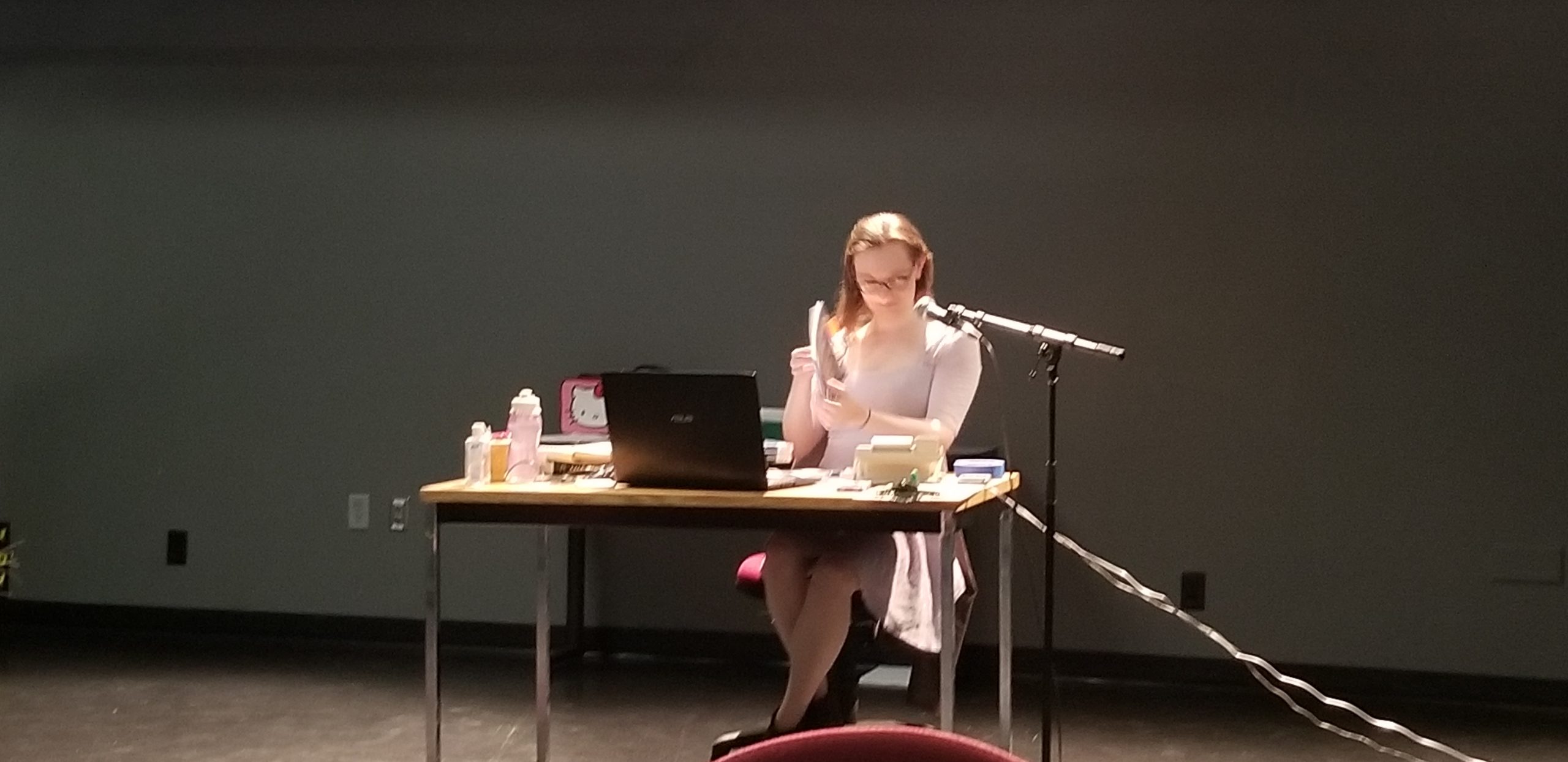

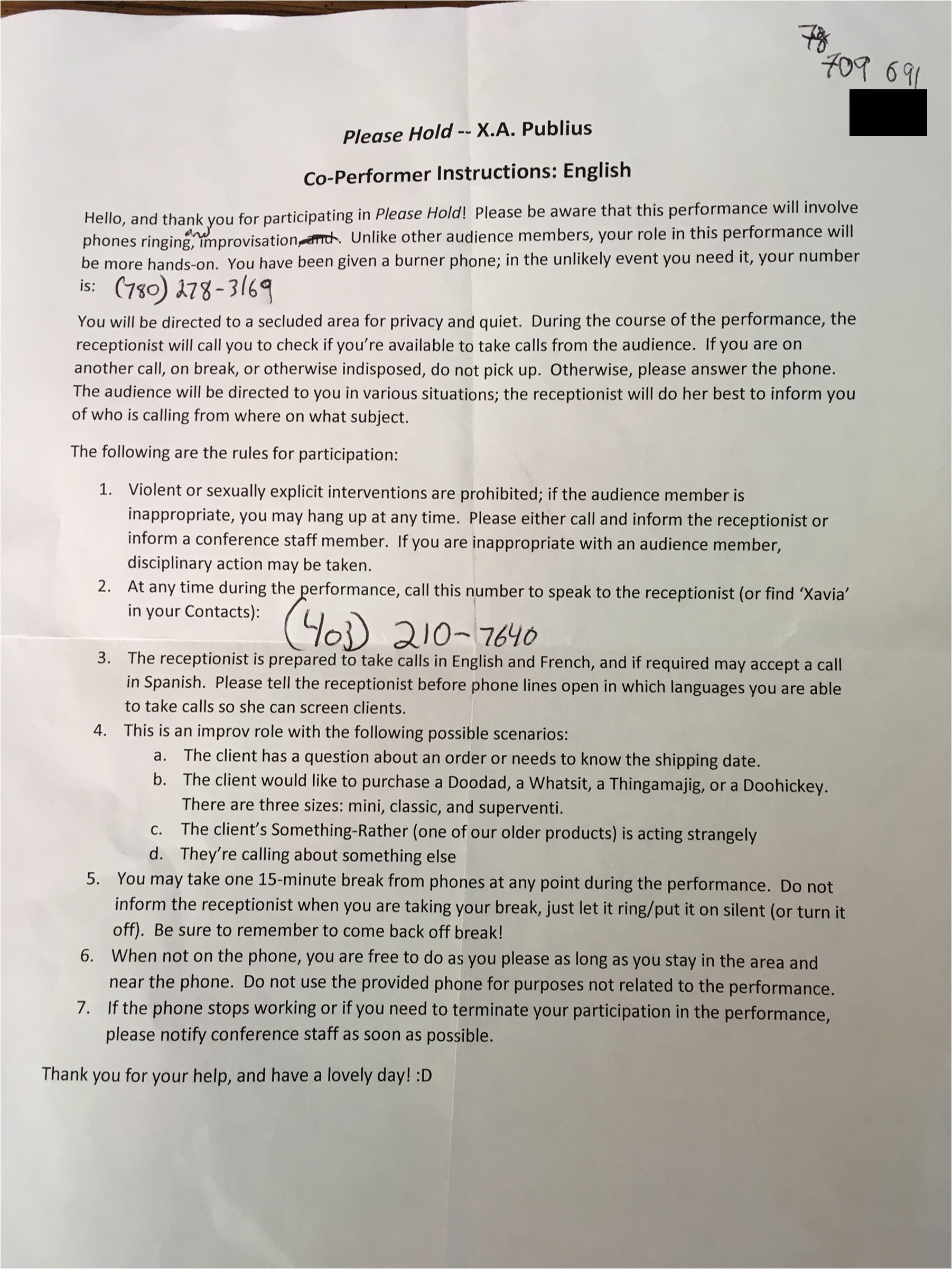

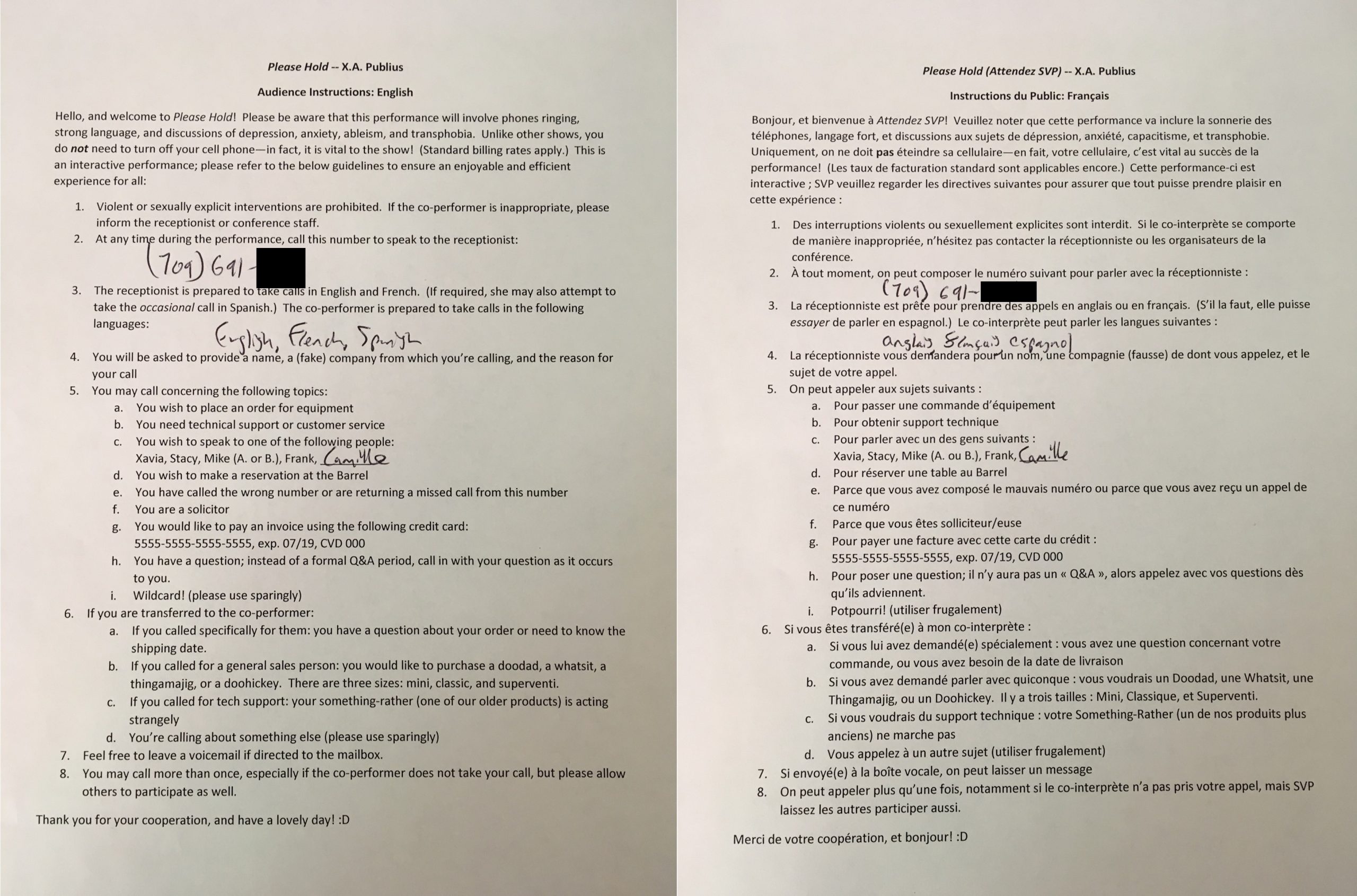

When I entered the playing space early-for-me Sunday morning at Performance Studies international (PSi) #25 in Calgary, I was slightly nervous. I had just finished the script of my presentation the night before, but I was confident I could pull this show off. I began setting up and consulted with the techs helping me, who showed me the office phone I had requested for the performance. The central conceit of Please Hold is that as I deliver my mystory about my experiences as a trans, neurodivergent receptionist and the emotional labour reception requires, the audience can call in from their cell phones and interrupt me. These calls are then redirected to my ‘Coworker,’ a co-performer selected from the audience prior to the beginning of the performance, who is tasked with addressing ‘customer’ concerns as they’re received. The Q&A aspect of the performance is also folded into this function.

This design replicates the constant task-switching, emotional regulation, and derailment I experience at my job by giving the audience the opportunity to disrupt the performance with fabricated sales calls. I had purchased a prepaid phone in my home city of Edmonton for the occasion, which would have allowed me to transfer the audience calls from the office phone to the Coworker, as intended. Unfortunately, when the office phone was hooked up, my attempts to call the prepaid phone were met with: “The call could not be completed as dialed.” My friend Telisa, who had worked as a receptionist for a decade, came over to help us out and noted that in older model office phones like the one I would be using, only the administrator phone could dial out long-distance; this meant that a core component of the work was unusable as envisioned.

Ironically, this logistical nightmare was the necessary failure to make the performance function effectively, as it resulted in the mental state I usually occupy at my job, where significant portions of my shift are frantic attempts to put out several fires at once. Reception necessitates a high degree of elasticity: pulling your smile so taut your emotions don’t leak out; bouncing from task to task before collapsing back into what you were working on five projects earlier; changing shape to accommodate the newest complication; stretching from coworker to coworker to client, in order to keep the peace and foster communication as the vital connective tissue holding things together on a daily basis. All without snapping. Thus, the mishap with the prepaid phone required me to channel the same problem-solving and emotional regulation skills that I access when phone lines go down at work. It also generated a narrative through-line to follow up on when no calls were waiting.

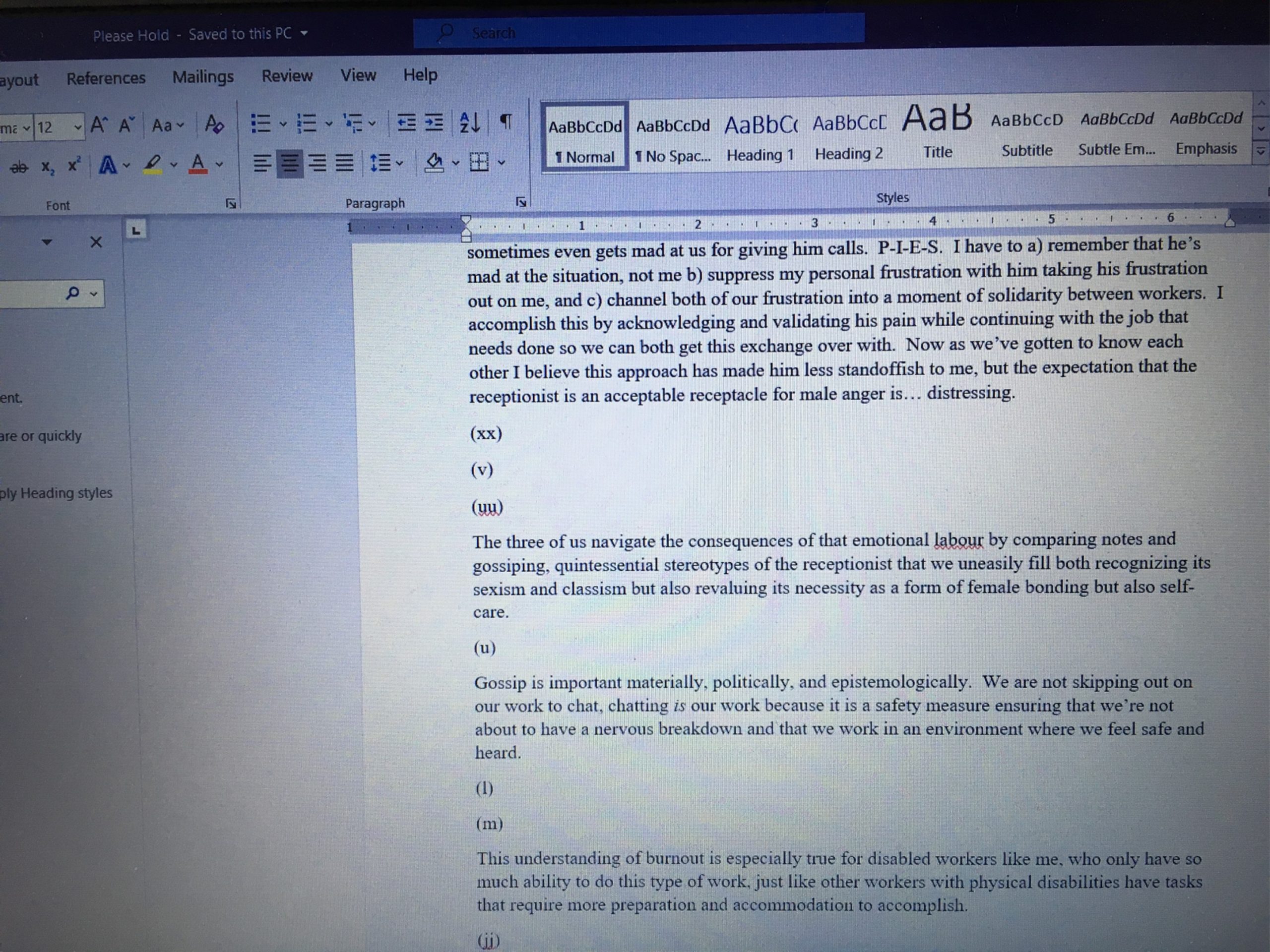

Because of its writing and production history, Please Hold is inextricably linked to its context as part of PSi #25. It was not just produced for this conference but was, in fact, a product of the conference, which gave it a poignance it would not have otherwise achieved. The script self-reflexively references the fact that it had to be written during the conference because of the very work it describes and lampoons:

I didn’t know what [this piece] was about until I got to this conference, because I had barely started writing it when the conference started. Part of this is who I am as a person and my executive dysfunction issues. But another part of it is that[,] ironically, I didn’t have time until this conference to write my experiences working, because I’ve been working. I am not physically capable of working [that many hours a] week, doing emotional and aesthetic labour and doing something that causes me even more anxiety than usual, and then coming home and doing my own work. I just can’t. [. . .] I quite honestly wasn’t sure I’d even have a piece today because instead of enjoying this conference I’ve had to use this brief oasis of time not centered around work to. . . do my work. [. . .] My life, my creative practice, my passion, is still on hold. (Publius, emphasis in original)

As such, Please Hold was not just a performance about the effects of emotional labour and neurodivergence; it was also a performance of those effects. This process also required (and allowed) me to adopt a more relaxed performance style — in the sense that the script was not memorized, it foregrounded and embraced imperfections, it promoted dialogue with the audience, and it could be cut easily.

As a mystory, the ‘script’ was actually three scripts. Michael and Ruth Bowman expand on Gregory Ulmer’s mystory structure — a portmanteau of ‘history,’ ‘mystery,’ and ‘my story’ — as a way to

establish a metonymic or allegorical relation between the self and the performance. Because the mystory is typically built as a collage or assemblage of textual/experiential fragments, and because it seeks to recode or reaccentuate those fragments intertextually or semiotically in the performance, the mystory performance becomes an occasion for inventing new knowledge of the self, rather than merely reproducing what is already known. (162)

Usually this is accomplished through weaving together three strands of discourse: professional, popular, and personal (165).

In Please Hold, these threads were my (personal) narrative framing the performance, readings of passages from major critical (professional) texts on emotional labour and reception — indicated in the script by letters in parentheses that corresponded to sticky notes in the books onstage — and a recording called “Receptionist Gothic,” which is a recitation of Tumblr-style (popular) gothic reframings of reception tropes loosely inspired by true events. By weaving these together with a performance strand (audience interventions), I hoped to create a multivalent exploration of life as a receptionist.

What this meant in performance was that there was far too much text, much of which had to be excised as I went along, focusing only on the highlights. Most of what I cut were the theoretical texts because ultimately my theoretical point wasn’t as immediately important as the emotional message expressed through my personal reflections. With a little more breathing room, in this essay I can point out that Arlie Hochschild’s foundational text on emotional labour, The Managed Heart, owes a great deal to performance theory:

What distinguishes theater from life is not illusion, which both have, need, and use. What distinguishes them is the honor accorded to illusion, the ease in knowing when an illusion is an illusion, and the consequences of its use in making feeling. In the theater, the illusion dies when the curtain falls, as the audience knew it would. In private life, its consequences are unpredictable and possibly fateful [. . .]. (48)

Hochschild uses Konstantin Stanislavski’s ideas about deep acting throughout her text to explain the emotional acrobatics workers in customer service, such as receptionists and flight attendants, must undergo to perform their job effectively (for instance, 44). As articulated in Please Hold, this means that between my two occupations

my life is not my own [. . .]. Admittedly, this conference is work I enjoy doing, but it is still work, and I am still performing. I am performing emotional labour right now, even as I frame this comment as a moment of ‘real’ emotion. [. . .] There is no strict dichotomy of depth and surface. My emotional state right now is political, but it’s also a product of me being fucking tired and frustrated and filled with existential dread.” (Publius)

Lest I be misunderstood, this critique is not about my employers or the conference, both of which were lovely and accommodating throughout the devising process; it is a commentary on the larger burdens of capitalism.

Receptionist Gothic, a series of miniature horror-comedy vignettes in the style of the Tumblr “X Gothic” meme. Recording and text by author.

Due to a separate technical issue with my audio equipment, the recording was primarily only brought into play about halfway through the performance when I needed to check out and have a panic attack under the table. I hadn’t planned on recreating that particular unprofessional workplace behaviour, but it happens at my job more often than I’d like. (Thankfully, my coworkers often take it in stride.) As with my performances of self in the workplace, this performance was not ‘fake’ — I really was shutting down — so much as it was stylized. At the conference, as is the case in my workplace, I deployed my mental illness as a political illustration of the intersections of labour and mental health and as a refusal/inability to mask my neurodivergence.

But (channelling my performance), “I’m ahead of myself again. Can you tell that happens a lot?” (Publius).

In Calgary, Camille Renarhd volunteered to be the Coworker, so I gave her the instructions and sent her off to the sound booth, visible behind a glass pane in the wall. When it became clear that I would not be able to transfer calls to her, I eventually ‘paged’ her (that is, I called for her into the microphone, something I ended up having to do a lot in the performance, becoming something of a running gag).

The stage manager graciously allowed me to use her cellphone throughout the show as the number audiences could call. However, instead of an office phone, the audience was now calling me on an iPhone, and I quickly realized I didn’t know how to, or even if I could, put someone on hold, let alone transfer calls. All of these unanticipated developments led to a surreal pastiche of tech troubleshooting — much as it plays out at work.

The audience was populated primarily by people from my university program, with that relationship largely shaping the audience interventions in the piece. What resulted was an improv atmosphere, where audience embodiments of nightmare customers became increasingly outlandish (such as a man who drowned on the line because the associate who speaks Spanish was unavailable). Most notably, Please Hold became an unintentional intertext with another performance at the conference, with which most of my audience members were also familiar (The Last Tragedy, by Pieter De Buysser, a postmodern work translated and presented by Piet Defraeye, also of the University of Alberta).

Due to the atomization of the audience members suggested by a one-on-one phone call, it was not my intention for their calls to riff off of one another. However, because we were all occupying the same space, the phone became a switchboard mechanism for determining who had the next line. By relying on our collective familiarity with Defraeye’s production, callers ended up talking more so to each other, using me as a bedraggled medium. In keeping with De Buysser’s postdramatic impulse and the collision of texts occasioned by the mystory form, this development effectively derailed my performance — in perfect illustration of my point. It also offered an indirect form of audience emotional labour, rising to meet the level of labour I was performing, so we could all keep the show afloat together.

Ultimately, the final product ended up quite distant from the initial vision, but its hectic improvisation and emotional negotiation demonstrated my intentions better than a polished, well-prepared show could have. The script’s self-reflexivity allowed it to draw insights from other sessions at the conference, while also illustrating the central theme of my regular life (performing and academia) being ‘on hold’ due to the necessity of working. The idiosyncrasies of the conference event gave rise to the accidental discoveries and narratives that emerged in the performance and imbued it with an important extra layer of elastic adaptation that it otherwise would not have had.

The mental and emotional toll of my fragile plans falling apart provided a counter-intuitive catalyst for the political deployment of a gendered, disability-informed performance of emotional labour — thus returning the performance to its original idea and intention.

At both the theatre and the reception desk, the show must go on.

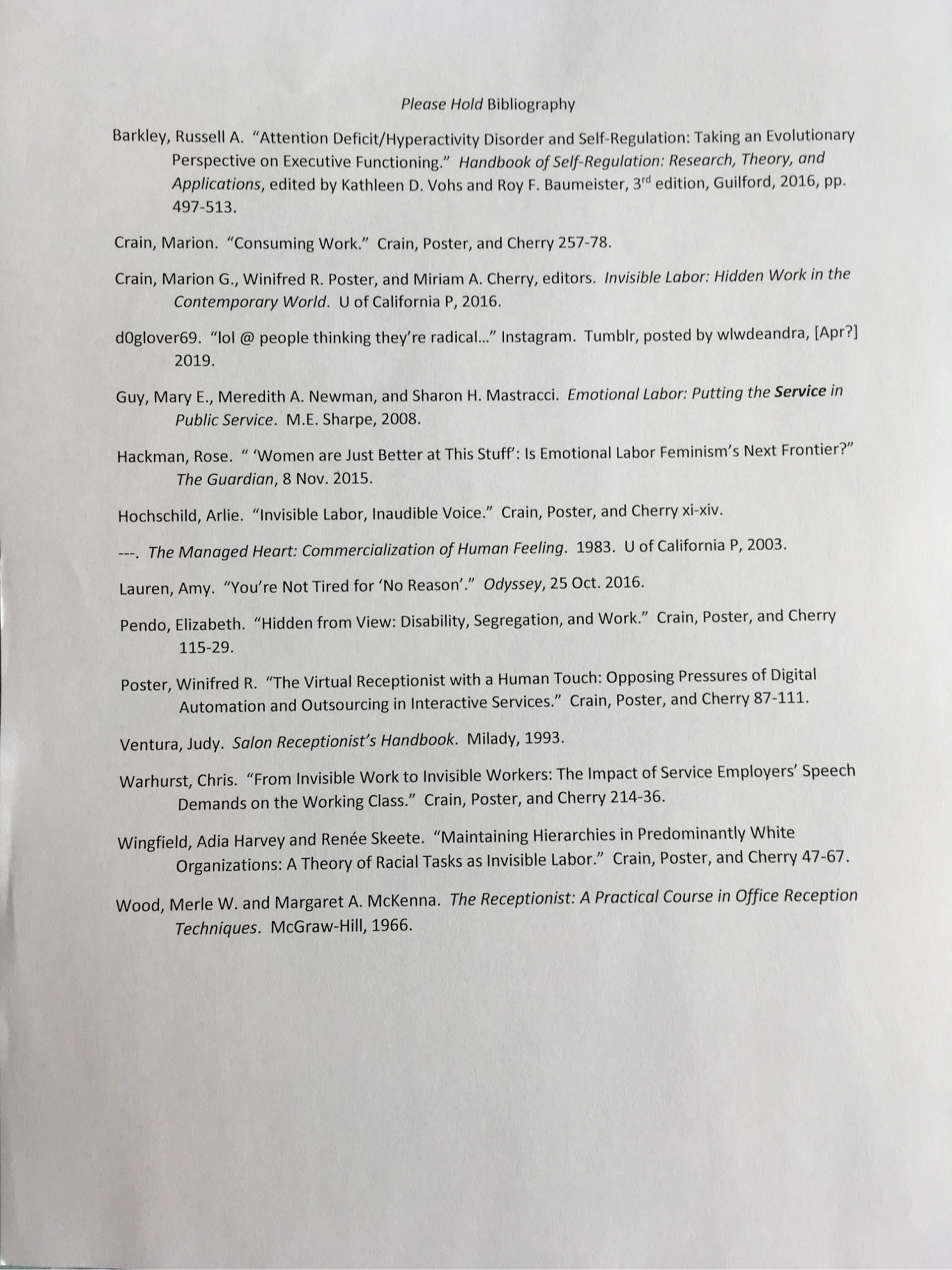

Works Cited

Bowman, Michael S., and Ruth Laurion Bowman. “Performing the Mystory: A Textshop in Autoperformance.” Teaching Performance Studies, edited by Nathan Stucky and Cynthia Wimmer, Southern Illinois University Press, 2002, pp. 161-74.

Hochschild, Arlie. The Managed Heart: Commercialization of Human Feeling. 3rd Edition, University of California Press, 2003 [1983].

Last Tragedy, The. Written by Pieter De Buysser, translated by Defraeye and Mike Devos, directed by Piet Defraeye, performed by Clinton Carew, Gerry Morita, Sara Norquay, Nancy Sandercock, and Lin Snelling, 23 August 2018, Timms Centre for the Arts, University of Alberta, Edmonton [Amiskwacîwâskahikan], Treaty 6 Territory/Métis Region 4, Alberta, Canada.

Publius, Xavia. Please Hold. PSi #25, 7 July 2019, University of Calgary, Treaty 7 Territory/Métis Region 3, Alberta, Canada.