The theme park is only as real as the fantasies it constructs. Often situated away from regular routes of navigation, theme parks are wholly designed and realized spaces that stretch across the fantastic and the mundane. They are built worlds of amazing sights and thrilling rides that sit alongside the pedestrian infrastructure of ticket queues and bathrooms, and are inhabited by those who pay to be there (park “guests”) and those who are paid to be there (park employees, sometimes “cast members”). The facade of the theme park is shiny and seemingly all-encompassing, even as we know there must be a backstage, internal machinery, labour, and garbage. Multimodal and immersive, theme parks present opportunities to consider the networks and spans of relations among performers, spectators, and designed spaces and objects.

In this article, we offer provocations for the field of Performance Studies and re-encounter our work in curating and hosting a theme park named ElastiCity at the 25th annual Performance Studies international (PSi) Conference in Calgary in 2019. In particular, we meditate on the speculative venture of a theme park, with specific regard to its activation of imagined and embodied sociality among both its infrastructural components and the crowds of people who engage with them. Reflecting on theme park visitors’ oscillation between orientation and disorientation once they are past the entrance, this collectively–authored piece mirrors, and to some extent invites, activation of readers’ spatial and temporal orientation and disorientation. We do not presuppose a universal and homogenized theme park audience or reader by doing so. Following Rebecca Williams’ notes (87-8) on theme park visitors’ different levels of immersion and involvement, which complicate the “linear phases” of theme park routes, our move instead recognizes the heterogeneity of readers whose variegated experiences will correspond, even if momentarily, to the elastic capacity of our contribution itself.

Here, the primary points of discussion are interspersed throughout the article as if they were various “sites” within ElastiCity, the theme park created at PSi #25. These sites of discussions are at times conjoined by a collective, unified voice that interlaces both theories and personal narratives. At some points, however, individual voices come to the fore to offer a memory or analysis from a particular point of view. That is, we write as a collective, even as our individual ideas are highlighted in different ways. Indeed, as a way of foregrounding the various individual responses and encounters with theme parks, throughout this article authors’ voices sometimes take a turn from “we” to “I” as a gesture of shifting our focus from our experiences as part of an abstract crowd to an anonymous but distinct individual body that explores, consumes, labours, and quarantines in themed spaces.

Our writing process, sitting as it does between memory and desire, planning and performance, both builds and reflects on the work of ElastiCity. In its juxtaposition of academic prose and performance texts from a “theme park,” we seek to put pressure on the sometimes-flimsy borders that theme parks enact between fantasy of the experience and the ways that workers, “guests,” and others are called upon to perform for the theme park. It is not simply the fictional universe crafted in theme parks that draws visitors; it is also the “earnest” performances of constant border-making and shifting by theme parks’ infrastructure and people’s movement within it.

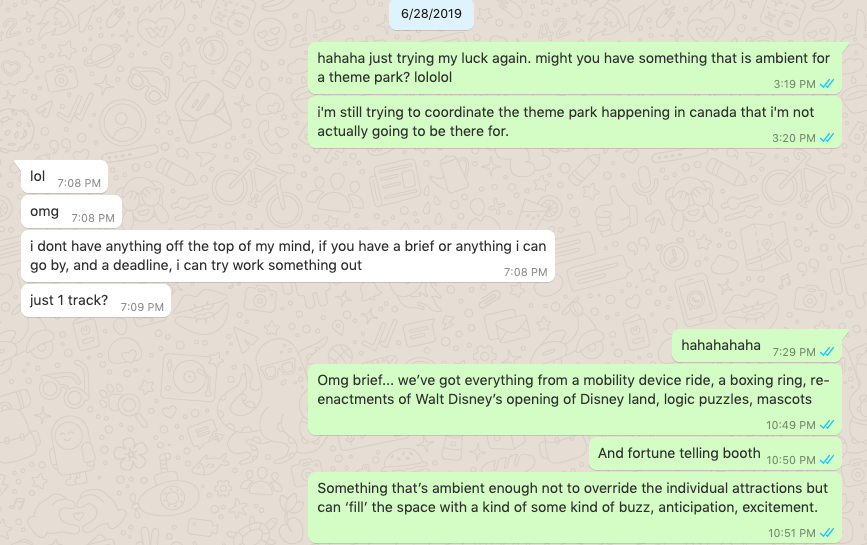

Some of the authors of this article were present for ElastiCity in Calgary, others were not, others still worked on it but then had to leave and thus never saw it open nor experienced it as an inhabited event. Throughout the article, there are ElastiCity interjections that take the form of remembrances, commentary, and speculative voices from the park. We use these entries to remember ElastiCity and our own theme park experiences, sometimes remembering differently, sometimes projecting experiences into an unperformed performance studies theme park. These entries stretch ElastiCity from its performance at PSi in Calgary into this piece of writing, threading it through with imagined responses and projections that play on and with the often-nostalgic affect of theme parks. This expands on the work of our documentation process, creating a narrative beyond the images captured during our time at ElastiCity.

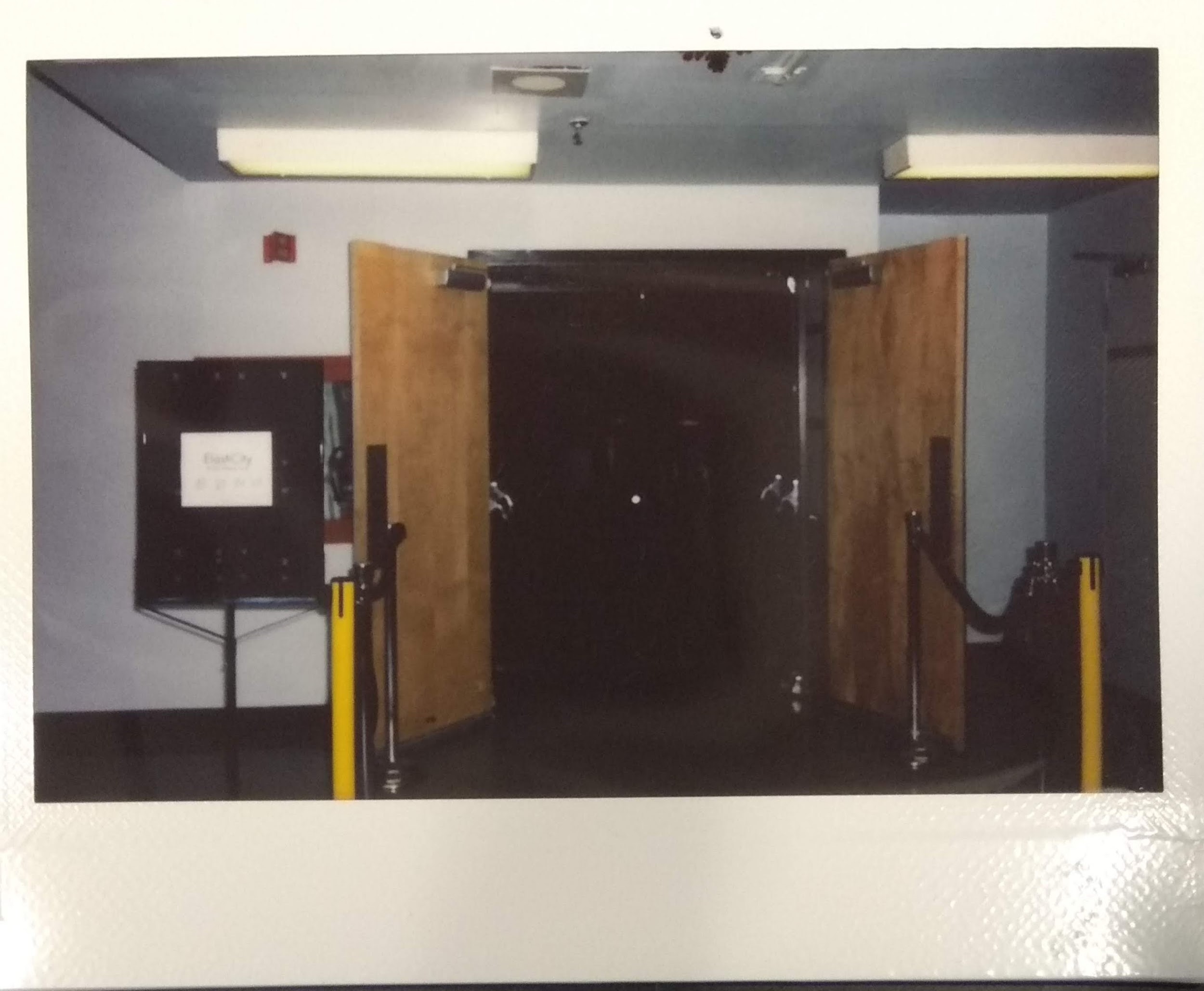

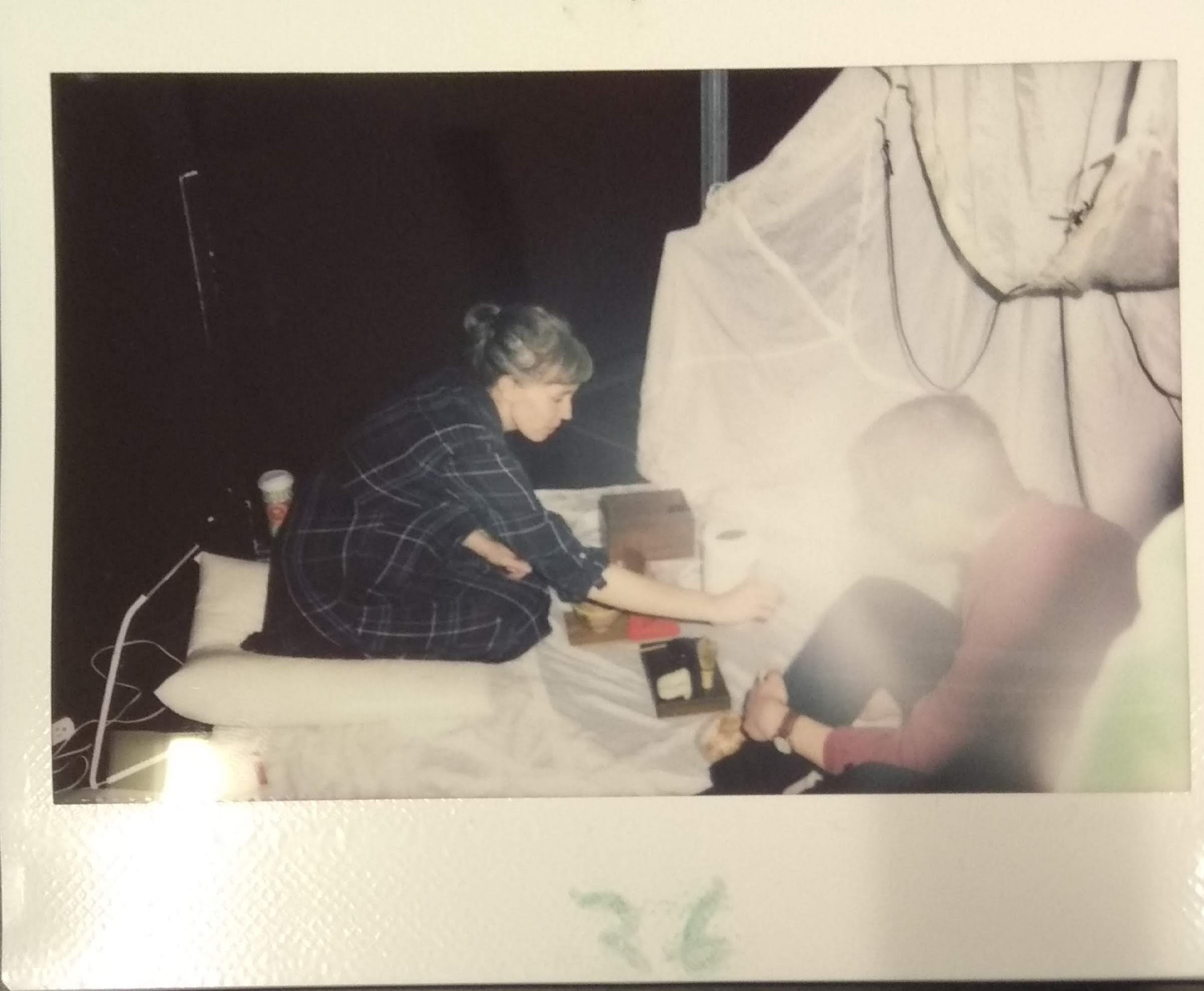

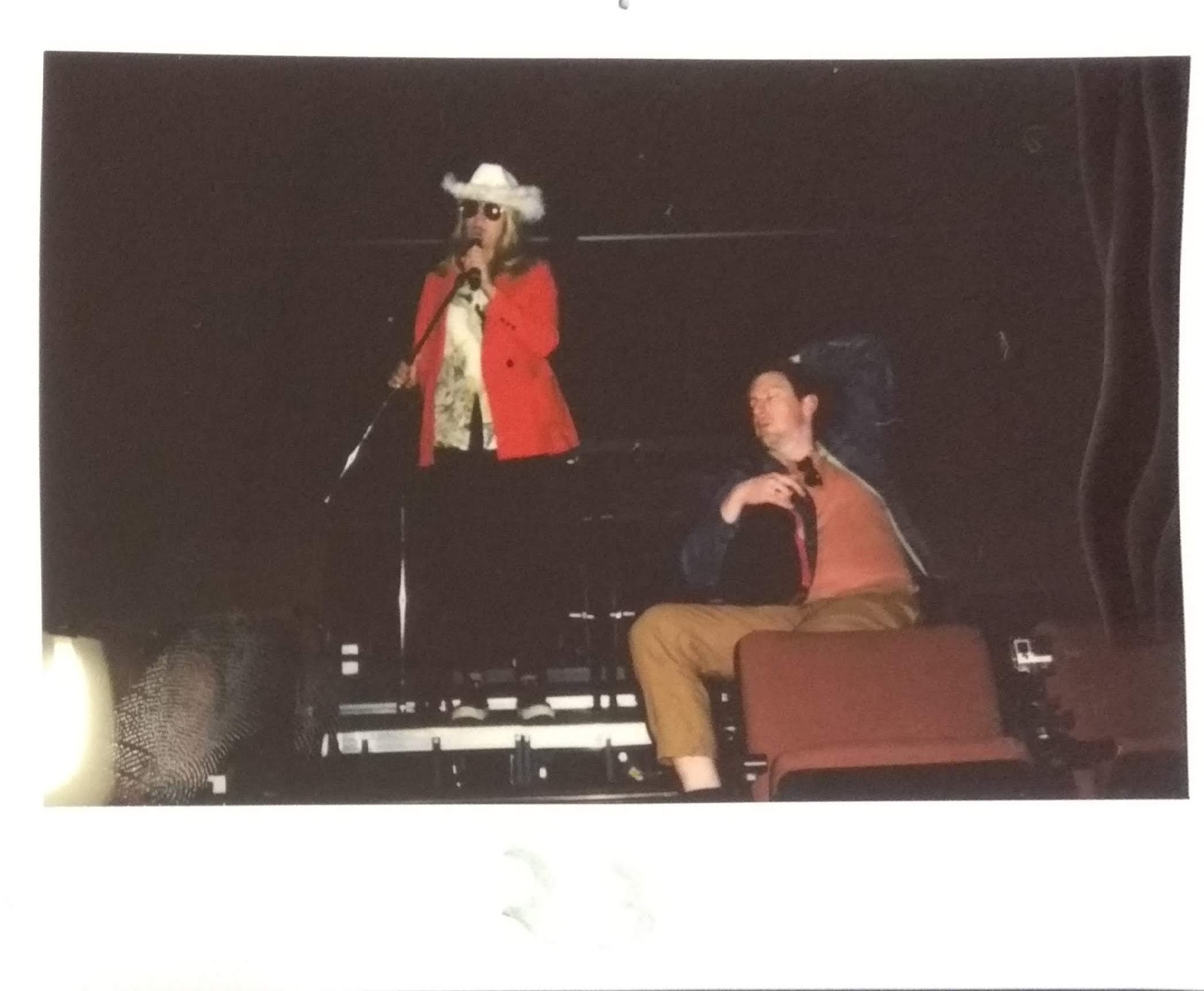

Fragmented memories of ElastiCity are carried by two styles of photographic documentation. The grainy, unretouched Polaroid images, taken and developed onsite, where they were sequentially added to a board outside the park, sit alongside digital photos, many of which have been edited, with Instagram filters applied and borders cropped. Both the analog and digital styles of documentation mimic and perform theme park vacation photos from another era. Conference-goers and ElastiCity participants appear as family and friends, which in the instant of the image, they may well have been. We call attention to these documentary processes as a way of marking the performance practices of theme parks themselves.

ElastiCity was built to materialize a space in which the elasticity of boundaries was not only an object of analysis, as it might be in conference panel presentations, but also a form of embodied performance. Readers of this article can imagine the attendees hopping from a tea ceremony to a boxing ring to a gift shop, all the while being greeted by a bull mascot. Our hope is that readers will immerse themselves more deeply in our theoretical expansion of elasticity, theming, and the spatio-temporal configuration that contextualizes the complexity of pleasures experimented upon in ElastiCity and in theme parks in general. The logic of theme parks pervades this work and, like others who have taken up theme parks (Kokai and Robson 15), we hope readers will navigate their own “routes” through the work by following hyperlinks to the theoretical subsections. Eventually arriving at the closing, readers will have followed the boundary stretching capacity of a theme park that has extended to our everyday lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. In this, we speculate and vicariously immerse ourselves in the theming of life itself, as actual theme park sites are transformed into official facilities that accommodate the “new normal.”

In setting out to engage the intersection of performance studies and theme parks, we curated and built our own theme park: ElastiCity: A PSi Theme Park. The park was staged and had its grand opening (and closing) in July 2019 as part of PSi #25 in Calgary, Canada. In the process of performing a theme park, we struggled through the ontology of theme parks and what ElastiCity calls to question along borders of theme parks and performance installations.

—————ElastiCity—————

I can’t find the edges of the park anymore.

—————ElastiCity—————

As the field of performance studies regularly reminds us, by trying to fake something, you might still end up doing it. The “real” theme park is yet to come; yet to become; yet to be a theme park. As we sprint toward the rides, hurrying past the food kiosks nestled under the castle facades, we all agree: next time we’ll repeat it “for real.”

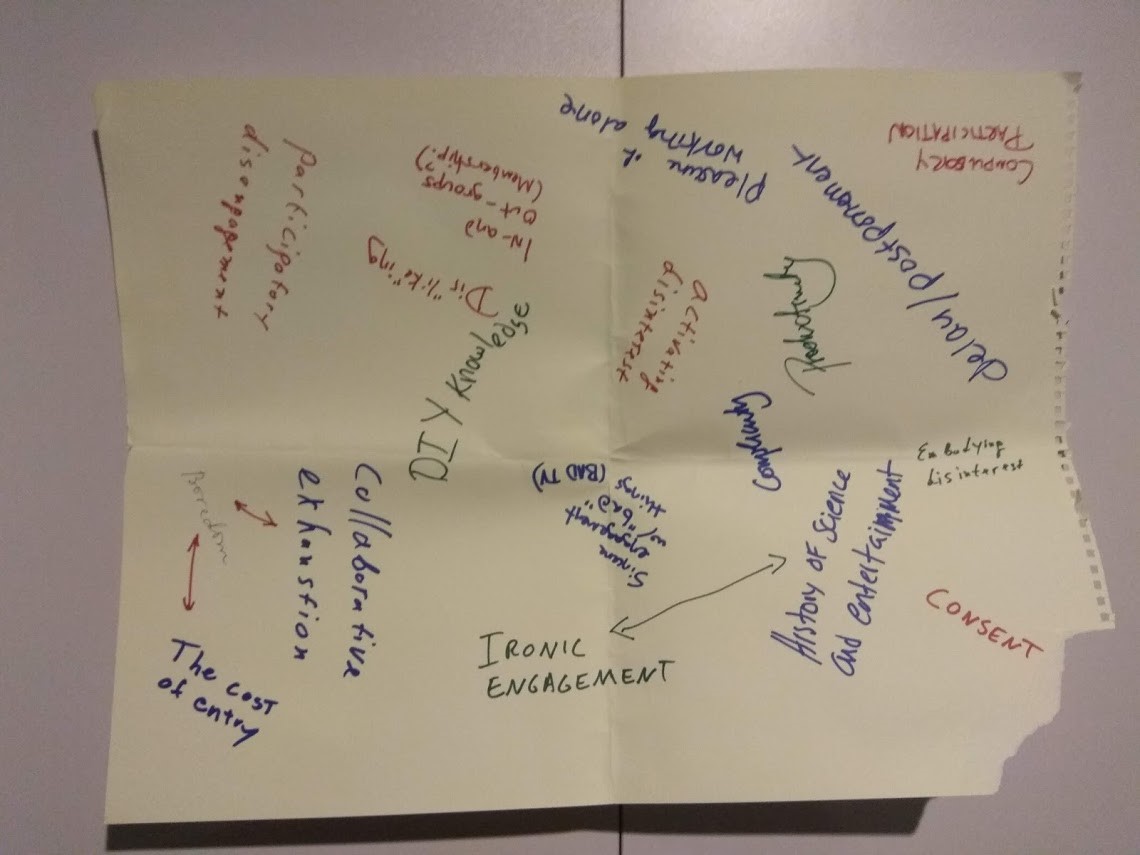

Returning to the beginning: ElastiCity grew out of in-person meetings and discussions as part of the Performance Studies international annual conference in 2018 in Daegu, Korea. Many of us were part of the PSi Summer School, organized by the Future Advisory Board of PSi. In initial discussions of shared research interests, we came together around a variety of concepts related to pleasure, wonder, and performance: boredom and apathy, labour and the maintenance of joy, refusal to perform or engage, fantasy and play (as well as the disillusionment that follows when such spaces are broken) and the intersections of magic and late capitalism. In discussing these ideas (or themes), we found a common object in theme parks and began accumulating ideas for a collaboration to take place in Calgary over Google Docs. Inevitably, the idea was floated: What if we just built our own theme park?

—————ElastiCity—————

Everything feels more real here.

—————ElastiCity—————

With the capitalization of a single letter, the theme of the conference, “Elasticity,” became “ElastiCity,” and we added the subtitle “A PSi Theme Park.” Taking up the conference theme directly in the name of the park pushed us to engage the potential points of flexibility of theme parks, to test the boundaries of what a “theme” and what a “park” might be (together and in isolation), and also how we imagine theme parks into and through performance studies as a practice and discipline. Inspired in part by ironic projects such as Banksy’s Dismaland and dire representations of post-apocalyptic theme parks in pop culture, alongside the more sincere and familiar landmarks in Disneyland, Lotte World, and everything in between, we thought about the “lands” of a performance studies theme park.

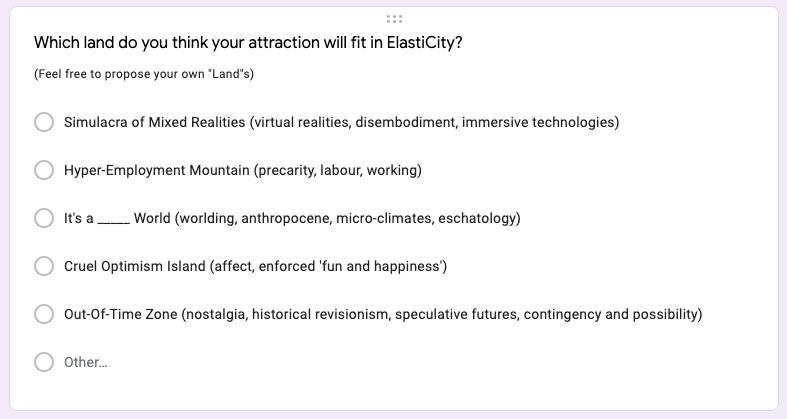

Because theme parks rely on the thematic division of physical space (and the intricate choreography of bodies, genres, and material that results), we began to build the imagined “worlds” of major themes of performance studies: immersion, temporality, labour, affect, and worlding. We imagined that orienting from the Simulacra of Mixed Realities, one could trace the borders of Out-of-Time Zone to reach Cruel Optimism Island. From here, park visitors might glimpse the peak of Hyper-Employment Mountain and scan the horizon of It’s a _____ World. Buoyed by visions of a grand and sprawling performance studies theme park, and knowing the conference would coincide with the annual Calgary Stampede rodeo (https://calgarystampede.com), itself a temporary “theming” of the urban space of the city, we sent out a call for presenters and collaborators for the conference, asking participants to propose rides, games, immersive experiences, and practice-as-research of all kinds.

The call was circulated through various performance studies networks and listservs:

[The event entails] a number of attractions related to the performance research of participants, who will enact and perform their work within the conceit of a pop-up theme park. The theme park will take place over the course of one day of the PSi Conference in Calgary from July 4 to 7, 2019 in a flexible performance space. Audience/attendees will come and go throughout the day. Some theme park attractions may be durational and occur and recur throughout the day, while others may only happen once during the day. Participants are encouraged to think of the various modes of performance of theme parks from rides to interactive games to parades to gardens and museums to roaming characters to gift shops and refreshments. We welcome solo performances, ensembles, installations, and other diverse engagements with performance studies and theme parks.

What does your PSi theme park attraction look like? Please complete the following questionnaire and we will be in touch.

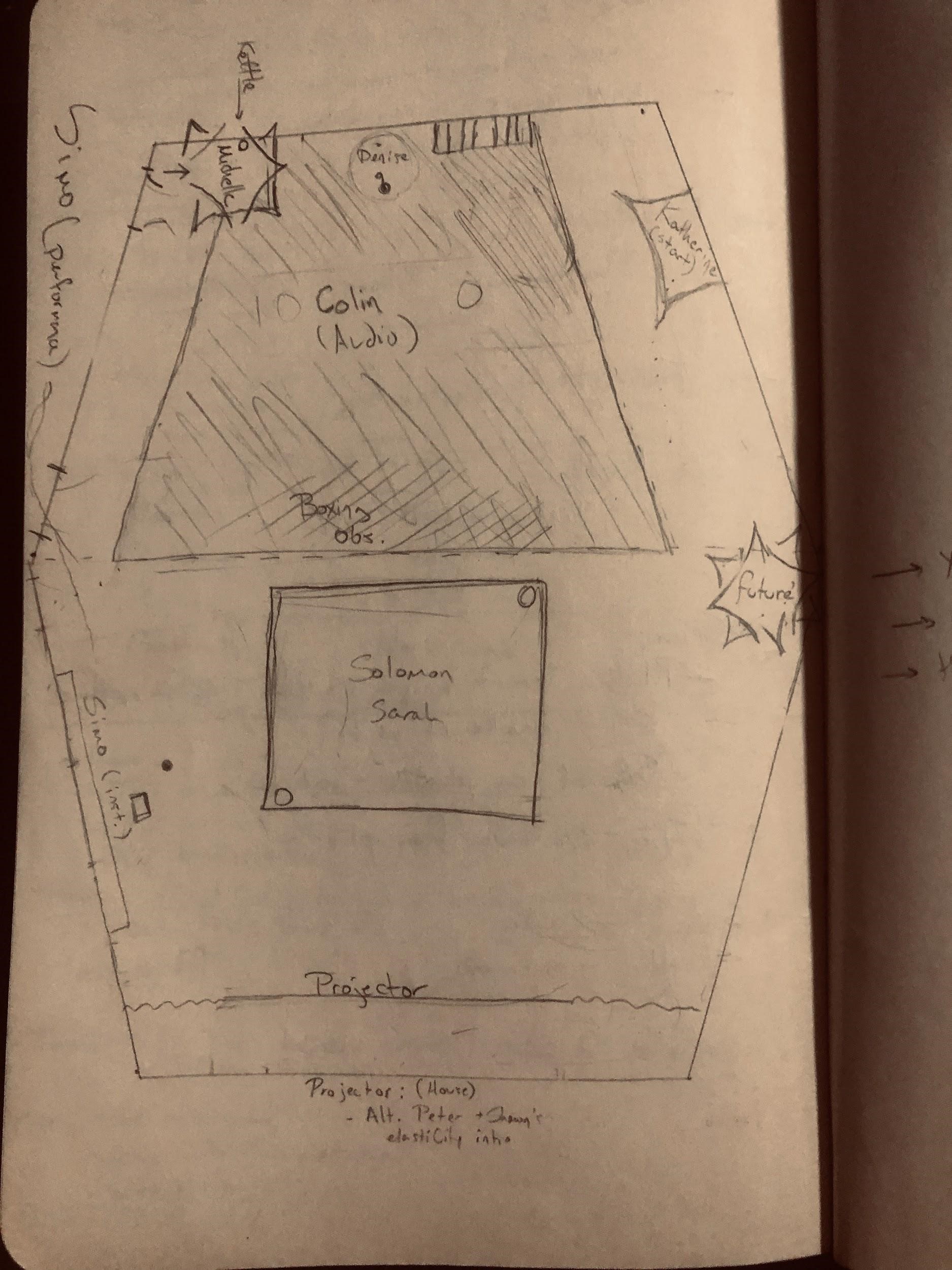

We received enthusiastic participation from a wide variety of collaborators, and the theme park ultimately featured about a dozen works in the Reeve Theatre Primary, one of the theatrical performance spaces in the School of Creative and Performing Arts at the University of Calgary.

—————ElastiCity—————

I was surprised to find so many adults here. Weren’t these things for kids? It’s strange, but I’m not sure I can leave so soon — I don’t know when I’ll be able to come back.

—————ElastiCity—————

While contributors were developing their attractions all over the world, we met regularly to refine our park around the new participants and their proposals. Doing so heightened the differences and expectations between a performance studies theme park and most contemporary corporate theme parks. Whereas most theme parks are centrally planned and designed, our performance studies theme park was necessarily dispersed and horizontally developed. Following this, we found ourselves returning to labour and maintenance as display; favouring intimate personal experiences over the mass appeal of attractions or the constant churn of the character visit (where park guests wait in line for an opportunity for a picture or a handshake with Mickey or Minnie or some other character); asking participants to question their culpability in creating and maintaining wonder; and enveloping the imaginary into the experienced through the mandate to participate. As Denise Ackerl’s theme park attraction proclaimed and repeated to ElastiCity participants and guests: “This is YOUR park.” Even as contributors initially engaged through the conceit of discrete worlds, we began to see ElastiCity as a world in itself, one which also highlighted the performativity of theme parks and the key themes that drew the project into performance studies: spectacle (a constant source of delight and frustration for the PS scholar), immersion, temporality and duration, and staging and framing.

These principles guided us in building the park and realizing an elastic vision. Working closely with the carpenters, scenic artists, and technicians of the School of Creative and Performing Arts, we divided the space, constructed areas for each ride or experience, and developed pathways that let parkgoers wander freely (while still subtly suggesting where they might turn their attention, or what seams they might conveniently miss). It turns out that building a theme park looks a lot like staging theatre and performance, and the theatre technicians among us found that many of our skills translated neatly. The park came together with some ingenuity, a shoestring budget, and a firm belief in the power of magic. ElastiCity sprung to life, if only for a moment.

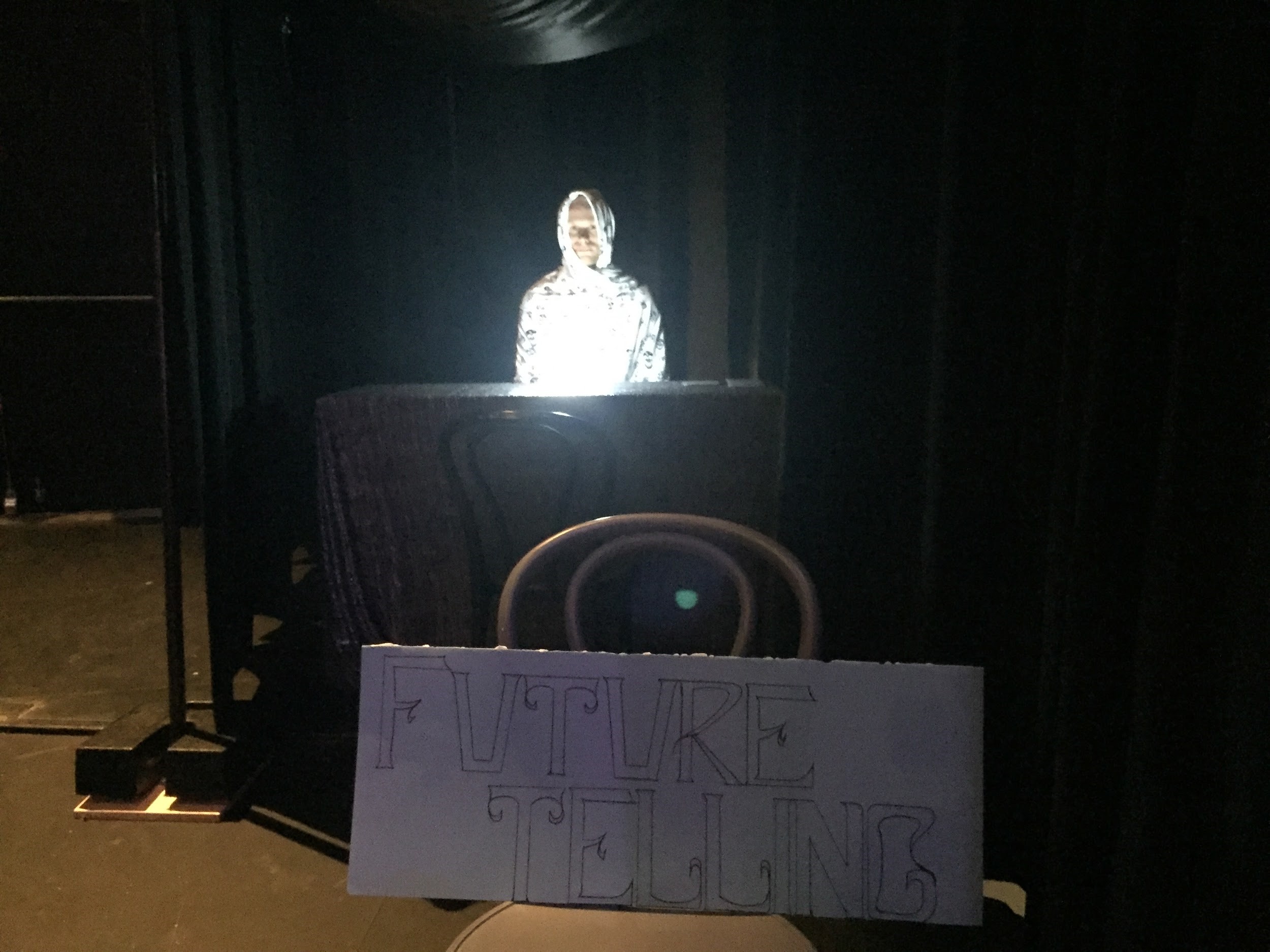

You enter ElastiCity on a recommendation from a colleague, or maybe you find yourself lost in the haze of an academic conference and stumble into the room by mistake. Perhaps you encounter one of Petra Kuppers’ “disability rides” out in the world, or you are drawn in by our bull mascot. In any case, you enter the park and its sights and sounds. Soundscapes collide and complement one another as our announcer melodiously welcomes you to “YOUR park,” and you hear the ghosts of prior guests repeated oh-so-subtly through Colin Tucker’s live sound installations as you disperse among rides, games, and experiences. Perhaps you participate in a tea ceremony with Michelle Liu Carriger in a diaphanous tent, or get a fortune reading from the PSi Futurists in the Future Telling booth, engage Simo Kellokumpu’s movement and media installation, play Kathryn Blair’s game to learn to be an algorithm, get your photo taken old-school-style by the roaming photographer, or perform some unusual labour for an as-yet-unknown future artistic purpose. And, of course, you can’t miss ElastiCity’s “weenie”[1]: a boxing ring open to all comers, hosted by scholars and boxers Sarah Crews and Solomon Lennox. On your journey into wonder, you make a mental note to get a photo souvenir of your day and, of course, exit through the cashless Gift Shop™, where gifts are purchased with gifts.

In developing a PSi theme park, we came to better understand the stickiness of the concept of the theme park. Had we merely curated the various performances to fit in a room or a gallery, we might have lost the many affordances of the theme park, including the expectations of those who walked through and engaged. We found the theme park framing allowed us to wrestle with immersion in novel and exciting ways. By deliberately situating our theme park within the Performance Studies international conference, we sought to activate the concept of elasticity as an alternative world, one which stretches the boundaries of the real while relying on strict definitions of inside and outside to reinforce itself through performance.

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

Do theme parks dream? Do theme parks want to be entertained? Theme parks, and the simulacra of reality and fantasy that they conjure, function in variously troubled relations to the spaces outside the walls of the park. A number of recent studies point to the increasing interest in theme parks (Kokai and Robson; Mittermeier; Williams) and draw on various disciplines ranging from media and fandom studies to labour and celebrity studies. For instance, Jennifer Kokai and Tom Robson’s edited volume, Performance and the Disney Theme Park Experience: The Tourist as Actor, engages closely with theatre studies through tourism studies and by centering the analysis around those who attend theme parks as actors and spectators. Or, as Andy Lavender reminds us, “Visits to theme parks provide an array of performance situations and arrangements that put the visitor amid tropes of theatricality” (200). Indeed, we are called to perform for the theme park, to enliven its theatricality. As Baudrillard explains, writing about Disneyland:

[...] it is a play of illusions and phantasms: Pirates, the Frontier, Future World, etc. This imaginary world is supposed to be what makes the operation successful. But what draws the crowds is undoubtedly much more the social microcosm, the miniaturized and religious revelling in real America, in its delights and drawbacks. You park outside, queue up inside, and are totally abandoned at the exit. In this imaginary world the only phantasmagoria is in the inherent warmth and affection of the crowd, and in that sufficiently excessive number of gadgets used there to specifically maintain the multitudinous affect. (Baudrillard, Simulations 23-24)

The theme park thus not only places us in the center of theatrical tropes; it also calls us to perform in highly theatrical ways. It needs our “warmth and affection,” our active performances.

—————ElastiCity—————

I couldn’t have imagined. I’ve always wanted to be here.

—————ElastiCity—————

Theme parks need an outside in order to differentiate themselves. Baudrillard’s insight here is that theme parks do not hide the ugly truth from the “real” outside world; rather, they repackage and sell segments of the “real” as magic. Jane Desmond (1999) further notes that theme parks often promise to deliver a more “real” version of the world. As with many other forms of performance, the question of bodily presence (or the lack thereof) is central to the ways theme parks are performed over time. A theme park, like a theatre or a performance studio, needs people to enliven it physically and psychically. In writing about Universal Studios in Florida, Stephen Di Bennedetto observes, “At the themed attractions we are free to act out our fantasies of being a part of the actions of the fictional worlds we know from the movies or from literature. We navigate the crafted environment” (58). Without those who project themselves into the “crafted environment,” theme parks disintegrate, their constructedness is glaring and abrasive.

Existing as a themed world outside the day-to-day performances of guests and employees alike, theme parks enact alternate visions and ideas of what a world might be. We see renewed academic interest in theme parks in part as related to the (re)emergence of immersive art and performance (see Bishop; Harvie; Schechner, among others). But what sets the theme park apart from some of these more academically respected incarnations of theatrical and artistic immersion? Even amidst this shift of attention toward immersive art, theatre, and other environments, other forms of immersion from the past are receding (suburban malls in the US, for example). And why does the theme park feel so familiar in such disparate parts of the world? Within this speculative framework, and as we scan our tickets and navigate the turnstiles one-by-one, we ask not only what would a performance studies theme park look like, but what does a performance studies theme park do?

—————ElastiCity—————

i spent my youth frequenting the four local amusement parks in L.A. that my family had annual passes to. on the off-seasons, my friends and I learned to lean into construction. we learned the rules and performed the behaviours. we ate where everyone else ate. we walked among them shoulder to shoulder.

as i grew, older and taller, i grew tired of the tireless efforts machining my gaze…the seasonal special (those moist turkey legs tho), the smoke behind the fence, the disillusioned workers whose eyes lit up only on stage, and flecks of peeling paint in the neglected corners of the park where no-one dares to look.

i left with only traces and outlines. i’m a hopeful ghost at best.

—————ElastiCity—————

Theme parks perform the elastic boundaries between fantasy and disappointment, wonder and boredom, pleasures and apathy. How might we view theme parks’ elasticity — that is, their capacity to simultaneously stretch and compress themselves as an activation of new forms of affective economies, social relations, and labour practices?

Seriousness collides with the material reality of theme parks, stretching to make sense of its edges and borders. Theme parks are corporate and inartistic, regressive and blasé. In their management and profit-making efforts, however, theme parks make their earnestness visible: different theme park businesses compete against one another; theme parks boast about their “committed“ staff; development of theme parks begins with solemn plans. As in other themed environments, the constant invitation to immerse oneself in the deluge of spectacles overwhelms (see Carriger and Laine).

—————ElastiCity—————

Suspend your judgement. There is nothing fake.

Your reality is here. Love every moment.

—————ElastiCity—————

With ElastiCity we regularly grappled with our instinct to ironize the theme park. We aimed to reroute the theme park’s seriousness away from mass consumption through one-on-one experiences: works such as Carriger’s tea offerings, the Futurists’ card readings, and Crews’ and Lennox’s boxing match were all designed for only one to two participants at a time. ElastiCity also continually played on the use of borders in theme parks, the complications of which are mirrored in theatrical practice. Nevertheless, there are glimmers of moments when the edges of the world, the borders between the real and the fantasy envisioned and managed by theme parks, become evident. The earnestness of theme parks suddenly emerges from beneath the carefully themed overlay.

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

The notion of “theming” has been taken up by corporations, governments, and researchers over the past several decades and is well documented. According to Scott A. Lukas, some of the modes for theming include architecture, material culture and design, narrative, technology, performance, and guest role/drive (A Reader 5). Themed spaces occur in a wide variety of locations, ranging from purposeful sites of performance to corporate and retail environments. Lukas’ list includes: theme park, world exposition, themed restaurant/bar, lifestyle store, brand space, cruise ship, casino, museum/interpretive center, home, immersive performance space, virtual space, affective and subcultural themed community (5). It seems that almost any space is potentially themed. These spaces call us to perform, to encourage us to buy, be bought, and perform for companies and products (Wickstrom, Performing Consumers).

Times Square in New York City was notoriously re-themed in the late 1990s as Disney and other corporations were offered discounted real estate and tax incentives to “develop” the area (see, for example, Hillary Miller and Samuel R. Delany). Such moves have similarly taken over other entire cities like New Orleans (Souther). ElastiCity and the Performance Studies international conference occurred amidst the annual Calgary Stampede, wherein the city of Calgary is overtaken by a country and western “theme,” which Kimberly Skye Richards argues overwrites a colonial history of extraction. While not explicitly a part of ElastiCity (which had initially been conceived of before we knew where the 2019 conference would be located), the Stampede influenced our choices from the circulation of cowboy hats to the birth of our celebrity bull mascot. Theming facilitates larger political and economic projects and need not be restricted by size; some have noted the theming of entire countries from the US to Singapore (Chang; Gottdiener). We are also struck by the ways that “theming” proliferates in the education sector. Universities have long marketed themselves as “educational theme parks” attracting potential “customers” (students) (Symes 145).

—————ElastiCity—————

I don’t remember, but my mother tells me I was five when we went to Disney World. In the mid ‘90s it was popular to schedule ten-day stays in one of the park’s on-site resorts, for a 24-hour experience of constant immersion. I’m told I loved it. I don’t remember.

Apparently I started to catch on around day three, and proceeded to badger my mother, asking about every character, every ride, every set piece, “is this real?” Ever honest, she told me, no, and no, and no. Apparently nothing was real. I don’t remember many details after that. Immersion for ten days does things to you, I suppose.

Apparently, I broke toward the end of the trip, somewhere around the Magic Kingdom, sitting in the idyllic courtyard watching the ducks in the pond. This time I didn’t ask, I already knew, and I confidently pointed at the ducks and proclaimed “those aren’t real.” My mother looked on in horror. Did she answer? I don’t remember.

—————ElastiCity—————

In theming universities, performance is often mobilized as a broker between the global market, research institutions, and their outposts (see Lim). Stripped of its political force, performance becomes a tool for students to enhance “entrepreneurial spirits” with a “creative edge” and a “progressive mindset.” Often, the theming of a location and the theming of a university work in tandem to create a theme park-like infrastructural project, where state-of-the-art performance venues and museums take center stage for the intended spectacularity (Lim 36-38). Theming at various scales, as such, reshapes the branding efforts of universities and their pedagogical practices, institutionalizing management techniques required for the race to “excellence in education.” Randy Martin describes of New York University, for example, “As with the branding campaigns of New York City itself (‘I ♥ NY’), which saw its real estate fortunes soar, the university underwent a dramatic makeover under the fiduciary eye of the city’s re-energized realty moguls” (119).

In those fantasies, we all become what Baudrillard calls “interactive extras [figurants interactifs]” (Baudrillard, Screened Out 153). In the context where theme parks are perceived as exceptional zones, the question becomes something about the origin and location of the exception. The “politics of inclusion/exclusion,” as described by Scott A. Lukas (“Time and Temporality”), are in full swing here, with a bit of twist. It is not that you can be locked-out and excluded as a guest but rather that you are locked-in as a participant into the system of magic and wonder. The intrinsic logic of the theme park does not operate in the binary opposition between “inclusion” and “exclusion” only, but in a more convoluted way — everyone is always welcome in the theme park, so long as the stay isn’t permanent, and the theme park must always exclude external reality in order to preserve its amusement vortex. In other words, a guest in a theme park is in a state that “doesn’t exclude him nor really include him; it excludes him through its inclusion and includes him through its exclusion” (Tiqqun 76).

In this understanding of inclusion/exclusion, ElastiCity has a strange and etiolated relationship to “fun.” Several of our “acts” take the form of games, the tone of which range from confrontational — such as Kathryn Blair’s carnival game, which invites the player to step into the role of artificial intelligence-in-training to demonstrate the pervasiveness of AI bias — to exhausting, as no participant thus far has successfully managed to last three rounds of boxing with Sarah Crews or Solomon Lennox. Roger Caillois famously classified games into four categories: agon (competition), alea (chance), mimicry (simulation), and ilinx (vertigo). Ilinx is the Greek term for whirlpool, from which the Greek word for vertigo (illingos) is derived. Beyond the immersion promised by simulation, theme parks play on the disorientation of vertigo that centrifugally pushes the viewer out and around the park, eventually toward the exit. In ElastiCity, fun is alienating, contemplative, awkward — the looping sound and video playing throughout the space seems to demand this — and for those on the receiving end of the punches in the boxing ring, it is all potentially a bit painful.

The magical fantasy of the theme park is sustained by its capacity to offer a continuous stream of new experiences, and the mystery that accompanies the new. Caillois describes ilinx as “a pure state of transport” (31); theme parks are not only transporting they are resolutely liminal. There is no destination here, only the sense of continual arrival that reveals itself to be the path towards the next attraction. You arrive at the attraction, to queue for an incommensurably long period, only to be on a ride that lasts for a few minutes. Then, you’re expelled to wander towards your next attraction. ElastiCity mimics the theme park’s ilinx by offering continually new experiences. Petra Kuppers’ “disability rides” invite the participant to navigate the University of Calgary campus differently, while reminding us how localized all experiences can be. Similarly, Colin Tucker’s reactive soundscape records and iterates on the noises made by ElastiCity’s guests, the room slowly filling with the sense of excitement, irrespective of the conditions in the park itself. Lost in a sensation of perpetual transport, the theme park choreographs this perpetual movement and restlessness.

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

What does the theme park want? Shawn asked me this shortly after we entered Everland in Seoul, Korea. I think I answered something about money, but once the financial transaction at the front gate has passed, the theme park seems to want more. Even the gift shop, as a store within a larger corporate space, is selling more than plush toys and princess costumes. The store offers up the possibility of preserving a feeling, a memory of the time in the park. The souvenir that brings you back to a particular time and day. The theatricality of experience and commodity, together in performance and purchase (see Wickstrom, “Commodities”). The theme park wants to be remembered—it wants to inhabit you after you leave. Who works for whom? The theme park is so pervasive and encompassing that it accommodates nearly every affective response, even as it demands more.

—————ElastiCity—————

Okay. I think I found an edge. Tomorrow I will take the leap. I don’t know what’s happening here, but I think I will like it.

—————ElastiCity—————

Perhaps the theme park’s desire is bound up in the desires of its builders. Historical lore contends that Walt Disney broke the ground on Disneyland, as though his vision sprung from the earth by sheer force of American exceptionalism and drive. But thousands of hands take on the active work of crafting wonder, and the maintenance of astonishment is a labour all its own. As a performative theme park, ElastiCity is sustained by the collective work of believing that it is a theme park as much as the craft and physical labour of constructing the space. The theme park’s demand for affective labour is a unique one, not only demanding that all participants, worker and parkgoer alike, joyfully engage, but that such wonder must be constant and durational in order to be legitimate. Artist-labourer Bojana Kunst demands that we “think in the direction of duration as a dispossession that overwhelms us with non-functioning and non-operativity” (130), a dispossession where the theme park might locate its entire being. Indeed, the space must function and operate perfectly in order to enable a durational non-functioning and non-operativity for its customers; they must simply take in magic. But magic is, and has always been, work. The labour of the theme park is both obvious and obscured. The theme park workers range from seasonal and visiting employees to students (sometimes working for credit or as interns) to the working poor (who often sleep in their cars) (Medina; Velasco).

ElastiCity is already leaving our group with many leftover objects, found and bought for use in the park and now just an odd assemblage of junk. So we take them with us as souvenirs. The theme park souvenir is a unique bridge between realities, a direct conduit to the not-space and not-time of the theme park. This is one of the most direct connections between theme parks and theatrical practice. Several lives ago I was a props carpenter, a position where the majority of one’s time is spent shopping for ordinary objects and tweaking them to fit into another reality. The souvenir also intersects with a critical tourism studies vehicle, the gift shop. In ElastiCity, our Gift ShopTM was an afterthought driven by an excess of props, a place of gifts without commerce, branding, or direction. It suggests the gift in its wretched form of exchange: Barbara Browning notes the word gift in German means “poison,” and that the ecstasy of the gift is that it is always insufficient (see Browning 2017). A Carnival of Value, indeed.

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

The time of the theme park is, in theory, infinite. In ElastiCity’s “Out-of-Time Zone” we contend with the ever-present nowness of the theme park in a space that is, in fact, very tightly bound by duration, international time zones, and logistical limitations. It operates in what Jack Self and his collaborators call The Big Flat Now. While the authors direct The Big Flat Now more as a critique of internet culture, the concepts of Nowness and Flatness they articulate were earlier perfected in the space of the theme park. The theme park’s Big Flat Now must account for two forms of duration; it seeks to both maximize the amount of new experiences to offer its visitors (Nowness), and to promise that it will be forever the same (Flatness). So why do theme parks feel so connected to temporality, and particularly the future?

—————ElastiCity—————

The hardest part of falling for two and a half years was the landing.

Breathless, I gazed up at the bright lights of a theatre, surrounded by people dressed up as intellectuals and creators. They lived in a flurry of the imaginary, concocting new realities at every turn. The seams were fully visible, yet their performance was incredibly believable.

When they weren’t looking, I took a name tag and tried to blend in.

—————ElastiCity—————

It seems an oversimplification that the reason is Disney, but Disney might be unavoidable. In “Assuming Responsibility for Time,” L. M. Sacasas notes that Epcot (formerly EPCOT Center) at Walt Disney World drew its inspiration from World’s Fairs and was not really a theme park at all. Standing for Experimental Prototype City of Tomorrow, Walt Disney “had intended Epcot to be a working city, which would never cease to be a model for the future” (Sacasas 2020). When Disney World rebranded in the 1990s, Epcot underwent a major overhaul and integrated its futurity into a more traditional theme park experience. In doing so, it became something of a time capsule. Always a little dingy and retro, as its representation of the future becomes perpetually outdated, it offers a constant reminder that maintaining a model of the future is expensive and logistically exhausting as that future is overtaken by the present, and its visionary appeal becomes “retro.”

—————ElastiCity—————

It was the cloying smell of churros, buttered corn, and soft serve. I remember it vividly when our family all went to the first major theme park in the country. We refused to ride anything. Our inaction did not yield any return values for the expensive tickets. Our father sat down on a bench gazing at the dizzying scene of attractions, as if to prove his presence.

We sat around and did nothing but ate a ton of American junk food. Theme parks were my greasy delights.

Enjoy the smell of popcorn before they all crumble into rotten pieces. Happiness is just one bite away.

—————ElastiCity—————

Every theme park, in some way, evokes another theme park. Groups stay together or they split, half going to get greasy eats, others going to take photos with costumed characters on the opposite side of the park. There are long and winding paths, so guests exchange stories of embodied memories, asynchronous experiences, and affectual objects. Inevitably, in my recollection, it comes up that I wasn’t present the first time I went to a theme park. There is photographic evidence of my presence, anecdotal accounts of how much I enjoyed myself, even merchandise that materializes this episode. All these accounts conspire to persuade me that I’ve been to Disneyland, but I was too young to consciously recall that experience. What I do remember now, as an adult, however, is being enthralled by the videos of the Disney Sing-Along Songs that brought you on a virtual tour around the theme park. Perhaps I was trying to rehabilitate that memory through this virtual re-enactment. I was also told that I was so captivated by the Ferris wheel that I fell backwards while tracing the ascent of the capsules. I was always either too near, or too far, suspended between the poles of elastic proximity.

But even when I did physically enter a theme park again many years later, I carried the same dissonance of proximity. Somehow, finally being “inside” the theme park, I felt paradoxically too close to be fully immersed in its world. The fantasy of the world could not accommodate my boredom, and I found myself working hard to sustain the affective performance that seemed to be a requirement to be a denizen of this world. I found myself relieved when I stepped out of the theme park, thankful that I hadn’t been exposed as an imposter with my affective misperformance. It was much easier to weave fantastic narratives about my experience upon my departure. Or to fantasize about an experience I was never there for.

Combined, then, these fragments frame my orientation to theme parks: vertiginous displacement. It didn’t seem surprising then when fate conspired once more in 2019 to keep me from attending ElastiCity at PSi. After months of planning, collaborating, and devising ElastiCity, the theme park eluded me. Still, the conversation continued on, and I continued to coordinate remotely, participating virtually through messaging platforms, human proxies, and digital avatars. Arguably, as organisers, developers, and designers of the theme park, we could never really attend it with the same presence of our immersants.

—————ElastiCity—————

I’m sweating. A lot. The thick foam headpiece is squeezing my temples. I can see, blurrily, through small mesh holes that are not actually the eyes of the mask. I am vaguely aware of a piece of exposed skin, or maybe just a tear on the fabric of the suit, somewhere near my right ankle. It’s cool, which is refreshing, but troubling since it means the costume is compromised. Any suspended disbelief of this costume and this character being anything other than a sweaty person, stumbling around in public, is now harder to maintain.

—————ElastiCity—————

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

The “speculative” element of the theme park constantly traverses this project. The word “speculative” has recently come to highlight the quality of the undefined and undetermined, in recognizing the imaginative possibilities and futurity that emerge from the present state of being locked into a specific temporal condition. Speculative thinking of the what-ifs, according to Aimee Bahng, could “take the shape of radical unfurling” rather than “protectionist anticipation” based on “predictive calculations that perpetually attempt to pull the future into the present” (7). Speculation as a critical inquiry provides us with an opportunity to look forward to what has not yet arrived but is still possible. And within this essay, there are multiple layers of speculation: Not only the speculative theme park itself, but the fact that some of us writing were unable to attend the event in Calgary, and can therefore only imagine its presence.

—————ElastiCity—————

Yet, my speculation is only merely based on the present moment, a what-would-have-been rather than a subjunctive if.

There is no immediate future to imagine, so I watch videos of other people doing things for me, on behalf of myself, to imagine what I could have done instead.

—————ElastiCity—————

As the two halves of our group come back together to continue our work on this essay, and as we return to speculate on/through last year’s experiment, we further find ourselves in what is perhaps the most highly elastic immersive experience of the 21st century. The global coronavirus pandemic now sweeps across all aspects of daily life, simultaneously erasing and heightening the borders of inclusion and exclusion in geopolitics, economics, and social practice. It confines us to our homes from New York to New Zealand, making coming together in collaboration virtually impossible to do in person — for instance, at the 2020 PSi conference (postponed to 2021), where we might have met to revisit this work. It challenges immersion in ways predictable and entirely unforeseen, bringing both theatre and everyday life online to be “live” but not live, offering new ways to connect while stretching the absolute limits of suspension of disbelief.

—————ElastiCity—————

I have been working from home and living vicariously through others’ lives, or at least seeing the surface of them. Procrastinating, I obsessively watch videos of others across the world visiting empty theme parks, which look like urban ruins you might have seen in 28 Days Later. There is no disclaimer clarifying whether the video was taken before the crisis. In fact, the whole point of the visits is precisely to show what theme parks could have looked like if they weren’t so crowded. Some say this is a gesture of mourning the loss of living the present. I say this is already my present, but a speculative one.

—————ElastiCity—————

In 2020, COVID-19 has evacuated theme parks all over the world. In Singapore, the accommodation D’Resort, appended to the water theme park Wild, Wild Wet, was converted into community isolation facilities, housing patients who are well but who are still testing positive for the coronavirus. During the period of the lockdown, the Facebook entries of the resort were interspersed with daily logs of people posting from their isolation. In an elastic twist, the extraordinary space of the theme park was stretched into a dwelling of crisis, suspended as a Moebius strip of escapism and containment. As uniquely strong exclusion zones, resorts have a novel use as tools for quarantine.

As hyperreal symbols of hope and joy, as well as bellwethers of tourism, theme parks are important indicators of the “return to normal” and may provide glimpses of the world to come. And while we’re all stuck at home, writing from behind our computers, vicarious living opens the world up to a new kind of enjoyment, potentially creating a version of our ElastiCity experiment and performance in the experiences we once took for granted and found mundane. If there can be a theme park at PSi, can there be a theme park anywhere? When we began this experiment, we never thought its boundaries would stretch so far.

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

We’re back at the gift shop. We know there isn’t much we can physically take away from a performance. In a museum, in a theme park, you have the gift shop. In returning here as a way of closing, we ask again what a performance studies theme park does. In creating and curating ElastiCity, we took up theme parks not only as a curatorial theme but also a structuring logic and a methodological frame. The theme park is intentionally full and overwhelming. It is not an empty space, but rather overwrites its space. ElastiCity asks us to consider the elastic boundaries of art, theme parks, and academic conferences. The differences between performance installation and theme park blur and erode as a product of the work we performed, seemingly determined in large part by name. Was ElastiCity an attempted theme park, a pilot theme park, a pop-up theme park, a makeshift theme park, a liminal theme park, a version of a theme park, a speculative theme park, an illusory theme park? Was it actually unrealized, a prototype for a future performance studies theme park? Or, perhaps, we began with the notion that it would obviously and necessarily be incomplete, yet in the end, it nevertheless manifested as a theme park. As we recede into the backstage in the memories of this theme park, we continue to hold the precarious worlds promised by theme parks even as those promises stretch the world we already know.

—————ElastiCity—————

Upon exiting The Final Gift Shop™, turn left at the empty sporting arena, wander past the abandoned theatre, follow the trail of discarded gloves, and join us again in ElastiCity.

—————ElastiCity—————

Return to the ElastiCity MAP

A term coined by Walt Disney (Schweizer and Pearce 100; Coons) for a landmark that draws visitors to specific areas in a themed space. ↑

Bahng, Aimee. Migrant Futures: Decolonizing Speculation in Financial Times. Duke University Press, 2018.

Baudrillard, Jean. Screened Out. Translated by Chris Turner. Verso, 2002.

———.. Simulations. Translated by Paul Foss, Paul Patton and Philip Beitchman, Semiotext[e], 1983.

Biggin, Rose. Immersive Theatre and Audience Experience: Space, Game and Story in the Work of Punchdrunk. Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

Bishop, Clare. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. Verso, 2012.

Browning, Barbara. The Gift. Coffee House Press, 2017.

Caillois, Roger. Man, Play, and Games. Simon and Schuster, 1961.

Carriger, Michelle Liu, and Eero Laine. “Annotating Vegas: Mapping Performance Interventions at ATHE 2017.” Theatre Topics, vol. 28, no. 1, 2018, pp. E-1-E-3.

Chang, T.C. “Theming Cities, Taming Places: Insights from Singapore.” Geogafiska Annaler, vol. 82, no. 1, 2000, pp. 35-54.

Coons, Sam. “Wayfinding in Themed Design: The ‘Weenie.’” Theory of Theme Parks: Memory, Experience, and Design in the Themed Space, 16 August 2015. http://theoryofthemeparks.blogspot.com/2015/08/wayfinding-in-themed-design-weenie.html. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Delany, Samuel R. Times Square Red, Times Square Blue. New York University Press, 1999.

Desmond, Jane. Staging Tourism: Bodies on Display from Waikiki to Sea World. University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Gottdiener, Mark. The Theming of America: American Dreams, Media Fantasies, and Themed Environments. 2nd edition, Routledge, 2020.

Harvie, Jen. Fair Play: Art, Performance and Neoliberalism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Kokai, Jennifer A., and Tom Robson, editors. Performance and the Disney Theme Park Experience: The Tourist as Actor. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019.

Kunst, Bojana. Artist at Work: Proximity of Art and Capitalism. Zer0 Books, 2015.

Lavender, Andy. Performance in the Twenty-First Century: Theatres of Engagement. Routledge, 2016.

Lim, Eng-Beng. “Performing the Global University.” Social Text, vol. 27, no. 4, 2009, pp. 25-44.

Lukas, Scott A., editor. A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces. ETC Press, 2016.

———. “Time and Temporality in the Worlds of Theme Parks.” “Here You Leave Today”: Time and Temporality in Theme Parks, edited by Filippo Carlà, Florian Freitag, Sabrina Mittermeier, and Ariane Schwarz, Wehrhahn, 2016.

Martin, Randy. Under New Management: Universities, Administrative Labor, and the Professional Turn. Temple University Press, 2011.

Medina, Jennifer. “By Day, a Sunny Smile for Disney Visitors. By Night, an Uneasy Sleep in a Car.” The New York Times, 27 February 2018, https://nytimes.com/2018/02/27/us/disneyland-employees-wages.html. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Miller, Hillary. Drop Dead: Performance in Crisis, 1970s New York. Northwestern University Press, 2016.

Mittermeier, Sabrina. A Cultural History of the Disneyland Theme Park: Middle Class Kingdoms. Intellect Books, 2020.

Richards, Kimberly Skye. “Crude Optimism: Romanticizing Alberta’s Oil Frontier at the Calgary Stampede.” TDR/The Drama Review, vol. 63, no. 2, Summer 2019, pp.138-157.

Sacasas, L. M. “Assuming Responsibility for Time.” The Convivial Society, vol. 1, no. 7, 2020. https://theconvivialsociety.substack.com/p/assuming-responsibility-for-time. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Schechner, Richard. Environmental Theater. Hawthorn Books, 1973.

Schweizer, Bobby, and Celia Pearce. “Remediation on the High Seas: A Pirates of the Caribbean Odyssey.” A Reader in Themed and Immersive Spaces, edited by Scott A. Lukas, ETC Press, 2016, pp. 95-106.

Self, Jack. “The Big Flat Now: Power, Flatness, and Nowness in the Third Millennium.” 032C, no. 34, Summer 2018, https://032c.com/the-big-flat-now-power-flatness-and-nowness-in-the-third-millennium. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Souther, Mark. “The Disneyfication of New Orleans: The French Quarter as Facade in a Divided City.” Journal of American History, vol. 94, no. 3, 2007, pp. 804-811.

Symes, Colin. “Selling Futures: A New Image for Australian Universities?” Studies in Higher Education, vol. 21, no. 2, 1996, pp. 133-147.

Tiqqun. This Is Not a Program. MIT Press, 2011.

Velasco, Paulina. “Down and Out in Disneyland: Study Finds Most LA Workers Can’t Cover Basic Needs.” The Guardian, 1 March 2018. https:/theguardian.com/us-news/2018/mar/01/disneyland-california-employees-poverty-homelessness-study. Accessed 13 April 2021.

Wickstrom, Maurya. “Commodities, Mimesis, and ‘The Lion King’: Retail Theatre for the 1990s.” Theatre Journal, vol. 51, no. 3, 1999, pp. 285-298.

———. Performing Consumers: Global Capital and Its Theatrical Seductions. Routledge, 2006.

Williams, Rebecca. Theme Park Fandom: Spatial Transmedia, Materiality and Participatory Cultures. Amsterdam University Press, 2020.