When Clare Croft was eight years old, waiting for rehearsal in a dance studio in her hometown in Alabama, someone taunted her with the epithet “queer”; although she didn’t know what the word meant then, it irrevocably set her apart from the other girls performing in that year’s recital (“Dancing Toward Queer Horizons” 57). Eventually, this isolation made her think about the temporality of queerness: what might be the “potentials of queer dancing futures to consider the radical possibilities for thinking with bodies?” Many years later, when Croft edited the anthology Queer Dance: Makings and Meanings — thereby summoning a diverse queer dance community that fills more than 300 pages — she wrote, “Queer dance’s investment in bodies as sites to imagine, practice, cultivate, and enact social change is not just an aspiration. It is a documented outcome of our queer dancing pasts” (Queer Dance 14). The dream of a queer future for dance that both reconfigures an alienating past and functions as the inevitable, radical, and collective fulfillment of that past relies on the work of a community skilled in queer utopian temporalities. Genealogies must be created from playfully defiant queer imaginaries rather than handed down by decree and birthright; inherited histories of shame, stigma, or subjection must be recast; communities must be gathered across vast dispersions of time and space. When ancestors cannot be unearthed in the archives, they must be intuited — or even called into being.

It is perhaps to be expected that, decades ago in Alabama, a young dancer like Croft would feel herself keenly alone, cut off from any queer lineage of dancing. But well into the twenty-first century, queer — and particularly lesbian, trans, and genderqueer — dancers are still bereft of robust communities, equitable institutional support, and a sense of historical visibility. This problem is exacerbated in ballet, as Western European courtly codes for bodies and movements have hardened over centuries into a nearly fossilized form. As Judith Hamera demonstrates in her book Dancing Communities: Performance, Difference and Connection in the Global City, today’s ballet studios present particularly intensified geographies of embodiment and sociality: ideally, classes and rehearsals become “utopian spaces and home places” (71). Yet many of the neighborhoods constructed by ballet remain unwelcoming — even openly hostile — to dancers who do not fit into its archaic, entrenched ideals of ballerinas and danseurs.

In 2019, Dance Magazine published an article titled, “Pride & Dance: Why Our Field Can Be Both a Haven and a Challenge for LGBTQ Artists,” in which twenty-seven-year-old Kiara Felder asks the searching question, “Could I be a ballet dancer and be lesbian?” (Felder qtd. in Scher, “Pride & Dance”). As a Black woman, Felder notes, she is used to being “a unicorn” in ballet, but in all the schools and companies she has danced with — North Carolina School of the Arts, Pacific Northwest Ballet, Atlanta Ballet, Les Grand Ballets Canadiens — “she’s always been the only queer women in the studio” (Felder qtd. in Scher, “Pride & Dance”). In 2020, Pointe Magazine ran a similar article, “For Queer Women in Ballet, There’s a Profound Gap in Representation. These Dancers Hope to Change That,” featuring dancers Lauren Flower and Audrey Malek, who attest to the fact that even when a major company like Boston Ballet celebrates Pride, it spotlights gay men while shunning queer women — or that, as Malek puts it bluntly, “People need to know that there are queer women in ballet” at all (Malek qtd. in Warnecke). This is not merely a problem in rural cities like Fresno, where Flower grew up; as Ashley R.T. Yergens — a trans man who left Minnesota in order to pursue a dance career — testifies, even in New York City’s purportedly liberated downtown dance scene, “he barely took class for five years” because of the pervasive cisheteronormativity (Yergens qtd. in Scher, “Pride & Dance”). For a young ballet dancer who reads these stories of trauma and exclusion, an internet search for “trans ballet class” is likely to corroborate Yergens’ testimony: several pages of Google results turn up only two options for ballet classes oriented towards trans dancers in the U.S. And one of those two, Cristina M. Michaels’ Queer Dance Project in Denver — which advertises itself as a “rare queer, transgender owned business” that exists precisely because “‘Queer or Trans’ and ‘Classical Ballet Training’ are usually not used in the same sentence” — has not yet even opened; instead, Michaels posted her first instructional video in November 2020 (Michaels, “Queer Dance Project”). A month earlier, in a blog post titled “Ballet & Transphobia,” she had called mainstream ballet “a well-oiled discrimination machine,” noting that most studios and classes “are part of the systemic culture of intolerance & transphobia.”[2]

As the next generation of queer and trans dancers arrives in ballet studios, therefore, they continue to find that “there are still challenges, especially when it comes to certain opportunities being taken away.[3] A lot of companies and studios where I danced as a male aren’t receptive to me as a female,” eighteen-year-old ballerina Jayna Ledford reported in Dance Spirit in 2018, concluding, “Hopefully, ballet will slowly start to open its doors to trans dancers.” The fact that Ledford’s brightest hope is the eventual possibility of slow change illuminates the current landscape of ballet: the gleaming façades of DEI statements, the discrimination and inequality just underneath. While trans, genderqueer, gender-non-conforming, and non-binary identities are becoming more widely recognized in the U.S., persistent — and racialized — inequities in access to health care, safety, wealth, political power, housing, education, employment, and public cultural life are ever more sharply apparent. “We have no way to anticipate what these accidentally synchronous changes will mean for how we collectively understand trans becoming and movement potential,” performance theorist and critical historian Julian Carter notes, reflecting on his “Transgenderational Touch Project” in 2018, “but we do know we will need to pay extra attention to connecting across trans- generations” (SEX TIME MACHINE).

Delving into queer and trans histories in order to support the “impending futures” of young trans artists, Carter proposes an experiment in embodied sociality “for touching the trancestors.”[4] What we need, Carter concludes, are artists who can create “a reparative gesture toward several different pasts, and a promise to nurture several different generations.” We need histories that do not reify the erasure of queer and trans people,[5] canons that do not relentlessly elevate the achievements of cisgender heterosexual white men above all else,[6] and twenty-first-century social spaces that do not condemn young artists to hoping that maybe, slowly, somehow, institutions might start to crack open their grand gilded doors to admit different bodies. Ballet, in other words, needs the kind of “reparative gesture” that not only re-imagines studios, companies, and classes as inclusively utopian, but also re-envisions ballet history in a queer temporal mode: a way of “touching the dancestors.”

In his chapter in Queer Dance on ballet’s “alternative futures,” Julian Carter posits that it is only when we recognize “the imperial history of ballet,” with its “entrenched systems of power and oppression,” that we are able to “launch our own changing and reiterative futures” (“Chasing Feathers” 121). We might begin, then, with the usual near-hagiographic accounts of Catherine de Medici and Louis XIV, with orchésographie and the ancien règime, with what is literally called danse noble. But the recentering of traditional ballet historiography — at least for queer and trans purposes — is temporary and instrumental, a sort of locating device for the concentrations of “power and oppression.” Once its sites and systems are mapped, it is time, as VK Preston writes in their dissertation on Baroque dance, to contest “triumphalist narratives of ballet” that glorify “the magnetic specter of the sovereign,” and to focus instead on “unruly” dancing bodies, especially “multiplicities, ensembles,” and “socially marginalized populations” (13, 247, 22, 2).[7] If we begin with the monarchs and the courts, it is only in order to find a place in ballet history for the villagers.

In that spirit, let us retell the origin story of ballet as seen “from below,” from the perspectives of those evicted from its realm in order to create a danse noble — as if ballet were a neighborhood gentrifying in the fifteenth century. At that time, certain dance forms were being roped off for the aristocracy of Italian courts, their steps polished to a genteel sheen, thereby leaving other dances — notable for their liveliness, popularity, accessibility, expressivity, elasticity, variability, and communal feeling — to the common people. The first kind of dancing, refined and ossified, became ballet. It exemplified the hard architecture of status: “a specific order in dance attributes a precise role to each sex,” dance historian Ludmila Acone explains, “and contributes to the maintenance of the gender, social, political, and spiritual hierarchy in courts” (141). The second kind of dancing — ordinary people practicing and performing together “in village fêtes, private house parties,” or as participatory “round dances” — was sparsely documented and went the way of much ephemeral early modern popular culture (Sparti 52). Thus ballet, reified into a monolith of white European high art, seemed to have expelled any taint of the common, the popular, the participatory. Whatever had been unruly, versatile, improvisatory, and expansively communal was banished as ballet prioritized orderly, codified form. Instead of circles that stretched to include any villager who wished to dance, there were court ballets secluded behind castle walls.

At this point in the story, just when it seems like all the house parties are over, something queer happens. The past cracks open, and a dissident history unfolds. The villagers do not accede graciously to the inevitable dominion of danse noble and, somewhere in the dusky neighborhood of the queer imaginary, the dancestors gather for a defiant round dance that will conjure a future for people like Flower and Yergens. In this queer version of ballet historiography, the twenty-first century offers a chance for a “reparative gesture” that restages and speaks back to the moment when ballet cast out its villagers. Otherwise, although mainstream ballet may be successful as an elite contemporary artform — New York City Ballet (NYCB) enjoys an annual operating budget of approximately $88 million for its professional company alone — without the village fêtes, the house parties, and the round dances, where is the spirit?[8]

When Flower talked about the persistent loneliness of being a queer woman in ballet, she mentioned one exception — one company that explicitly featured dancers like her (Warnecke). When Yergens mourned the fact that he lost five years of his life as a dancer because he didn’t “feel welcome in classes” while transitioning (Scher, “Pride & Dance”), he did find one technique class that seemed like home — one place where, as “a self-proclaimed queerographer,” he could take class without having to compromise his gender, his sexuality, or his “blue-collar queerness” (La MaMa Blogs). That one company, those few classes, and that community — that is, those actual “utopian spaces and home places” for queer and trans dancers in ballet — are called Ballez.

Dreamed into being in 2011 by Katy Pyle, a white genderqueer lesbian choreographer, Ballez “is just what it sounds like, it’s lesbians doing ballet. AND Ballez is not just lesbians, it’s all the people whom ballet has left out” (“Ballez”).[9] At first, Ballez was a class on Thursday evenings at Brooklyn Arts Exchange (BAX) that was not only open to all levels of dancers, but also explicitly inclusive. To reshape ballet around lesbian, queer, gender-nonconforming, non-binary, and trans bodies, a studio cannot merely be “gender-neutral,” Pyle underlines, but must be pro-actively “gender-expansive” (Whittenburg). Ballez classes are designed to support a community of people dancing in their genders and partnering as they desire. In a typical Ballez class or workshop, Pyle recounts,

we explore the virtuosity of genderqueer embodiment, practice energetic mirroring, learn inclusive partnering techniques, seek out (and destroy) our culturally constructed biases, and discover new freedom to witness the beauty of one another as we dance to the beats of queer icons! (“Adult Ballez Workshop”)

In rallying their community to re-appropriate ballet, Pyle stretches the rhetoric that undergirds Western classical dance. “In ballet training,” dance theorist Ariel Osterweis observes, “technique is learned within an ideology of perfecting an imperfect body” (74). In contrast, Pyle deliberately queers the terms that ballet uses to indicate its competitive exclusiveness (“virtuosity”), its neurotic relation to corporeality (the infamously anorexia-inducing mirrors of ballet studios), its relentless heteronormativity (“partnering”), its hyper-valuing of whiteness (“culturally constructed biases”), and its exploitative scopic traditions of male spectators preying on female ballerinas (“witness the beauty”). Valuing the genders, bodies, and sexualities that dancers are bringing into the studio affirms queer and trans selfhood against a history of clinical and moral pathologizing. Arguably, the most radical move Ballez makes is to shift the concept of “virtuosity” from technical mastery of steps to the practice of “genderqueer embodiment” in itself.[10]

“What brought you to Ballez?” Yergens was asked in 2016 (La MaMa Blogs). “A fiery desire to queerly move in political, technical, and sexy ways,” he replied. Pyle, who has been dancing since they were three years old, endeavors to make Ballez the place where that conjunction of desires is possible, striving “to change the form of ballet into what it could be: a place of joyful expression, passion, beauty, complexity, diverse representation, and respect” (“Ballez”). That is, they do not see ballet as inherently a restrictive domain of whiteness, cisheteronormativity, class privilege, ableism, and the kind of femininity that only admits waifs and sylphs. Rather, they believe in a queer potential for ballet’s elasticity: that the form can be expanded beyond the exclusive, often damaging structures it has historically upheld. In this sense, Pyle undertakes the simultaneously hopeful and enactive “utopian performative” theorized by feminist theater scholar Jill Dolan (22). By doing ballet as it might be done, they help to instantiate the possibility of inclusive ballet.

Yet rather than striving for straight, linear progress toward this utopia, Pyle engages a queer temporal framework, one that envisions futurity through a “queer restaging of the past [that] helps us imagine new temporalities” (Muñoz 171). Ballet’s early history shows that the intensification of sex-gender normativity is yoked to class stratification not only in terms of the bodies it admits but also in the orientations it allows for artistic lineages. The hard architecture of ballet fixes both genders and genealogies in place, forcing ‘straight’ lines for bodies and the legacies they inherit. For this reason, Pyle is an apt historiographer for the “alternative futures” and queerly imagined dancestors of ballet. In fact, the mission statement of Ballez is the fulfillment of our queer origin story about ballet: “WE who have been deemed unworthy of the pride, nobility, and belonging in ballet’s centuries-long hierarchical history… are coming back into the castle now” (Pyle, “Ballez”).

Pyle’s characterization of ballet as a “castle” illuminates the institutionality that Western classical dance maintains even today; it is a dwelling for the elite and thus a site for ideologies of ‘nobility,’ ‘elevation,’ and ‘pure line.’ At the same time, Pyle highlights the material realities of ballet: it is a towering, fortified monument with a well-guarded entrance, constructed out of the most obdurate, enduring elements available to European culture in the fifteenth century. Perhaps for this reason, Pyle’s approach to ballet resonates with queer phenomenologist Sara Ahmed’s mode of “looking back” at or “behind” apparently solid institutions and objects (178, 143). As Ahmed puts it, if inheriting the normativity of the past would entail the erasure of your embodied identity, then necessarily “queer politics would also look back to the conditions of arrival,” in order to “trace the lines for a different genealogy” (178).[11] In “looking back” critically at this history, then, Pyle stages a queer return to that crucial moment when ballet became less like a kind of dancing and more like an edifice of elitist cisheteronormativity.

Pyle seeks to recover the double potential embedded in ballet’s history: to return to that mythical moment when ballet cast out its villagers and solidified its gender roles, and to dance it differently. Those who have been banished from “straight time’s rhythm,” queer performance theorist José Muñoz notes, “have made worlds in our own temporal and spatial configurations” (182). In their book Time Slips: Queer Temporalities, Contemporary Performance, and the Hole of History, performance artist and scholar Jaclyn I. Pryor writes, “I want to believe in repair after trauma, in making whole what has been smashed. I want to pass through the hole of time, and arrive someplace queer and new” (152). It is this kind of historiography — queer and trans, recuperative and interventionist, perverse and hopeful — that Pyle undertakes for ballet. If the “conditions of arrival” of this artform have been the disenfranchisement of villagers from their own dances and the shaming of their bodies, Pyle will revisit that moment of trauma in order to trace a different possible genealogy. With camp wit and activist anger, they propose a vision of ballet as expansive, flexible, collective, reparative movement: ballet for the villagers, then and now. Their queer re-staging of ballet history demonstrates how an elastic sense of temporality — that artists can “pass through the hole of time” — creates space for the work of stretching the form of ballet itself. And when the rigid hierarchies of ballet are challenged, an inclusive queer sociality of participatory dancing becomes possible. There may once again be round dances. They may, in fact, take back the neighborhood.

Ballez thus acts as a battle cry — “lez dance our way through to the revolution!” — and as a practice for re-imagining ballet class, from the warm-up to the révérence [final bows] (Pyle, “Ballez”). This means, for example, that when Pyle explains the ballet term “fondu,” they confirm that it means exactly what everyone suspected: “that’s right: it’s cheese” (Ballez Company, “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 6: fondu + rond de jambe”). It’s about melting, feeling drippy and emotional, and being unabashedly cheesy. Pyle plays an Indigo Girls song and encourages everyone to “drop down into your sad fondu feelings,” curving the back. Similarly, in introducing pliés, Pyle notes that it means to bend, which entails not only bending the legs but also “bending the rules of gender expectations around this movement” (Ballez Company, “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 3: pliés”). Emphasizing the affective and political intertwining of these movements, Ballez classes encourage dancers to stretch, soften, melt, curve, and bend — elastic aspects of embodiment. To broaden the circle for those without previous training, Ballez classes demystify ballet in specifically queer ways: collective processing, camp references, dyke nostalgia, fluid gender presentations, and lots of feelings.

Once Ballez became a class at BAX, it also became a collective. Various dancers take turns teaching technique, ensuring that the voice (and body) of knowledge is diversified. Since in ballet, “virtuosity emerges through the trope of the soloist, further exploited via capitalist ideology’s reliance on commodity exchange and the cult of individualism,” this distribution of labor counteracts a key part of ballet hierarchy (Osterweis 71). Spatially, the ballet barres for a Ballez class are set up in a circle rather than in the traditional straight lines, so that dancers face each other during barre exercises — an echo of the round dance. Madison Krekel, a multidisciplinary artist who was involved with Ballez for three years, describes this choice to me as “pretty brilliant,” because “simple things that change the room” mean that “when you do a plié, you’re always going to be facing somebody.” She characterizes the warm-up sequence as an exercise in the service of stretching toward other dancers, looking at them, and eventually partnering them. This collective ethos was amplified when Ballez became a company, presenting its first evening-length performance, The Firebird: A Ballez, in 2013.[12] As one self-identified “ballezbian” put it, dancing with Ballez “enable[s] us to collectively rehearse our participation in a future that is more equitable and less painfully exclusionary” (Werther 57).

In the same way that Ballez choreography foregrounds interdependency — Pyle’s Sleeping Beauty & the Beast[13] opens with a dance that collaboratively weaves a circular web of yarn across the stage — the company prioritizes the well-being of its members. In a group interview in 2014, dancer l.n. Hafezi noted that “Ballez, by design, has an unusually large cast of minoritarian bodies in downtown dance where there’s already no money. Despite these conditions, I experienced really excellent, fair labor practices”; Pyle compared the company to a “‘co-op’ with worker-owners” (Hafezi). Ballez also provides a home for dancers who have been exiled by the uptown ballet patriarchy.[14] Equitable, diverse, community-oriented, anti-racist, body-positive, feminist, pro-worker, and gender-expansive, Ballez pursues a vision of ballet that is antithetical to everything mainstream ballet has become.

In terms of money, prestige, and worldly success, it is undeniable that mainstream ballet dominates the field; Ballez is a ragged little band of dancers with day-jobs, and Pyle has to fundraise tirelessly in order to pay them fairly. But as long-time New Yorkers know, even the most gentrified of neighborhoods harbors the ghosts of its former inhabitants. They trouble the sleep of the aristocrats. They rattle the doors of the castle. With their house parties and their queer hauntings, they evoke histories of place that are not merely nostalgic but actively unsettling. They are always unearthing awkward memories, geographic palimpsests, discomforting reminders of eras that late capitalism would prefer to erase. Before this was Luxury West Chelsea Condos for Sale, it was Fem 2 Fem at The Roxy (Shockey).[15] Before this block was dominated by the Soho Apple store, it was the home of the Indulgence party at Casa La Femme. Before this was the David H. Koch Theater, named for the far-right fossil-fuel robber baron (Goldmacher), it was the middle of the Lenape island of Mannahatta.[16] Now it’s the resident theater of New York City Ballet.

As soon as the word got out about Ballez classes, Pyle began receiving emails from people they’d never met. One message came from a trans teenager named Ely who lived in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Ely wanted to start taking ballet, and asked Pyle if they had any advice on how to find a good local class that wasn’t horribly cisnormative. “I sat with that email for months,” Pyle told me, “and I was crushed. I had nothing to give.” If people like Ely didn’t live in one of the five boroughs of New York City, there was no Ballez class for them.

This created an unforeseen paradox: the heart of Ballez is a queer sociality that celebrates embodiment in community. It is a gathering; its cheerfully camp motto is “We’ll see you at the barre!” (Pyle, “Ballez”). Dancers like Krekel emphasize the importance of “starting rituals” in the class, like the opening circle where people can say their names and pronouns or state explicitly what they have “felt ostracized from in regular ballet class” (Krekel). But what if, in order to support the embodied identities of people like Ely, the community itself needed to take on a geographically dispersed form? What if the only place to gather was the disembodied, asynchronous, and often troll-ridden placelessness of the internet? By expanding beyond the neighborhood and into digital realms, would Ballez be stretching itself too thin? Navigating this paradox meant drawing on a local network of lesbian community resources — a collaborative creative process that comes naturally to Pyle — while grappling with the neoliberal rhetoric that calculates potential ‘target users’ of a ‘digital product.’ The initial stage of the project was thus a classic example of lesbian sociality: a dream project, very little money, a DIY ethos, improvisatory flexibility, and the generosity of queer community. Pyle asked Courtney Powell, whose hair they have been cutting for years, if she would collaborate with them on creating a series of free YouTube videos of do-it-yourself Ballez classes. Powell, who was a producer for RuPaul’s Drag Race, agreed enthusiastically; she also pulled in her partner Tate Nova, who has a production company, to provide a Director of Photography and gaffers. Another friend, Alison Midgley, helped Pyle to rent a ballet studio at Brooklyn Academy of Music (BAM) where they could film for two days on a minimal budget. Pyle was committed to paying the dancers and the film crew for their work on the video shoot; in the summer of 2017, therefore, the Kickstarter campaign for Ballez Class Everywhere went live.

The second phase of the project raised more complicated issues: what happens when an explicitly lesbian DIY project like Ballez Class Everywhere is framed within a neoliberal social-media economy? Pyle is adept with platforms like Kickstarter — all three of their crowd-funding campaigns have been successful — but they have also been open about the fact that they’ve taken to social media because of a lack of institutional support. Crowdfunding might be idealized as a fluid, rhizomatic strategy for assembling resources from a community, yet Kickstarter is problematic: it’s a flexible network, but it’s also a corporate answer to the gaping hole where equitable national public arts funding could be. Moreover, the platform takes eight to ten percent of the money gathered by the artist. With its model of gamified meritocracy, it’s closer to technocratic corporate capitalism than to any lesbian DIY spirit; a “stretch goal” may use the rhetoric of expansive elasticity, but in fact it conveys the anxious neoliberal pressure to acquire more, to strive continuously and competitively under threat of austerity. It is notable that the only time that Ballez has “had quite horrible trolls,” Pyle told me, was when their project was featured on Kickstarter’s Facebook page.

While widespread disillusionment with social media is a new phenomenon — currently exacerbated by the bleak fact that massive numbers of Americans are turning to GoFundMe to pay for basic health care — inegalitarian funding models have troubled ballet since the beginning. “For too long ballet has upheld the values and desires not of its dancers,” Pyle notes, “but of the wealthy straight white male patrons that have dictated its budgets, and thereby, its expression” (“Ballez”). The ongoing problem, in other words, is the nature of patronage itself. When the aristocracy picks its preferred art forms, it selects for the qualities that it already idealizes, covets, or arrogates to itself. Thus, early court ballets were less about dancing than about the elaborate pageantry of displaying wealth; thus, classical ballet came to fetishize ‘pure line’ not only as a physical form, but as a sign of the racialized status of ‘nobility.’

The arrival of online crowdfunding has not redeemed ballet from patronage, in part because major mainstream institutions have already secured their philanthropic funding streams and stabilized their status as elite brands. For example, American Ballet Theatre (ABT) — the other renowned ballet company in New York City — frets that its annual operating budget is only around $43 million a year; its Artistic Director openly voices the desire for “a billion-dollar endowment” (Schaefer). As Bloomberg journalist Brian Schaefer reported, in 2016 ABT made “a smart investment in one of its strongest assets,” undertaking “a five-year, $15 million campaign” to support the work of choreographer Alexei Ratmansky, “a perfect fit for the ABT brand and a boon for its bottom line.” Undeniably, Ratmansky is a perfect fit for the ABT brand; like ABT’s Artistic Director and the Chairman of its Board of Trustees, he is a white cisgender heterosexual man honored by a world-class ballet company that did not promote a single Black ballerina to principal dancer until 2015. Aspiring ABT dancers take class at a school named for Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, who famously proposed the fantasy of American royalty — a ‘Camelot’ in which she figured as a heroic, stylish queen. Even when American ballet purports to have no aristocrats, the system of patronage continues its patterns. Even if the castle is merely a metaphor, it looms over the field of ballet in the twenty-first century. It is no wonder, then, that Pyle has envisioned a “Matronage” for Ballez. Dreaming of “a joyful, expressive, generous, radical, and gorgeous intersectional queer feminist future,” Pyle asks for monthly donations from a tiny circle of supporters (“Ballez”). For $5, you get the satisfaction of a “Butch Nod” to enable outreach; for $15, there are “Dégagés Against the Patriarchy” to pay one dancer for one hour of rehearsal.[17] In the meantime, ABT holds its fall seasons at the David H. Koch Theater.

As a web-native project, Ballez Class Everywhere (BCE) also raises affective and somatic questions about the elasticity of queer community in the digital age. “You can be with us, even if we can’t be with you,” Pyle says in the Kickstarter video, looking straight into the camera. This heartfelt promise evokes a wide range of other queer and trans social-media video projects in community-building. From dissecting the early trope of “It Gets Better” (Gal et al.) to sorting out the surfeit of YouTube coming-out videos (Lovelock), and from unpacking the “intimate publics” of online spectatorship (Bean) to discussions of temporality in the vlogs of trans men (Horak; Eckstein), scholars have examined the tensions in LGBTQAI+ online content. BCE videos are loosely related to a number of these genres: like the “It Gets Better” series, for example, they are aimed at people whose youth, non-urban location, or restrictive home/school setting means they have less direct access to queer communities. To justify the need for Ballez, one dancer says wearily: “Elementary school. Middle School. High School” (Pyle, “Ballez Class Everywhere! Kickstarter”).

However, whereas “It Gets Better” has been widely critiqued for its biases — one study found that sixty-one percent of the videos featured only men, seventy-eight percent of them white — and for its homonormative vision of monogamy, BCE showcases a diverse range of dancers and offers non-binary forms of partnering (Gal et al. 1707).[18] More closely related to transition vlogs by and for trans men (Raun, “Archiving the Wonders of Testosterone via YouTube”; Horak; Eckstein) and make-up tutorials by and for trans women (Raun, “Capitalizing intimacy”), BCE videos blend skilled, practical instruction with an emotional affirmation of gender-expansive practices. The mood of a Ballez class is simultaneously earnest, vulnerable, ironic, allusive, and camp, an affective mode familiar to audiences of queer screen performances from “LEAVE BRITTANY ALONE!” (Christian 369) to RuPaul’s Drag Race. As Krekel said to me, for those with a long history of ballet training — “I’ve been doing this shit since I was four years old!” she commented wryly — getting to do the jumps you love without the usual cishet constraints can feel “transformative.”

In addition to its queer context, Ballez Class Everywhere also joins the realm of dance-instruction and social-dance videos circulating on YouTube. Dance scholar Harmony Bench has argued that dances on social media can “reassert a social priority for dance,” because they encourage circulation, embodied emulation, and dialogue over the quiet, passive model of an audience in a proscenium theater (“Screendance 2.0” 184).[19] At the same time, dance videos on YouTube raise serious questions about representation, labor, ownership, and transmission practices. In particular, issues around race, gender, and sexuality have come to the fore in case studies including the Harlem Shake (Soha and McDowell), twerking (Gaunt), and above all Beyoncé (Bench, “Single Ladies”; Kraut; Thomas; Werner). Scholars have illuminated the ways in which communities already vulnerable to exploitation tend to find their creativity and labor appropriated without proper remuneration in the YouTube dance-video economy, which continues to “primarily benefit those with preexisting economic and cultural capital, whether brands, celebrities, or along lines of class and race” (Harlig 256).[20] YouTube is, after all, owned by Google.

How can the essentially social, kairotic, and mutually affirming queer experience of Ballez class exist in the vast, cruel, auto-play universe of YouTube? One issue is the translation of physical sociality itself: Ballez Classes at BAX incorporate interpersonal queer gestures like the butch nod, the knowing glance, and a circle of gender-expansive partnering that can’t be replicated in a lonely bedroom somewhere. Ballez class is, in person, a mutual performance. “It’s not a workout class, where you’re just doing a movement to feel it for yourself,” Pyle emphasizes: it’s a set of embodied, affective movements with and for the people in the studio with you. Krekel, who speaks fondly of sequences where traveling piqué turns culminate in high-fives and playful tag-outs with whichever dancer has been cheering you on, observes how Ballez class puts “way more emphasis on development of community in class — not on being perfect, appeasing a teacher,” or competing with other dancers (Krekel). Furthermore, Pyle considers their teaching a performance in its own right — they know in advance which jokes they’ll tell, what the playlist will be, when to throw in an allusion to glitter or leather — and they plan time in class for participants to “stand back and watch each other” move, so that every dancer has an admiring audience. If Ballez class at BAX is a round dance at a village fête, in other words, how do you make dances for an ever-expanding circle of villagers on the internet?

For all of these reasons, the Ballez community has needed to be extremely creative in adapting queer sociality for digital publics. For example, during Ballez classes at BAX, dancers don’t use the wall mirrors, because there is an emphasis on dancers mirroring each other — on literally being seen (Mannino). Krekel calls this a “listening skill,” highlighting the mutual benefits of “looking at my fellow dancers and really admiring how they move” (Krekel). Being able to witness dancers whose virtuosity is not “tied to technical tricks” or measured by white cisheteronormative standards is, for Krekel, as important as being seen herself. In BCE YouTube videos, therefore, Pyle gives instructions such as, “You can imagine that there are mermaids swimming underneath you [. . .] and you’re going to reveal your inner ankle to the mermaids” (Ballez, “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 4: tendu”). When there aren’t mermaids watching you — for example, in the classic Ballez exercise “dégagés + butch nod” — Pyle looks directly at the camera and explains how, while you’re doing the dégagés to the front, you can cruise the people you’re with or the screen itself. In order to navigate the strange, simultaneous space of performing queer sociality for an unknowable audience, Ballez invokes the slightly unruly, carnivalesque atmosphere of the “village fête.” Part idealized lesbian bar, part Coney Island Mermaid Parade, and part restaging of an Indulgence party at Casa La Femme, Ballez Class Everywhere creates a flexible, improvisatory queer fantasy space populated by beings whose hybrid or dematerialized embodiments do not prohibit them from dancing with you.

When the first Ballez Class Everywhere video was posted on YouTube on April 8, 2019, Pyle felt the strange emptiness of performing without an audience: no applause, no curtain call, no emotional surge from standing sweaty under the hot lights with all of your fellow dancers. The temporality of YouTube production is isolating, whether it produces the time-lagged feeling of a non-event or the unnerving explosion of sudden viral popularity. Moreover, as Harmony Bench notes in a study of “gay” re-performances of Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” choreography, there is a particular risk for queer or gender-nonconforming dancers who expose themselves “to the scrutiny of viewers outside their affective communities” through online videos; “many are berated for failing to appropriately perform the gendered behaviors assigned to their sex [. . .] and for dancing in a way that online commentators designate as gay or queer” (“Single Ladies” 147).[21] Although the “comment” function is disabled on Ballez’s YouTube channel, it is still possible to “like” or “dislike” a video. It is a great relief to find, therefore, that approximately one year after the first BCE video was posted, it has been viewed more than 4,000 times; there are seventy-nine “likes” and zero “dislikes”; 549 people have subscribed to the Ballez channel, which YouTube groups with other instructional-dance videos for basic ballet. It appears that not only are people stretching and dancing with Ballez as a digital community, they are also expanding the community across geographical space.

In Pyle’s home-made effort to wrench ballet out of its exclusionary history for people like Ely in Sioux Falls, they also made it exponentially more accessible. Once Pyle had done the closed captioning, for example, the YouTube videos could be accessed in more than eighty languages. (As Pyle pointed out to me, this is seventy-nine more languages than they can personally teach class in.) Ballez Class Everywhere is composed of thirteen short “episodes” organized as a playlist, allowing participants to slow the speed of the videos, watch them repeatedly, pause when they need to, or adapt the order of turns and jumps to suit their mobility and spatial constraints. BCE as a digital object lends itself to a wide range of modalities, offering a flexibility that would be impossible for any in-person dance class held in a studio.

Moreover, if a ballet student of any gender or sexuality, anywhere in the world, is searching YouTube to learn how to do a tendu properly, the chances are now much higher that a Ballez video will pop up in their feed. And if that happens, those young dancers will learn tendus from a vastly more inclusive queer perspective. Tendu is the French word for “extended,” and it is related to what is held, what is rigid and tense, what is stretched all the way to its limit. Extension through the legs is an important metric of traditional balletic virtuosity, and dancers are often judged on how much their limbs can extend to meet idealized lines of bodily form. But when Pyle teaches the tendu, they emphasize its etymological relation to “tenderness,” defining it as gently “extending your heart to someone” (“Ballez Class Everywhere no. 4: tendu”). The position of the foot becomes playful and sexy; Pyle explicitly reminds BCE participants of the expressive, lively, and erotic impulses that underlie courtly ballet, despite its attempts to codify and suppress sensuality. The position of the arms helps dancers to “connect to your heart” and then, Pyle urges, to “extend tenderness — could be glitter, could be roses, could be magic — to everyone else in our queer court.” In the first minute of teaching the tendu, Ballez Class Everywhere has queered the position’s linguistic origins, debunked the courtly masking of ‘low’ desires, reframed ballet steps as exercises in generosity and elasticity, inverted the careful social order ballet has sought to preserve, and showered this newly imagined queer village with glitter.

Both the searchability and the linguistic accessibility of captioned Ballez videos belong to a strategy that Pyle thinks of as “infiltration.” Tactically, infiltration is a virtual mode of “seep[ing] in,” as Pyle explained to me: to use the uneven amplifications of social media to put tiny queer tendrils into mainstream ballet culture. Infiltration is why Pyle uses Kickstarter not only to fundraise, but also to disseminate the Ballez logo as widely as possible. Ballez tote bags, Ballez T-shirts, Ballez stickers, retro Ballez iron-on embroidered patches: these are not so much rampant acquisitional accessorizing as they are a kind of latter-day hankie code. Imagine, Pyle exclaimed to me, if all over the world “young dancers could walk into their studio with an embroidered Ballez workman’s shirt,” signaling that cisheteronormative assumptions about their bodies need not apply.

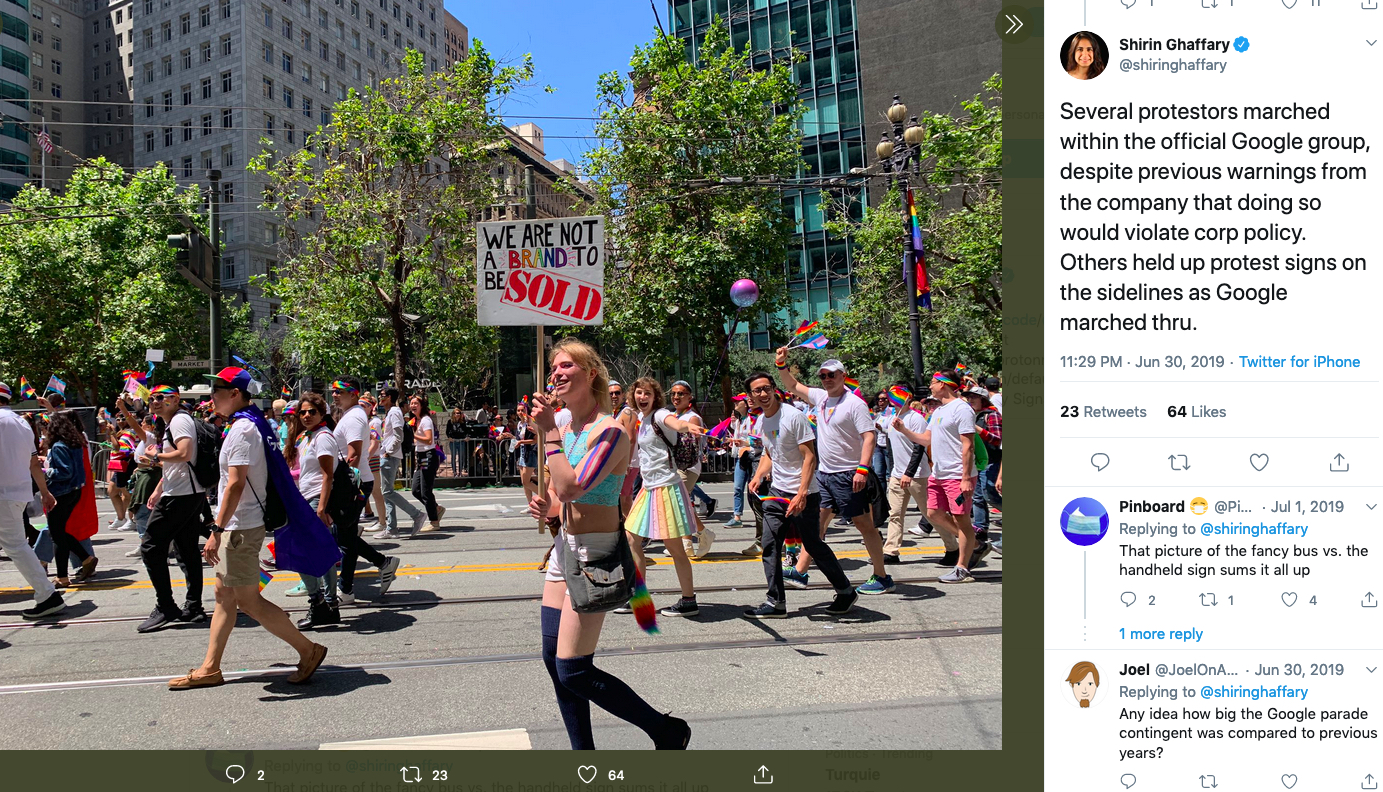

This kind of communal queer signifying is especially poignant in contrast to the corporate rainbow virtue-signaling that happens around Pride. There is a stark difference between a talisman that helps queer and trans dancers create safe spaces for their bodies and a marketing campaign that uses bland happy rainbow language about love, for a month, to sell things. This is why, during the 2019 San Francisco Pride Parade, a group of Google employees were so troubled by the corporation’s unwillingness to protect LGBTQ+ people from harassment on YouTube that they marched as a “Resistance Contingent” in protest of their employer (Ghaffary, “Here’s why Google workers plan to protest”). Google, an official sponsor of SF Pride, warned these employees that they were not allowed to voice their concerns if they marched with the Google float; this would constitute a violation of Google’s code of conduct. Understandably bewildered and outraged, the protesters asked two quite reasonable questions: where is the code of conduct that protects the LGBTQ+ community from hate speech on YouTube? And why does YouTube’s much-vaunted free speech policy protect homophobic rants but not us? Google didn’t answer. It didn’t have to. The SF Pride Board of Directors denied the request to forgo Google’s sponsorship, and on the day of the Parade, the open-top Google bus rolled down Market St., emblazoned with “Pride Forever,” while crowds of bright Google-branded superhero capes and rainbow flags fluttered around it. A small band of protestors marched stubbornly alongside them; someone with a trans pride flag painted on one arm held up a hand-drawn sign that read, “We are not a brand to be sold.” A Vox journalist posted the image to Twitter (Ghaffary).

Several protestors marched within the official Google group.[22]

These moments of infiltration exemplify the potential as well as constraints for queer and trans communities enmeshed in social media. The behemoths of brands offer a platform, visibility, and the possibility of outreach; at the same time, these corporate entities uphold practices of discrimination, harassment, and exclusion that damage communities. Thus, the tiny brigades of internal resistance must navigate the paradox of free, flexible, on-demand connection facilitated by institutions whose idea of ‘equity’ has everything to do with investment capital, and almost nothing to do with justice. In the field of ballet, this struggle was made manifest by the ABT brand ambassador himself, Alexei Ratmansky, who wrote a Facebook post in 2017 proclaiming that “there is no such thing as equality in ballet: women dance on point, men lift and support women. women receive flowers, men escort women off stage. not the other way around [. . .] and I am very comfortable with that.” In real life, Ratmansky is exactly the kind of powerful, well-funded man in the aristocracy of ballet who doesn’t have to listen to Pyle. But Pyle, responding to Ratmansky on Facebook, wrote with barely restrained queer fury, “Wow if you are the future of ballet I hope it dies” — and, this being Facebook, Ratmansky felt compelled to write back. This exchange, like a four-minute Ballez Class Everywhere video showing queer, consent-based partnering in adagio, is a tiny flicker of hope. It’s not that Facebook and YouTube are inherently democratic or inclusive; it’s that Pyle is figuring out how to queerly infiltrate dominant ballet culture by queerly infiltrating mainstream social media.

The Ballez class slogan “We’ll see you at the barre!” is a lesbian ballet pun that cannot help but allude to the fact that lesbian bars have been disappearing steadily from urban landscapes for decades. A spate of recent articles with titles like “The Demise of Queer Space?” (Doan and Higgens) and “There Goes the Gayborhood” (Brown) give a sense of diminishing, doomed, crumbling queer geographies. We know from scholars of lesbian geography, like Kath Browne and Japonica Brown-Saracino, as well as from Petra L. Doan’s work on trans belonging in urban space, that lesbian, trans, and gender-nonconforming people are marginalized even within broader ‘queer’ spaces, especially in relation to cis gay men. Ballez class in Brooklyn,[23] therefore, has provided a lesbian-centered space in an increasingly hollow and sparse geography; there were more lesbian bars in New York City in the 1930s than in 2021 (Carmel).[24]

In Jen Jack Gieseking’s study “Dyked New York,” which surveyed the city’s lesbian geographies from 1983-2008, there is an interesting tension between the very real disappearance of a certain number of lesbian bars and the disproportionate, intensely nostalgic attachment to what lesbians and queer women imagine the significance of these bars to have been. Gieseking calls this “a deep sense of nostalgia for that ideal socially inclusive, politically astute and economically accessible space that always seems to be lost” (35). In an elegy for San Francisco’s Lexington Club, Gayle Salamon writes, “The Lex was living room and organizing hall and art gallery and stage set” (147); Nikki Lane notes that “the metaphor of ‘home’ figures prominently across my informal and formal interviews with BQW [Black queer women] in Washington DC” (231).[25] It seems that the lesbian bar is a site of queer sociality so ideal — so elastically inclusive — that it has only ever existed as a referent of the desire for a place where, for example, you could find the cool butch nod and the melty femme fondu of feelings.

The dyke bars that disappeared from urban landscapes have prompted lesbian communities to creatively honor their ghosts. Elegies, archival projects, activist walking tours, documentaries, and even a musical called Alleged Lesbian Activities: in her ethnography of “dyke bar commemoration,” Japonica Brown-Saracino emphasizes “how memory can be future-oriented” when lesbian nostalgia is tapped as a source of potential “reparative action” (4).[26] Strikingly, Brown-Saracino finds that commemorations of vanished lesbian bars — which critique the bars’ histories of racism and transphobia, as well as celebrating their “association with community and collective identity” — become inclusive, community-building events in themselves (4). In other words, the loss of lesbian bars incites the creation of a new kind of lesbian social space. Seeking to recover the mythical moment of the lesbian bar, with all its exclusions and imperfections, small groups like the Dyke Bar Takeover Collective (NYC) and the Lexington Archival Project (SF) return to the past and perform it anew for their communities. And yet, Brown-Saracino notes with some surprise, dyke-bar commemorators do not seem to want new lesbian bars where they could gather: “Instead, they desire mobile ‘social space’ characterized by the inclusion of queer individuals of diverse racial, gender, and age backgrounds. And increasingly, they seek to set the stage for a future in which disparate individuals come together without the bar as anchor” (11-12, emphasis added). Brown-Saracino attributes the longing for this particular queer future to three factors: technologies that transcend “local networks”; the unstoppable gentrification of neighborhoods that once supported lesbian bars; and a belief that inclusivity must extend beyond the local (12). In short, Ballez Class Everywhere is the new lesbian bar.

This is why “We’ll see you at the barre!” is not just another bad ballet pun; it is Pyle’s vision of Ballez class as an inclusive, elastic, and “mobile ‘social space’” that commemorates ballet’s complicated history in the service of queer utopian futurity. And, in fact, Pyle, a staunch believer in the ethics of old-school, DIY lesbian sociality, does not ultimately intend for Ballez Class Everywhere to succumb to the dispersed, disposable, disembodied affect that so often becomes the default of digital culture. Rather, Pyle told me that they use social media only and “always in order to get people to come do things in person.” They see the Ballez Class Everywhere videos not only as a form of infiltration of lesbian sociality into the lives of isolated queer and trans dancers, but also as a way to stretch those people towards each other, in real life, in places beyond New York City. “It’s not up to me,” Pyle told me, “but I hope people don’t just do them alone and stay alone forever.” This desire for queer communities to congregate in person is a DIY translation of digital space back into a re-centered lesbian sociality. Pyle wants people to gather in parks, in laundromats, in otherwise cisheteronormative ballet studios, and at house parties and village fêtes, so that when Ballez Class goes everywhere, we are doing it together.

This line is doubly indebted to Julian Carter’s SEX TIME MACHINE For Touching the Transcestors (2018) and to Katy Pyle’s “Foreword” in the anthology (Re:) Claiming Ballet, which proposes that we not only need to recover the histories that ballet has suppressed, but also to become “good ‘dancestors’” for those who follow in our footsteps” (x). ↑

In modern dance, San-Francisco-based trans choreographer Sean Dorsey has been at the forefront of offering “trans-positive” classes, workshops, and community activities for people of all ages and abilities. ↑

A notable exception is Les Ballets Trockadero de Monte Carlo. Founded in 1974, the Trockadero combined a fervent love of ballet with a drag rebellion against its outdated prescriptions for gender and sexuality. They believed that neglected elements of ballet history were worth saving; moreover, they assumed that a professional ballet company could be as diverse as a healthy neighborhood in New York City (Schwartz 131). One of the most astonishing accomplishments of the Trockadero has been to stretch the form of ballet across the spectrum of gender: every company member can perform both male and female roles. For more than forty years, on tours that span the globe, the drag ballerinas of the Trockadero have embodied this ethos of inclusivity, with a focus on gay men of various races, sizes, national origins, ages, and gender presentations. Although one dancer, Chase Johnsey, claimed in 2018 that he had experienced discrimination and harassment based on his gender presentation, an independent investigation involving twenty-four witnesses did not substantiate those claims (Thompson). More recently, Maxfield Haynes, a non-binary dancer who notes, “it’s not common for somebody who is so unapologetically queer, so unapologetically black, to be so successful in the dance industry,” has praised the Trockadero for having “always accepted everything about me,” stating that they felt “lucky” to have worked with the company (LaRoche). When Alby Sabrina Pretto, a trans ballerina who has danced with the Trockadero for eight years, decided that it was time for her to physically transition, the company publicly affirmed that she could keep her job if she wanted it (Scher, “For transgender dancers”). ↑

This resonates with Noe Montez’s observation that “queer spaces are rife with embodied pedagogy, what Marlon Bailey describes in his study of ball culture as ‘kin labor,’ which transmits intergenerational knowledge that is life-giving and life-saving for those alienated by racist cisheteropatriarchal systems” (x). ↑

See, for example, Saidiya Hartman’s Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), and Gayle Salamon’s The Life and Death of Latisha King: A Critical Phenomenology of Transphobia (2018). ↑

See, for example, the anthology (Re:) Claiming Ballet, edited by Adesola Akinleye, in which she “calls for a decolonization of ballet by recognizing a fuller contribution to the artform than the narrow exclusively White, straight male persona that is recognizable as destructively and distractively dominant in mainstream constructs of what ballet can achieve” (1). ↑

“Reconsidering which bodies ‘begin’ the medium of ballet also invites new genealogies of performance analysis, asking how ballet performs and maintains normative notions of the body,” Preston observes (227). Preston makes persuasive claims for the value of telling ballet’s “history from below”; we might also consider who is allowed to tell this history authoritatively (14). In the case of elite cultural forms like ballet that have so often been wielded to reinforce exclusions, it seems important to center the voices of those who have not been permitted to claim its history. ↑

In the opening pages of After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life, Joshua Chambers-Letson draws on Fred Moten’s vision of a house party “of and for the dispossessed” to theorize the party as “as much a site of refuge as it is the site of revolutionary planning,” particularly for queer people of color (xi). ↑

As Noe Montez writes, “the redirection of queer studies toward politics of hope and futurity imbue it with the task of dreaming, and dreaming particularly through performance” (xi). ↑

Part of this virtuosity, Pyle explained to me, is a queer skill of adjusting gender expression and affect, depending on how risky or welcoming the context appears to be. Unless otherwise noted, all quotes and paraphrases from Katy Pyle are from the personal interview conducted on May 14, 2019. ↑

Ahmed argues against sentimental futurity, but she holds out hope, “because what is behind us is also what allows other ways of gathering in time and space” (179). ↑

The Firebird, a Ballez premiered at Danspace Project, St. Mark’s Church in New York, May 16-18, 2013. For an analysis of this piece, see Gretchen Alterowitz’s “Embodying a Queer Worldview: The Contemporary Ballets of Katy Pyle and Deborah Lohse”; Eva Yaa Asantewaa’s review praises the space that this piece “make[s] for ballet to contain imperfection and feeling by reeling it back from mechanical exactitude and just plain giving it to the people,” while New York Times dance critic Gia Kourlas found that it “blazes with heart” but “needs a more rigorous approach in terms of ballet technique and performance style.” ↑

Sleeping Beauty & the Beast premiered at La Mama Moves! Dance Festival, New York, April 29-May 8, 2016. For an account of dancing in this piece (and challenging the reviews it received in mainstream press outlets), see Janet Werther’s “Ballez Talks Back”; for an analysis of selected scenes, see my book The Bodies of Others (157-163). ↑

For example, when dance student Alexandra Waterbury came forward in 2018 to call out a misogynist culture at NYCB — building on the testimony of five dancers who had been abused by Peter Martins and twenty-four more who corroborated claims of a hostile and unfair work environment under his direction — she named three principal male dancers who had circulated sexually explicit images, accompanied by demeaning language (Pogrebin and Cooper). It came out that a board member of NYCB had proposed, by text, the idea of raping female dancers. Eventually, NYCB was acquitted on the grounds that Waterbury had not been a student or employee of the company at that time; two of the three perpetrators were invited back as principal dancers; the New York Times reported that fundraising was virtually unaffected (Pogrebin and Cooper). Among others, Katy Pyle spoke out in support of Waterbury, stating, “The history of ballet is intertwined with that of the capitalist cis hetero patriarchy, which has allowed for women to be used and abused, as the property and playthings of men with power” (Stahl). In Pyle’s view, Waterbury was just one more example of the ways in which “the traditions of silencing women [. . .] continue today in the ‘top’ (aka most funded) ballet institutions of the Western world.” In a classical ballet world in which, as dance historian Lynn Garafola put it, powerful men like Peter Martins face “no punishment and no accountability” despite years of abusing multiple dancers, it is perhaps unsurprising that Alexandra Waterbury now dances with Ballez (Villarreal). ↑

For more information on these vanished lesbian bars and parties, see Gwen Shockey’s “The Addresses Project,” an interactive historical map of lesbian and queer spaces in New York City that is funded in part by the Dyke Bar Takeover Collective. According to Shockey, Fem 2 Fem at The Roxy was located at 515 West 18th St from 1979-2007, an address that now turns up on Google as “Luxury West Chelsea Condos for Sale.” Indulgence at Casa La Femme was a party thrown by Wanda Acosta in 1993 at 150 Wooster St.; Shockey reported in early 2018 that the building was vacant, but later that year a penthouse at that address sold for $32.6 million, reportedly “the second most expensive unit to sell in the city thus far in 2018” (Pitt). The Apple store in Soho is located at 103 Prince St., around the block. In an interview in 2019, Gwen Shockey mentioned that Wanda Acosta has begun throwing parties again — “warm and sexy. And super diverse” — providing a rare note of hope in a generally bleak landscape for lesbian nightlife in NYC (Wennerholm 72). ↑

For an overview of dance organizations in New York City that are adopting land acknowledgements and working to be more inclusive of Indigenous artists, see Siobhan Burke’s “On This Land: Dance Presenters Honor Manhattan’s First Inhabitants.” ↑

Pyle’s extremely modest scale for community funding reflects a double bind: how can you ask your communities for the money you need to create community-oriented projects, when your communities are also under-resourced? In research on trans communities using YouTube, Tobias Raun has found that “trans vloggers have been — and often still are — reluctant to monetize their content,” in large part because of an ethical sense, a ‘duty’ to give back to the community (“Capitalizing Intimacy” 103). At the same time, it has been well-documented that lesbian income levels are below those of gay men, leading to “gayborhoods” that “can exclude lesbians spatially by out-pricing rents and mortgages” (Brown 459), a gentrification process that also disproportionately affects people of color, trans people, gender-nonconforming people, and bisexual people (Doan and Higgens 8). ↑

According to Katy Pyle, of the nine dancers who participated, seven are white, one is Black, and one is Afro-Latino; they use a range of gender pronouns. In the Kickstarter video, dancers describe themselves with phrases such as, “I’m not the traditional ballerina,” or identify mainstream ballet as entailing “sexist roles that I have to dance” and “a really white-washed scene.” ↑

Bench concludes, “I find that social dance-media projects specifically amplify the popular and social aspects of dance, reimagining the sociality of dance practices of and for a digital era” (“Screendance 2.0” 206). ↑

Alexandra Harlig’s 2019 dissertation, which includes a chapter devoted to “Studio Class Videos as an Emergent Internet Screendance Genre,” details the gap between the massive popularity of dance videos on YouTube and the miniscule amount of compensation their creators receive. For a more celebratory reading of “enabling the YouTube archive to facilitate counterpublics” in dance, see Kristen Pullen’s “If Ya Liked It, Then You Shoulda Made a Video: Beyoncé Knowles, YouTube and the public sphere of images” (147). ↑

In addition, feminist media scholars report that not only are women (and presumably also people perceived to be women) under-represented on the most-subscribed YouTube channels, but those few women are also disproportionately subject to gender-based “harshly critical or sexually-aggressive” responses from viewers (Wotanis and McMillan 924). ↑

https://twitter.com/shiringhaffary/status/1145444154387787776. Accessed 16 April 2021. ↑

BAX is located in Park Slope, which has an interesting history of gentrification. As Judith R. Halasz reports, “Census data confirm that Park Slope met the conditions of gentrification by 1990 [. . .] But it was not yet an exclusive neighborhood. Many working-class Irish American, Italian American, African American, and Latino families” continued to reside there for the following decade; by 2014, however, “all sections of the neighborhood met 100% of the necessary conditions of supergentrification” (1378, 1381). Founded in 1991 in Gowanus, BAX moved into Park Slope in 1998; its website states that the organization is currently “actively engaged in challenging the manifestations of whiteness, able-bodiedness, and privilege as part of our ongoing anti-racist efforts and our other anti-oppression, pro-inclusion work.” Unlike the DEI statement put forth by NYCB, which emphasizes “focus groups” and an unspecified “formal process to make diversity, equity, inclusion, and anti-racism a priority at NYCB,” the BAX “Accountability and Action” statement includes concrete efforts such as fundraising for Black Trans Femmes in the Arts Collective, publicly calling on local officials to divest from the NYPD, and redirecting funding received from the Wallace Foundation to support BLM protests. ↑

As of spring 2021, journalist Julia Carmel counted three: Henrietta Hudson and Cubbyhole in Manhattan’s West Village, and Ginger’s Bar in Park Slope, Brooklyn, which closed “indefinitely” during the pandemic. ↑

Lane’s ethnography makes a strong argument that Black queer women tend not to feel fully at home in white lesbian spaces or in spaces oriented towards black heterosexual women (226), and that lesbian geography as a field has been lacking in intersectional approaches that account for racialized experiences (236). ↑

Performance theorist Tavia Nyongo’o, drawing on feminist theater scholar Sue-Ellen Case’s characterization of the current era as “the Great Upload,” argues eloquently that “our political imaginations must find their orientation not beyond but within its dynamic, guarding against any nostalgia for the historical foundations. History marches on, but glitter sticks in the floorboards” (47). ↑

Acone, Ludmila. “Entre Mars et Vénus. Le genre de la danse en Italie au xv siècle.” Translated by Susan Emanuel. Clio: Women, Gender, History, vol. 2, no. 46, 2017, pp. 135-148.

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press, 2006.

Akinleye, Adesola. “Introduction: Regarding claiming ballet / reclaiming ballet.” (Re:) Claiming Ballet, edited by Adesola Akinleye, Intellect, 2021, pp. 1-8.

Alterowitz, Gretchen. “Embodying a Queer Worldview: The Contemporary Ballets of Katy Pyle and Deborah Lohse.” Dance Chronicle, vol. 37, no. 3, 2014, pp. 335-366. https:/doi.org/10.1080/01472526.2014.957599.

Asantewaa, Eva Yaa. “‘The Firebird, A Ballez’ at Danspace Project.” Infinite Body, blog. 18 May 2013. https://infinitebody.blogspot.com/2013/05/the-firebird-ballez-at-danspace-project.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Assunção, Muri. “Last Call for Lesbian Bars: The Ever-changing Nightlife for LGBTQ women in New York.” New York Daily News, 19 March 2019. https://nydailynews.com/new-york/ny-lesbians-queer-women-bars-nightclubs-new-york-history-20190519-dvbvom7rwrcpllr7pg3o74aec4-story.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Ballez Company/Katy Pyle. “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 3: pliés.” 9 April 2019. https://youtu.be/fd5au7dSOVc.. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 4: tendu.” 8 April 2019. https://youtu.be/jqMAL-9wzVo. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 5: dégagés + butch nod.” 22 April 2019. https://youtu.be/_qI38R4v7FQ. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Ballez Class Everywhere no. 6: fondu + rond de jambe.” 22 April 2019. https://youtu.be/fv6_glCp_gI. Accessed 16 April 2021.

BAX [Brooklyn Arts Exchange]. “About Us.” https://bax.org/homepage/about-us/. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Bench, Harmony. “‘Single Ladies’ is Gay: Queer Performances and Mediated Masculinities on YouTube.” Dance on Its Own Terms: Histories and Methodologies, edited by Melanie Bales and Karen Eliot, Oxford Scholarship Online, 2013. https:/doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199939985.003.0007

———. “Screendance 2.0: Social Dance-Media.” Participations: Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, vol. 7, no. 2, 2010, pp. 183-214.

Brown, Michael. “Gender and sexuality II: There Goes the Gayborhood.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 38, no. 3, 2014, pp. 457-465.

Brown-Saracino, Japonica. “From Situated Space to Social Space: Dyke Bar Commemoration as Reparative Action.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 24, no. 3, 2019.

———. “From the Lesbian Ghetto to Ambient Community: The Perceived Costs and Benefits of Integration for Community.” Social Problems, vol. 58, no. 3, 2011, pp. 361-388.

Brown-Saracino, Japonica, and Jeffrey Nathaniel Parker. “‘What Is up with My Sisters? Where Are You?’ The Origins and Consequences of Lesbian-Friendly Place Reputations for LBQ Migrants.” Sexualities, vol. 20, no. 7, Oct. 2017, pp. 835–874. https:/doi.org/10.1177/1363460716658407.

Browne, Kath. “Lesbian Geographies.” Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 8, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-7.

Burke, Siobhan. “On This Land: Dance Presenters Honor Manhattan’s First Inhabitants.” New York Times, 2 August 2018. https:/nytimes.com/2018/08/01/arts/dance/indigenous-land-performing-arts-theaters.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Carmel, Julia. “How Are There Only Three Lesbian Bars in New York City?” New York Times, 16 April 2021. https://nytimes.com/2021/04/15/nyregion/lesbian-bars-new-york-city.html. Accessed 17 April 2021.

Carter, Julian B. “Chasing Feathers: Jérôme Bel, Swan Lake, and the Alternative Futures of Re-Enacted Dance.” Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings, edited by Clare Croft, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 109-124.

———. “SEX TIME MACHINE for Touching the Trancestors.” Out/Look and the Birth of the Queer, Sex Time Machine 3.0, 2018. http:/queeroutlook.org/portfolio/julian-carter. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Chambers-Letson, Joshua. After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life. New York University Press, 2018.

Christian, Aymar Jean. “Camp 2.0: A Queer Performance of the Personal.” Communication, Culture & Critique, vol. 3, 2010, pp. 352–376. https:/doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-9137.2010.01075.x.

Croft, Clare. “Dancing toward Queer Horizons.” Theatre Topics, vol. 26, no. 1, March 2016, pp. 57-62. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2016.0000.

———. “Introduction.” Queer Dance: Meanings and Makings, edited by Clare Croft, Oxford University Press, 2017, pp. 1-33.

Doan, Petra L. “Queers in the American City: Transgendered Perceptions of Urban Space.” Gender, Place & Culture: A Journal of Feminist Geography, vol. 14, no. 1, 2007, pp. 57-74.

Dolan, Jill. Utopia in Performance: Finding Hope at the Theater. University of Michigan Press, 2005.

Doan, Petra L., and Harrison Higgins. “The Demise of Queer Space? Resurgent Gentrification and the Assimilation of LGBT Neighborhoods.” Journal of Planning Education and Research, vol. 31, no. 1, 2011, pp. 6-25.

Eckstein, Ace J. “Out of Sync: Complex Temporality in Transgender Men’s YouTube Transition Channels.” QED: A Journal in GLBTQ Worldmaking, vol. 5, no. 1, 2018, pp. 24-44.

Gal, Noam, Limor Shifman, and Zohar Kampf. “‘It Gets Better’: Internet Memes and the Construction of a Collective Identity.” New Media & Society, vol. 18, no. 8, 2016, pp. 1698-1714.

Gaunt, Kyra D. “YouTube, Twerking & You: Context Collapse and the Handheld Co-Presence of Black Girls and Miley Cyrus.” Journal of Popular Music Studies, vol. 27, no. 3, 2015, pp. 244-273.

Ghaffary, Shirin. “Here’s why Google workers plan to protest their employer at Pride Parade this weekend.” Vox. 28 June 2019. http:/vox.com/recode/2019/6/28/19303292/google-protest-pride-parade-lgbtq-youtube-harassment. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Several protestors marched within the official Google group.” @shiringhaffary Twitter, 30 June 2019. https://twitter.com/shiringhaffary/status/1145444154387787776. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Gieseking, Jen Jack. “The Space between Geographical Imagination and Materialization of Lesbian-Queer Bars and Neighborhoods.” The Routledge Research Companion to Geographies of Sex and Sexuality, edited by Gavin Brown and Kath Browne, Routledge, 2016, pp. 29-36.

Goldmacher, Shane. “How David Koch and his Brother Shaped American Politics.” New York Times, 23 Aug. 2019. https://nyti.ms/2MypmFS. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Hafezi, l.n. “An Afternoon with the Ballez: Interview by l.n. Hafezi with Katy Pyle, Jules Skloot, Evvie Allison, Sam Greenleaf Miller, and Lindsay Reuter.” Helix Queer Performance Network. 1 May 2014. https://helixqpn.org/post/88567248392/an-afternoon-with-the-ballez. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Halasz, Judith R. “The Super-gentrification of Park Slope, Brooklyn.” Urban Geography, vol. 39, no. 9, 2018, pp. 1366-1390. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2018.1453454.

Hamera, Judith. Dancing Communities: Performance, Difference and Connection in the Global City. Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.

Harlig, Alexandra. “Social Texts, Social Audiences, Social Worlds: The Circulation of Popular Dance on YouTube.” PhD Dissertation, Ohio State University, 2019.

Horak, Laura. “Trans on YouTube: Intimacy, Visibility, Temporality.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 4, 2014, pp. 572-585. https://doi.org/10.1215/23289252-2815255.

Kourlas, Gia. “Trimming Stravinsky in Purple and Red.” New York Times, 17 May 2013. https://nytimes.com/2013/05/18/arts/dance/katy-pyles-firebird-a-ballez-at-danspace-project.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Kraut, Anthea. “Reenactment as Racialized Scandal.” The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Reenactment, edited by Mark Franko, Oxford Handbooks Online, 2017, pp. 356-374. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199314201.013.3.

Krekel, Madison. Personal interview (phone). 8 December 2020.

La MaMa Blogs. “Meet the Ballez!” 31 March 2016, La MaMa E.T.C. https://lamamablogs.blogspot.com/2016/03/meet-ballez.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Lane, Nikki. “All the Lesbians are White, All the Villages are Gay, but Some of Us are Brave: Intersectionality, Belonging, and Black Queer Women’s Scene Space in Washington DC.” Lesbian Geographies: Gender, Place and Power, edited by Kath Browne and Eduarda Ferreira, 2015, pp. 219-242.

LaRoche, Holly. “Maxfield Haynes and J. Bouey: Understanding your unique intersectionality.” Dance Informa, 28 June 2020. https://danceinforma.com/2020/06/28/maxfield-haynes-and-j-bouey-understanding-your-unique-intersectionality. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Ledford, Jayna. “Jayna Ledford on Her Journey as a Transgender Ballerina.” Dance Spirit, 20 September 2018. https://dancespirit.com/jay-ledford-trans-ballerina-2606526594.html Accessed 16 April 2021.

Lovelock, Michael. “‘Is Every YouTuber Going to Make a Coming Out Video Eventually?’: YouTube Celebrity Video Bloggers and Lesbian and Gay Identity.” Celebrity Studies, vol. 8, no. 1, 2017, pp. 87-103. https://doi.org/10.1080/19392397.2016.1214608.

Mannino, Trina. “The Future of Ballet Is Inclusive and Queer.” Vice, 9 August 2017. https://vice.com/en_us/article/9kk5k5/the-future-of-ballet-is-inclusive-and-queer. Accessed 16 April 2021.

McBean, Sam. “Remediating Affect: ‘Luclyn’ and Lesbian Intimacy on YouTube.” Journal of Lesbian Studies, vol. 18, no. 3, 2014, pp. 282-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/10894160.2014.896617.

Michaels, Cristina M. “Transphobia & Ballet.” Queer Dance Project, blog, 30 October 2020. https://queerdanceproject.com/2020/10/transphobia-ballet. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Michaels, Cristina M. “Queer Dance Project.” https://queerdanceproject.com/. Accessed 27 April 2021.

Montez, Noe, and Kareem Khubchandani. “A Note from the Editors: Queer Pedagogy in Theatre and Performance.” Theatre Topics, vol. 30, no. 2, July 2020, pp. ix-xvii. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2020.0026.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: The Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University Press, 2009.

NYCB [New York City Ballet]. “A Message from New York City Ballet.” https://nycballet.com/about-us/a-message-from-new-york-city-ballet. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Nyong’o, Tavia. “Period Rush: Affective Transfers in Recent Queer Art and Performance.” Theatre History Studies, vol. 28, 2008, pp. 42-48. https://doi.org/10.1353/ths.2008.0016.

Osterweis, Ariel. “Disciplining Black Swan, Animalizing Ambition.” The Oxford Handbook of Dance and the Popular Screen, edited by Melissa Blanco Borelli, Oxford Handbooks Online, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199897827.013.007.

Pitt, Amy. “Penthouse at Soho’s Boutique 150 Wooster Sells for $32.6m.” Curbed New York, 1 March 2018. https://ny.curbed.com/2017/12/6/16741948/soho-condo-sold-150-wooster-street. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Pogrebin, Robin, and Michael Cooper. “Vulgar Texts and Dancer Turmoil Force City Ballet to Look in the Mirror.” New York Times, 3 Oct 2018. https://nyti.ms/2P74Ytd. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Pryor, Jaclyn I. Time Slips: Queer Temporalities, Contemporary Performance, and the Hole of History. Northwestern University Press, 2017.

Pullen, Kirsten. “If Ya Liked It, Then You Shoulda Made a Video: Beyoncé Knowles, YouTube and the Public Sphere of Images.” Performance Research, vol. 16, no. 2, 2011, pp. 145-153. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2011.578846.

Pyle, Katy. “Adult Ballez Workshop.” Lewis Center for the Arts, Princeton University. 28 Feb 2016. https://arts.princeton.edu/events/adult-ballez-workshop-taught-katy-pyle. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Ballez.” https://ballez.org/. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Ballez Class Everywhere! Kickstarter.” Kickstarter, July-Aug 2017. Video by Courtney Powell. https://vimeo.com/224373730. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Foreword.” (Re:)Claiming Ballet, edited by Adesola Akinleye, Intellect Books, 2021, pp. vii-x.

—. Personal interview (Facetime). 14 May 2019.

Ratmansky, Alexei. “sorry, there is no such thing as equality in ballet” Facebook post. 17 Oct 2017. https://facebook.com/photo.php?fbid=10210201939469761&set=a.1133754148868.2020465.1377723438&type=3&theater. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Raun, Tobias. “Archiving the Wonders of Testosterone via YouTube.” TSQ: Transgender Studies Quarterly, vol. 2, no. 4, 2015, pp. 701-709.

———. “Capitalizing Intimacy: New Subcultural Forms of Micro-celebrity Strategies and Affective Labour on YouTube.” Convergence, vol. 24, no. 1, 2018, pp. 99-113.

Salamon, Gayle. Last Look at the Lex, Studies in Gender and Sexuality, vol. 16, no. 2, 2015, pp. 147-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/15240657.2015.1038203.

Schaefer, Brian. “At American Ballet Theater [sic], a Milestone and Momentum Forward.” Bloomberg, 20 Oct 2017. https://bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-20/at-american-ballet-theater-a-milestone-and-momentum-forward. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Scher, Avichai. “For Transgender Dancers, Change Can’t Come Fast Enough.” NBC News, 8 March 2020. https://nbcnews.com/feature/nbc-out/transgender-dancers-progress-can-t-come-fast-enough-n1147911. Accessed 16 April 2021.

———. “Pride & Dance: Why Our Field Can Be Both a Haven and a Challenge for LGBTQ Artists.” Dance Magazine. 28 June 2019. https://dancemagazine.com/lgbtq-dancers-2638993174.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Schwartz, Selby Wynn. The Bodies of Others: Drag Dances and Their Afterlives. University of Michigan Press, 2019.

Shockey, Gwen. “The Addresses Project.” 2016. https://addressesproject.com/map. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Sparti, Barbara. “The Function and Status of Dance in the Fifteenth-Century Italian Courts.” Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, vol. 14, no. 1, 1996, pp. 42-61.

Stahl, Jennifer. “Should Aspiring Ballet Dancers ‘Run in the Opposite Direction’?” Dance Magazine, 11 Sept 2018. https://dancemagazine.com/alexandra-waterbury-2602545003.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Thomas, Phillipa. “Single Ladies, Plural: Racism, Scandal, and ‘Authenticity’ Within the Multiplication and Circulation of Online Dance Discourses.” The Oxford Handbook of Dance and the Popular Screen, edited by Melissa Blanco Borelli, Oxford Handbooks Online. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199897827.013.019.

Thompson, Candice. “Updated: Chase Johnsey Talks About Those Allegations Against the Trocks.” Dance Magazine, 24 Jan 2018. https://dancemagazine.com/chase-johnsey-interview-trocks-allegations-2528105578.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Villareal, Alexandra. “‘It’s Like a Cult’: How Sexual Misconduct Permeates the World of Ballet.” The Guardian, 2 November 2018. https://theguardian.com/stage/2018/nov/02/ballet-stage-me-too-sexual-abuse-harassment. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Warnecke, Lauren. “For Queer Women in Ballet, There’s a Profound Gap in Representation. These Dancers Hope to Change That.” Pointe Magazine, 9 September 2020. https://pointemagazine.com/queer-women-in-ballet-2647537873.html. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Wennerholm, Zoe. “‘It’s your future, don’t miss it’: nostalgia, utopia, and desire in the New York lesbian bar.” BA Thesis, Vassar College, 2019. https://digitalwindow.vassar.edu/senior_capstone/897. Accessed 16 April 2021.

Werner, Ann. “Getting Bodied with Beyoncé on YouTube.” Mediated Youth Cultures: The Internet, Belonging and New Cultural Configurations, edited by Andy Bennet and Brady Robards, Palgrave MacMillan, 2014, pp. 182-196.

Werther, Janet. “Ballez Talks Back.” PAJ: Performing Arts Journal, 115, 2017, pp. 53-57. https://doi.org/10.1162/PAJJ_a_00351.