University of Massachusetts, Amherst

University of Washington

Photo Assistants: Abe Yuta, Joy Jarme, and Tillie Sakamoto

Mu (nothingness).

Not knowing (from Zen practice).

The funk (Free your ass… and your mind will follow).[1]

MuNK (my dancer name).[2]

Commentary

Before you begin, she is there.

Not-there, in your body. Not-there, in the images.

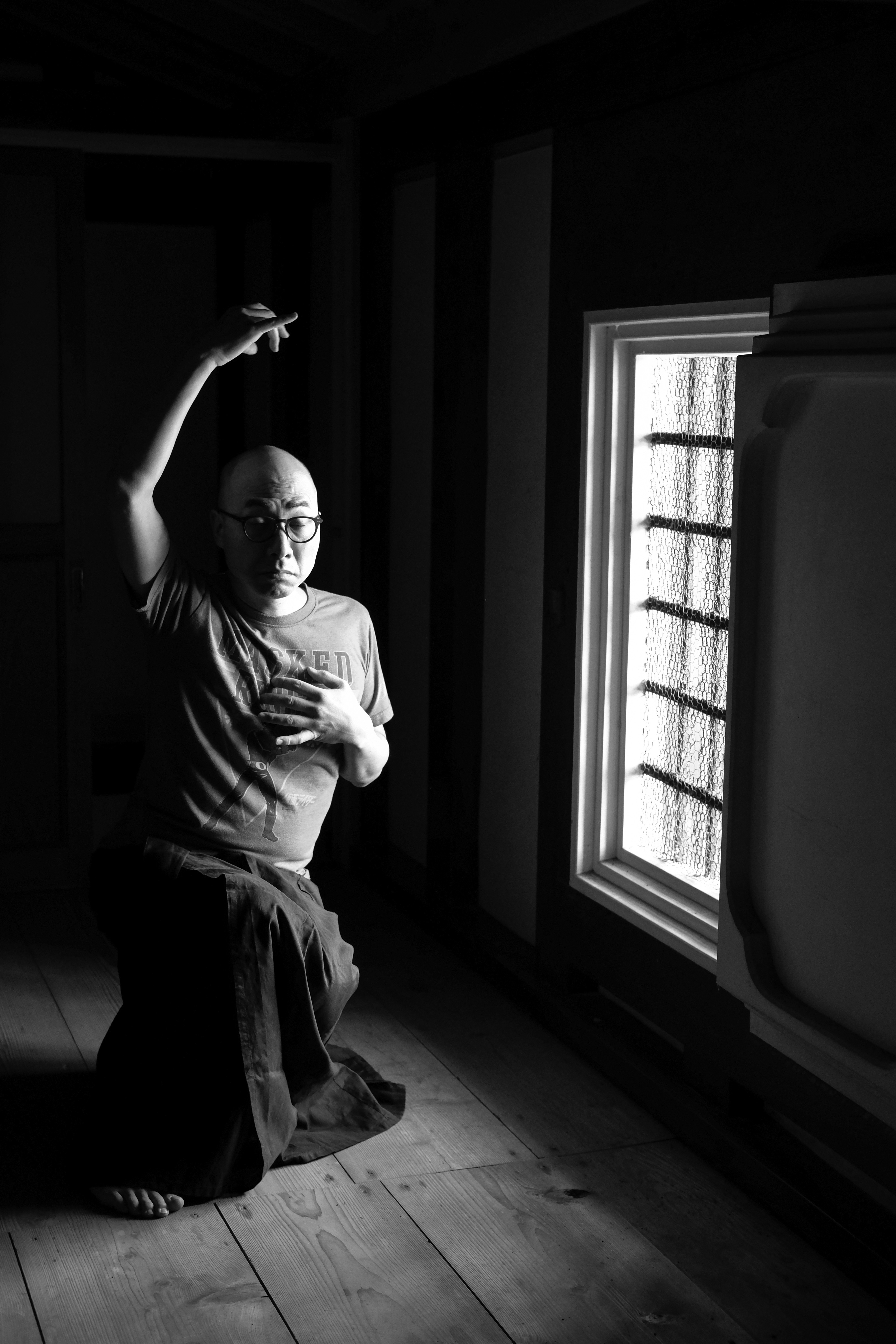

What I understand of your butoh, to begin: these photographs are not photographs of her.

Butoh is in a perennial state of becoming. Butoh performers want what we don’t have, what we are not and may never be. And yet the vain attempt is the thing itself that we desire. In our desperate, definitively irresolute gestures, between body and image, we find what we are looking for. We are our shadow as much as our flesh. At the same time, we hide our essence from the light, showing just enough for a sharp impression, but no absolute truth. We leave mutable traces of our path, like a deaf, mute, and blind person in a dark chamber, groping their way through the ankoku (utter blackness), until the moment an opening occurs, letting in the light, like a camera shutter, just for an instant.

Perhaps this is why butoh and photography have existed in a symbiotic relationship from the beginning. In the year after photographer Hosoe Eikoh witnessed Kinjiki, the first butoh performance by the movement’s founder, Hijikata Tatsumi, in May 1959, he engaged Hijikata and his dancers in a series of photo and film shoots. Hosoe was a rising star in the Tokyo avant garde, and the timing was ideal for the two men to help realize each other’s visions. The butoh body was framed by the camera from its inception. It was the project of many post World War Two Japanese photographers to visualize the inexpressible identity crisis of tension and liminality between pre war Japanese ness and post war Western ideology, and Hijikata aimed to corporealize this feeling:

But, first of all I must, I think, wipe out all art and culture. This “dance experience,”[3] which fiercely took up this challenge for the sake of cultural material, has been for me a marvelous spiritual journey. There is, I always feel, an unfathomable ocean before my body. (Hijikata 41)

Characteristics common among many postwar Japanese artists were a search for identity within widespread social ambiguity, radical subjectivity as a response to these chaotic feelings, and a concomitant focus on the carnal body (nikutai), especially individual corporeality in place of the traditional, nationalist, Emperor centric, body politic (kokutai) (Sakamoto 26 28). Similarly, as Jonathan W. Marshall explains, both butoh artists and post war Japanese photographers were focused on issues of visibility/invisibility, the subconscious, and “corporeal part objects,” thus driving them to a reciprocal exchange of ideas and collaborations (Marshall 158 159).

I believe the effect of this symbiotic relationship on Hijikata’s core aesthetic is palpable. His sense of ankoku, even decades and multiple transnational generations of artists after his death, makes butoh performance for me like a series of still images, roll of film, or photo album. Hijikata’s butoh body is always spectral in that it is intended to garner agency via performing its brokenness, that which by normative definition cannot hold agency; a broken version of a postwar, reconstructed holism vacated of its ability to define itself as-is or beyond whatever parameters it’s allowed by late capitalism. Similar to the main character in Abe Kobo’s novel, The Face of Another (1964) or Teshigahara Hiroshi’s eponymous film (1966), I see Hijikata in the 1960s like a Japanese salaryman able to comfortably function and “perform himself” in everyday life only after choosing a complete facial reconstruction.

As for my body imagery and photo imagery, I may not be focused on the same parts, per se, but as a practitioner labeled as:

artist (subjective) and scholar (objective)

dancer (actor) and photographer (observer)

Japanese (Eastern) and American (Western)

I too am searching for an ambivalent evocation of my in between ness, ricocheting between the knowing self and the untamed other.

In-between what and what? Between the place where they ask, where are you from?, and the place you go looking for because it’s the place that they think they mean when they ask you, but where are you really from?

How does it feel to be a problem — the kind of problem whose home is among those who ask where you are from, and whose dream of a homeland passes through their fantasy of the place where they would send you back?

“Japanese American” is not in-between; that’s why, like “Asian American,” you aren’t supposed to put a hyphen in it. [4] “Japanese American” is not a dual identity crisis. Before the war, [5] the immigrant Issei, the first generation, had this idea that their second-generation children, the Nisei, would be a bridge — between East and West, Japan and the U.S., empire and empire. It turned out that the bridge [6] didn’t connect on either side.

Japanese American is the performative negation of a double negative. [7] No and no.[8] The non-alien. [9]

When I say “Japanese American” — I am (a) Japanese American, you are (a) Japanese American, we are (two) Japanese Americans — I gesture to the impossibility of living in (or out) the double negative, no no, as if I could conjure an affirmative identity out of the denial of history, two times over. It is supposedly very “American” to conjure an affirmative identity out of the denial of history, but that’s not supposed to mean us, you and I, because the double denial of history that gives us a name is too specific.

One might even feel “Japanese American” in the collective affirmation of the impossibility of living in (or out) this denial. But all that I can ever seem to conjure in this gesture is the spectrality of the non alien, who is so resolutely not-there [10] every time I deny her name.

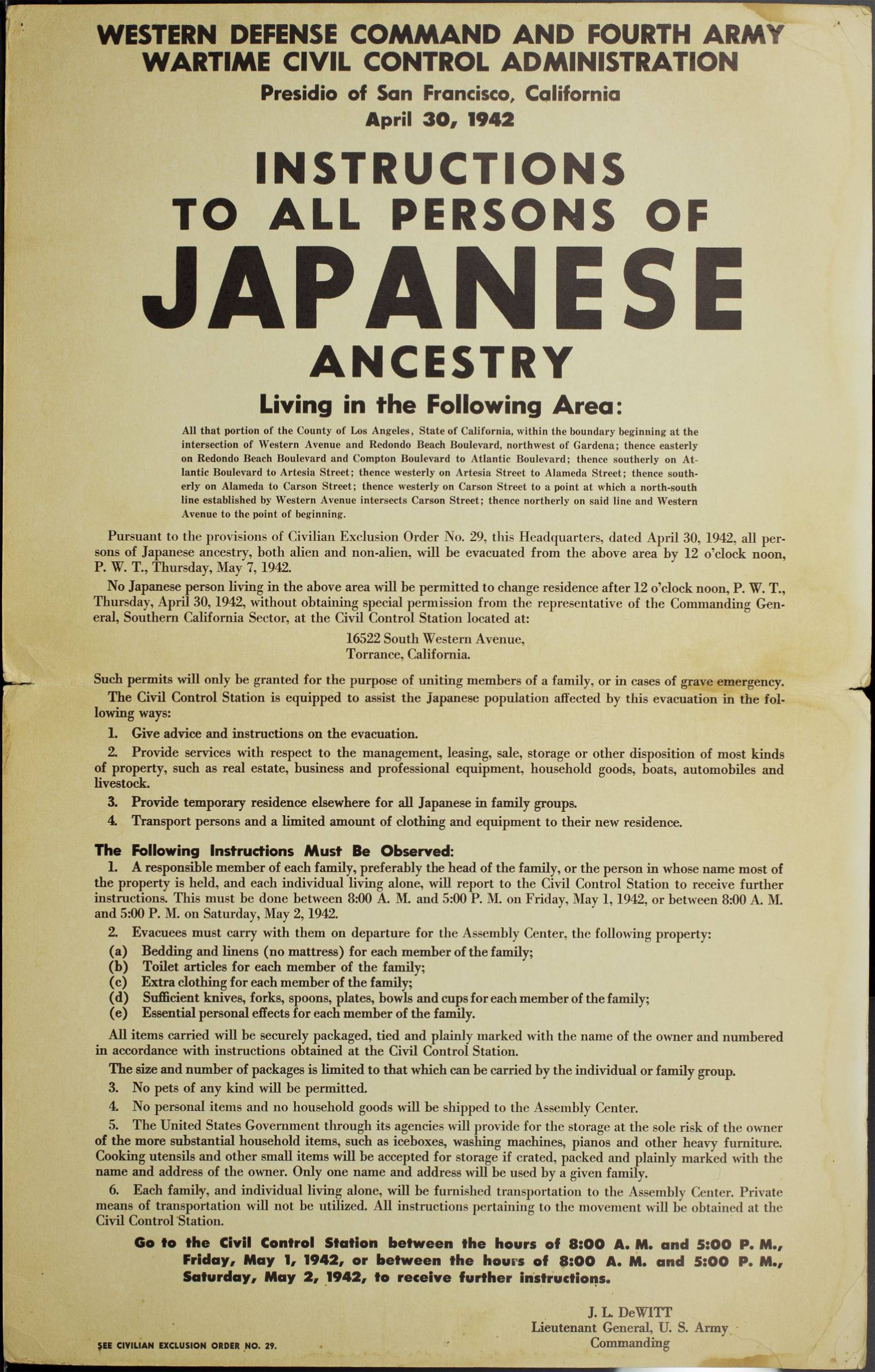

As seen in the iconic posters that appeared up and down the West Coast in 1942, the “non-alien” was the term by which the U.S. government formally demanded the presence of natural born citizens of Japanese ancestry. In this name, they were subjected to forced removal, first to temporary detention centers, and thence to concentration camps. In legal terms, the non-alien represents a paradox, because she is clearly a variety of what she is not — a non alien, in actuality, is unmistakably a type of alien.

Properly speaking, the non alien is a citizen whose rights may be cancelled on racial grounds.

The instability that the non-alien embodies proved more than the law or the nation could bear, all the more so when it became clear that the U.S. would likely win the war, and that racialized mass incarceration would become an embarrassment to its postwar geopolitical interests. The process of rehabilitating Japanese Americans, as a loyal minority whose faithful endurance of racism testified to the benevolence and perfectability of U.S. power, began in the camps themselves, and has continued unabated down the decades. The non-alien is what the Japanese American is not — the denied figure who would expose Japanese Americans’ supposed freedom as relative privilege and terrorizing vulnerability, the double negation that constitutes Japanese American identity.

She is, in the most mundane and tangible sense, a ghost. I am already so familiar with her absence, which is her general condition, that I can find it in your photographs right away. The non-alien is always not there. And even ghosts have a history.

The Wright Brothers spat airplanes into the technological meme pool; the idea then spread like a virus in a chicken coop.

— Lawrence Lessig (3)

The reaction could even be called panic. The rough grain, the extremes of black and white, the radical lack of focus; none of this was normally seen in photographs.

— Nakahira Takuma on photographer William Klein’s book, Life is Good & Good for You in New York: Trance Witness Revels (Takuma 362)

Ideas touch us. Dancers touch each other. Mobile devices, the prime means of social media interaction, are haptic technologies designed for touch triggers and sensory emotive reactions into and out of virtuality. Photos posted on social media reach out for mind and body. Photos circulated within a community of like-minded individuals function likewise.

Along with the physical devastation wrought by the firestorms and mushroom clouds brought by the Americans, hearts and minds were torn asunder, as well. No wonder that the Occupation Authority made a first priority of reforming, and then marketing, revised Japanese values — economic, political, and domestic. The natives were allowed to do things their own way, as long as it still felt like Main Street circa 1952, the year the Occupation nominally ended and Eisenhower was elected President.[11] Disillusioned by such policies and the larger Cold War, but also the preceding decades of domestic militarism, postwar Japanese photographers became strongly influenced by their American contemporaries, especially William Klein and Robert Frank, in whose images lay an innovative freedom from both classical composition and photojournalism’s tradition of idealistic humanism. These Japanese artists didn’t so much reject Western ness outright as delve into the ambivalences caused by its transplanting into their own domestic setting. From the muted threats of Tomatsu Shomei’s privileged GIs to Fukase Masahisa’s desperate erotics and Moriyama Daido’s transitory solitudes, there’s a palpable desire for connection in the midst of a violent, emasculating chaos: cultural colonialism masquerading as socio-economic recovery (Tomatsu; Fukase; and Moriyama).

Hijikata and Hosoe stared hard into the same psychic landscapes. The first decade (1959-1968) of their performative, photographic, and filmic collaborations pictured alternately confused, contradictory, and desiring bodies, seeing and masked, entangled and ordered. These are bodies torn from their roots, with only each other’s shadows for solace and communion. In the freshly postcolonial void of 1960s Japan and especially in the autobiographical performance photo essay, Kamaitachi (1969), Hosoe and Hijikata reconstituted collective identity in the lost and found of their subjectivity.

I see Hosoe and Hijikata spitting images into the gene pool of butoh futures via obsession with a mythology and nihonjiron (Japanese-ness) inspired by their families’ backwater home region of Tohoku.[12] Seeing Hijikata’s ruralist, Tohoku-styled dancers in the 1970s, I see that he wants us to believe this world of his childhood, to feel the abyss of decades, even centuries, between business suits and Lucky Strikes on one side, and rice paddy mud and freezing winds against our skin on the other. I see that he wants us to believe ourselves. I think, therefore, of my own 1970s L.A. youth, my mind’s eye drawn inexorably sideways into blackness by Jim Kelly’s Blasian-style swagger,[13] Cheryl Song’s Soul Train sway,[14] and KJLH, KGFJ, and KDAY being the soundtrack of the Lakers-lovin’ playground hoops that I frequented citywide.[15]

In other words, when I see butoh, I see black. When I think of Hijikata and Hosoe devising a new strategy of being themselves via body and image, I sense something akin to Stefano Harney and Fred Moten’s description of black culture’s necessary reconstitution of love rooted in the hapticality of the hold during the Middle Passage: “To feel others is unmediated, immediately social, amongst us, our thing, and even when we recompose religion, it comes from us, and even when we recompose race, we do it as race men and women” (Hijikata 105).

When I see butoh / I see black: perception, as the history of photography shows, is both technologically mediated and racially embodied, in the training and counter-training of the senses that may be called aesthetics. What you see, you see as a Japanese American, doubly alienated from cultural practices marked as Japanese and African American. You see, in other words, via an inauthenticity that is your own (and mine), haunted by what watches from behind your lens and behind your eyes.

That is, butoh and black converge within a form of perception conditioned by what cannot be directly seen or sensed — the non-alien whose absence draws these several elements into a (re)composition.

A thesis: to be (a) Japanese American, as, in the everyday sense, [16] you and I are, is to be severed from a history that defines you, via neither repression nor shame, but a structurally imposed forgetting. On the other side — “beyond death” is really the simplest way to put it — is an agency, a form of life that continues to operate through you, even as it remains inaccessible to you. This agency is what I am calling the non-alien. [17]

It is this severing that introduces a kind of inauthenticity into your relationship with whatever one calls Japanese culture, for this severing is constitutive of the syncopated racial histories of postwar Japan and Japanese America, as each was remade by the imperatives of ascendant U.S. global power. Your relationship with whatever one calls African American, Latinx, or American culture is rendered inauthentic by this same severing, even when specific cultural practices associated with those identities are traceable to a historical milieu already shaped by Japanese Americans.

If you could restore what was cut away and remember what it is structurally impossible for you not to forget, your possession by the non-alien would be complete: you would cease to be Japanese American, and become something else. For now, you can only trace the shape of her absence, to call into that void and await what might emanate from it.

It’s a little bit complicated. It is a matter of photography. It is a matter of just a boy. How do you record your memories? Is it possible for photography to record memories? But the photographer wants to do that.

- Hosoe Eikoh on Kamaitachi (2010)

My visual-corporeal vernacular, inherited from Hosoe and Hijikata’s groundbreaking innovations, is hybrid, multiple, and indeterminate. W.J.T. Mitchell, in speaking of the prevalence in every community of “vernacular visuality,” or “the ordinary language of communication and reflection, the medium we hold in common” (Mitchell 12), argues for every individual as a bearer of vernacular culture:

Every human being is the center of a world, a cosmos of experiences and intuitions, a universe in which he or she finds a place — or finds oneself lost, adrift, perhaps even displaced. Every human being, even the blind, inhabits a world of visuality populated by images. Their native language for discussing that world is shared and shareable to some extent. (12)

Hijikata received such shared images from his modern dance colleagues in postwar Japan, and especially from dancer (and eventual butoh co-founder) Ohno Kazuo upon seeing the latter dance in 1948: “For years this drug dance stayed in my memory. That dance has now been transformed into a deadly poison, and one spoonful of it contains all that is needed to paralyze me” (36).

I feel like Hosoe and Hijikata shared their Kamaitachi images with me as well, redolent with their reimagined childhoods. Their images are my poison. Their childhood, however, is not mine. I have to create my own Kamaitachi, one that revisits influences on my life, in geographical space and time, as well as the corners of my mind. A collection comprehensible as an amalgam of self and other via the appropriate sharing metaphor of this current time period, i.e. a social network.

But how to do this? Like butoh’s visual-corporeal presence, our identity in social media is inherently spectral, a haunted narrative competing with its virtual and corporeal selves. Definitions of social network as a term, for example, often list two likewise interpretations: one technology-based and the other interpersonal.[18] The seeming divide approximates somewhere along the lines of the corporeal and unfiltered versus the virtual and industrially mediated. Person versus representation. Body versus image.

Is there a way, however, to consider the corporeal and virtual as one and the same? I believe the nature of productive and desired information communicated and shared within social networks — the stuff of our everyday lives — is a process that exists and starts in our imagination as much as our bodies. As Dock Currie writes, “The app is in here, in the blood, in the head…” (Currie 85).

Moreover, the most popular social media apps are either photo-based (Instagram and Snapchat) or overwhelmed with visual content (Facebook and Twitter), demonstrating that photography - writing with light is no more outmoded in the digital age than telecommunications or transportation. Just as the latter give us the ability to speak and move across distances, so the former enables us to see across myriad borders and divides — physical, social, cultural, and spiritual. Photos allow us into a place and moment to gaze and examine, to witness and bear witness. Depending on the context, photos may also endow us with the active ability to illuminate, narrate, or provoke. In these combined senses, photography is both perception and projection. As much as photographers write with light through the final images they craft and output, their eyes are also inscribed upon by the light they allow into their lens.

The amalgam of photo-based images we gather and display on social media is thus an integration of the world we see, or at least a version/vision of it that we imagine, and the one that wants to be seen. The social network is a mode for experiencing how we see who we are, one constructed of moments out of our constantly evolving past, one that is inherently both personal and shared.

Thus, my non-alien wants the impossible: to be seen.

How we see / who we are: perception and identity, as always, necessarily linked. Who we are invokes identity as a social relation. The algorithmic uncanny, that alienating sensation of an intelligence that “knows us better than we know ourselves,” should remind you that identity only finds form in differentiation, in how one’s body and the virtuality of its traces are distinguished from others. Identity is necessarily a mystery to one’s self, whose truth lies elsewhere — not in another body, or even in a machine, but between socially produced code and the information it processes.

How we see is one manifestation of a historical regime of perception that manages the determination and sorting of social identities, the recalibrations of power that stabilize a dynamic hierarchy, and that materializes in technologies of representation and communication, which become a terrain of struggle. In social media, photography, and viral video, both the justification of an existing order and the revelation of its truth are continually being produced.

To speak of a mode for knowing / how we see / who we are is to emphasize epistemology and critique, which both justify and expose a regime of perception, and the order it serves. Alternately, one might stress aesthetics, as a set of enabling constraints on the perceptions of the senses, and fugitivity, the capacity to elude justification’s clutches — to live outside, or outside within, the dominion of an order of justice.

In the place you and I are from and live, historical regimes of perception are constituted and managed through technologically mediated rituals of racial and sexual violence. Under imperialism, the social order is constituted by pervasive forms of violence that must be perceived by its subjects as justice — as the work of expanding and securing justice’s domain. One’s position in this social order determines the kinds of violence one does or does not perceive. [19]

When this order is in crisis — when an empire rapidly expands, contracts, collapses, or is swallowed whole by another — a regime of social perception begins to break down, exposing its structuring violence as a latticework of fractures. Such a crisis became evident after the murders of Trayvon Martin, Renisha McBride, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Laquan McDonald, Tamir Rice, Sandra Bland, Samuel DuBose, Philando Castile, and so many others. [20] The socially mediated circulation of accounts and viral videos of these killings manifested the crisis of a regime of perception, for there was nothing new about this violence except the way it suddenly came into focus.

This was a matter not merely of sight or sound, but of kinesthetic perception. The tensing of your muscles and the feeling in your stomach when you watch, once more, a person being killed; the mental process of imagining all the possible arrangements of one’s arms that could be described, credibly, as “reaching for his waistband” — in these instances, social media, photography and viral video instruct and deconstruct the ways identity is perceived from one body to another.

Under current conditions, the algorithm further complicates the exposure and reconstitution of a regime of perception corresponding to a ruling consensus. There is no resolution to the crisis manifested in #BlackLivesMatter — the rapid and chaotic decline of US global power, and of its diversity-talk, its governing language of rule-across-difference in the post-Soviet era. Yet these killings no longer go viral, because the algorithm has already sorted users according to the ways they have determined what to perceive and not perceive.

And the algorithm further allows politics to proceed by privileging coercion over consent, recalibrating the pursuit of hegemony, or abandoning for a justice predicated on sheer domination. In its wounded, aggressive reassertion of a gendered and racialized prerogative of violence, the current order reveals its profound vulnerability and dangerous volatility.

December 24, 2016. I ride three trains from Tokyo to Akita Prefecture in the Tohoku region of northern Japan and arrive late afternoon to Tashiro village in the precinct of Ugo Machi. It’s freezing outside, and there’s two feet of snow everywhere, but the sun is setting fast, so I drop my bags quickly at the inn and set out with camera and tripod. I have two days to jump-start an international photo project inspired by Kamaitachi, much of which was shot in and around Tashiro and the rest in Tokyo between 1965 and 1968.

I wind my way down the deserted main street, past a noodle shop, a sundries store, and the elementary school where Abe Yuta, the ryokan manager, sends his three daughters. Abe grew up in Tashiro when there were four schools. Like countless rural townships in Japan, however, it has taken only two decades, one generation, for Tashiro’s population to plummet to a fraction of its former size. Yuta, his wife, and their children are the only young family remaining.

As I eye possible shooting locations, images and thoughts rush through my head…

Hosoe telling me that Marc Chagall’s paintings are personal in the same way as his photos, that they are Chagall’s Kamaitachi (Hosoe).

My nisei maternal grandmother as a teenager in Shizuoka Prefecture, standing in her family’s homeland, staring across the Pacific at her own homeland, where she will always live as a foreigner.

My nisei paternal grandfather, born and raised on Maui in the Hawaiian islands, staring out to sea in both directions.

Now I’m here in Tashiro, in Hijikata’s father’s home region, staring out to the expanse of small houses and rice fields covered in snow, pondering how butoh has found a “home” in the body of a yonsei nikkei (fourth generation Japanese abroad)…

But what could it mean to find a home in a body for which inauthenticity is a general condition? Before the war, a Nisei’s restless gaze might roam across the water, in all directions. But your eyes are closed.

In his photo, Hijikata’s face tilts downward, his mouth set, as if reflecting on some past action, and its consequences. But yours seems to be concentrated on a dream — as if, in some future moment of convergence, the severed paths of history might be rejoined, and your will could be released to the agency of the dreaming.

For a Yonsei to “return” to Japan is to seek a passage through inauthenticity, because inauthenticity is in the nature of what you and I are. As Asian Americans, you and I are deemed perpetual foreigners, disallowed any claim on “culture” in the places to which you and I belong, by residency, upbringing, or ancestry. As Nikkei, and grandchildren of camp, you and I are severed from the intergenerational memory of a Japan that is historically discontinuous with the Orientalist visions of the U.S. imagination, and from the contemporary nation that reconstructed its past after the loss of its empire.

Not long ago, idly typing my family’s name into an online archive, I discovered a collection of photographs of my great aunt, Yoshiko Tajiri, from her days as a U.S. Army journalist in Occupied Japan. They were taken by her friend, Shiuko Sakai, a talented photographer, who donated her collection to the archive many decades later. No one in my family had ever seen them.

In the photos, like this one from a trip to Sendai, my great aunt is stylish and magnetic, projecting a glamour and easy confidence that feels characteristically American, profoundly Nisei, and very California. She is always smiling, the focus of the action, and everyone else always seems to want to touch her.

She is also the representative of a conquering army. In this landscape, her gaze and that of the Japanese women she encounters pass each other by, in silence.

Members of that same army had escorted her, her widowed mother, and three of her brothers to a makeshift detention center at the Santa Anita racetrack, where they slept in a horse’s stall, and then to a permanent concentration camp at Poston, on the Colorado River Indian Reservation. (My grandfather was elsewhere at the time, wearing the same uniform as his family’s jailers, drafted before the war began.)

Since this time, Japanese and Japanese Americans have been outside relations, so to speak. Even the secrets that we need to tell each other and cannot are, in their way, unacknowledged cousins. In the coming decades, Japanese Americans would be celebrated as America’s model minority, while the Japanese nation served a similar function for U.S. power abroad. The price paid, in both cases, was imposed as a domain of forgetting, a netherworld lying like a chill on top of the reality one shares with everyone else.

No wonder that such a situation would enchant photographers, or even conjure them, in search of the image that might finally harmonize seeing and sight, touching and touch — or reject that impossible desire, to pursue some other orchestration of what Moten calls the ensemble of the senses.

For Nisei photographers after camp, and for Japanese photographers after occupation, image-making offered a way of negotiating a crisis of social perception — questions of visuality and kinesthetics, of embodiment and stylization. Here on the other side of the American Century, amid the foundering of U.S. empire, as a similar aesthetic crisis rolls across all your mediated social networks, your hope should not be to stabilize perception, to fix what you see and feel and know. Linger instead in instability, listening for what emanates through the cracks, what Moten calls a terribly beautiful music. Better to let the images dance before your eyes.

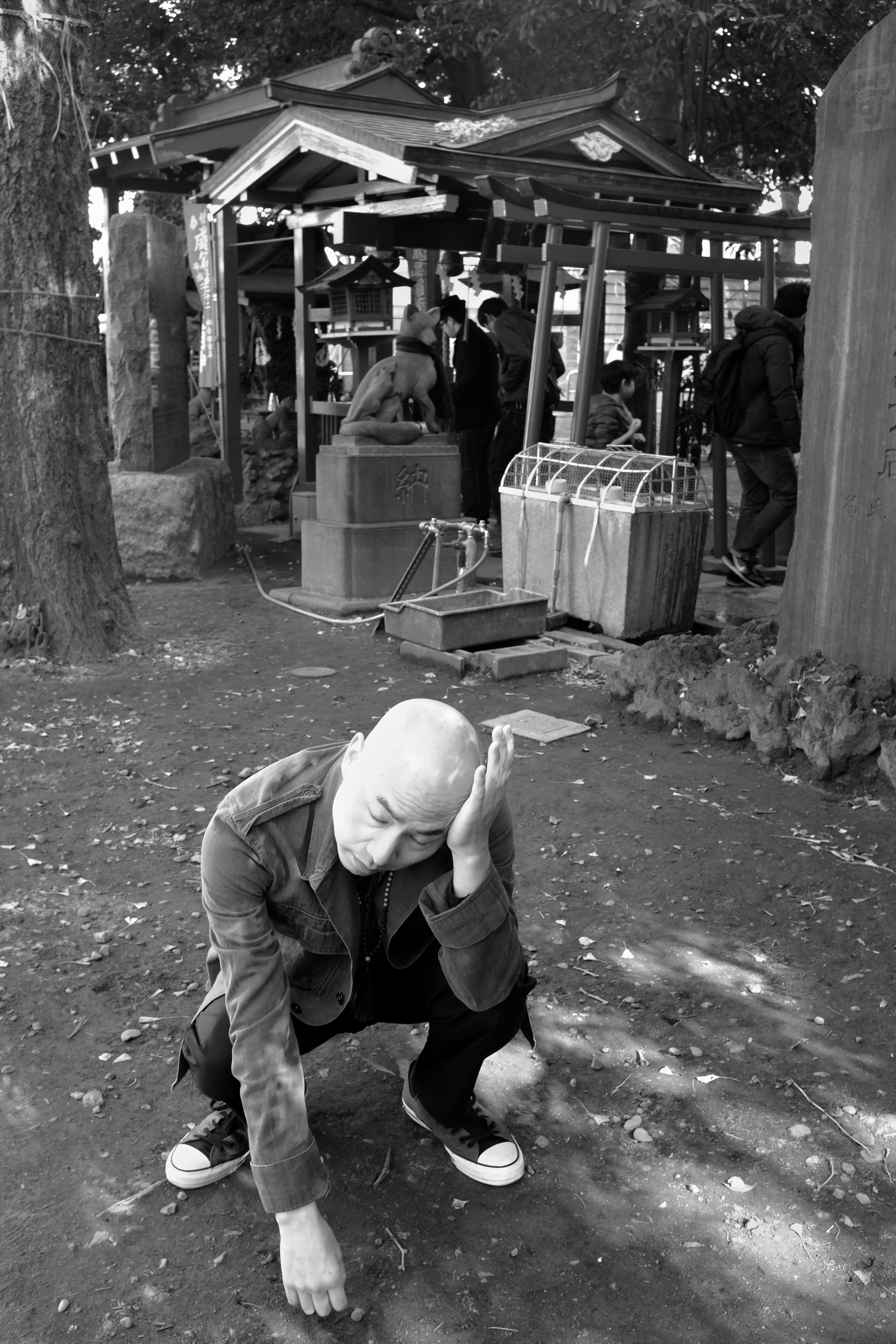

Yuta generously offers to drive me around to various sites in Tashiro where Hosoe and Hijikata took photos. I meet numerous villagers who vaguely recall the history of the project and those who (inadvertently) participated on camera.

The most precious of my encounters is Shibata-san, who appears in a Kamaitachi photo in the background next to her house as Hijikata monkeys around on a straw mat for a group of children. We drive up to her house, and Yuta explains the project to her. I ask if she would be willing to be in my version of the photo, to help me recreate and reimagine the image. A bit shy, Shibata-san nevertheless agrees. She stands in the background in the same place as before, on the path to her tool shed, while I squat with a camera in hand, reading glasses on, in the place of the children, staring as they did, at Hijikata’s ghost.

Can I count the ghosts in this picture? There’s Hijikata’s ghost, or the ghost of his ghost, as you suggest: not there but tangibly so, conjured by your gaze (directed and mediated by the lenses of your glasses and camera, which suggest either anticipation or withdrawal, a picture about to be taken or just missed) and by the indirection and signification of the hyperlink. There’s the ghost of Shibata-san’s youth, invoked in the reversal of her posture and by her amused expression, charmed by the conjuring of her lost self. And then there are the children, whose space your body occupies, or whose absence crowds around you. But your body is the wrong vehicle for their ghosts, because you come to them from across the ocean, an American cousin. Your body conjures the absence of a different ghost in Hosoe’s photograph, a girl from across the ocean — the non-alien, who is not-there.

She is from another generation, perhaps an American aunt, but because she was not allowed to age after the camps closed, she must be the same age as the children in Hosoe’s photograph. Go and look for her gaze among their faces, her pose within their bodies, her laughter echoing in the clustering of blackness that holds them loosely, as they wait and watch, in the corner of the print.

In this project, I create photos in order to send postcards from past traces of my present self to a collective future, a cultural commons shared by those who would also trace their bodies’ movements through their reimagined pasts.

I take these pictures to speak with Hijikata, Hosoe, and other butoh artists and photographers.

I also make these photos to show my parents, to prove to them that I remember what they taught me.

I display these images in public, to send a message to my Grandpa, that he’s still teaching me how the world works.

In hindsight, reflecting on my family’s photos, they had everything to do with producing evidence of our American ness. My uncle as a four year old in his Hopalong Cassidy outfit and twenty years later in his U.S. Army outfit, heading to Vietnam. Summer BBQ picnics at Huntington Beach. My grandparents’ anniversary cake. My engaged parents posing with their Dodge Charger. My Japanese American little league baseball and basketball teams.

When Japanese Americans, alien and non-alien, were first herded under armed guard to indefinite detention, they were not allowed to bring cameras. So, after camp, every camera is haunted by the cameras that were confiscated, and every photograph is haunted by the images that could never be taken.

The specificity of these absences inheres in a highly photographed and mediatized historical memory. There are iconic images by acclaimed photographers, like Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, and rich archives of pictures taken by War Relocation Authority photographers. Many were Japanese Americans themselves, earnestly or duplicitously employed in producing the propaganda of Japanese American loyalty and American justice, which banished the non-alien from perception.

And then there are the brave, cunning, or reckless incarcerees — Toyo Miyatake, Dave Tatsuno, George Hirahara, and others — who built or smuggled in cameras, equipment, and, in one case, an entire secret darkroom, eventually convincing the authorities to approve or turn a blind eye to their activities.

The non alien does not appear in any of these photographs.

The Issei and the Nisei loved their cameras, and before and after the war, they actively participated in the artistic development of the medium. My grandfather, Vince Tajiri, was among the legions of camera mad Nisei who documented life on the West Coast and in the post camp resettlement in Chicago, before he made his name as the photo editor of Playboy. Growing up as a Yonsei, I knew nothing of this. I just had a vague idea of the stereotype of Japanese tourists with their cameras, back in those days before everyone was constantly taking pictures of everything.

Maui. Land of my paternal grandfather’s birth. His parents, as tens of thousands of native Japanese did, came over as agricultural laborers. Neither indigenous nor exactly colonizers. Party to the latter, sympathetic with the former. My great-grandfather made highly efficient and durable irrigation flumes for the Alexander and Baldwin Company, which for the moment still retains overwhelming water rights on the island, despite no longer harvesting the land.

It’s complicated. Invited as a guest artist to the island, I’m trying my best to decolonize my dancing body. Channeling the non-alien, do I step onto Maui as a settler or non-settler? I feel my grandfather’s wanting and not wanting to be here.

Grandpa Sakamoto’s rebellious streak started early. Despite being the middle child of three in a Buddhist family, he went to St. Anthony’s, a Catholic school, and changed his given name from Motoshi to Michael. In his youth, he wanted to be a merchant marine, so he skipped class regularly to earn money gambling, quit school at fourteen years old, left home at sixteen, and managed to get onto his first ship at eighteen, in 1930, just as the Great Depression came into full swing. Grandpa worked at sea, in and out of port towns around the country, and also moved as a migrant farm laborer throughout California: Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, San Diego, Salinas, King City, Marysville, Tulare, Yuba City, Modesto.

Eight decades later, I follow his lead…

What are the stories that water tells? In All I Asking for Is My Body, his classic novel of prewar Hawai‘i, Milton Murayama found a key to the social order of plantation life in its sewage system, which literally flowed downward through the racial and ethnic hierarchy of plantation labor. The racial paradise that Japanese Americans from the continent sometimes fantasize about is, from this local vantage, built on an empire of shit. [21]

An immigrant’s genius for irrigation: this story, passed down in your family, is familiar among Japanese Americans on the continent. The Issei immigrated as agricultural laborers, but many were skilled farmers, who’d seen better days and dreamed of their return in the new country. Despite laws barring Asian immigrants from owning land, they leased farms or bought them in their children’s names. The land they cleared and the crops they grew demanded labor that white men refused, and their superior knowledge of irrigation allowed them opportunities for economic advancement before the war.

Most Issei lost everything in the war, and the dominant motifs of stories about the concentration camps are about dryness — dust, wind, and heat. Yet even in those desolate landscapes, the Issei created gardens, orchards — even decorative ponds.

But who was on the land before the Issei were employed to clear it? In Hawai‘i as on the continent, Japanese American lives have been built within the dominion of settler colonialism. Stories about water look very different for Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders, for whom the sea can be as much a home and source of connection as the stolen land. [22]

On December 7, 1941, Grandpa Sakamoto is in the Panama Canal on a merchant ship laboring as a fireman, shoveling and stoking coals in the boiler room. He’s called to report to the officers, who place him in the brig with the other Japanese Americans onboard. He spends the next month behind bars as a “security risk,” then returns to Los Angeles just in time for the relocation order.

Grandpa is reunited with an old flame while being held with thousands of other Japanese Americans in the horse stalls of Santa Anita Racetrack. They end up in Manzanar concentration camp together and marry in 1943. My dad is born in early 1944, seven months before they are allowed to leave eastward for Chicago.

Over a half-century later, I drive past the Manzanar ruins numerous times each winter on my way to snowboard at Mammoth Mountain. I never stop, though, until years later when I go to photograph. Gazing into the distance in every direction, I imagine my grandparents, daring to bring new life into such conditions, imagining a future beyond the horizon. Like my great-grandparents, arriving in Hawai‘i with almost no money, daring to build a new life at the furthest point on the planet from any continent.

There’s nothing there… Ikuzo (Let’s go).

Like your father, you and I are camp-made. It isn’t even necessary for you and I to know this. Still, as a Japanese American, you find your body drawn towards camp, the way one’s fingertips idly linger upon a scar. The camp pilgrimage: it is a rite of movement, a performative genre, an aesthetic counter-training.

The first organized pilgrimages to sites of Japanese American incarceration began in the late 1960s, as an offshoot of the Asian American movement. The fifty-year-old annual program at Manzanar is the most established, with additional events held at Tule Lake, Amache, Minidoka, Poston, and elsewhere. Pilgrimages have served to reunite incarcerees, honor ancestors, build community, and advocate for historical preservation. Pilgrimages helped drive the redress movement, which won an official government apology and reparation payments in 1988. Since 9/11, American Muslims have often participated as attendees and speakers, and the 2018 events at Tule Lake and Minidoka became a flashpoint for organizing against President Trump’s “family separation” policies. [23]

What the camp pilgrimage enacts is not the memorialization but the mobilization of the past, a rite of movement. In 2016, under the Obama administration, the Tule Lake-born therapist Dr. Satsuki Ina made a widely publicized visit to the Dilley, Texas detention center for immigrant families, highlighting the long-term psychological effects of incarceration via connections to her own experience — she was also held in a facility in nearby Crystal City. In 2019, as part of the Tsuru for Solidarity campaign, she returned to Dilley and to Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, a former detention site for Issei during the war (and prisoner-of-war camp for members of the Chiricahua Apache tribe) that has been designated as an incarceration site for immigrant and asylum-seeking children.

These actions count as camp pilgrimages, as well.

The camp pilgrimage as an artistic genre is also well established. Writers, filmmakers, visual artists, musicians, and performers have imagined and documented the return to incarceration sites as a way of taking measure: of the passing of time and the immediacy of trauma; of progress, redress, and their limits; of what is excluded from justice’s dominion, and what eludes it.[24]

One classic of the genre, a 1991 experimental documentary by Rea Tajiri, History and Memory: For Akiko and Takashige, is also a touchstone for me for personal reasons — the filmmaker is my aunt. In response to her mother’s aversion to speaking about her experiences in camp, she layers Hollywood film and WRA propaganda with family interviews, poetic reflections, and fictional scenarios. Finally, Tajiri travels to Poston herself, reenacting a fragment of memory — filling a canteen with water under the desert sun — to construct an image to accompany her mother’s words.

My aunt’s film was part of a cohort of related works emerging after the passage of redress in 1988, including the more idiosyncratic “Return to Manzanar,” a 1996 article by Martin Wong and Eric Nakamura for their groundbreaking zine, Giant Robot, which documented their attempts to go skateboarding at the camp site. These works were also part of the last wave of an insurgent multiculturalism, rising through the 1980s, which was about to be appropriated to provide the governing language of U.S. global power’s rule-over-difference in a post-Soviet world. Like a better-known video from 1991 — George Holliday’s camcorder footage of the LAPD’s vicious assault on Rodney King — History and Memory constitutes an inquiry into the aesthetic conditions under which racist state violence vanishes, or is perceived, before the advance of justice.

Your Manzanar photography, consciously or not, follows in the tradition of these works. (The spot where you are running, I believe, is one of the few spots where Nakamura and Wong managed to do much skating.) Similarly, your work falls within a cohort of projects emerging after the Black Lives Matter movement and the resurgence of white nationalism exposed the collapse of the multiculturalist consensus. The task given to these works is an aesthetic counter-training, pressing against the limits of perception as it confronts the visuality and kinesthetics of racialized embodiment.[25]

The motivation behind every camp pilgrimage, conscious or not, is the conjuring of the non-alien, the desire to feel her impossible presence and insecurable release. She is not-there in your photos, a tangible absence in the Manzanar landscape, delighted, exultant. But she is not haunting your body: the spirit that possesses your movements is not her.

Whether this is your Kamaitachi, or something else, I cannot say. Is it a spirit from prewar Japan, cast out by the devastations of war and occupation? Or is it the ghost of a lost Japanese America, laughing with the restless humor of frustrated migrant farmworkers, dancing out of the segregated, black-brown-and-yellow urban spaces of a forgotten West Coast?

But, no, she couldn’t call me Jesus

I wasn’t white enough, she said

And then she named me, Kung Fu

Don’t have to explain it, no, Kung Fu

Don’t know how you’ll take it, Kung Fu

I'm just trying to make it, Kung Fu– “Kung Fu”, Curtis Mayfield (1974)

In Richard Rodriguez’s book, “Brown,” he speaks of growing up infused with white desire, confessing, “As a young man, I was more a white liberal than I ever tried to put on black” (Rodriguez 25). Highlighting the ghettoization concomitant with his success as a Brown author — “The price is segregation” (26) — Rodriguez speaks of his early resistance to what he perceived as Black literature’s obsession with blackness at the price of a broader reach: “Neither did I seek brown literature, or any other kind. I sought Literature — the deathless impulse to explain and describe. I trusted white literature, because I was able to attribute universality to white literature, because it did not seem to be written for me” (27).

Growing up in East Los Angeles, I noticed that the Mexican Americans and Asian Americans around me also took it a step further. In our desire to “make it” and be “down” at the same time, we wanted it both ways: white values, black style. And for many Asian Americans, raised to be “good Americans,” school and hip-hop are like a model minority version of church and the blues for African Americans. We may not have a diamond in the back of a great big Cadillac but perhaps that’s because we’re cool with the sunroof on a lowered Acura instead.[26]

Perhaps the first butoh artists abroad felt the same or were at least given the opportunity to assume a likewise stance: a favored foreigner. France was the first place outside Japan where former students of Hijikata performed explicitly and independently under the butoh label. At the time, with a renewed fascination and exotification of things Japanese rooted in a relatively ahistorical ignorance, many French dance-goers were primed for an enthusiastic response (Pagès). Generally speaking, audiences in Paris were ready to fall in love with what they both perceived and constructed as a gorgeously grotesque, inscrutable other.

With such lineage, I’ve often wondered how much easier it’s been for me to position myself as a Western butoh artist with this Asian body. Is it a privilege I exercise, or simply a conveniently other ed frame within which whiteness keeps placing me with each new ahistorically perceived, intercultural collaboration I develop with ethnic, linguistic, and international artists different from my own disciplinary and racial identity?[27] Sometimes I’m not sure who exactly is defining the sparkle of this dance ghetto fabulousness in which I’m repeatedly allowed.

In 2001, I applied for an emerging choreographer fellowship. I naively accepted the grant manager’s request to have a desk review of my work samples. I read later in the notes accompanying my rejection letter that my work is “not butoh.”

As Yonsei in the U.S., you and I are given to believe that one must choose between blackness and whiteness — between black style and white privilege — in which case, the desire to have it both ways seems at once logical, ethically questionable, and comically hopeless. The third choice — to become Japanese — would satisfy everybody, except, of course, actual Japanese people, and ourselves. Inauthenticity is the condition of being a Yonsei, because the truth about Japanese American culture is difficult to hear and has nothing to offer to that hunger for knowledge of difference that motors the reproduction of American whiteness.

What’s more Japanese American than a zoot-suited, duck-tailed Nisei pachuke prowling the streets of Chicago in 1945, emissary of styles associated with his L.A. Mexican American and African American friends, distilled through the experience of camp? [28] What’s more Japanese American than an earnest advocate of government-approved resettlement ideology who preaches assimilation to white-identified norms, in a Chicago swelling with Southern black migrants working in war industries? What if they are sometimes the same person, an upstanding, upwardly mobile, proto-model minority during the week, but a little bit yogore on the weekend? [29]

Was it inauthentic for the Mexican American teenager Ralph Lazo to run off to Manzanar, and live there for years as an incarceree, in solidarity with his high school friends? Was it inauthentic for a young Harlemite, Malcolm Little, to evade the draft by spreading rumors of his desire to enlist in the Japanese military, decades before he acquired fame, and an Afro Asian politics, as Malcolm X? [30] Speculative appeals to Japanese culture, often wholly appropriated from Anglo-American Orientalism, helped shape African American political and cultural modernisms. [31] Why should Japanese American culture be any less hybrid than any other racially marked culture grown on U.S. territory?

The surprise, as butoh artists know, is that the demand that positions you as inauthentic may also be a liberating condition of performance. To insist on offering up your own authenticity would be, contra Lazo, to correct and affirm the terms of your own incarceration, whereas to take inauthenticity as an opportunity to dance is to steal away with one’s freedom, at least for a moment, as did Lazo and Little in the Japanese American legends of old.

Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them, only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears.

- Frederick Douglass (Douglass 9)

In the continuing saga after four centuries of chains, whips, guns, nooses, solitary confinement, class warfare, and countless other instruments of oppression and white supremacy, African Americans have fashioned a tool of survival, a gift to American society: the blues. And for Americans of color, facing immigration quotas, continental land grabs, genocide, concentration camps, capital punishment, and the general discounting of their cultural, intellectual, and community values in the workplace and everyday life, the eternal craving for succor embedded in the DNA of the blues is a way of life. As Cornel West explains, the blues speaks to reconfiguring and reversing internalized abjection:

The blues professes to the deep psychic and material pains inflicted on black people within the sphere of a mythological American land of opportunity. The central role of the human voice in this heritage reflects the commitment to the value of the individual and of speaking up about ugly truths; it asserts the necessity of robust dialogue — of people needing to listen up — in the face of entrenched dogma. (West 93)

Thus, for me, as a Japanese American butoh dancer, butoh begins as the blues hidden in the body of postwar Japan. Thousands of Japanese comfort women servicing tens of thousands of GIs fresh off the invading boats. Countless households conspiring to own the Sanshu no Jingi (Three Sacred Treasures): a television, refrigerator, and washing machine.[32] The repeated collapse of every progressive political movement in Japan from the 1940s to the 1970s. The simultaneous retreat into the body and subjectivity in both avant garde and popular culture.

This is the root of our lineage. As such, I ask myself, What is my blues?

My blues is my grandma’s habit of not putting enough green tea leaves in the pot, decades after living in an American concentration camp.

My blues is my single mother never correcting our white landlord for calling her the wrong name for ten years.

My blues is a former research university employer labeling my auto-ethnographic, black vernacular-rooted scholarship on butoh and hip-hop as “parochial” and only existing to legitimate itself, and as “cool” and “hip” at the expense of “a more nuanced treatment” of these practices that I’ve performed on international stages for decades.

My blues dreams of a better time, off in the future, relying on the past.

My blues sings with limbs, fingers, toes, lips, tongue, eyes, ears, hips shaking, neck craning, back breaking.

My blues wants to hear your song, the one that kills.

The blues is often invoked as a figure of timelessness, a dusty path forked away from the advent of modernity, but the blues has a history. Like Jim Crow, it’s a post-slavery, post Reconstruction phenomenon, a conscious updating of tradition that comes into its defining form in an era of U.S. trans-Pacific imperialism. Hawaiian guitar, for example, had already been absorbed by the African American cultural practices that gave birth to the blues.

The historicization of the blues that seems most pertinent to me, however, is postwar — the varieties of electrified blues created and enjoyed by black migrants into cities like Chicago, Detroit, and Houston. In this music, contemporaneous with the dramatic transformation of the conditions of life in Japanese America and Occupied Japan, you see the same complicated relation between the elusive opportunities of postwar prosperity and the living memory and ongoing evidence of historical trauma. If the blues in general can be understood, not as a feeling of despair, but as the exuberant plenitude or overflowing universality that one may discover on the far side of despair, what characterizes this particular variety of the blues, for me at least, is the trick it plays with time. When the past is a precipice, and the future a promise you can’t resist even though you know better than to believe, it takes just the slightest gesture to redirect the train of time onto a separate track, running like a ghost out towards the infinite.

“the true blues singer got a whole repertoire”

— Mosquito (Jones 1999: 476)

But just as I reached the other side, I stumbled, and the movements, the attitudes, the glance of the other fixed me there, in the sense in which a chemical solution is fixed by a dye. I was indignant; I demanded an explanation. Nothing happened. I burst apart. Now the fragments have been put back together again by another self.

— Frantz Fanon (Fanon 257)

In Fanon’s essay, “The Fact of Blackness,” he writes from that liminal place experienced by countless post-colonials and people of color, the same void in which Hijikata made a home for butoh. It’s that hole in your chest that won’t heal. A feeling. To want to be well-liked. To desire a place amongst a dominant population or racial identity, perhaps even by seeming invitation, yet learn that this desire is in vain. And to have to find other means to pick up the pieces. To take half a lifetime to recompose mind, body, and soul.

Fanon characterizes this feeling through the metaphorical image of being objectified by the white gaze on a train, perhaps to nowhere:

In the train, it was no longer a question of being aware of my body in the third person but in a triple person. In the train I was given not one but two, three places. I had already stopped being amused. It was not that I was finding febrile coordinates in the world. I existed triply: I occupied space. I moved toward the other… and the evanescent other, hostile but not opaque, transparent, not there, disappeared. Nausea… (258 -259)

I know this. That debilitating knot in the pit of my stomach when I try and move onstage. Stand without standing, I always tell my students. Usually, only a couple of them get it. The ones who are frozen in terror, whose bodies can’t help but admit it. That’s the stuff, what simultaneously impedes and compels movement in my butoh.

Like Fanon’s triple being, like the Japanese American non-alien, my butoh lies beyond the double-consciousness of code switching, in that place where you realize no multiplicity of tongues or masks will do you any good. Not matter how real you are. No matter how well you earn a place at the table. No matter how much they seem to be there for you. It’s all a mirage.

They just don’t want you.

And so we dance.

What the stillness of the photograph cannot capture, it may yet release. To be excluded from history is also to vanish from a regime of perception. The non-alien cannot be apprehended by the senses. If she makes herself known, it is only in movement.

[1] Referencing/inverting the titular maxim from the second album by Funkadelic, Free Your Mind… and Your Ass Will Follow, Westbound WB 2001, 1970.

[2] For an explanation of the name’s socio cultural and historical root, see Michael Sakamoto, “Michael Sakamoto and the breaks: revolt of the head (MuNK remix)”, pp. 525 532 in The Routledge Companion to Butoh Performance, Bruce Baird and Rosemary Candelario, eds. London and New York: Routledge/Taylor and Francis Group.

[3] The essay, “Inner Material/Material,” from which this quote is drawn, was written for the program of the dance concert, Dance Experience, in July 1960.

[4] See Ishizuka 67-68.

[5] “[T]he war” always means World War II.

[6] See Azuma 138-39.

[7] VS: Like “artist and scholar”? MS: Yes, like being simultaneously allowed not to mean what you say or rather, to mean multiple things and being expected by whiteness to be, as one dance scholar criticized me for not being, “accessible to the widest possible audience.” VS: Artists of color know the price they must pay for opacity, that they are suffered within historically white cultural institutions on the basis of their performance of transparency, a special case of the general paradoxical condition of racial invisibility and hypervisibility. This demand is disingenuously excused by the mystifications of a false populism (the artist of color must speak to the people), and negotiated through the further development of a sophisticated, polyvalent mode of address, some next level shit in comparison to what Henry Louis Gates, a master practitioner, once translated as signifying. No wonder that so many black experimental poets, like Fred Moten and Evie Shockley, manage to negotiate the dilemmas of the scholar artist position with grace — the impossible is already their domain.

[8] The “no no boys” were named after their answers to two impossible questions, nos. 27 and 28, on the Application for Leave Clearance form — better known as the “loyalty questionnaire” — administered by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), the civilian agency in charge of US concentration camps for Japanese Americans during the war. The questionnaire facilitated the processing of incarcerees into “loyals” and “disloyals.” The latter were “segregated” into the camp at Tule Lake, while the former were the objects of the WRA’s program of rehabilitation, of the reconstruction of the image of Japanese Americans as loyal citizens, and, ultimately, as a model minority. This program of rehabilitation, a benevolent paternalism and murderous love, continues to the present day. “Loyals” and “disloyals” were always false projections, fictions coerced to walk and breathe, no and no.

[9] The term “non alien” is a government euphemism for birthright citizens, best known from the now iconic Civilian Exclusion Orders posted in West Coast communities, demanding the appearance of all “persons of Japanese ancestry, both alien and non alien.” The Japanese American Citizens League currently recommends that the euphemism “non-alien” be replaced with the more accurate term “US citizens of Japanese ancestry” in their poignantly titled Power of Words Handbook: A Guide to Language about Japanese Americans in World War II, Understanding Euphemisms and Preferred Terminology.

[10] “We can agree, I think,” writes Toni Morrison, “that invisible things are not necessarily ‘not-there’” (1989: 11).

[11] For a fuller exposition of the socio-politics of the post-World War Two era in Japan, see Dower.

[12] Hosoe: “Anyway, so that was my personal document of my memories as well as Hijikata’s, and hopefully it would give just ordinary people think that those were part of their memories.” (2010)

[13] Jim Kelly was an African American martial artist and movie actor, most famous for his role as Williams in the Bruce Lee film, Enter the Dragon (1973).

[14] Cheryl Song was a Chinese American dancer on Soul Train from 1976 to 1990.

[15] KJLH, KGFJ, and KDAY are long-running black radio stations in Los Angeles.

[16] That is, in the eyes of the state, in a regime of perception authorized by the state, whose categories of race and ethnicity were remade, once upon a time, by radical social movements identified with the Third World.

[17] I first encountered the non-alien, as a theoretical figure and spectral presence in Japanese American history, in a reading of Hisaye Yamamoto’s short memoir, “A Fire in Fontana,” about her experience working at a black newspaper in LA’s Bronzeville/Little Tokyo neighborhood after the war. In that reading, the non-alien emerges as a mysterious agency lodged in Yamamoto’s “innards,” who releases a narrative of postwar Japanese American racialization as a simultaneous severing from African Americans and the irredressable violence of wartime incarceration. See Schleitwiler 245-47.

[18] Oxford, Cambridge, Merriam Webster, and dictionary.com on October 30, 2018.

[19] Elsewhere, I have written about how this justification is produced through what I term an aesthetics of racial terror. See Schleitwiler 9-10, 58-67.

[20] To list these names in this way is ethically unacceptable. I find it impossible to see how repeating their names might bring them justice, and I am certain that doing so bears forward the work of their killers, a violence through which you are called to perceive the world and your place within it. But to refuse to say their names is no less unacceptable. It is the world you and I are in that is in the wrong, the world where they are not, and no one has figured out yet how to put it right.

[21] “The camp, I realized then, was planned and built around its sewage system. The half dozen rows of underground concrete ditches, two feet wide and three feet deep, ran from the higher slope of camp into the concrete irrigation ditch on the lower perimeter of camp. An outhouse built over the sewage ditch had two pairs of back-to-back toilets and serviced four houses. Shit too was organized according to the plantation pyramid. Mr. Nelson was top shit on the highest slope, then there were the Portuguese, Spanish, and nisei lunas with their indoor toilets which flushed into the same ditches, then Japanese Camp, and Filipino Camp” (1988: 96).

[22] See, e.g., Hau‘ofa, “Our Sea of Islands,” in We Are the Ocean.

[23] For example, this Washington Post op ed video, featuring interviews with Dr. Satsuki Ina and Karen Korematsu, was shot by Konrad Aderer at Tule Lake.

[24] Although one might speak more broadly of representations of the experience, like Miné Okubo’s 1946 graphic memoir, Citizen 13660, or of narratives that figuratively enact a return to camp, like Janice Mirikitani’s and Lawson Inada’s 1970s poetry, or recent works by Karen Tei Yamashita, Tamiko Nimura, and Brandon Shimoda, what interests me particularly is the pilgrimage as a performative genre, activated by placing one’s body in what remains of an incarceration site and capturing its image.

[25] A thorough accounting of these works will have to wait, but should include are director Daryn Wakasa’s fictional horror short, Seppuku; musician Kishi Bashi’s “song-film,” Omoiyari; Julian Saporiti and Erin Aoyama’s multimedia concert, No-No Boy; Japanese Canadian photographer Kayla Isomura’s The Suitcase Project; and My Shadow Is a Word Writing Itself Across Time, a four-channel video installation by the Afghan American artist Gazelle Samizay, with poetry by Sahar Muradi, which comes as close to capturing the perspective of the non-alien as anything I’ve ever seen.

[26] William DeVaughn’s “Be Thankful for What You Got” (Roxbury RLX 100, 1974) is a classic old school cruising classic for POC in the hood. Asian American low riders tend toward Japanese cars.

[27] Since 2012, I have created and toured evening-length, stage performances with African American, Thai, Cambodian, Vietnamese American, and Ukrainian American artists working in hip-hop, postmodern, classical, and folk dance.

[28] See Wu, Chapter 1.

[29] Yogore, literally meaning dirty, referred to petty criminality, sexual aggressiveness, and a general disreputability associated with a multiracial urban youth culture on the West Coast. The term also carried a racialized connotation that drew upon Japanese American prejudices against African Americans, Mexican Americans, and Filipino Americans.

[30] See Lipsitz.

[31] See, e.g, Schleitwiler, Chapters 1 and 4.

[32] This was a play on the eponymous sword, mirror, and jewel granted to each successive Emperor of Japan upon their enthronement.

Azuma, Eiichiro. Between Two Empires: Race, History, and Transnationalism in Japanese America. Oxford, 2005.

Bacharach, Burt, and Hal David. “Message to Michael”. Scepter Records JX 11165, 1966, 7” single.

Currie, Dock. 2014. “Must we Burn Virilio? The App and the Human System.” The Imaginary App, MIT Press. 83 97.

Douglass, Frederick. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. New York: Dover Publications, 1995.

Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. W. W. Norton & Co./The New Press, 1999.

Fanon, Frantz. 2009. “The Fact of Blackness.” Theories of Race and Racism: A Reader, Edited by Les Back and John Solomos, Routledge, pp. 257 266.

Fukase, Masahisa. Yohko. Asahi Sonorama, 1978.

Goldsby, Jacqueline. A Spectacular Secret: Lynching in American Life and Literature, University of Chicago Press, 2006.

Hau‘ofa, Epeli. 2008. “Our Sea of Islands.” We Are the Ocean: Selected Works, University of Hawaii Press, pp. 27 40.

Hijikata, Tatsumi. “Inner Material/Material.” The Drama Review, vol. 44, no. 1, pp. 36 42.

Hosoe, Eikoh. Personal Interview. 2010.

Ichioka, Yuji. The Issei: The World of the First Generation Japanese American Immigrants, 1885 1924. The Free Press, 1988.

Ishizuka, Karen L. Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties. Verso, 2016.

Jones, Gayl. Mosquito. Beacon Press, 1999.

Kincaid, Jamaica. My Garden (Book). Farrar Straus Giroux, 1999.

Lessig, Lawrence. Free Culture. The Penguin Press, 2004.

Lipsitz, George. “‘Frantic to Join . . . the Japanese Army’: The Asia Pacific War in the Lives of African American Soldiers and Civilians.” The Politics of Culture in the Shadow of Capital, Edited by Lisa Lowe and David Lloyd, Duke University Press, 1997, pp. 324-53.

Marshall, Jonathan W. “Bodies at the Threshold of the Visible: Photographic Butoh.” The Routledge Companion to Butoh Performance, Edited by Bruce Baird and Rosemary Candelario, Routledge, 2018, pp. 158-170.

Mayfield, Curtis. “Kung Fu.” Sweet Exorcist, Curtom CRS 8601, 1974, LP.

McCarthy-Jones, Simon. “Are Social Networking Sites Controlling Your Mind?” Scientificamerican.com. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-social-networking-sites-controlling-your-mind/. Accessed 3 September 2019.

Mitchell, W.J.T. 2010. “Reading the Image World? Playing with Pictures? Looking Beyond Words and Pictures? An Interview with Professor W.J.T. Mitchell by Sheng Anfeng”. Tsingua University, 2010.

Moriyama, Daido. 1972. A Hunter. Chuo Koron-Sha, 1972.

Morrison, Toni. “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature.” Michigan Quarterly Review, vol. 28, no. 1, 1989, pp. 1-34.

Murayama, Milton. All I Asking for Is My Body. University of Hawaii Press, 1988.

Nakahira, Takuma. “William Klein.” Provoke: Between Protest and Performance: Photography in Japan, 1960 1975, Steidl/Le Bal/Fotomuseum Winterthur/Albertina/The Art Institute of Chicago, 2017, pp. 362 367.

Nelson, Prince Rogers. “Clouds.” Art Official Age, Warner Brothers/Paisley Park Records, 2014, CD.

Pagès, Sylvian. 2018. “A History of French Fascination with Butoh.” The Routledge Companion to Butoh Performance, Edited by Bruce Baird and Rosemary Candelario, Routledge, pp. 254 261.

Rodriguez, Richard. Brown. Viking, 2002.

Sakamoto, Michael. An Empty Room: Butoh Performance and the Social Body in Crisis. 2012. Dissertation.

Schleitwiler, Vince. Strange Fruit of the Black Pacific: Imperialism’s Racial Justice and Its Fugitives. New York University Press, 2017.

Srnicek, Nick. “Auxiliary Organs: An Ethics of the Extended Mind.” The Imaginary App, MIT Press, pp. 69 82.

Tomatsu, Shomei. Chewing Gum and Chocolate. Aperture, 2014.

Wu, Ellen D. 2014. The Color of Success: Asian Americans and the Origins of the Model Minority. Princeton University Press, 2014.