, Billy Page, Manha Naseer, Joshua McDonald, Evie Fuggle, Archie Coffey, Izzy Rothenbuehler, Alice Kimpton Drake, Hunter Bishop

Sound Design: Steph O’ Hara

Lighting Design: Jen Hector

Set and Costume Design: Emily Barrie and Daryl Cordell

Stage Management: Rose Pidd

Produced by: Kate Hancock and Jo Porter