from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Fri, Feb 16, 2018 at 8:32 AM

Dear Morag,

I recently proposed an article/series of walking scores for the journal associated with Performance Studies International, Global Performance Studies (you can find the original call here). They’ve asked me for a counter-proposal that focuses on the “very pertinent conversation about disability and walking” with a focus on creating a set of walking scores/instruction.

Shawn (one of the editors) sent me an excerpt from Examined Life (2009), a conversation between Judith Butler and Sunaura Taylor that covers walking and disability among other things. In the video they mention interdependence, something Dee Heddon and Sue Porter also stress in their Walking Interconnections (2013) project, where they paired disabled and able-bodied participants to go on walks. Reflecting on this it seemed imperative to bring in a collaborator, and I immediately thought of you.

The call asks what bodies might access the future, how they are inscribed in the future, and ‘how performance produces and represents contingencies and possibilities for the future’. I am interested in how artistic medium of walking can open up these possibilities. Walks that create more walks. I think we both agree that that the act of going for a walk must be at the centre of any critical walking discourse. The medium isn’t purely conceptual, it is a mode of praxis that articulates ideas and produces new ones. One of the pieces created as part of Heddon and Porter’s project was a verbatim audio-play Going for a Walk (2013). It brought the walked experiences to life through a new walk. I am interested in the generative potential of walking. How the walks of Butler and Taylor, or Heddon and Porter can spur us to new walks, which can in turn generate future walking practices.

If you’re interested, I propose we use the Butler and Taylor as a catalyst for digital walking exchanges in response to the call. Eventually we can collate these or transform them into some more polished response? Hopefully whoever encounters the resulting text will become authors of new walks, based on the prompts we’ve provided. I think this is how we build the future: through considered, interconnected and generative practices. But to manifest the future, people must first have access to it.

Let me know if this sounds interesting and we can work out the details! Hope you are well.

Best,

Blake

Invite someone who walks differently than you to go for a walk.

Choose a place to walk together in the future. Pick a date.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Fri, Feb 18, 2018 at 9:32 AM

Hi Blake,

Thanks so much for the invitation to walk with you. As a first step I would like to say an enthusiastic yes: on a personal, political and professional level I believe categorically that we must make actually walking crucial to any critical discourse on the subject. I’m constantly trying (and stumbling in different ways) to integrate my academic, artistic and activist work with everyday experiences and to put that into words, so this exercise sounds intriguing.

I think the generative potential for walking operates in several ways. My own practice owes much to the Lettrist/Situationist idea of psychogeography, which transforms walking into activism of sorts. I’ve been experimenting with what this might mean for over a decade now, primarily with The LRM (Loiterers Resistance Movement), a collective I founded in Manchester in 2006. On the first Sunday of every month we facilitate a free communal wander, open to anyone curious about the potential of public space and unravelling stories hidden within our everyday landscape. My first creative walking experiments were a way to begin to try and understand the city, to find my place and to prove the streets are ‘made for more than shopping. The streets belong to everyone’.

The origin of psychogeography makes the political intent clear. It was born within the twentieth century avant-garde milieu of The Lettrists and Situationist International, although many contemporary mutations often feel very detached from these radical roots. Broadly, it aims to reconceptualise walking as a way to affectively remap the city, revealing both hidden power lines and provoking new ways of critically engaging with space. Rather than an instrumental A to B walk, a psychogeographic dérive (or drift) is guided by instinct. It may utilise a ludic device such as dice, playing cards or a creative script, which jolts one out of habitual movement to inspire new ways of experiencing the everyday landscape. Imagination creates a new space, rupturing banality, and starting new conversations with people and place. Although only temporary, they can have resonances which linger, new layers added to the palimpsest and new visions waiting to be made manifest.

I am particularly interested in taking political theory onto the street because it is a place of serendipity and potential re-enchantment. The pavement is one of the few opportunities for casual, embodied encounters with difference. Contrary to tabloid hysterics, the flow of everyday cosmopolitanism – what Jane Jacobs (1961) calls “the ballet of the sidewalk” – is generally harmonious. Its joy and grace comes from its very embodiedness, the sights, smells, sounds and feelings that an attentive wanderer can become attuned to. (Of course I am not naïve enough to suggest all is well in all ways, and of course not everyone has equal access to particular streets; I hope we will discuss this later.)

She’s not a psychogeographer per se, but I find myself returning to the work of Doreen Massey and her conception of space as a network of relationships, the threads of which enmesh us locally and globally. In ‘A Global Sense of Place’ (1994)she uses a walk down Kilburn High Street to illustrate her theory, exploring the people, objects and advertisements in her local shops. Crucially Massey never forgets power dynamics, and is attentive to issues of social justice. Her sense of place is progressive, fluid and a tapestry of simultaneous “stories-so-far” (Massey, 2005, 9). This makes clear we can influence the direction the narrative takes, and I believe walking together is one tool to do this.

Massey brings us back to the material, even as she explores the changing nature of time and space. We need an infrastructure to make walking possible, and I think the tension between the abstract and concrete may be another path we return to in this correspondence.

I look forward to seeing where we go together.

Very best wishes,

Morag

2.

Meet your friend at the previously chosen time and place.

Walk together and map the technological supports that provide you access. If there are barriers to access, map those as well.

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Sat, Feb 18, 2018 at 7:48 PM

Dear Morag,

Thanks so much for this. I can’t believe I have never made it to one of the LRM’s first Sunday walks. Somehow Manchester feels very far away in my geographical imagination. I suppose this is what Massey talks about in World City (2007)—the pulled weight of London. It’s the only place in the UK I have actually lived, so it’s particularly central to my experience. My interest in creating distance walking exchanges through digital means actually emerged in some ways from reading Massey. How do we link global places through local walks?

I think we’re on the same page in regard to the importance of actually walking, rather than simply conceptualising it. The focus has to be on creating models of practice. This is one of the things that always excited me about the LI/SI: the foregrounding of a playful constructive practice and their exuberant vision for a new future. Michèle Bernstein talks about how the dérive ‘wasn’t a hobby’, how ‘the SI wanted to make it a way of life’. It was through practice that they would contribute to ‘the social revolution’, replacing ‘the old world with a new one’ (Marcus, 1989, 376). I remain enchanted by their ideas, but I am also aware of the Mierle Leiderman Ukele’s lament from the Maintenance Art Manifesto (1969): ‘after the revolution, who’s going to pick up the garbage on Monday morning?’ The systems we build now shape the base-line for our future.

Did you know it was Bernstein who got Debord’s Society of the Spectacle (1967) published? She convinced her publisher based on the success of her novels, The Night (1961) and All The King’s Horses? (1960). She’s done some interviews more recently, and she talks about how though she didn’t ‘write a lot’, she ‘was speaking a lot with Guy [Debord] in private and in public, sharing ideas’. I imagine they were walking together too. There is this level of support she provides (financially, editorially, conceptually) that still isn’t really discussed.

I’ve been thinking more about the Butler/Taylor. I was really struck by the notion of having to out yourself daily. I relate to this somewhat as a queer who doesn’t immediately read as one… I go through a process of deciding how and when to out myself to different people in different situations. I have more privilege in this than someone with a disability (perhaps an invisible disability) who has no choice but to out themselves in the face of inhospitable environments. My invisibility gives me choices as to when and how I present myself (which comes with its own privileges and frustrations, assumptions and challenges), whereas the invisibility of disability (both in a person and in infrastructure) requires constant outing accompanied by asking (for help, accommodation, access etc.).

How do we take for granted the technologies that support the needs of able-bodied citizens? How do we acknowledge our invisible interdependence?

In response I came up with the following prompt:

Identify the technological supports in the landscape that provide access in your everyday walks. If there are barriers to access, identify those as well.

Best,

Blake

3.

Walk apart from your friend. Look for absences: who is not where you are and why?

4.

Keep an eye out for supports for other users of the city. As you walk, are there textures, sounds or visual cues that might help or inhibit you if you were in a different body?

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Mon, April 2, 2018 at 6:32 PM

Hello dear Blake,

I used your walk prompt as the inspiration for the LRM first Sunday yesterday, although we deviated somewhat due to external forces. We wandered around Castlefield where there is a network of canals, bridges and the world’s oldest railway line. This transport infrastructure has been generative in shaping the city, and indeed modernity itself, and as citizens we both affect and are affected by the opportunities and connections they provide.

As a commuter I’m resisting the urge to rant about the decline of our public transport system, and the curious nostalgia for steam trains, because we need to focus on walking, which for most people is a taken-for-granted and banal mode of movement. Infrastructure matters here too of course on so many levels and there are conflicts. For example, let’s consider the humble cobblestone. Here in Manchester, as elsewhere, they are celebrated as an important aspect of our heritage; even replica cobbles are more “authentic” and desirable than tarmac to many. However, they are tricky to navigate for many pedestrians, painful for wheelchair users and a problem for cyclists or anyone with a pushchair or trolley. Of course, The SI would advocate ripping up the cobbles to uncover the metaphorical beach below, but I am unconvinced that would be equitable or truly accessible to all. To echo the work by Mierle Leiderman Ukele you mentioned earlier, there will still be cooking, cleaning and emotional labour and we will need a total revolution to be sure they do not fall on the kinds of bodies we have traditionally expected to take on that work.

The LRM manifesto is clear “The Streets Belong to Everyone” but sadly this is an aspiration, not a statement of fact. The erasure of public space through neoliberalism, privatisation and marketization makes it almost a naive hope but I think it’s worth reasserting our rights. I wish pedestrians were centred, and valued, and mundane infrastructures were in place to support them. We’re focused on creative potential here, but there’s obvious health, environmental and sustainability benefits too. Imagine a street that was wide, flat and well maintained, where people did not have to fight for space with bins or cars or hipster a-boards; this shouldn’t be radical or threatening but somehow it is. We need to take a holistic and intersectional view of access too.

We need to take a holistic and intersectional view of access that moves beyond the material too.[1] Recently I conducted a series of walking interviews with women to learn about their pedestrian experiences of Manchester. Woman, of course, is a heterogenous group and our conversations drifted in many directions, but gender remained a key determinant in when, where and how we decided to travel. Women have cognitive maps of places that feel safe or threatening or to be avoided at all costs and these are temporal too; the canal at night feels very different to a sunny lunchtime. These maps are based on personal experiences, stories shared by friends and family, mediated warnings and messages absorbed from a culture that can feel saturated in misogyny. Sometimes we walk together in a loud defiance of this, footsteps become a scream of rage during a Reclaim The Night march or a Slutwalk. More often it’s an everyday resistance, and a range of coping tactics unconsciously adopted; a certain stance, a key in the hand, a quicker pace, because we won’t, can’t let fear stop us from walking.

It isn’t just about gender of course, and women talked about the intersectional issues that changed their experience according to race, age, class, sexuality, appearance and other factors. However, everyone talked about street harassment and abuse received simply because they were a woman. Indeed, on several occasions our interviews were interrupted by men who felt enabled to disturb us with comments or questions about what we were doing. Their interventions ranged from the vaguely humorous to the blatantly offensive but all stopped our conversation and reminded us women can “invite” trouble just by being in space.

Angry as I am, I really like Vera-Gray’s framing of this as an interruption (2016); she talks about how interruptions change the flow of your walk, stealing something from you by breaking your flow and impacting on what happens next. It reflects the spectrum of everyday sexism and the impact it has.

We need solidarity and mutual support to address this and an approach to access that includes action against harassment. When we think about the street what, and who, is absent can be as illuminating as what is visible. Therefore, my prompt for your walks this week is to focus on absences; who, and what, is not where you are and why?

Morag xx

p.s. I suspect you will have seen this, it’s been shared a few times, but I love this, Carmen Papalias Mobility Device (2013).

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Wed., April 4, 2018 at 7:15 AM

Morag,

Thanks for the link to Mobility Device. I know some of Papalia’s work, but hadn’t seen this particular piece, which is great! It illustrates invisibility and interdependency so well. Rather than this focus on hyper-individuality (the white cane) it is an interdependent exploration of his walking ability. It makes the psychogeography of his experience as a blind walker concrete, with the band making audio-visual the support structure that guide him through the city. But it does this by creating this enchanting public event.

Combined with your walking provocation, it really made me think about how textures communicate. I followed your walking instructions on a walk I do quite a lot: from my house to Hollow Pond in Epping Forest.I thought about how the textures of the street create a kind of code for lots of different people. Tactile paving for the visually impaired, beeps for crossing. I have taken advantage of some of these codes as a babysitter: I’ve used these texture changes to help the kids understand when to stop on their scooters.

As I walked I was aware of my access to space other users might not have for a variety of reasons. I crossed a major street where construction has temporarily eliminated all good places for pedestrians to cross. I was aware that not only did I need my legs, but I also needed speed, the ability to go quickly across the street and jump on a dirt filled median. The path I chose to go into the forest is also inaccessible, both in regard to physical access, but also mental access for many users. It leads you off-road into a forest. Part of the reason I take this path is because it is usually empty. It is uninviting. This exclusivity, inaccessibility, is part of the appeal. After I walk through the usually empty part of the woods, I get to one of London’s major cruising grounds. It’s a lot of single men walking about… what someone else might consider lurking. There are almost never any women. Though occasionally families or dog walkers will pass through. Or there will be teenagers drinking or smoking a spliff.

I thought of a walk I did with a woman in Stratford recently and we talked about how she limits her movement. There are certain places she would not go on her own. This is exactly that type of space, especially at dusk, when I was walking. She had a sense that if something did happen there would be a chorus of ‘Why was she walking down there alone? Why did she put herself at risk? Of course it’s terrible, but not surprising considering her behaviour…’

I think these different lived experiences of space are something walking can help identify. I like that Papalia’s work asks people to walk with him. It never feels like he is asking them to perform his disability, but they do have to engage intently with it. There was urgency to the performance. These were real stakes! If they lost focus, he could be in harm’s way. They alerted but did not lead. They walked with him, rather than for him.

Best,

Blake

5.

Create a new code for moving through the city. Take your map and assign each barrier/support a way to move, play, or interact with the city. Be creative and code how you please.

6.

Invite someone to walk with you following your codes.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Thurs, April 5 2018 at 12:32 PM

Hey dear Blake,

Thanks for this. I think walking with, rather than for, is an important distinction. As the slogan says “nothing about us without us.” I wish the social model of disability, which views obstacles as externally constructed, was embedded more widely. It has problematic aspects of course, specifically in its denial of the embodied experience of pain, fatigue and negative feelings, but too often people with disabilities are constructed as a burden. There’s parallels here with Sara Ahmed’s work on the Feminist Killjoy: to draw attention to a problem is to become the problem, and how dare anyone highlight lack of access?

At the heart of so much of my work is a tension between enchantment and the material; we have to deal with the actual conditions needed to manifest the city of our dreams. To misquote Emma Goldman, “if I can’t get up the stairs to join you, it’s not my revolution.”[2] I’m angry there is a need to champion provision of everyday infrastructures that mean people can access their right to be in public space. We should not need to fight (to give just two of many examples) for adequate public toilets or an end to street harassment; these should be accepted as a common good.

Yours,

A proud but angry Feminist Killjoy

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Thurs, April 5 2018 at 9:46 PM

Morag,

Yes, I think intersectional approaches are so important, both in terms of how we shape the future, and how we look at the past. This makes me think of Abdelhafid Khattib’s abbreviated psychogeographic study of Les Halles for the SI’s Algerian section. Abbreviated because he was‘subject to police harassment in light of the fact that since September, North Africans [were] banned from the streets after half past nine in the evening.’ Following two arrests for break curfew he ‘relinquished his efforts.’ It’s one of the few accounts of a Situationist dérive, and it brings attention to external obstacles that restrict walking.

Sharanya Murali (2016) has written about Khattib’s walk, in conjunction with her own experience of drifting in New Dheli. She considers it in relation to ‘disability and other forms of marginalisation’ (206), and how the different obstacles he encounters can be understood in relation to the everyday experiences of barriers and boundaries experienced by disabled drifters.I think her discussion really illuminates how constructed access is. She talks about her failure to complete traditional drifts identifying with Khattib. But I think her text really forwards the idea that these are not failures, but revelations that guide us towards rifts in access.

The editorial note attached to the end of Khattib’s piece ends with the idea that ‘the presentcannot be abstracted from considerations bearing upon psychogeography itself— no more thanafuture politics can.’ This is why the LRM has to meet every month, and our discussion of walking has to be based in the action of going for a walk. And also why it’s necessary to walk with other people, and people who walk in a variety of ways. Context is key, which you miss if you are simply conceptualising a walk. Any conceptualisation of the future must start from the material conditions out of which we are building it.

Best,

Blake

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Fri, April 20 2018 at 10:35 PM

Morag,

Sorry for my radio silence! I am in Huntly for 10 days as a thinker in residence and I will try and think more about this and the social model of disability. Sunday is a 26 mile walk that is completely inaccessible… so should give some foot for thought.

When I arrived to Aberdeen airport to head to Huntly and immediately reminded of another obstacle to access: money. They have cut bus service from the airport so my only options were to walk 45 minutes to the train or pay for a taxi. I walked. Last time I visited I walked to the airport in the pouring rain. Not everyone would have this option. This kind of forced pedestrianism is very prominent in the States where people often only walk because they have no other choice.

I fly back to London on the 29th. When do you leave? Should we meet the 30that noon?

b

7.

Set out and seek traces, layers, clues, ghost signs. How was this place built? For whom? Decode flotsam and jetsam. Perhaps the rubbish will be revealing.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Mon, April 23 2018 at 10:15 AM

Hey dear,

Yes, that works for me, why don’t we meet at the British Library.

I identify with the walking out of necessity. When I was younger I walked because it was cheap, long, boring walks to work or the shops because I needed to save money. Now sometimes I think I walk because I am stubborn, because I was told so many times I couldn’t or shouldn’t. I have the luxury of making that choice and realise how lucky that makes me…

See you soon

M x

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Tue, May 1, 2018 at 7:35 AM

Morag,

Great to see (and walk with you) the other day. Just a quick thought that popped into my head (more thorough thinking to come soon):

I was struck by the fact that my arrival ended your conversation with a stranger, who started speaking to you because of your Loiterer badge, at least I think that was the one… I wonder if in this collaboration your work with LRM and your research on access to urban space, functions as a kind of badge, it makes you inviting. I guess what I am saying here, is that though I started this whole exchange off with an invitation, it is really you who has invited me…

xx

b

8.

Invite an old friend for a walk. Create a new code with them, one only the two of you can decipher.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Tue, May 1, 2018 at 10:07 AM

Blake,

Ah my Loitering badge, yes its provoked many conversations. It was very busy at the British Library that day and (I hate to judge by appearance but it seems pertinent here) a white woman, smartly dressed, grey haired, I guess in her 60s, asked if she could sit in the spare seat at the table where I was having coffee.

She started telling me about an exhibition she had just seen about explorers and it felt like she was tentatively thinking through her perception of colonial legacies; I could almost hear cogs turning as she realised how many sides to a story there are. Power lines made visible and implicating us all; we are all indeed interdependent and entwined.

I love conversations and encounters like this, it’s one of the delights of public space. However, the pleasure is of course contingent on so much. She read both inside the library as safe – of course it is, how much more “civilised” than the British Library? – and judged I was open to her joining me, perhaps because of our visible commonalities. I had the time, inclination and energy for a chat and the security of knowing I was inside a controlled area and waiting for a friend (you could be my escape route!). All this meant the conversation was a privilege and a choice. I contrast this with the uninvited street heckle, the seemingly innocuous “cheer up love” or shouted objectifying “nice tits”. These are not welcome invitations, but I do sometimes wonder what would happen if (for example) one responded to a request to “show us yer gash” with doing just that. I don’t dare test this out. As Butler says in that video (which I love and use frequently in teaching) “a walk can be a dangerous thing” (Examined Life, 2009). To be in public is to make yourself vulnerable and we need to be attentive to who is rendered invisible, unwelcome or unable to take part.

I am not convinced a walk can ever provide a definitive answer on anything – it’s always a state of flux, partial, fluid, but I want my praxis to ask awkward questions, enable difficult questions and uncover hidden stories. Creative mischief! My London is fragmented and fleeting, based often on childhood memories. Traversing the new Granary Square with you we could have been in any shiny modern metropolis, tasteful exclusion, corporate fun and invisible boundaries everywhere. Made me think of Sharon Zukin (1995) and pacification by cappuccino… and I don’t think this is a future that will benefit many.

Good to finish in Hausman’s, a place I love. Radical bookshops are always about so much more than books of course and when I’m in the area I love to have a rummage and pick up a new vision for my train journey home. In the basement the remnants of Doreen Massey’s library were for sale for £1, an online note making clear everything of value has gone to archives. Of course I couldn’t resist and started reading before we even pulled out of Euston. As the world zoomed by the carriage window I traced notes written in the margin.

M x

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Thurs, May 10, 2018 at 8:17 AM

Morag,

I love the image of you tracing Massey’s marginalia, and the idea of picking up new visions at the bookshop. It was great to actually walk with you, which though we always see each other at walking events, I don’t think we’d had the chance to really do. It made it really clear the different embodied experience you bring to psychogeography, which is so often dominated by the experiences of able-bodied men (myself included!).

I’ve been thinking more about the ways we build models for the future. It’s fifty years since May ‘68, and May in the UK is national walking month, sponsored by Living Streets.[3] It’s an admirable endeavour, but I worry it reinforces a neoliberal model of walking, where we walk to and from work and home, or to raise money for a charity, rather than for serendipity and enchantment or to interrogate the construction of the landscape. In some ways it seems a direct contradiction to the spirit of those events. I worry about 68 becoming a heritage event, with nostalgia standing in for creating new ideas and actions in response to contemporary problems.

In your first e-mail you wrote that you’ve been trying to integrate your academic, artistic and activist work. The dérive can be a radical approach, but I don’t think it is necessarily an activist one. The SI’s activism calls for the realisation of art through its suppression, to the point of excluding artists, and I think this is really important in terms of how art and activism intersect. I think Art is better at opening up questions than advocating for specific change… it’s a crucial tool in shaping the future, but I wonder if the conflation of all these terms dilutes them.

At any rate, should we plan a simultaneous walk in London and Manchester? Let me know when you are free, and we can work something out.

Best,

Blake

9.

Meet somewhere else. Walk your code together.

10.

Walk your code apart. Share it digitally. Create a walking instruction for each other.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Mon, May 14, 2018 at 1:34 PM

Hi Blake,

I think creative walking can, and should be, a micro level challenge to those neoliberal forces. We take something instrumental and re-enchant it, opening up other possibilities. If I am feeling especially hopeful I see those cracks we leap over on the pavement as small rupture in what Mark Fisher (2009) calls “capitalist realism”. His work isn’t so far from Debord’s spectacle, linked by the vision of Capitalism commodifying everything, including our desires, our imagination and our visions of the future.

However, I think you are being somewhat harsh to Living Streets as there is still huge value in what they and other pedestrian campaigns do. Perhaps a key tension in my walking art is reconciling intangible potentials with actual material conditions. It’s hard to play on a pavement blocked by cars or covered in broken bottles or full of hostile bystanders. I can’t help but take these personally because my own walking is so often limited or restricted by the environment, and doesn’t it always come back to that embodied experience of moving through space?

As a person with a disability I think the very act of walking creatively, of taking up space, of making a show and a virtue of my necessarily slow walking is resistant and political in a way it isn’t for everyone. When I spoke of gracefulness in a previous email that wasn’t the truth always held in my gait, especially when I trip or fall or collide. Those accidents illustrate our co-dependence; every time strangers help me up and offer kindness… but I’m always acutely aware of the physicality, the stress of movement, and when I’m in pain my feet and routes across the city are recalibrated. Sometimes my dérive is not a joy but determined by a route that avoids steep steps or challenges I don’t want to face, often created by thoughtless design.

Thinking back to our previous conversations, there is a horrible, neo-colonial edge to too much psychogeography, too many claims of revelation, assertations of the one true meaning of a place. This essentialism needs resisting in all its guises, we need to move towards a future that embraces multiplicity. This would be truly radical. I’ve got a lot to say about what Activist means in this context too but I think I will wait till after we walk together. Let’s do it Thursday 17th.

Cheers

Morag

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Mon, May 14, 2018 at 2:27 PM

Dear Morag,

You’re right, I am being too harsh. Organisations like Living Streets are doing the best they can to navigate a system that forces them to prioritise neoliberal goals. The spectacle proleterianizes the whole world and all that.[4] I often tell my students that if they hold their favourite artists to stringent purity tests, they won’t have anyone left to like. I couldn’t even like my own work if everything I did had to hold all the baggage of my past mistakes. I think the key thing here is to grow out of our conditions and our conditioning.

The 17thsounds good. Thinking more about our walk I wondered how we bring attention to all these different codes and their layers of interaction? Maybe we could try to re-code the city.

Best,

Blake

11.

Walk your friend’s instruction.

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Fri, May 18, 2018 at 11:22 AM

Dear Blake

Here’s my fieldnotes:

Instructions:

- If you see a flower stop to smell and then turn around and walk in the opposite direction.

- Don’t follow desire lines, cross them.

- Where slabs change colour, take the first left.

- When you come to tactile bumps, slow down. Even slower. Slower than that.

- Do not go up any stairs without handrails

- Consider potholes or uneven pavements to be a forcefield. You can’t cross them, find a way around.

- Always cross roads at crossings.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

The disorientating whirl – I hadn’t ever appreciated quite how frequently the paving changes – I start to wonder why that is. Some switches are clearly patching up glitches but others seem more deliberate. I feel unexpectedly panicky; am I doomed to circle Piccadilly gardens forever? The gloom descends so swiftly and stealthily, this is not what I imagined.

An acquaintance greets me, breaks the spell and I am glad to see they are a fellow traveller. He asks me what I’m doing and I try to explain; he sends me to Morrisons (although later, delightfully, I realise I misinterpreted). The city feels grey and oppressive, the only flowers I see are plastic or painted or too high up to smell. Finally I spot an abandoned bunch of dahlias stuck in a billboard and they propel me back into queues of people waiting for the bus.

My route is constantly changed by potholes and obstructions, vortexs of unwelcome and I find myself savouring the slowness provided by tactile paving. I shuffle on, and at the these crossings I feel detached, invisible, but strangely self conscious. I am a slightly off copy of me as I weave through the Northern Quarter, not following my heart or my head and biting my tongue when I want to speak beyond the game.

I think of Benjamin’s replications and wonder, fleetingly, if this is what it means to be a flâneur.[5] The phone is keeping me from total immersion and I find my gaze lowered to the textures beneath my feet and the words I clumsily try to type as I push on. I pause at a corner to search for clues. A man rummages through abandoned books and everywhere smells of cooking: chips, curry, traffic fumes.

No children, no blossoms, and a row of neglected buildings waiting to die. They have stained glass windows I will miss. This street aches with the burden of so much unrealised potential and access denied. A road closure means another loop, a circle of decay and decadence waltzing together oblivious. As my battery fades I feel a sense of relief, performance over…. And yet it lingers. I buy a samosa and head to the bus stop, I feel disoriented and overwhelmed by the grey. I retrace my steps and the dishevelled bouquet has gone.

I realise my field report sounds rather gloomy but actually I rather enjoyed the jolt from my own practice, although it made me feel more self-conscious and passive than my usual communal wanders.

I’m glad next month’s First Sunday will be part of We Shall Overcome (WSO), ‘a movement of musicians, artists and community organisers’ that describes itself as ‘a raised fist and a helping hand’ against austerity.[6] It’s an umbrella under which hundreds of local events are organised, and brings people together to celebrate culture, share resources and demonstrate support. WSO is based on principles of mutual aid and solidarity rather than charity and I think that’s really powerful. Austerity is unremitting and all-consuming and it can feel overwhelming, it’s hard to know how to make a meaningful difference and it’s so easy to feel burned out and disillusioned. Neoliberalism thrives on individualism and alienation, the all-pervasive spectacle, and I love WSO for creating an alternative, ‘one event at a time.’

WSO give me hope and, as Rebecca Solnit says, that in itself can be a radical act (and I really want to reclaim that word from tabloid hysterics).

Cheers

M x

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Tue, May 22, 2018 at 9:15 AM

Dear Morag,

It was so great to walk with you at a distance last week. I know what you mean about navigating immersion in the phone and immersion in the walk. It is a very different kind of exchange than the first one we did, when we planned the walks independently based on the others instructions. That seems ages ago. Walking is a slow process.

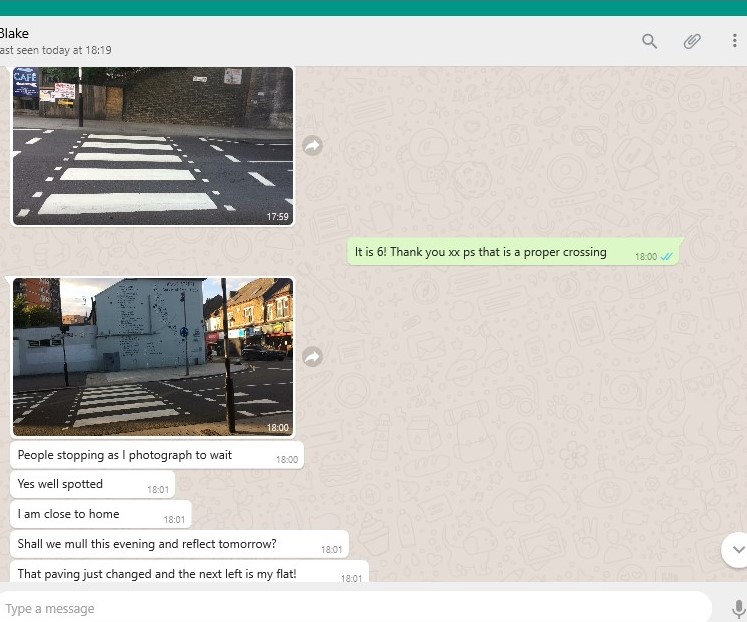

One of the things I am really struck by is that both of our walks led to happenstance encounters. Massey, who you mentioned in one of our first messages, discusses the danger of the digital to reduce the happenstance of walking around the corner and running into a neighbour, someone you know, a moment of alterity. We both experienced the happenstance while walking together digitally: your foray into Morrisons, and my encounter with the woman who wanted a picture (are you a photographer? I see you taking photos. Can you take a photo of me? Make sure I don’t look too skinny!) and the man at the chippie, who I happily gave a fag. I think this leans towards something different than flanerie, though I hesitate to call it a digital dérive.

I have always been interested in how the digital can facilitate us getting out to walk. How can these tools propel us into the present and create new connections for the future (to (re?)engage us with the world around us). Harnessing the use of digital tools to increase these happenstance moments, rather than shut them down is one of the ways walking can help us build the future.

Recoding the city in this way can also help us to identify what we need to advocate for to build a better future together. I loved (loathed) your frustration at not being able to cross and be cross with the building that was being demolished after the sham public consultation. It brings to mind everyday obstructions and how they exacerbate the inability to be seen and heard. If people can’t get themselves to a place, if they aren’t granted the ability to be a community viewpoint, how can they help shape a community’s future?

Walking is a way to bring our attention to these things, to help us identify what lacks, to explore the ‘archaeology of the familiar and forgotten’. But this takes time. Walking is a slow process. Community building and organising is a slow process. The developers know that and refuse provide any.

The street isn’t designed for all of us. I think of an article I read from the 1800s about pram walkers being a nuisance, blocking the road, how they need to get off the street. The street wasn’t built for them. I think of White suburbanites moving to Dominican neighbourhoods in NYC and complaining about the public use of the street, loud music being played into the night. They want the street to be built for them. Quiet, sanitised, unoffensive. This is not Jane Jacob’s vision, it’s more Robert Moses. Orderly and ordered. For the privileged.

This also goes back to something we have discussed before, the privilege of protests and marching, and how a lack of participation in those events doesn’t necessarily betray a lack of radicality. For someone in a wheelchair or walking with crutches, or can’t generally walk long distances, a long march might not be the best way to manifest their protest. The single parent or economically precarious person working three jobs, who doesn’t have the time (or energy, or bandwidth) to engage in this sort of way. Often protests seem to be what manifests this collective will, but is it simply a moment of catharsis? A chance to ignore the issues on the ground that we need to engage?

How do we move beyond an insular audience? How do we invite people in who aren’t already in the know? How do we make this kind of work accessible–in terms of what it is and what its doing. How can walking invite a broader cohort into planning the future, manifesting the future? This all comes back to the framing of invitation I suppose. I think the power of walking lies in the fact that once you’re doing it it isn’t conceptual. It changes the way you look at spaces and the ways you interact with them through practice. But it’s working out how to get past that first step. That’s what walking must start to do if it wants to contribute to the future, if it wants to generate the potential for new relationships between landscape and the people (and non-human actors) with whom we inhabit it.

Best,

Blake

12.

Ask someone to direct you to the heart of the landscape. Get there without using a map or your phone (unless someone draws you a map, in which case that is brilliant luck).

from: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

to: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

date: Fri, May 25, 2018 at 8:22 PM

Dear Blake,

I’m still thinking about how that loop became a vortex, sucking me in and obliterating other routes. I ended up in the Northern Quarter, the frontline in debates about regeneration, heritage and the right to the city in Manchester. This is an urgent matter here but one that can so easily fall into the traps of nostalgia and essentialism when there is talk losing the soul of the city. I’m not immune to this, although I love the city partly because it is always in flux it is heart wrenching to see the demolition of places I love. They are being destroyed for money, the logic of late capitalism that does not care about character or affordable housing and just wants to maximise profits for the few. The same is happening in other places too, although my home town is particular it is not exceptional and there is a horrible inevitability to this “progress”. I do not want my walk to be just of witness or commemoration. I’ve been thinking a lot about what constitutes effective activism and I think it takes many forms but it must always be outward facing, trying to bring in. I’m worried the word radical is being devalued too, reconfigured as a synonym for terrorism and wrapped in Islamaphobia. So many challenges.

Phil Smith (2010, 2015) has articulated beautifully these potentialities throughout his provocative, and often playful, oeuvre. I remember him talking about the need for secret walks, as we need a private space to evade the spectacle… and I think there is much to learn from his idea that we need to create a new mythogeography. I think he usefully reminds us of the need for a critically engaged walking practice as opposed to a leisurely stroll. It’s not enough, but to keep walking together with open minds seems a positive step, and when the odds feel overwhelmingly against us it that cant be bad.

I’m hopeful about where we may go.

Cheers,

Morag

from: Blake Morris <blake@walkexchange.org>

to: Morag Rose <mltrose@thelrm.org>

date: Thurs, May 31, 2018 at 8:29 AM

Dear Morag,

Yes! I try to maintain my radical optimism, but it definitely feels overwhelming at times!

I’ve been reading more of Vera-Gray’s work and I am really attracted by her idea of the conversation replacing the interview. I think this is a space walking talking methods create; the contours of the walk dictate the experience of it and the conversations you have along the way. In framing this project as a conversation with a practitioner, rather than say a series of interviews with walker’s working with issues around disability, it becomes about creating a space of ‘fluid exchange’ and the ‘co-creation of knowledge’ (2017, p. 31). This is what the Butler-Taylor work does so well, and though I don’t think conversation is necessary for works in the medium of walking, I think it’s one of the exciting things about practices that ask people to walk together (even if at a distance…). I suppose it comes back to three things: invitation, conversation, interdependence.

One of the things I think is important is that we engaged in a variety of walking tactics. We integrated walking exercises into already existing plans for walks; we walked in person from the British Library to the radical book shop; and we walked together at a distance through a digital exchange. The walks were generative, playful, constructive. They provided us with a different insight on walking together.

I think we both agree that these ideas can’t remain abstract and that the walking is a flexible way of bringing these ideas into practice. Artistic walking is a mode of praxis. The walk both articulates ideas and produces new ones; it is a continual process of generation. I think that’s why it’s important that this exchange is framed through co-authored walking provocations. Though our independent voices are engaged here in conversation, in the resulting instructions authorship fades in favour of practice. In the case of this publication, the walking scores are what hold the most potential for the future. They offer opportunities for exchange. They further conversation through practice.

And hopefully, like the conversation I started with you, it will continue to expand beyond the limits of this exchange. So thank you for accepting my initial invitation, and hopefully this is not an ending, but the beginning of future walks.

Best,

Blake

13.

Collate the instructions, scores, diagrams, maps, and pictures into a walking guide for someone else. Invite them to try out your guide and make one of their own.