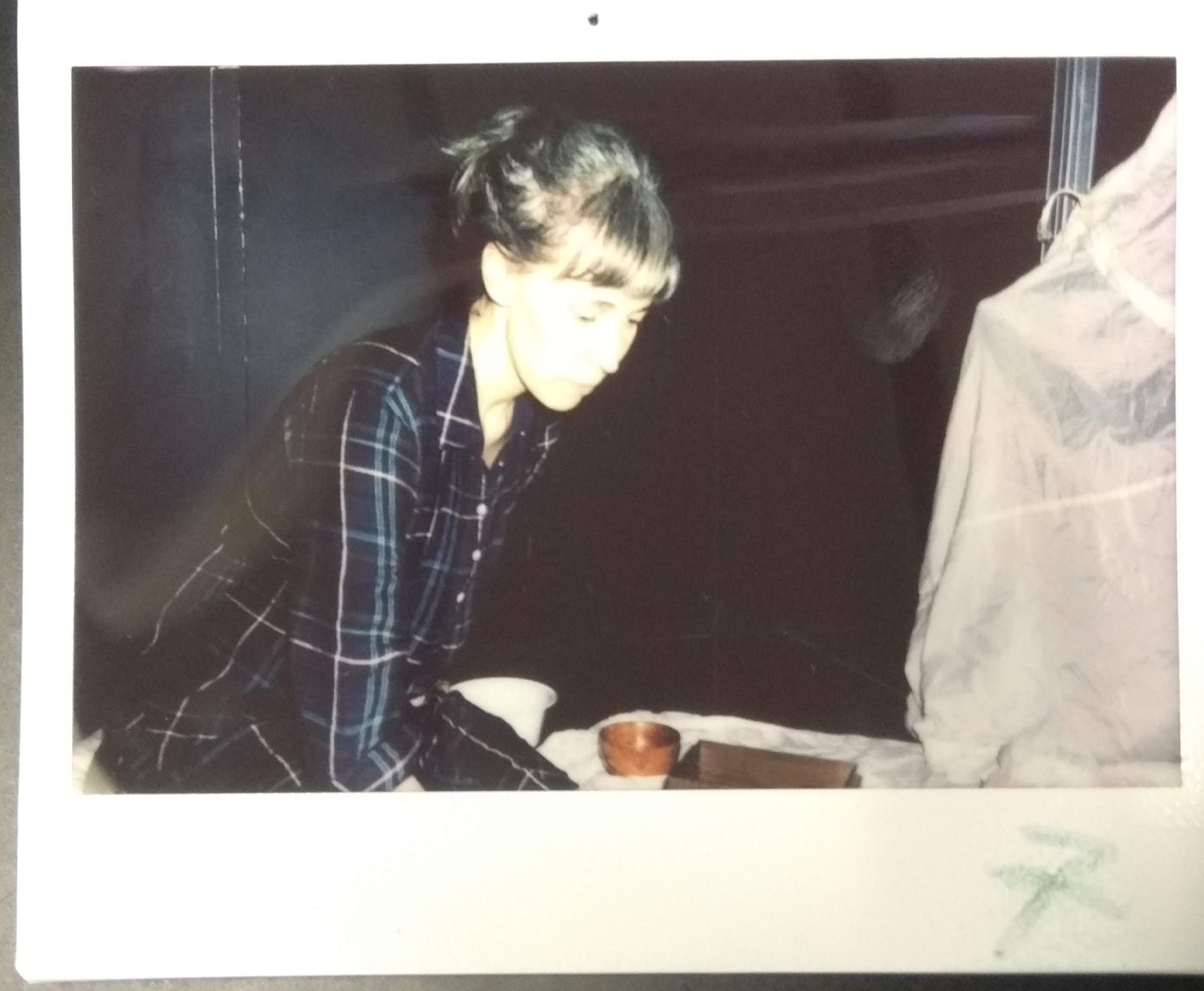

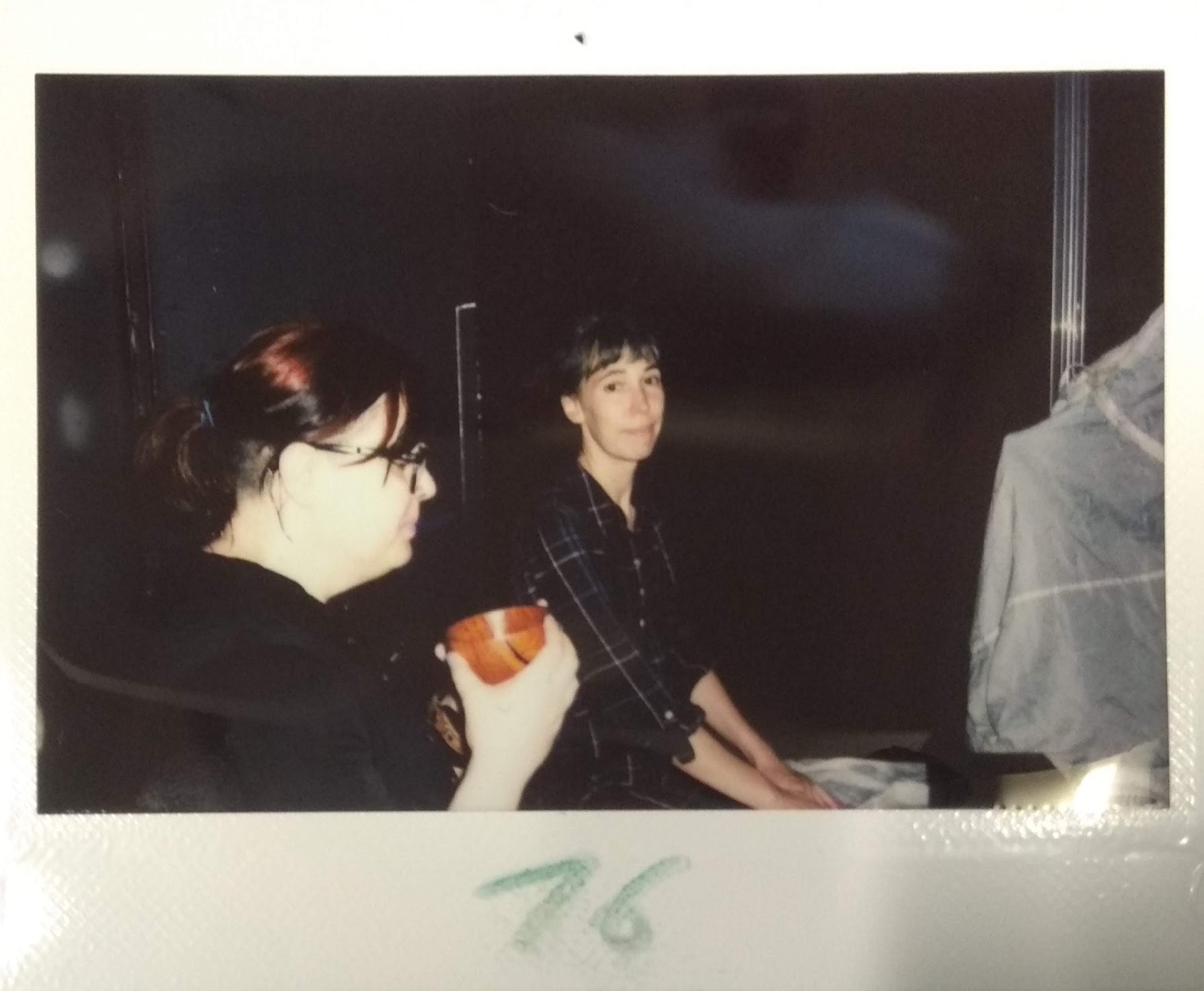

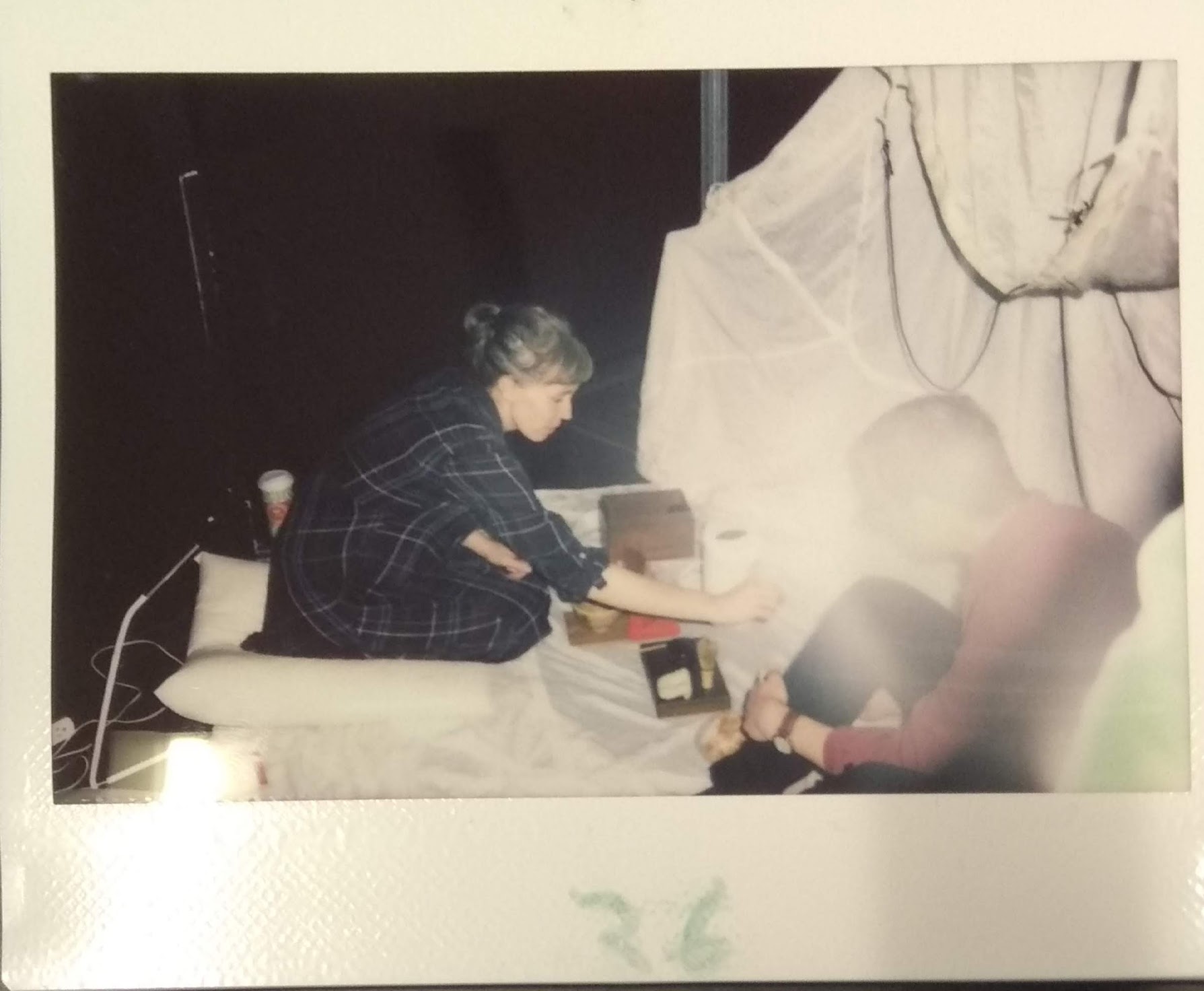

For the 2019 Performance Studies international conference at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, I presented a paper on Japanese “tea ceremony” in a traditional panel format along with colleagues, and I also participated in the “Theme Park” installation, serving tea to one or two guests at a time, using a portable chabako “tea box” and modified utensils, tucked into a parachute tented in a corner of the room. Although I have long intended to write my second academic monograph on the Way of Tea in a performance studies frame, the process of presenting my research and knowledge of tea in these two separate formats, which we could articulate as “theory” and “practice,” raised significant concerns for me in terms of the adequacy of either format to accurately, appropriately, or precisely convey incisive scholarly analysis of Tea practice. My ongoing attempts to translate more than twenty years of Japanese Tea practice on three continents into academic performance studies discourse, in some sense, have highlighted the insufficiencies and contingencies of both theory and practice. In other words, in frustration with the shortcomings of description and analysis I perceived in my own academic paper and presentation, I found myself declaring to an awful lot of people in Calgary that I wouldn’t present on Tea in academic settings anymore. However, as a scholar with a vested interest in failure and a faith in its potentiality to reveal important interventions, even revolutions, in thought, now I’m enticed to revisit my Calgary failures with an eye to figure out what those failures may have to teach regarding limits and possibly new methods of cross-cultural knowledge formation and dissemination.

In the following, I revisit both of my PSi presentations in renewed conjunction with the conference theme of “Elasticity” to attempt to chart a way through or around some of the inflexibilities of our typical academic structures as well as inflexibilities in contemporary notions of “cultural identity” and “traditional cultural practices.” I employ the underutilized format of theses as one initial means of easing typical strictures of academic essay writing. Excerpts from the conference paper I delivered in Calgary appear in this text as Arial font block quotes.

I am looking to focus on two primary sets of tensions within my work on Tea which could be usefully articulated within the metaphor of elasticity; one is a structural tension in the methods and modes of trying to intellectually analyze and elucidate Tea for the academy. I find myself, more than in any other research project of mine, torn by the recurring disconnect between “theory” work and “practice” work (graphically demonstrated in my two Calgary presentations). How and why is it that in theater and performance studies reasoning, performance or embodied work is often implicitly relegated to a secondary position after textual intellectual reasoning, even as we pay continuous lip service to performance as prior to and often the inspiration for our academic work? Tea practice itself inherently contains some discourse on this perennial divide: a paradoxical promise of expansive mentality constituted through the restriction of physical movement. Secondly, I am interested in the stretchiness of seemingly rigid concepts like “cultural identity” (an elasticity which I will contend is borne out through performance) and the narrowness of seemingly capacious ones like “mindfulness,” further complexities which I will contend can be usefully articulated through the examination of Tea practice.

PART 1: Theses on Tea as Embodied Knowledge Acquisition and Scholarship

Thesis: The embodied practice of Tea is hard to translate to text, and is in some sense diminished by the translation

Here’s the real problem I have with presenting tea research: every academic paper becomes a primer on What is Japanese Tea? 101. I can never get on to the insights I want to reach or the knotty intellectual problems I want to work out, because there’s a limited audience who can meet me there, and I can’t go far enough along the path to get more people there in twenty minutes or less. So, what do you need to know to follow an argument about Tea and the formation of cultural identities?

*

If you are not familiar with Chanoyu or Chado, you might be privately wondering, like my mother did about five or seven years into my studies, don’t you KNOW how to make tea yet? My answer is: it’s a physical practice more than a knowledge, like a martial art or yoga. You may know a lot, but, if you don’t actively do it, it’s not really there. In general, the way studying tea unfolds is that one goes to a teacher regularly, typically weekly, and practices procedures called temae, which are the decided and choreographed movements of host, guests, and utensils that culminate in the presentation of sweets and matcha (powdered green tea) to guests by host. There are many different variations on how the tea gets to the guest(s) varied by seasons, combinations of utensils, occasion, and fun. There are two ways to prepare matcha: thick and thin (koicha and usucha) and many practitioners consider the true culmination of study to be the event called chaji: the preparation and presentation of fire for hot water, a kaiseki meal, sake drinking, thick tea and thin tea, with an “intermission” rest called nakadachi in the middle. In practice, a large proportion of tea practitioners only do tea at weekly lessons rather than do chaji, and primarily focus on learning thick and thin tea procedures, rather than studying the cooking, serving, fire-laying, and room-preparation entailed in chaji preparation.

*

The movements of temae (tea-making procedure) are basically learned like dance choreography and can appear to be elaborately superfluous to the actions of simply making a bowl of tea for someone else, although practitioners will tell you they are the same actions as you would take in your kitchen, only exhaustively articulated out to make every unthought movement and gesture into a conscious one.

Study is thus a process that takes years to master, and, to be clear, no matter how masterful one becomes, still in carrying it out most people make mistakes in any given temae. (You could imagine it like figure skating, perhaps: the greatest athletes also miss combinations.) Study of tea encompasses both bodily deportment and a panoply of knowledge and lore, in written and orally transmitted combinations.

関

Tea practice fits into a genre of practices that might be called “hobbies” in English and indeed are sometimes called hobbies in Japanese (shumi 趣味), too. However, they are also often considered shugyō (修行), practices of self-cultivation. The notion of shugyō is applied to many artistic bodily practices in Japanese culture, especially those infused with reference to Zen Buddhism, like martial arts and Noh theater, to explain (and elevate) the depth and seriousness with which these embodied forms are taken.[1]

Shugyō elicits associations with an overarching Japanese cultural value on doing (potentially mundane) things extremely well, or thoroughly, that tends to draw much admiration as a national trait in international contexts. In this sense, shugyō might be compared to the appreciation of shokunin (職人) — craftsperson — expertise in otherwise inglorious occupations, like artisan manufacturing or food service such as sushi-making or ramen noodle cooking, as attested to in the 1985 feature film Tampopo, the 2011 documentary Jiro Dreams of Sushi, as well as the Michelin guide[2] and innumerable international-food shows.[3]

*

To be clear: I am not arguing that Japan is a magical land of experts and connoisseurs; but I am trying to draw attention to a nebulous cultural value (by no means a ubiquitous one) that is also prized, and therefore perhaps sometimes disproportionately emphasized, in foreign discourses on Japanese culture. And Tea authorities and ambassadors tout these values of care and thoroughness because they are ideals of the practice and excellent PR. They also might often be true of Tea practitioners, although it remains healthy not to confuse an intention with a material achievement.

関

Thesis: The embodied practice of Tea relies on forms of knowledge frequently unintelligible to academic scholarship (wherein I present a personal history that feels self-indulgent and unnecessary to most forms of scholarship, but which I hope will be of use in part 2).

I started studying tea in 1999 when I was finally able to enroll in the popular college course that allowed you to do two semesters of tea study as the fulfilment of Pepperdine University’s “Non-Western Heritage” requirement. By joining the class, I became a student of the Urasenke school of Tea, which traces a patrilineage back to Sen no Rikyu, the man credited as the “father” of wabicha, the Zen-inflected version of tea practice that has become the dominant tradition in Japan today. Urasenke is the largest by practitioner population of a dozen or so active schools and lineages.

*

Before that, when I was about nine years old, there was the passage in the Girl Scout badge book that described the drinking of tea in the “Japanese tea ceremony.” I remember vividly that it described turning the tea bowl in your hands three times before you drink. I don’t know why that was thrilling, but when I was next in the Topeka Public Library, I went to the card catalogue, and I looked up “Japanese tea ceremony,” and there were two or three books. They were in the adult section, and I remember climbing on that squeaky metal stool to reach high up on the shelves. I pulled down the two books, and I surely sat down on the metal stepstool and opened them. There were almost no pictures so, discouraged, I put them away and headed back to the familiar territory of the children’s section. But those three turns of the bowl (update: it’s actually only two; the Girl Scouts were wrong) stuck with me and in 1999 as a college junior, I finally held the bowl in my hands, learned to make the turns, and began to incorporate those practices into my own body.

*

Japan is a country and culture with which I have no genetic or family connection, but after two years of tea study at my undergraduate institution, I moved to Japan to teach English. I lived in a mountain village on the smallest of the four main islands, Shikoku, as an assistant language instructor in a public junior high and elementary school for two years immediately after graduating from college. In 2012-13, I spent another year in Kyoto at an official training and fellowship program for foreign tea practitioners at the Urasenke Gakuen Professional College of Chado.

I actually studied a different school of tea for those two years in Shikoku because there was only one teacher within driving distance of my village. I was a popular addition for my teacher’s Thursday practices: the Foreigner. I was doubly exotic, as an American and as an Urasenke practitioner in an Omotesenke tea room.

(Put a pin in all this for part 2 when it may serve as evidence of something.)

*

To an unpracticed eye, probably the Omotesenke actions I learned in Shikoku looked interchangeable with the Urasenke ones I learned before and for these sixteen years and counting after, but when you’ve been training yourself in the minute details of a finger curve and which foot to step with first, the differences jump out as vast.

関

Thesis: Tea restricts movement to expand mentality (ideally)

So, what does it mean to agree to years of concentrating on the position of one’s fingers as they grasp a lacquered lid, or to follow the Urasenke method for parsing out footsteps across the grid of tatami mats instead of an Omotesenke one? The ideal described by teachers and Tea authorities would be the sort of spiritual attainment described by the notion of shugyō. Through cultivation of the body’s movements, the infinitesimal and usually ignored actions which make up the accomplishment of a mundane interpersonal activity (one person providing for another), the bodies in question are to gain a certain grace and mindfulness. This is the ideal.

関

Thesis: Different bodies result in different embodiments result in different knowledges

Careful attunement to regularization of movement across all participants often highlights bodily differences among practitioners more than sameness (a variation on the arresting differences the trained eye sees between different schools of Tea). More importantly, despite Tea’s popular reputation as elegant epitome of cultural attainment, different bodies doing the same Tea have been perceived differently.

One of the most pronounced distinctions historically has been between male and female practitioners (although the second part of this paper will be about differences in nationality). The twentieth and twenty-first century of Tea practitioners have been predominantly women; however, prior to the late nineteenth century, men were the majority of recognized participants.[4] Even today, there tends to remain a bifurcation in the types of accomplishment recognized for men and women: women (less recognized for their Tea practices over history) have been disproportionately credited with courtesy and social grace, while men have generally been able to reap greater cultural and spiritual capital from their Tea practice.[5]

I briefly gesture to the literature on gendered differences in Tea practice as a precursor to the conundrum to come: the tension between differently racialized and nationalized bodies all performing the iconically Japanese practice of chanoyu under a shared message of world “peacefulness through a bowl of tea.”[6]

関

PART 2: Theses on Cultural Identity Practices

In English, it is always the “Japanese Way of Tea.” “Japanese Tea Ceremony.” “Japanese Tea.” The tea practice of which I am speaking is hard, maybe impossible, to conceive without its nationalist modifier. “Japanese tea ceremony” was early on recognized as an exemplary national practice by both foreign visitors and those Japanese people attuned to recognizing which indigenous practices, people, and things were of interest to foreigners.

The cultural-national modifier is a gift and a curse: it indexes an ethical field of concern (for attending to unequally distributed power in a historically bounded field of global cultural relations) while also obscuring others.

*

関。間。Kan and kan. These two kanji are often pronounced identically, but one means “barrier” and the other designates “an opening” or “space.” That is, they are opposites that are also, paradoxically, the same. In fact, we don’t even need 間 (“opening”) to constitute a paradox; 関 can hold both at once. This kan 関 means barrier, but it is the barrier that is also a gate. It is the roadblock that is simultaneously the point of entry, the location of intercourse, transgression, crossing, communication, meeting. It is the good fence that makes good neighbors by controlling and regulating passage.

*

This kan 関 is used in Zen philosophy and is thus popular as a calligraphed hanging among Tea practitioners, for whom it is a standard to use poetic and Zen calligraphies in tea rooms to set the tone and theme of a gathering.[7]

*

I invoke this kan now to tie Tea’s own Zen leanings to the problem of inducting non-Japanese people into the embodied practice of Japanese culture. To be clear, in Japanese, “Japanese tea” is typically called 茶道 chado or 茶の湯 chanoyu (“the way of tea” or “hot water for tea” — nothing about national identity), but the practice doesn’t need national signifiers to maintain a privileged vantage as a paragon of Japanese culture and even Japaneseness. Is the “Japanese” in the terms for Japanese tea a 関 or a 間?

関

Thesis: Tea exposes a curious tension between universality and Japaneseness

In her 2013 book, Making Tea, Making Japan, Kristin Surak argues that “Japaneseness crystallizes in the tea ceremony” (13) and that the laboriously practiced and performed motions of tea making and the very architecture of tea spaces “craft the body into emblematically Japanese positions” (33). The larger takeaway is that tea practice thus amounts to an exemplary process of what Surak calls “nation-work,” a sustained, repetitive practice that instantiates national identity through performative bodily iteration.

*

Surak is a sociologist, and I am a performance studies scholar. Surak looks for the norm and articulates it, and I am limning boundaries and muddied margins.

*

I agree with Surak’s conclusions, but I wonder what such a claim — that Tea practice instantiates Japaneseness — means for the thousands of non-Japanese practitioners of the form. Since the 1950s, the Urasenke school of Tea has engaged in a sustained effort to attract and train non-Japanese students of Tea through the opening of branch offices around the world (primarily in North and South America, Europe, Australia, and China), the support of networks of students and teachers throughout the world, and the Midorikai fellowship program for non-Japanese citizens to study at the Urasenke Professional College of Chado in Kyoto. (This is the program I, too, participated in, which trains approximately eight to ten foreign students per year.) So, what does it mean not only that foreigners are studying “crystallized Japaneseness” but that an established Japanese institution is encouraging and supporting it?

*

Importantly, contemporary Tea discourses fuse philosophico-spiritual ideas with the fixing and realizing of the Japanese national “Thing.” (I’m using Slavoj Žižek’s formulation of “national Thing” via Tavia Nyong’o’s treatment of it in Amalgamation Waltz. Or look at Marilyn Ivy, Discourses of the Vanishing, 6.)

Multiple notable conclusions might be drawn from this lamination of Tea “spirit” and Japaneseness: we might consider how declarations of peaceableness and distinctionless harmony, foregrounded in standard tea explanations and philosophy, are thereby elided with Japaneseness itself, in obvious divergence from actual historical events. We might notice that this discourse of universal peace and oneness also functions as an invitation to non-Japanese participation.

*

I’m getting at two diametrically opposed concepts which nevertheless coexist in suspension within contemporary Tea practice: the Way of Tea as quintessence and apex of Japanese culture, artistry, and identity and/versus Tea’s primary modern PR line, that Tea constitutes a mode of universal communion for all people, a message innovated and promulgated especially by the 15th generation head of the Urasenke school of tea, Sen Genshitsu XV, both through his actions (traveling extensively, donating tea houses to various institutions around the world, sponsoring international teachers and the foreigners training program I participated in) and also through his discourse and slogans. 一碗からピースフルネス (Peacefulness through a bowl of tea — “Peacefulness” is transliterated English) was adopted as a slogan in the early 21st century and is still enthusiastically shared by teachers and students of Urasenke at Tea demonstrations and in classes around the world.[8]

On one hand, this is a message tailor-made for the contemporary moment (read: global neoliberalism). Mindfulness is presented as a personal practice with ambitions (or at least gestures) to public good. Zen combined with consumption of nice things from art works, design, and flowers to outrageously sugary sweets and antioxidant-laden special tea enjoying its own health fad around the world independent of the practice. On the other hand, contemporary Tea discourse is also thoroughly imbricated in the salvage mentality of disappearing native practice marked by scholars, professional and especially amateur, dedicated to “recovering” and “preserving” the venerable history of this endangered art. The training practices of Chado, especially the closer you get to the “center” in Kyoto, are thoroughly quote-unquote “traditional,” involving layers and layers of etiquette, traditional Japanese training structures of a single teacher, and unbroken patrilineal leadership centered on the Sen family.[9]

*

“Without concern for cultural or religious differences, Chado speaks directly to the humanity of people. Without concern for national origins, the spirit of tea enriches all those people who practice it,” read the opening lines of Sen Genshitsu XV’s 1979 book Chado: The Japanese Way of Tea (2).

Tea study, then, offers tiered levels of entry into an ambivalently coded “tea spirit” that oscillates between universal spiritual practice and quintessential Japaneseness through physical and linguistic adoption of Tea’s norms and practices. Perhaps bizarrely, universality seems to become rigid with the constraint of highly codified choreography, while the national-cultural modifier “Japanese” is stretched to accommodate. . . anyone?

関

In a 2013 presentation of my work on Tea, an auditor in Q&A asked if we might think of the practice of Tea by “foreigners” as “deep tourism.” It’s a compelling term, and one that speaks especially to the ways in which, surely, many non-Japanese practitioners are drawn to Tea practice, at least in part, due to its exoticness, even as they (we) also become deeply embedded, entangled, or otherwise naturalized (if you will) to the practice. However, “deep tourism” — a term I repurposed in my paper title for PSi in Calgary — I think also reifies a notion that there may be a non-touristic, “authentic” way to be involved in Tea.

*

The concept of “tourism” suggests that there are places in the world that are “home” and places that are “foreign” wherein you might visit but not actually belong except as a visitor — places and cultures where you belong naturally, without working at it, and places where you do not inherently belong.

*

But there is both “foreign” and “domestic” tourism.

*

What is the elasticity of “belonging,” of “being,” of “being at home”? The work of Tea, as Surak elucidates, is precisely the work of learning to better inhabit an identity assumed to be inborn, stretching individuals to better embody what they’re already assumed to be, and thus potentially — as I am beginning to broach here — stretching notions of Japaneseness to encompass more people not typically deemed Japanese.

*

Let me be as clear as possible here: I am arguing for the primacy of foreignness, not home. I am suggesting that all cultures come to exist as individual “identities” through laborious processes of induction, and I am suggesting that while there are serious political and ethical concerns that may be served through a “strategic essentialism” of nationality, it may be worthwhile to consider if there are other ways to address those concerns that do not rely on the myth of essentialism.

And if we’ve dispensed with essentialist notions of identity (which I have), then what is it that we are continuing to call to when it’s no longer the notion of an inborn nature that must indelibly out? If it is not nature, then must it be something like nurture? And what is nurture if not repeated, sustained experience? How is that accrued: if not by accident of proximity, then surely by purposeful execution of intention?

*

[This, then, is where my foregoing detour into personal history is offered as a strange and uncomfortable kind of evidence. Strange and uncomfortable because how can youthful curiosity and a suspect acquisitiveness regarding “other people’s cultures” be evidence of anything but (75%) white appropriation, licensed by white power structures of the 1980s? On the other hand, would not the search for other kinds of more rational evidence for how people end up doing what they do, knowing what they know, and loving what they love be necessarily fraught with failure, since people surely do, know, and love irrationally, through accidents, coincidences, and untraceable meanderings?]

*

I’ve studied Tea now for twenty plus years and spent two different stints living in Japan, two years in the deep countryside and one year wearing kimono every day, studying Tea full time and participating in the daily cleaning and meeting routines of the school. More times than I can reliably count during these decades have Japanese people heard about my Tea experience and told me, “You’re more Japanese than I am!” We both laugh at that, because this is clearly and hilariously a joke. However, it’s a joke that indexes the vast unnaturalness that lies beneath identity formation and the cultural queasiness that Tea-as-cultural/national-practice particularly evokes.

関

Thesis: Identity is Cultured

Could just the notion, the indubitable existence, of “domestic tourism” help us to reconfigure notions of essential national culture? Domestic tourism may helpfully illuminate particular dynamics at play in a national culture deeply entangled in essentialist notions of identity — a nation so entangled that an entire subsection of Japanese theory has been entitled nihonjinron (日本人論) “Theories of Japanese Uniqueness.” Japanese and non-Japanese people have colluded for generations on reifying the idea of the fundamental difference of the Japanese — both from other races but also from “other Asians.” Nihonjinron provided a [spurious] justification for Japan’s two “miracles” of modernization: the Meiji period of “Civilization and Enlightenment” which ended in empire-building and world war and then the “Economic Miracle” of post-war commercial reconquest culminating in the 1980s bubble.[10]

Accounts in both English and Japanese often focused on inscrutable Japanese differences (i.e., homogenous selflessness vs American independence) to explain Japanese success on the global stage, rather than their similarities to the European colonial and imperial world-conquerors who came before them.

関

When the call came through for performances for the ElastiCity Theme Park portion of the PSi conference in Calgary, I didn’t think too much about any troubling ramifications of doing Japanese tea as part of a “theme park.” I am accustomed at this point to introductory presentations (“demonstrations” or “demos” as we frequently call them), and this one felt no different and in fact perhaps better, since having a practical element enabled me to offer some context to my paper of the day before. In practice, it was the twenty–minute paper that felt more difficult to situate than making bowls of tea in the corner of the theatre space.

When the call came through to expand our thinking and writing from PSi 2019, it was only after I had begun to write these theses and began receiving feedback that I realized how twenty-first century Euro-American academic habits of thought themselves could constitute an obstacle. The obstacle I encountered in this case was, perhaps ironically, reflexivity. Reflexivity, I contend, is good in scholarship. It requires each scholar to examine the ground on which they stand and account for how that location affects what can be said. Such a scholarly reflexivity, however, must be the beginning of the statement, not the statement itself. Some reflexivities reflect so brightly on their own advantageous position that they congeal into another white solipsism, centering the historical fact of global Euro-American imperialism as the future of knowledge production — a closed kan, occulting any knowledge beyond the fact that Euro-American culture(s) of whiteness have conditioned knowledge (which knowledges have been recognized as knowledge, who can access it, what it means, where it fits).

To be clear: this text is not intended as a denial of the outsized mediating, controlling power of white culture(s) in Anglophone knowledge creation, and this is no defense of that state of affairs. Rather, it is an attempt to notice when certain habits of critique harden into dogmas, which obscure new attempts at knowledge instead of facilitating them. In the foregoing theses, I have worked to elucidate specificities in the case of Tea practice, philosophy, and dissemination which render the model of “empowered appropriator/passive appropriated” inaccurate. To fail to recognize the active and specific strategies taken by Tea authorities over time to calibrate and refine the modes by which Tea travels the globe would be to risk succumbing to a white western solipsism, a dynamic of thinking that perpetuates western hegemony by seeing western hegemony in every exchange.[11] Through attention to specificities, perhaps we may begin to establish new habits of thought that, I hope, will both preserve the ethical concerns regarding appropriation, white-centrism and -supremacy in Anglophone theorizing while also stretching our modes of scholarship toward new realizations, and potentially more capacious (or elastic) understandings of how identities and cultures encompass individuals and are altered, expanded, and evolved by those individuals. Obviously, these few words are only the beginning of one attempt at such an endeavor.

関

My conclusion for now, borne out through embodied and academic textual study, would be this: that nationality, culture, and prestige be recognized as acquired through laborious performative practice, so that “authentic” and “touristic” apprehensions of culture be recognized as differences of degree, not type.

Such an understanding of culture as literally cultured — nurtured into existence with time and effort and appropriate catalysts — is certainly not unheard of, but I think perhaps obscured in the rush to preserve the purity of certain arts and activities from debauched imitation. Tea transmission makes the non-differentiation of the authentic and touristic clearer, as its existence is entirely dependent on performativity — that is, it must be constituted in endlessly reiterated, which is to say, imitated, doings in order to exist at all.

*

So, we might ask ourselves, what is it that recourses to national or cultural purity seek to preserve, and how can we preserve it without reifying a notion of naturalized national culture and identity? For while the habit of intellectually restricting a cultural form to the bodies believed to have “inherited” it serves some ethical purposes, it opens other minefields: like a sense of inadequacy individuals internalize when, inevitably, they turn out to be less “naturally” their own identity than others seem to be; or simply the fallacy of continuing to assume fundamental, unalterable differences in people on the basis of nationality, culture, or race.

*

I hope we can use attention to Tea and other embodied cultural practices to maintain scrutiny and continue to rectify the power differentials exposed by critiques that center cultural expression and cultural appropriation, while continuing to articulate identity as a practice rather than an essence. My suggestion is that chanoyu, due to the curious way in which it makes visible the laborious work of creating national identity, thus emerges as a gate — potentially a closed one, a kan — at which we might begin to articulate this culturing process more precisely.

*

What would it look like to approach this gate and what would it cost to pass through?

関

For more on shugyō, see for example Yuasa 85, 98, 103. ↑

See for example “Tokyo Holds on to Coveted Spot. . . ” or “Michelin Stars Draw Shots,” https://japantimes.co.jp/life/2018/11/27/food/tokyo-holds-coveted-spot-city-stars-2019-michelin-guide/ and https://wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303738504575568442015009552 ↑

For more on shokunin mentality and philosophy, see Russell 394, Cang n.p., Kondo 43. ↑

The standard description of women’s entry into Tea study is succinctly displayed in Sen 8 or Mori 87. ↑

Authors Corbett, Kato, Mori, Surak, and Chiba discuss these historical and current gendered differences in, reception of, and assumptions about male and female practitioners. (See, for example, Corbett 2009, 82; Kato 61.) ↑

See for example the greeting from Hounsai Daisosho (Sen Genshitsu XV) on the official Urasenke English webpage: http://urasenke.or.jp/texte/greetings/greetings.html. ↑

Shimano 1995, 46. ↑

http://urasenke.or.jp/texte/ ↑

Mori 1991, 91. ↑

Sugimoto, Kawamura, Dale ↑

It would not be inappropriate to consider the international outreach efforts of Japanese cultural authorities as also partaking of cultural imperialist motivations, part of both coordinated and nebulous “soft power” inclinations. I treat this angle beyond the world of Tea practice in “No ‘Thing to Wear’: A Short History of Kimono and Inappropriation from Japonisme to Kimono Protests,” TRI: Theatre Research International 43:2 (2018), 165-184. ↑

Cang, Voltaire. “Sushi Leaves Home: Japanese Food and Identities Abroad.” Food Identities at Home and on the Move. Abingdon (UK) and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2020.

Carriger, Michelle Liu. “No ‘Thing to Wear’: A Short History of Kimono and Inappropriation from Japonisme to Kimono Protests.” Theatre Research International, vol. 43, no. 2, 2018, pp. 165-184.

Corbett, Rebecca. Cultivating Femininity: Women and Tea Culture in Edo and Meiji Japan. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2018.

Corbett, Rebecca. “Learning to be Graceful: Tea in Early Modern Guides for Women’s Edification.” Japanese Studies, vol. 29, no. 1, 2009, pp. 81-94.

Dale, Peter. The Myth of Japanese Uniqueness. New York: St Martin’s Press, 1986.

Ivy, Marilyn. Discourses of the Vanishing: Modernity, Phantasm, Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995.

Kato, Etsuko. The Tea Ceremony and Women’s Empowerment in Modern Japan: Bodies Re-Presenting the Past. London and New York: Routledge, 2004.

Kawamura Nozomu. “The Historical Background of Arguments Emphasizing the Uniqueness of Japanese Society.” Social Analysis: The International Journal of Anthropology, vol. 5, no. 6, Dec. 1980, pp. 44-62.

Mori, Barbara Lynne Rowland. “The Tea Ceremony: A Transformed Japanese Ritual.” Gender and Society, vol. 5, no. 1, Mar. 1991, pp. 86-97.

Nyong’o, Tavia. The Amalgamation Waltz: Race, Performance and the Ruses of Memory. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

Russell, Stanley. “Apprenticeship with a Shokunin a Search for the Source of Quality in Japanese Architecture.” Fresh Air: ACSA Proceedings. 2007, pp. 393-398. http://acsa-arch.org/chapter/apprenticeship-with-a-shokunin-a-search-for-the-source-of-quality-in-japanese-architecture/. Accessed 14 April 2021.

Sen Genshitsu XV. Chado: The Japanese Way of Tea. New York and Kyoto: Weatherhill / Tankosha, 1979.

Shimano, Eido Tai, and Kōgetsu Tani. Zen Word, Zen Calligraphy. Boulder: Shambhala, 1995.

Sugimoto, Yoshio. “Making Sense of Nihonjinron.” Thesis Eleven, vol. 57, no. 1, 1999, pp. 81-96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513699057000007.

Surak, Kristin. Making Tea, Making Japan: Cultural Nationalism in Practice. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2013.

Yuasa, Yasuo. The Body: Toward an Eastern Mind-Body Theory. Translated by Shigenori Nagatomo and Thomas P. Kasulis, Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987.

Žižek, Slavoj. “Eastern Europe’s Republics of Gilead.” Dimensions of Radical Democracy, edited by Chantal Mouffe, London and New York: Verso, 1992, pp. 193-210.