University of the Arts Helsinki

In this article and video essay I am exploring alternative versions of presenting a video essay, partly inspired by the notion “dense video” suggested by Ben Spatz (2017), partly by previous attempts.[1] Contrary to my initial plan I have not “densified” the video essay by adding subtitles and references to the images on video. As a compilation of several video works inserted into each other and an added voice-over text it seems to be rather dense as it is. The density in this case is not created by references and quotations, nor only by the spoken text, but by the variations or “diffraction patterns” produced by combining and inserting related videos and performances for camera into one-another and next to one-another. In order to make the “self-diffraction” thus produced more explicit, two versions of the video essay are presented; the original version with a voice-over text as well as the same compilation of works as a visual essay without added text. I have also included some still images to accompany the transcript of the voice-over text. This is done to give a reader who prefers to read a written text with illustrations rather than to listen to a text supporting a video the possibility to choose that option. In order to give more prominence to the video compilation as such I have included a visual version of the video essay without a voice-over text. This way I hope to make the self-diffraction (or diffractive practice) in the video works more easily recognizable, to provide the possibility to enjoy moments of silence with more focus on the images for those who prefer that option, and to open up the idea of what constitutes a video essay for those who expect it to fit in with the genre of the film essay.

While creating the works I did not think in terms of diffraction, but rather of repetition with variation. Theory was brought to the work after the fact, as is common in forms of research were practice rather than theory provide the starting point. Rather than “explaining” the practice, however, there is an attempt at theorizing from and with the practice, interweaving the experiences of performing with the theories of Barad (diffraction), Jones (self-imaging) and others. This is done in order to generate a new notion, “self-diffraction,” which might actually be more useful for understanding other types of practices than the one presented here, although it sprung out of that practice.

The question of the power of concepts (“does it make a difference if I call it self-diffraction?”) and of the apparatuses or material-discursive practices we use and are used by, would be a topic for an essay on its own. In this context, however, the question is almost rhetorical, like a moment of self-doubt — what difference does it make? Although I am not answering that question in any concrete way, I would like to hope that it makes a difference. The terms we use are part of the apparatuses that determine what we look at and how, because those “apparatuses are the exclusionary practices of mattering through which intelligibility and materiality are constituted” (Barad 2003, 820), and therefore what can be seen.

Enough of disclaimers and explanations; now I invite you, dear reader-viewer, to try out for yourself how these versions — the text, the video essay and the video essay with the spoken text — communicate to you “self-diffraction as a strategy.”

Transcript of voice-over text:

In this video essay, I will experiment with the format by creating a remix of artworks and reflections in a spoken commentary. By using a video recording of a revisit in 2018 to the site where the video work Year of the Rat — Mermaid was performed during the year 2008 as a base, I combine variations of the work as well as ideas related to it later, with a focus on “self-diffraction,” a notion I develop from diffraction as used by Karen Barad (2014). The main question is: What is the pedagogic, political or therapeutic potential in such “self-diffractive” rather than self-reflective exercises?

This revisit is part of the research project How to do things with performance? where one of my tasks has been to explore what can be done by returning to my twelve-year project “Performing Landscape” (2002-2014), based on the Chinese calendar. For the year of the rat, in 2008, I took the sculpture Den Lille Havefrue or The Little Mermaid as my starting point, posing weekly on a rock on Harakka Island in Helsinki in a position resembling the statue in Copenhagen, inspired by the fairy tale “The Little Mermaid.” Variations of the pose were repeated along other shores, including next to the statue itself, during her 95th birthday, accidentally.

The notion “self-diffraction” is here proposed as a notion to describe these variations, an interference pattern of multiple versions of the self. In these examples self-diffraction is rather subtle, like imitating the body posture of the sculpture and referencing the fairy tale through bare feet, combined with responses to the specificities of each site. The simplest form of diffraction comes into play through repetition; there is no one image, no one representation repeatedly reflected, but an almost endless wave of variations.

In a presentation during a research day on performance pedagogy,[2] organised by the How to do things with performance -research project, I presented a record of a revisit in august 2018 to the rock where the video work Year of the Rat — Mermaid was performed during the year 2008. Besides examining ideas related to the work in texts I wrote a few years later, such as choosing silence, or affirmation as a strategy (Arlander 2012) I asked whether there was any pedagogic, political or therapeutic potential in such self-reflective or rather “self-diffractive” exercises? That presentation served as a starting point for this experiment.

In the Academy of Finland funded four-year research project How to do things with performance? we have explored, together with Hanna Järvinen, Tero Nauha and Pilvi Porkola, what can be done with performance; what actualizes when a performance takes place, when it is documented, and when it is written about? In that context I have returned to my twelve-year project “Performing Landscape” from 2002 to 2014 and the resulting series of video works called Animal Years and Animal Days and Nights, with each year named after the animal in the Chinese calendar. The project was documenting the changes in the landscape in one particular place, on Harakka Island in Helsinki Finland, during twelve years, as well a day and a night in the same place each year. By using a static camera on tripod, the project combined approaches from performance art, video art and environmental art, and inevitably had an autobiographical dimension as well. The final video works are not pedagogical in any obvious sense and do not offer a chance to participate directly, but could hopefully function as an encouragement for the viewer to “try this at home”, and to develop performative practices of their own.

By returning to the sites on the island where the weekly performances took place during the years 2002-2014 and recording my revisits, I have created basic images using contemporary technology into which the old video installations can be inserted, in miniature. Thus, I have formed video compilations, beginning with the first and last year, the year of the horse (2002 and 2014) at the kick off seminar of the project in the autumn of 2016.[3] Now the turn has come to year of rat, the seventh year in the series. On 11 of August 2018 I visited the rock I sat on ten years earlier, and tried to recreate approximately the same framing as the one used in Year of the Rat — Mermaid, performed once a week before sunset in the year 2008. I used the sculpture Den Lille Havefrue as my starting point, posing weekly on the northern shore of Harakka Island in a position resembling the statue in Copenhagen.

The two-channel video work Year of the Rat — Mermaid 1 -2 (2009), edited of those performances for camera, is here inserted into the recording of the revisit. A synopsis in the Finnish media art archive reads as follows:

Part 1. (right) With a lilac scarf on my shoulders I sit on a rock on the Northern shore of Harakka Island approximately once a week before sunset between 26 [January] 2008 and 24 [January] 2009. Part 2. (left) I sit on a rock further away from the camera on the same occasions.[4]

Day and Night of the Rat — Mermaid (11 min 10 sec.), with the following synopsis, was performed on the same rock, and is here added to the mix:

With a lilac scarf on my shoulders I sit on a rock by the northern shore of Harakka Island every two hours after the winter solstice for a day and night from 22nd December 2008 at 4 p.m. to 23rd December at 2 p.m.[5]

At the time I wanted to play with a sculpture as inspiration, and chose the iconic figure of the little mermaid in Copenhagen, thinking it would be easily recognisable. The fairy tale The Little Mermaid, written by the Danish author Hans Christian Andersen in 1836,[6] translated into English in 1872, and later made famous by Walt Disney, among others, served as inspiration for the sculpture by Edvard Eriksen, who used his wife Eline as a model. The sculpture was a gift to the city of Copenhagen from brewer Carl Jacobsen. It was placed on its site at Langelinie on 23 August 1913 and soon became an important symbol of the city.

When I reread the fairy tale, I realised choosing silence is a central theme in the story where the little mermaid exchanges her tongue and her voice for a pair of human feet, not only because of her love for a human man, but also for the hope of acquiring an immortal soul like a human being. Is this what I am doing in my performances for camera? That was one of my questions in a text written later, “The Salt Basins at Santa Maria — Non-places and the Challenges of Performative Research,” first published in Finnish in 2012,[7] and later in English.[8] There I used another version of the work made on Cape Verde, called Sal 1 and 2, as an example. I wrote:

Artworks form a substitute for immortality; they remain as the traces of our performances. By choosing to perform for a camera in a deserted and rather distant place, I am exchanging the live encounter with an audience for the dream of a digital afterlife, an immortality of sorts. By choosing to remain silent, I am letting go of the need to express my own experiences of the landscape in order to give space to the interpretations and projections of a potential viewer confronted with the images. In that sense, there is a connection between the little mermaid who exchanges her tongue and her voice for a pair of human feet, and me exchanging my voice or my words for a dream of an eternity of sorts. Performances are ephemeral and disappear, while images remain — at least for a while. (Arlander 2012, 393)

In terms of feminist critique, much could be read into a story where only the love of a man and marriage will guarantee an immortal soul for the beloved wife, I added. And it could be expanded in terms of de-colonial efforts as well. What sacrifices are needed for somebody to be allowed to participate in so-called civilized society? Today, I wrote at the time, the idea that mermaids and other sea creatures could obtain an immortal soul through good deeds is perhaps the most fascinating one (Arlander 393), but left it at that. Perhaps, like so many others today, I am pursuing a dream of some form of digital immortality. Performing landscape, however, is not performing the self only. Performances that involve imagining sharing existence with other forms of life were not my main concern then. At the time, I focused on Amelia Jones’ concept self-imaging, Barbara Bolt’s performative research paradigm and Marc Augé’s notion of nonplaces.

“Every story is the silencing of another one. Every image that is created is covering the ones that were not made” (Arlander 390). That is also a question of self-reflection: “One of the tasks proposed for artists engaging in research is to articulate or make explicit the tacit knowledge involved in the production of art” (Arlander 394). Because many aspects of artistic work are at least partly unconscious, the task can be more challenging than it seems. “Simple skills can be hard to translate into discursive language if they have become automatic and, thus, unconscious and are experienced as intuitive knowing. And how does one identify which aspects of the tacit knowledge involved in each specific case are relevant or even possible to clarify, articulate and reflect upon?” (Arlander 394). But, choosing silence is, after all, the opposite of knowledge production.

Another text related to these works, “Performing Landscape as Affirmative Practice” from 2012 (Arlander 368-376) is perhaps more relevant in the context of pedagogy. There I begin by referring to Rosi Braidotti’s text “Affirming the affirmative: On Nomadic Affectivity” from 2005/2006, and to an interview with Elisabeth Grosz in 2007, where Grosz explains why she avoids critique:

I’ve made it a policy for quite a while to avoid critique. Critique always affirms the primacy of what is being critiqued, ironically producing exactly the thing it wants to problematize. But more than that, critique is a negative exercise. It is an attempt to remove obstacles to one’s position. It is really difficult to continue work only on material that you don’t like, or that’s problematic or oppressive. (Grosz qtd. in Kontturi and Tiainen 255)

After discussing how to move beyond patriarchy, she concludes:

We need to affirm the joyousness of the kind of life that we are looking for. The joyousness of art, the pleasure of thought, feminism needs to return to something that makes it feel happier as well as productive. Joy, affirmation, pleasure, these are not obstacles to our self-understanding, they are forms of self-understanding. /–/ The only way we can make a new world is by having a new horizon: And this is something that art can give us: a new world, a new body, a people to come. (Grosz qtd. in Kontturi and Tiainen 256)

But what could this mean in practical terms? One way is of course performing something, or with something, affirming it by focusing on it, attending to it, giving it attention.[9]

In the context of performance pedagogy, it sounds provocative to speak of the advantages of being an auto-didact. By pointing to the advantages of being a self-taught performance artist,[10] I do not claim that they are more numerous than the disadvantages, but rather suggest that there is some value in the tradition within performance art of creating your own methods, making your own mistakes, and sometimes even indulging in being unskilled — all more or less illusionary aspects — that might nevertheless be important counterpoints in the context of pedagogy. There is a tradition to speak of performance art as something that cannot be taught, as discussed for instance by Tero Nauha (2017, 61-70). The point is rather that performance art can and must be reinvented by the one who practices the form. And that is probably why it has such a great pedagogical potential, as suggested by Charles Garoian in his early work in 1999. One could say that the mainstream of performance art is centered around subjectivity, and that is perhaps the main connection to performance art remaining in my work. There is not much ordeal involved in sitting on a rock, despite the repetition.

Self-reflection is one of the skills emphasized in the training of artists and artist researchers alike. And reflexivity is of course a core value in much social science research. Referring to Donna J. Haraway’s critique of reflection physicist and queer theorist Karen Barad has endorsed her proposal of diffraction as an alternative methodology. While diffraction is used by Haraway as a counterpoint to reflection, for Karen Barad it is, among other things, “a tool for thinking about social-natural practices in a performative rather than representationalist mode” (Barad 2007, 88). In classical physics diffraction is understood as the result of the superposition or interference of waves (Barad 78-79) while in quantum physics diffraction experiments are “at the heart of the ‘wave versus particle’ debates about the nature of light and matter” (Barad 72-73). They have shown how “wave and particle are not inherent attributes of objects, but rather the atoms perform wave or particle in their intra-action with the apparatus” (Barad, 2014, 180).

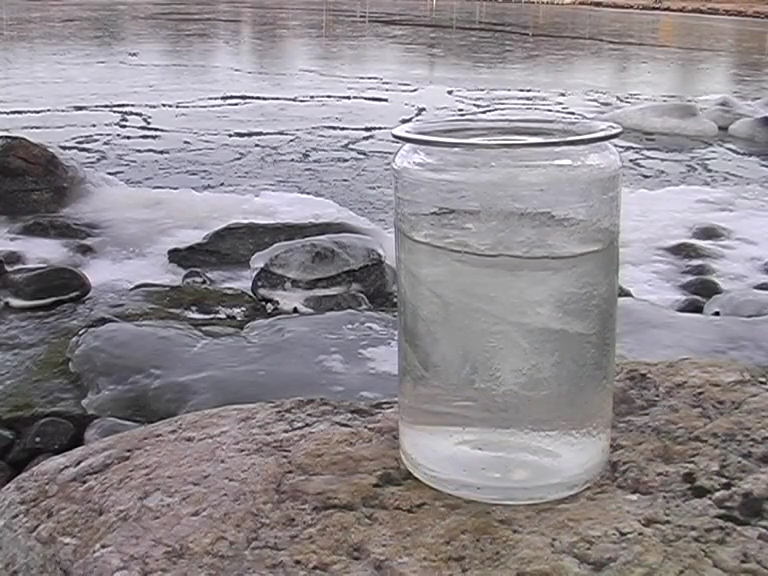

During the year of the rat I made another work on the same site which has more recognizable links with performance art, Year of the Rat — Dripping (short) (6 min. 47 sec.) The title probably brings to mind event scores by George Brecht,[11] although I did not actively consider that while choosing a simple action that could be repeated in a cyclical way and edited into a continuous repetition. While performing, I increased the number of jars filled with water and emptied back into the sea each week until halfway into the summer and then decreased them again.[12] The short version shows only one jar of water for each image. The synopsis reads as follows:

With a lilac scarf on my shoulders I stand in the sea, take water in a jar and pour it back to the sea on the northern shore of Harakka Island approximately once a week before sunset between 26th January 2008 and 24th January 2009. [13]

In her seminal text from 2003, “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter”, Barad explains:

Moving away from the representationalist trap of geometrical optics, I shift the focus to physical optics, to questions of diffraction rather than reflection. Diffractively reading the insights of feminist and queer theory and science studies approaches through one another entails thinking the “social” and the “scientific” together in an illuminating way. What often appears as separate entities (and separate sets of concerns) with sharp edges does not actually entail a relation of absolute exteriority at all. Like the diffraction patterns illuminating the indefinite nature of boundaries — displaying shadows in “light” regions and bright spots in “dark” regions — the relation of the social and the scientific is a relation of “exteriority within.” This is not a static relationality but a doing — the enactment of boundaries — that always entails constitutive exclusions and therefore requisite questions of accountability. (Barad 2003, 803)

In 2014, in “Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart”, Barad writes: “Diffraction is not a set pattern, but rather an iterative (re)configuring of patterns of differentiating-entangling.” Therefore, “there is no moving beyond, no leaving the ‘old’ behind.” According her “no absolute boundary” exists “between here-now and there-then.” “There is nothing that is new” she writes, and “there is nothing that is not new” (Barad 2014, 168).

Barad further explains how diffraction, rather than a singular event, is “a dynamism that is integral to spacetimemattering.” Time “is diffracted, broken apart in different directions, noncontemporaneous with itself. Each moment is an infinite multiplicity.” According her “‘Now’ is […] an infinitely rich condensed node in a changing field diffracted across spacetime” in an “ongoing iterative repatterning” (Barad 169).

Helen Pritchard and Jane Prophet (2015) have used diffraction as a tool in exploring the controversial relationship between mainstream contemporary art and new media art, proposing the term “diffractive art practice,” for their entanglements. Although my practice produces digital video works, I am not proposing to use that term to describe my work. Rather, I am interested in how they describe diffraction as a methodology. Pritchard and Prophet borrow the notion from Barad, who “introduces the optical metaphor of diffraction for re-thinking the relationship between entities and agencies that emerge from scientific practices” while they use it to theorize “knowledge that emerges from art practices” and to demonstrate how such practices “continuously reconfigure the boundaries between them” (Pritchard & Prophet n.p.). The physical phenomenon of diffraction refers to the ways that waves of water, light or sound combine when they overlap, or “the process of bending and spreading out that occurs when waves encounter obstructions” (Pritchard & Prophet n.p.). They use “the example of ripples that appear when stones are dropped into a pond, where dynamic and overlapping ripples change one another’s form” to emphasize that “diffractive patterns are always in movement” (Pritchard & Prophet n.p.). They also note that “reflection […] might be to ‘look back onto’ arts practice,” while “diffractive patterns manifest through reading practices through each other” (Pritchard & Prophet n.p.).

In some sense I am of course looking back onto a practice here, in a self-reflective manner, but also looking at several variations of that practice through each other. What I try to explore is whether a concept like diffraction or self-diffraction could be generative in relation to this particular practice.

In new materialist discourse thinking diffractively can imply a self-accountable, critical, and responsible engagement with the world, while reading diffractively can mean reading texts through one another to produce unexpected outcomes, as suggested by Geerts and van der Tuin. Rather than such a “boundary-crossing, trans/disciplinarymethodology,” which is “blurring the boundaries between different disciplines and theories to provoke new thoughts” (Geerts and van der Tuin, 2016), my understanding of diffraction here is more modest and perhaps more literal.

Examples of posing on various shores, could serve as an example of further “ripples” or “bendings,” or “interference patterns,” diffractions produced by shifting circumstances. The synopsis for a collection of them in Mermaid Variations 1-9, a three-channel installation (3 min 58 sec.) reads as follows:

With a lilac scarf on my shoulders I sit by the sea or in the water in different locations around the world. A. (left) “Mermaid Variations 5-4-7”: Jeju, Jeju, Jeju. B. (centre) “Mermaid Variations 2-6-9”: Kadermo, Jeju, Jeju. C. (right) “Mermaid Variations 1-3-8”: Bergen, Cape Verde, Cape Verde.

These examples from Jeju island between Korea and Japan, Kadermo, a small island in the Finnish Archipelago, Bergen, a city on the Atlantic coast in Norway and Cape Verde Islands west of Africa are spanning from warm to cold seas. Here only six of them are shown, due to time constraints.

In “Thinking through picturing” (2015) Sofie Sauzet interprets diffraction and Barads agential realism for educational purposes. She explains how Barad’s agential realism as a methodology “is about creating reality, not reflecting it” (Sauzet 39). Sauzet describes her “construction of a ‘diffraction apparatus’ to allow students to work with an emergent feminist materialist inspired concept […] through situated practices” and her understanding of “concepts as material-discursive practices that emerge as phenomena in complex practices” (Sauzet 41). Her diffraction apparatus in the context of her pedagogical practice, consists of an assignment of snaplogs (snapshots and notes describing them) and interviews. Sauzet explains how the “the central idea is that ‘the thing’ ‘we’ […] research, is enacted in entanglement with ‘the way’ we research it.” She understands diffraction as “the process of ongoing differences,” in contrast to reflection, which “invites images of mirroring” and maintains that “diffraction helps us attend and respond to the effects of our meaning-making processes,” such as, “how answers emerge from questions, or how analyzing through particular interests makes particular aspects come to the fore and leave others out.” Thus, for her “diffraction is the practice of making differences, of enacting worlds by being in the world.” According her “diffraction can attune us to the differences generated by our knowledge-making practices and the effects these practices have on the world” (Sauzet 41-42).

An open understanding of diffraction as a making of differences, of variations, could be combined with the notion of self-imaging developed by Amelia Jones, which I have discussed in relation to similar works before, or rather, they could be looked at diffractively through one another.

In her book Self/Image — Technology, Representation and the Contemporary Subject (2006), art historian Amelia Jones discusses images and projects that are not “self-portraits” in the traditional sense, but which enact the self (often of the artist her- or himself) within the context of the visual and performing arts (including film, video and digital media) and participate in what she calls “self-imaging” — the rendering of the self in and through technologies of representation (Jones xvii). Jones focuses on images by artists who explore the capacity of the self-portrait photograph to foreground the “I” as other to itself (Jones 43). However, not only exaggerated examples of theatrical, photographic self- production, but in fact all images work reciprocally to construct bodies and selves across the interpretive bridges that connect them, as Jones (43-44) points out. According to Jones, representation, especially in its photographic (and digital) variants, preys on our desire for the body to remain suspended in time forever. There is an urge built into all representational practices involving images of the body to delay or foreclose on death; “self-images — renditions (in some form) that the maker has forged involving his or her own body — make this profound paradox of representation explicit,” she writes (Jones 245).

Combining self-imaging and diffraction we get self-diffraction (which is also an optical term, that I am not referring to here). At a basic level it could simply mean a mode of diffracting rather than reflecting the self in self-imagery. By developing diffraction into something that I call self-diffraction, as an alternative to self-reflection, I am proposing to explore what such a change of terminology could lead to.

These videos are perhaps not the best possible example of self-diffraction, because the basic pattern is one of repetition. It is not a repetition in the sense of a copy, a reflection, but a repetition with a difference, reverberating variations that resemble the interference of waves. The repetitions over time, once a week, approximately, create some form of ripples of the previous action. And showed together they mix and entwine with the other variations and the more recent recording on the site. These repetitions could be understood as a form of self-reflection as well, but something changes with the multiple reverberations, that I would like to call self-diffraction.

Based on these examples I suggest that self-diffraction could be understood as self-multiplication with variation, a diffracting or bending in the face of an obstacle or model, a mixture of a fictional character and self, or self in response to context in different spatial and temporal dimensions, here and there, then and now, again and again.

Besides sitting on various rocks and other shores, I was also posing next to the statue Den Lille Havefrue in Copenhagen, the “original site” as it were, which was in no way the origin or end, as it looks like here, inserted towards the end, but one bend along the way. This was during her 95th birthday, accidentally, after the Performance Studies International conference in Copenhagen in august 2008.[14] The resulting video combines two moments of posing, one at day time and another moment later in the evening. The synopsis for the video The Little Mermaid — 95th Birthday(10 min 5 sec.) is brief: “I’m sitting next to the statue of the Little Mermaid in Copenhagen on ‘her’ 95th birthday.”

Concerning the notion “self-diffraction” we could ask whether various forms of role playing or identity games could be more obvious examples of self-diffraction, creating interference patterns of a multiplicity of dispersed versions of the self. In my examples experimentations with self-diffraction are rather subtle, consisting on one hand of an imitation of the body position of the iconic sculpture of the little mermaid in Copenhagen, and referencing the fairy tale of the little mermaid through the bare feet. And on the other hand of a division into the “observing self” on the rock in the foreground looking at a “posing self” appearing on a smaller rock further away. A third diffractive dimension, and perhaps the most important one, comes into play through the repetition with variations — there is no one image, no one reflection, not one true representation, that is repeated, but instead an almost endless wave of variations or diffraction… including the day and night, the dripping and so on. This is further accentuated by all the variations created with the same scarf and the same pose in other places, bending for obstacles on other shores.

In these works, my way of doing things with performance is first of all based on repeating an action or a pose in the same place once a week for a year, then returning to that site ten years later, trying to repeat the same framing (not really possible) and the same action (not really possible). Rather than as a form of self-reflection, I would like to think of this returning and revisiting, too, as a self-diffraction of sorts, a doubling or overlapping, an ongoing process. As Barad notes, “there is no moving beyond, no leaving the ‘old’ behind” and “no absolute boundary between here-now and there-then” (Barad 2014, 168). When repeating a variation of the action in other places, adjusting to those places, again and again, there is a literal bending, shifting and even spreading out of the pose, the position and the composition taking place.

But, can we speak of performance here? How malleable should our understanding of performance be? Here I understand performance as an action or a pose and a process, which does not necessarily involve imitation, accomplishment or an audience, although the camera on a tripod serves as a witness of sorts and posing with the statue as a model involves some form of imitation and attempted accomplishment. The act of sitting on a rock or something similar could be seen as a minimum of a performance, even a non-performance, but of course there is a series of performances surrounding it, if we think of all the actions involved in one session, on one particular day, like getting to the site, preparing the camera and so on. What you see is only brief fragments of my repeated posing and in some sense the performance is created in the repetition, in the diffraction patterns and their combination. But what about the one-off variations, where I sit on a shore only once in each place, albeit in shifting circumstances? Those sites are overlapping with the scarf and the pose in various ways, combined and diffracted in relation to the other sites as well as to the other figures.

We can perhaps understand context as a form of apparatus, which does things, produces diffractions; “given a particular measuring apparatus, certain properties become determinate, while others are specifically excluded” (Barad 2007, 19). The shift of context between the performances in one place from one time to the next, between the site returned to and the sites visited only once, between the singular moment and so on, including the showing and viewing of this video compilation, could be thought of in terms of representation — what does this suggest — and in terms of production — what does it lead to? Here I have suggested to think of them in terms of entanglements and process, of differentiation, of diffraction. The context on Harakka Island in 2008 and in 2018 allowed different actions and produced different effects, as did the context on Langelinie in Copenhagen. On the island during my revisit the changes in technology and in the terrain necessitated some bending, and generated some kinds of diffraction. In Copenhagen the public space and all my co-performers provided other challenges — and diffractions.

Here, in this video essay the negotiation takes place with time and duration, how much can be included and made visible at the same time, and perhaps also with other approaches to doing things with performance. Why look at this now? Is there a point in doing less? And what happens when this “less” is multiplied, layered and diffracted? Does it do something to our usual understanding of self-representations and self-reflective activities? Does it make any difference if I call it self-diffraction? And there is the question we began with: What is the pedagogic, political or therapeutic potential in such “self-diffractive” rather than self-reflective exercises?

One obvious use is to assist us in moving beyond the idea of self as a given or fixed entity and realize the multiplicity and relationality involved in all forms of self-imaging or performances of the self. That said, self-diffraction could also be interpreted as simply multiplying variations or images of the self, as a celebration and excess of selfie-fantasies. The ultimate aim and tool of the current selfie-culture?

Self-diffraction or not – choosing a place (or perhaps simply a pose) and returning to it regularly, with or without a recording device, can serve as an example of an affirmative practice, one which is available to artists and non-artists alike.[15] Sitting, standing, posing or some other kind of simple action repeated in a particular place, requires no special skills. This kind of repetition provides an opportunity to rest and reflect, to enjoy the living environment; and if documented, the practice can produce a record of the constant transformations taking place. Such traces can be used as artworks, like the video works shown here, but also as a form of journaling. Choosing a place in a more or less living environment, and choosing an action that emphasises the sensual experience of that environment increases the joyful, healing and affirmative qualities of the practice. Perhaps something of those qualities can be experienced through documentation as well. The effect of the video works on the viewer, however, and the effect of the actual practice on the performer of the action should not be conflated. In this context it is interesting to focus on the actual practice, since that could be developed into a method to be used by others for pedagogical purposes.

We could ask whether such practices could have a therapeutic function? The idea of repetition is perhaps more easily associated with obsessive actions, negotiating repressed or traumatic experiences impossible to articulate or experience directly. But repetition with a difference can be a powerful tool, as feminist theoreticians have argued again and again. By way of repetition, we learn new ways of acting and experiencing. By repeating something that gives us pleasure, joy or peace, we incorporate those experiences into our lives and turn them into habits. Finding a place to visit, or a pose to “diffract” and performing a private ritual as an interruption in one’s daily life can function as an affirmation of one’s connection to the living environment, as an action to restore balance, invigorate and energize, or an aid in imagining alternatives, and thus, as a therapeutic practice on a small scale.

Perhaps such activities could be used as pedagogical tools as well, even as a form of performance pedagogy? But teaching what? Not performance skills or communication skills or collaborative skills, not even endurance or willpower, but rather the skill of creating alternative habits or new versions of the self and thus empowering us to develop our lives, at least on some level. Whether this kind of softly affirmative practice could give us a new horizon or something even hinting at “a new world, a new body, a people to come,” as Elisabeth Grosz suggested, is perhaps to ask for too much. Or, perhaps it is not. Perhaps we should believe the streetwise girls, who say: you get what you ask for.

[1] One inspiration for inserting variations of older videos into a contemporary one was an artwork by Vincent Roumagnac, “We Split We Split,” which I saw in Helsinki in 2016.

[2] Research Day III: Performance Pedagogy, 16 November 2018, University of the Arts Helsinki Theatre Academy https://uniarts.fi/tapahtumat/01022018-0958/research-day-iii-performance-pedagogy

[3] The video compilation was published as “How to do things with repetition?” video with text, Icehole #6, 2017, The Live Art Journal.http://icehole.fi/vol-6_issue2_2017/video-by-annette-arlander/ Other, more academic, published compilations include a return to the site of the year of the goat in “The Shore Revisited.” Journal of Embodied Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018, (30-34) https://doi.org/10.16995/jer.8 and “Return to the Site of the Year of the Rooster.” How to do things with performance, Edited by Annette Arlander, Hanna Järvinen, Tero Nauha and Pilvi Porkola, Ruukku — Studies in Artistic Research, no. 11, 2019. http://ruukku-journal.fi/en/issues/11

[4] Year of the Rat — Mermaid 1-2 http://av-arkki.fi/en/works/year-of-the-rat-mermaid-1-2/

[5] Day and Night of the Rat — Mermaid https://av-arkki.fi/works/day-and-night-of-the-rat-mermaid/

[6] Andersen, H.C. “The Little Mermaid.” Hans Christian Andersen: Fairy Tales and Stories, Translated by H. P. Paull, 1872 (orig. 1836), http://hca.gilead.org.il/li_merma.html

[7] “Santa Marian suola-altaat — epäpaikoista ja performatiivisen tutkimuksen haasteista” [The Salt Basins at Santa Maria — Non-places and the Challenges of Performative Research], Näyttämöltä tutkimukseksi — esittävien taiteiden metodologiset haasteet [From Stage to Research — Methodological Challenges of Performing Arts], Edited by Liisa Ikonen, Hanna Järvinen, Maiju Loukola, Näyttämö ja tutkimus 4, Teatterintutkimuksen seura Helsinki, 2012, pp. 9-26. http://teats.fi/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TeaTS4.pdf

[8] “Performing Non-place and the Challenge of Performative Research” Performing Landscape — Notes on Site-specific Work and Artistic Research (Texts 2001-2011), Acta Scenica 28, Theatre Academy Helsinki, 2012, pp. 377-395. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/37613

[9] This is something I have focused on in more recent works, especially in the project “Performing with Plants” https://researchcatalogue.net/view/316550/316551

[10] It is of course ironic to call oneself an auto-didact, if one has been studying for a large part of one’s life I spent 22 years as a student at Helsinki University, for instance, besides engaging in doctoral studies for seven years at the University of the Arts Helsinki, but my basic education was that of a theatre director and theatre scholar, as a performance artist and visual artist I am completely self-taught.

[11] Such as Drip Music https://moma.org/collection/works/127311

[12] The process is described in detail in Arlander 2012, pp. 371-376.

[13] Year of the Rat — Dripping http://av-arkki.fi/en/works/year-of-the-rat-dripping-short/ There is a longer version (68 min. 47 sec.); an installation version includes “Year of the Rat — Dripping & Jar” (2 x 6 min. 47 sec.)

[14] PSi #14 conference Interregnum at the University of Copenhagen, 20-24 August 2008. When I wrote about the work for the first time, the sculpture had temporarily been transported to Shanghai for Expo 2010, with a live streaming from there on a screen at the original site.

[15] These thoughts are a further development of my discussion in “Performing Landscape as Affirmative Practice” (Arlander 2012, 368-376).

Andersen, H.C. “The Little Mermaid.” Hans Christian Andersen: Fairy Tales and Stories. Translated by H. P. Paull, 1872 [orig. 1836]. http://hca.gilead.org.il/li_merma.html. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Arlander, Annette. “Return to the Site of the Year of the Rooster.” Ruukku — Studies in Artistic Research, no. 11, 2019. http://ruukku-journal.fi/en/issues/11. Accessed 19 June 2020.

———. “The Shore Revisited.” Journal of Embodied Research, vol. 1, no. 1, 2018, pp. 30-34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/jer.8

———. “Dune Dream — Self-imaging, Trans-corporeality and the Environment.” Body Space & Technology, vol. 17, no. 1, 2018, pp.3-21. DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/bst.293

———. “How to do things with repetition?” Icehole #6, 2017. http://icehole.fi/vol-6_issue2_2017/video-by-annette-arlander/ Accessed 19 June 2020.

———. Performing Landscape — Notes on Site-specific Work and Artistic Research (Texts 2001-2011), Acta Scenica 28, Theatre Academy Helsinki, 2012. https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/37613. Accessed 19 June 2020.

———. “Santa Marian suola-altaat — epäpaikoista ja performatiivisen tutkimuksen haasteista” [The Salt Basins at Santa Maria — Non-places and the Challenges of Performative Research]. Näyttämöltä tutkimukseksi — esittävien taiteiden metodologiset haasteet [From Stage to Research — Methodological Challenges of Performing Arts], Teatterintutkimuksen seura Helsinki [Theatre Research Society Helsinki], Edited by Liisa Ikonen, Hanna Järvinen, Maiju Loukola. Näyttämö ja tutkimus 4, Teatterintutkimuksen seura Helsinki, 2012, 9-26. http://teats.fi/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/TeaTS4.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Augé, Marc. Non-places, Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London, New York: Verso, 1995.

Barad, Karen. Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart, Parallax, vol. 20, no. 3, 2014, pp. 168-187.

———. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2007.

———. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs, vol. 28, 2003, pp. 801-831.

Bolt, Barbara. “A Performative Paradigm for the Creative Arts?” Working Papers in Art and Design, vol. 5, 2008. https://herts.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0015/12417/WPIAAD_vol5_bolt.pdf. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Braidotti, Rosi. “Affirming the affirmative: On Nomadic Affectivity.” Rhizomes, Issue 11/1, Fall 2005/ Spring 2006. http://rhizomes.net/issue11/braidotti.html. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Garoian, Charles R. Performing Pedagogy. Toward an Art of Politics. New York: SUNY Press, 1999.

Geerts, Evelein, and Iris van der Tuin. “Diffraction and Reading Diffractively.” New Materialism. How Matter Comes to Matter, 2016. http://newmaterialism.eu/almanac/d/diffraction. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Jones, Amelia. Self / Image — Technology, Representation and the Contemporary Subject. London and New York: Routledge, 2006.

Kontturi, Katve-Kaisa, and Milla Tiainen. “Feminism, Art, Deleuze and Darwin: An Interview with Elizabeth Grosz.” NORA — Nordic Journal of Women’s Studies, vol. 15, no.4., 2007, pp. 246-256. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08038740701646739?scroll=top&needAccess=true&journalCode=swom20. Accessed 20 June 2020.

Nauha, Tero. “Performance Art Can’t be Taught.” Performance Artist’s Work Book. On Teaching and Learning Performance Art – Essays and Exercises, Edited by Pilvi Porkola. University of the Arts Helsinki, Theatre Academy and New Performance Turku, 2017, pp. 61-70.

Pritchard, Helen, and Jane Prophet. “Diffractive Art Practices: Computation and the Messy Entanglements between Mainstream Contemporary Art, and New Media Art.” Artnodes, Issue 15, 2015. https://artnodes.uoc.edu/articles/abstract/10.7238/a.v0i15.2594/. Accessed 19 June 2020.

Sauzet, Sofie. “Thinking Through Picturing.” Teaching With Feminist Materialism, Edited by Peta Hinton and Pat Treusch. Utrecht: ATGENDER, 2015, pp. 39-53.

Spatz, Ben. “What Do We Document? Dense Video and the Epistemology of Practice.” Documenting Performance — The Context and Processes of Digital Curation and Archiving, Edited by Toni Sant. London: Bloomsbury, 2017, pp. 241-151.

The works included in the video essay as well as other performances for camera recorded during the same year (all DV, 4:3, 2009, if not otherwise indicated), listed in the AV-archive:

Year of the Rat — Mermaid 1-2, (2-channel installation 34 min. 33 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/year-of-the-rat-mermaid-1-2/

Year of the Rat — Uphill — Downhill (2-channel installation 19 min.12 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/year-of-the-rat-uphill-downhill/

Year of the Rat — Dripping (short) (6 min. 47 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/year-of-the-rat-dripping-short/

Day and Night of the Rat — Mermaid (11min. 10 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/day-and-night-of-the-rat-mermaid/

Mermaid Variations 1-9, (3-channel installation 3 min 58 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/mermaid-variations-1-9/

The Little Mermaid — 95th Birthday (5 min.10 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/the-little-mermaid-95th-birthday/

On the Atlantic Shore 1-2 (2-channel installation 23 min.17 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/on-the-atlantic-shore-1-2/

On the Mediterranean Shore 1-4 (2-channel installation 10 min.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/on-the-mediterranean-shore-1-4/

Sal 1-2 2010, HDV 16:9. (26 min. 17 sec.)

https://av-arkki.fi/works/sal-1-2/