Felipe Cervera

LASALLE College of the Arts

Shawn Chua

Independent Researcher and Artist

Yiota Demetriou

Bath Spa University (UK)

Areum Jeong

Asia Culture Research Institute

Eero Laine

University at Buffalo, State University of New York

Azadeh Sharifi

Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich

Evelyn Wan

Tilburg Institute for Law, Technology, and Society

Asher Warren

University of Tasmania

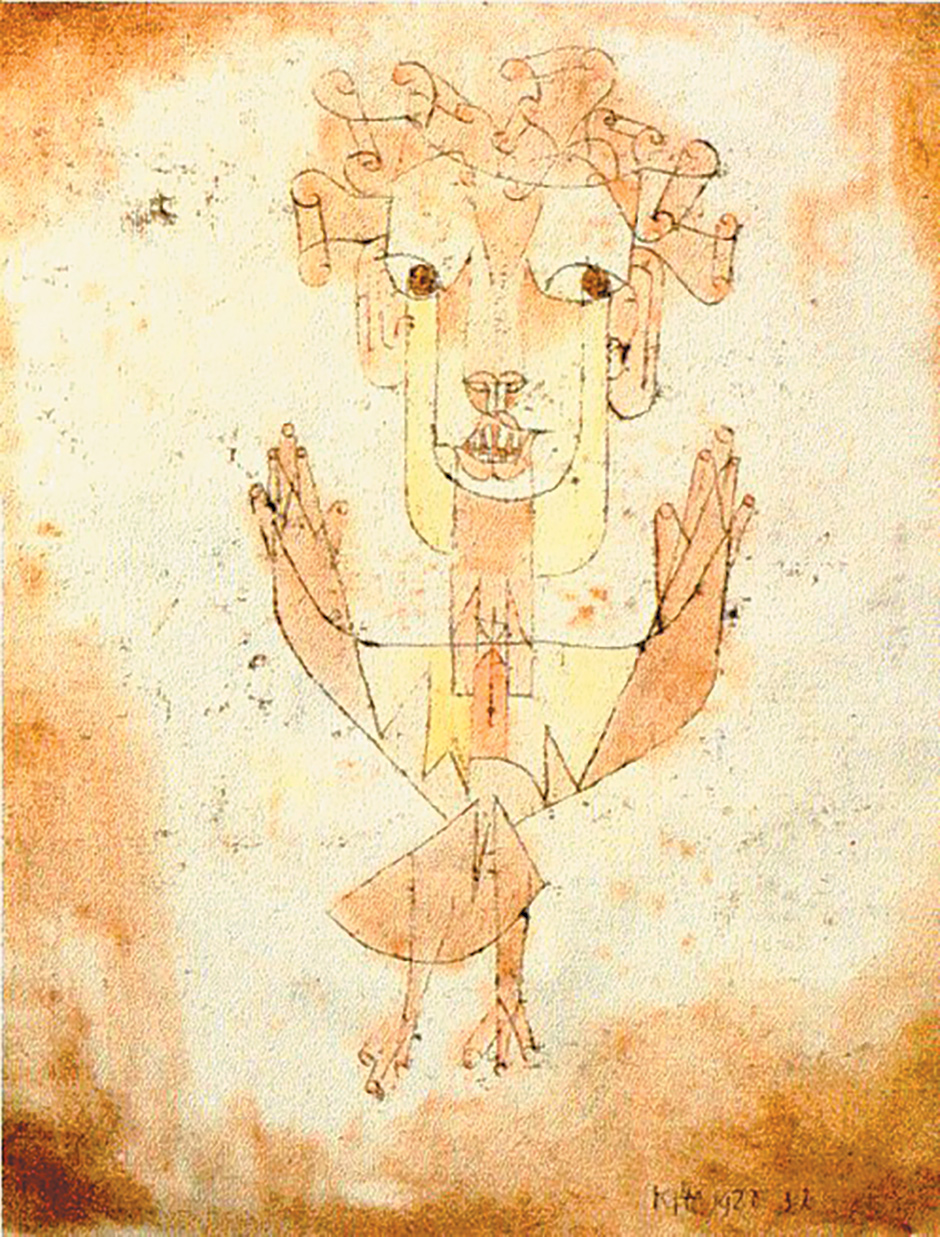

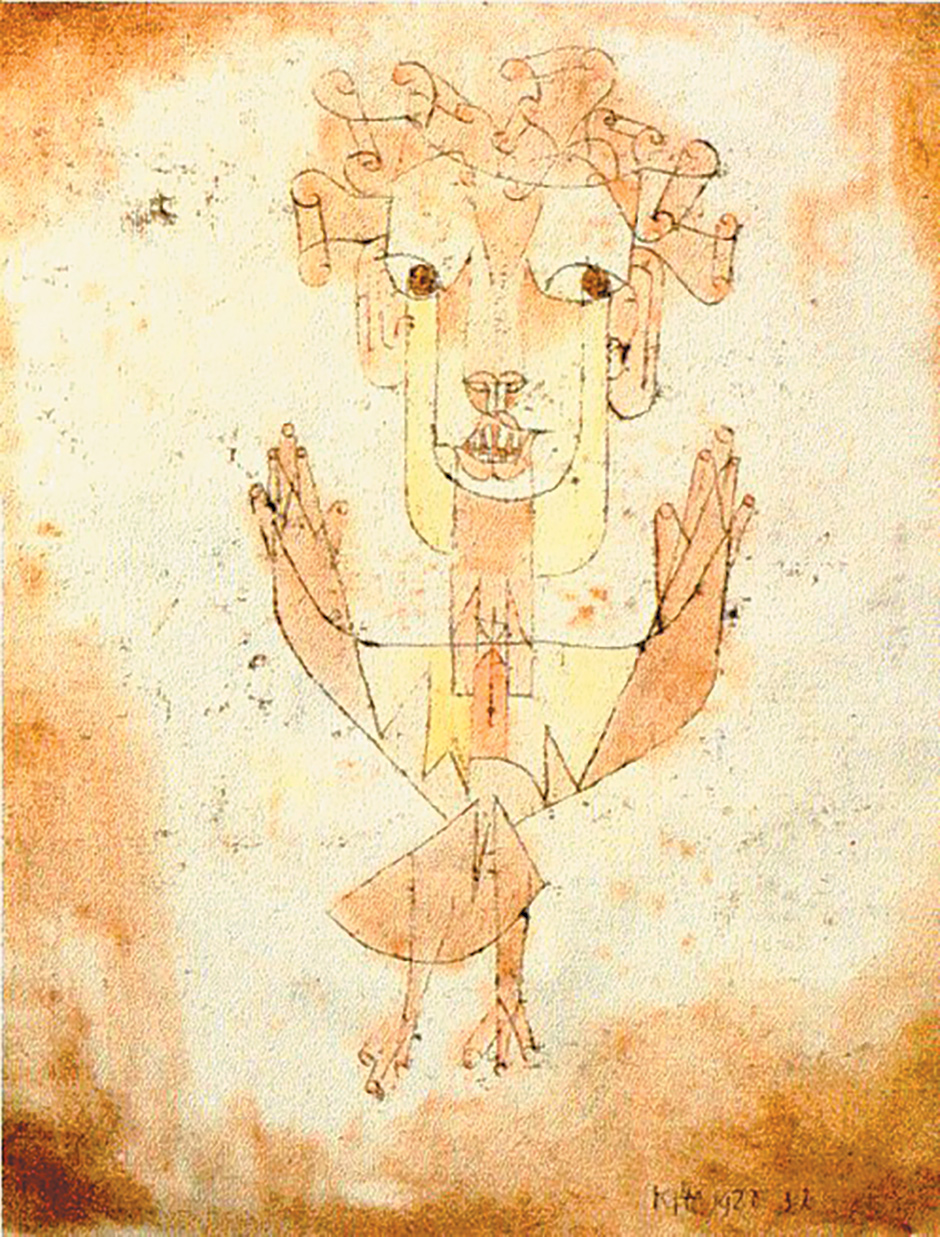

There is a picture by Klee called Angelus Novus. It shows an angel who seems about to move away from something he stares at. His eyes are wide, his mouth open, his wings are spread. This is how the angel of history must look. His face is turned toward the past. Where a chain of events appears before us, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it at his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise and has got caught in his wings; it is so strong that the angle can no longer close them. This storm drives him irresistibly into the future, to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows toward the sky. What we call progress is this storm.

— Walter Benjamin, “On the Concept of History,” 392 (italics in original)

Orientations allow us to take up space insofar as they take time. Even when orientations seem to be about which way we are facing in the present, they also point us toward the future. The hope of changing directions is always that we do not know where some paths may take us: risking departure from the straight and narrow, makes new futures possible, which might involve going astray, getting lost, or even becoming queer…

— Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others, 20-21

…

Uncertainties in global politics,

developments in artificial intelligence and cyberwarfare,

unprecedented scales of natural disasters,

a ticking clock on climate change,

and a new golden age in astronomy and extraterrestrial exploration

are what awaits us in the future.

…

But the future is happening now[tick]now[tock]now[tick]now[tock]. The future escapes.

…

Is the future inevitable? Is the future pre-determined?

To orient oneself towards the future…

does one turn to histories and genealogies and search in past paradigms?

For decades, “imagining alternative futures” seemed to be the conclusion de rigueur in much of cultural theory and in the arts. Perhaps stemming from and holding on to the radical possibilities of the 1960s, another world has been “possible” for at least two generations of artists and scholars. Even amidst these already radical possibilities, we, in the fields of theatre and performance studies, have considered ourselves particularly exceptional, not least of which is for the very fact that performance creates and presents alternatives — it is performative. The persistent consequence of performance theory was to suggest that we can indeed enact new possibilities and in doing so, we can change our world. But as we face what has been diagnosed as a series of crises in our lifeworlds, from climate change to forced migration to perpetual war, where does performance studies stand and can the field provide tools and concepts and performance to cope with the future, now?

We are reminded of Sara Ahmed’s dictum: “orientations are effects of what we tend toward, where the ‘toward’ marks a space and time that is almost, but not quite, available in the present” (Ahmed, “Orientations” 556). In this issue, we attempt to re-orientate what it means to think towards and about the future — a gesture that emerges from questions as to why there appears to be a vital urgency to study the future now. Building on a perceptible orientation towards collaborative knowledge in the arts and the humanities, we, the individuals and collective of the Future Advisory Board, orient ourselves as an experimental initiative of emerging scholars to the fields of theatre and performance, and envision our work as an opportunity for re-and dis-orientation. We come together from various parts of the world, connected by shared readings, artistic works, and disciplinary understandings. We meet virtually, digitally, on a cloud infrastructure to work through the processes of co-writing and co-editing. We are exploring a future of performance praxis and research that is intersectional, without a center and peripheries. We are just trying to keep it all together. Here, our first orientation is spatial, planetary. Future, here.

The idea of a “future now” also challenges the neat chronology of past-present-future. We refer to Antonio Gramsci’s concept of the times of the “interregnum,” especially as taken up separately by Zygmunt Bauman and Wolfgang Streeck where the old socio-legal-political order is dying but the new cannot be/is not yet born. Perhaps similarly, Lauren Berlant proposes the “impasse” as a term to describe the historical present, “a thick moment of ongoingness, a situation that can absorb many genres without having one itself” (200). To Berlant, the impasse is a space for transitions and adaptations, but without any assurances for the future. In contrast, Brian Massumi’s work on “pre-emption” and “pre-emptive time” captures the affective atmosphere of the shift towards a future time that is already pre-calculated and pre-controlled. Yet Achille Mbembe challenges these narratives of progress and linearity (as part of the imposed frame of Western rationality) by bringing back the complexities of studying “what it means to be a subject in contexts of instability and crisis” (17). Echoing these and other propositions, Future Now is situated in our moments’ contingency that call for re-orientations. Even if such a task is not new, we feel that interrogating the time and space of futurity is pressing. Future Now invites us to re-orient ourselves, not just eliding the present towards a future that is now, but also sustaining a plurality of physical orientations. Future? Here! Now! Then! There!

Here, now — as one possible departing point. Collective authorship and creation is perhaps an orientation towards intersectional praxis. We are committed to redefining performance studies in what Rosi Braidotti describes as “a process of redefining one’s sense of attachment and connection to a shared world, a territorial space: urban, social, psychic, ecological, planetary as it may be” (193). Collective editorship (here with eight people dispersed around the planet) happens with the implementation and negotiation of processes and protocols, ideas and ways of thinking, times, and spaces. Each one of us perceives and thinks about the future differently, and so the editorial enterprise of this issue means caring for the possibilities of the future for each other, as well as the contributors. This is a way of conducting research and of assembling knowledge that is in tension with the figure of the Romantic or even lonely editor or author, which has been a persistent and quintessential form of academic validation in humanities and artistic research (After Performance, “Transauthorship;” After Performance, “Vulnerability;” Cervera, et al.).

This voice, a temporal amalgamation of our single voices, wavers and pauses as it attempts to speak. And to speak in the singular. We are not altogether comfortable in taking this up. But we want to sit with this discomfort for a moment, to engage with the difficulty of engaging with the future and with the relationship with our field, together. We see this as necessary because the future is arriving now. In fact, every day. And yet we are reminded that we cannot afford to wait for it. And if we might be explicit, we are quite literally running out of future: according to the latest UN report about climate change, we are left with twelve years before a cataclysmic change in our atmosphere, our climate, our planet. This warning, however, also speaks to the contemporary challenges in engaging with the future, as it constructs an ontology of the future in crisis, a crisis that is already here and is here for all. Future now…

…

And now… And now…

…

In this vertiginous disorientation, caught in a present that is also the future, it is perhaps no surprise that we turn to Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History. The angel is stuck, facing the wreckage of the past, while being propelled into an unseen future. Immobilized in time, while also hurtling through it, the Angel is fixed with its back turned to the future. An orientation, Benjamin contends, forced by the storm of progress.

…

But what happens if the Angel turns around?

What if the Angel refuses to continue flying? Or its wings finally break?

What is stopping us from turning our heads, as it were, and attempting to re-orient ourselves?

How long can we continue hurtling towards a future perhaps even more disastrous than the wreckage in its wake?

We are not well-prepared for the future.

…

The struggles of the role of performance studies and theory in the “future now” return us to Jon McKenzie’s Perform or Else? (2001). His questions of how performance participates and is co-opted into machineries of management, capital, and progress are still as relevant as ever. Cultural and artistic fields are increasingly a decisive component in the value chain of almost every product of communication and experience, as artistic practices are understood to valuably contribute to the creative (and general) economy. Performativity and performance play a major role in the social practice of self-presentation and branding, the design and enactment of interactive and immersive experiences, and other methods of engineering sociality and community-building. Creative practitioners, makers, theorists, and artists become part of the process of production and circulation that form experiential nodes in the supply chain of daily life, tying in neatly with current and upcoming technologies — ubiquitous computing, augmented realities, nanotechnology, and cognitive science. With their expertise of performance, practitioners design theatrical and performative elements that strengthen user experience and enhance emotional reactions. Aesthetic production becomes integrated into commodity production, rather than disrupting perception towards a redistribution of the sensible for the purposes of criticality and dissensus (Ranciére 2010). From this perspective, aesthetic production is used to engineer affective politics and more efficient propaganda machines, echoing Walter Lippmann’s prophecies and Noam Chomsky and Edward S. Herman’s writing on manufacturing consent. As social movements in the street, in the theatre, or on the internet show sentiments of hope and resistance, we can also learn from José Muñoz’s insistence on a queer futurity that “may be extinguished but not yet discharged in its utopian potentiality” in the face of “here and now’s totalizing rendering of reality” (30).

…

But is that enough?

Is potentiality the theoretical vocabulary we need to think about the future critically?

Or has it become an instrument to manufacture futures, now?

…

You! You have potential for the future!

…

Is there escape from the cycle of production, from the supply chain?

…

Considering the institutional dimension of performance studies, we must also recognize the precarity of our own positions as faculty, as well as the precarious position of the university itself as a space for critical engagement. The forced closure of gender studies programs across Hungary, and the massive purge and detainment of academics in Turkey are signs of threats to the autonomy of universities and the constriction of academic freedom. Within academic institutions themselves, scholars are subjected to the ever-increasing scrutiny of performance review and performance standards, even as challenges and critiques of the status quo become the liminal-norm of academic performance itself.

…

I am an academic, I am a lecturer, I am a teacher, I am an artist, I am a project manager, I am a performer, a maker, I am a networking officer, I am a conference organizer, I am an event planner, and exhibition curator, I am a writer, I am an editor, I am a fundraiser, a strategist, a funding-bid writer, I am a development manager, and social media officer, I am a website designer, a hobbyist archivist, I am a content manager, I am a peer-reviewer, a second marker, a moderator, an external examiner, I am a supervisor, I am a learner, I am curious. I am a postdoctoral assistant, I design experiences, I am a teaching fellow, I am an ethnographer, I am a presenter, a distributor of knowledge, a Gantt-chart creator, I am a communications officer. I am a data analyst, I am a multi-tasker, I am a producer, I am a yes-person, I am researcher, I am a host, facilitating exchange, sharing of practice, I am a caterer, I am an invigilator, I am an evaluator, I am an impact reviewer, I am an imagineer, I am an experience evaluator…I am something else…I am

…

…

We need a future now…we are lagging behind…our vocabularies and ways are failing to describe and address…even the mundane and the everyday, in the meantime, in the now..

…

Indeed, what happens when the role of performance and performance theory are re-configured to aid the storm of progress and enact the here and now, as an accomplice to capitalistic accumulation of time and space? Performance Studies is responsive to the radically shifting intellectual and artistic movements of our time, and offers an analytical platform to disengage from hegemonic narratives. But we must recognize that performance may also function neatly in the consumer market by commodifying knowledge through its study, instead of serving via its regularly presumed role of disrupting social norms and dominant regimes.

Let us orient ourselves in time and space and on this digital document, and consider possible directions for navigating this issue. Orientations are bound together with directions, as Ahmed suggests, and directions are both defined as particular routes that are taken and as instructions that are given. Directions, she writes, “are instructions about ‘where,’ but they are also about ‘how’ and ‘what’: directions take us somewhere by the very requirement that we follow a line that is drawn in advance” (16). In bringing this edition of GPS together, the editorial team has drawn two connected but distinct lines that interweave longer research articles with shorter provocations. The first line is a more traditional collection of scholarly essays, notable for the time invested in them, the sustained duration of their engagement; labors invested with a particular (and familiar) type of academic and artistic rigor. Alongside this, we have also convened a forum of invited contributions (Future Now: A Forum) that seek lateral, personal, and even playful engagements with the future now. These two trajectories take on various lines of flight that lead us and direct us towards reflections on the future now from various situated perspectives and with various objects.

The future is dialogic. Two contributions in this issue use “letters” as a form of interaction with the now and the future. It is perhaps a fitting format, deriving from a nostalgic or even unsettled longing for an analogue form of communication that include or thinks through the lagtime of waiting for the post to arrive, sometime, somewhere in the future. The “Letters to (of) the Future” by the Department of Feminist Conversations contains a series of letters written as a dialogue with each other, to maybe whom it may concern and to the future. It is an act of collective imagination, and what they describe as an “anticipation and getting stuck in nowness; a now that is messy, throbbing, disorienting, and repetitious; a now that folds within it past and future.” In another “Letter to the Future,” performance artist and scholar, wen yau, poignantly asks how one could reach a future that seems constantly out of reach. She writes, “In the face of all the hostilities of our lives, what I can do is to entrust my imaginary and optimism to you, the unforeseen future.” Such attempts to reach out to the future may be framed within Lauren Berlant’s study on the affective present. In Berlant’s terms, the present is an “impasse shaped by crisis in which people find themselves developing skills for adjusting to newly proliferating pressures to scramble for mode of living on” (8). In such narratives we find people trying to adapt to ways of living, institutions, and work that offer the promise of “the good life.” Berlant questions whether such sentiments of optimism may be cruel, when the promise of a “good life” is forever delayed due to systemic inequalities that limit future possibilities.

The future travels in trains. In their entry to the forum section, “Standing on the Subway: Performance Exceptionalism and the Future of Public Space,” Stephanie A. Jones takes up subway performance and the space that shapes it, asking how the daily ways we are called to perform reinforce and reinscribe the regime of racial capitalism. Beginning with recent subway car redesigns, Jones examines the systems of surveillance and policing that are built into the very infrastructure of the city and daily life. The entry asks us to consider and reconsider those daily performances that must be performed as part of living in the city. The future is not foreclosed, but through Jones’ intervention, we see the impact of even seemingly mundane innovations and what might need to be done and undone in order to keep moving forward, both in the city and towards a more just future.

Yet, the future also walks around. In the article, “Pedestrian Provocations: Manifesting an Accessible Future,” we accompany Blake Morris and Morag Rose in a series of correspondence and walking exchanges where they invite us to embody how walking manifests the future. The correspondence is structured through a series of co-authored walking provocations — scores that become a generative mode of praxis shuffling between ideas of access and the materiality of actual conditions. The walkers stumble through the act of outing, in queerness and in disability, where “the invisibility of disability (both in a person and in infrastructure) requires constant outing accompanied by asking (for help, accommodation, access et cetera).” The future is accessed through its infrastructures, and walking offers a blueprint that is built with each step. As Rose reminds us, “[W]e have to deal with the actual conditions needed to manifest the city of our dreams.” These scores extend an open invitation to a walk that generates future walks; to walk with, rather than for.

The future is embodied. Donia Mounsef’s article, “The Future Performative: Staging the Body as Failure of the Archive,” explores embodiment and presence in terms of futurity, aiming to look at how performance constructs the future by destroying the material possibility of archiving the past. By examining the works of Québécois performance artist Marie Brassard, Iraqi-American performance artist Wafaa Bilal, and Lebanese performance artist Rabih Mroué, Mounsef asks the reader to “rethink the modalities of our perception bearing witness not to the construction of the archive but the spectacle of its destruction.” In doing so, Mounsef advocates for a more productive discussion of presence and futurity, moving away from the live/not-live dichotomy. Similarly, in the forum entry, “Looking Back and Look Forward in Dêgèsbé,” Soo Ryon Yoon examines the work of Koulé Kan, a Burkinabé-Korean dance company. Based in Seoul, the company performed Dêgèsbé in 2016, which opens particular questions and ideas about the past and the future. Yoon closely considers the ninety-minute dance piece as a “meditation on our sense of past, present, and future,” especially in light of the dancers’ personal histories and ongoing work in Korea. The entry examines the ways that bodies manifest past labor and “origins” as it sees a future performed and reconsidered in the work of the company.

The future is in its name. Situating her work in the anticipation of climate change, Vivian Appler sees this in connection with the conquest of outer space. In “Titan’s ‘Goodbye Kiss’: Legacy Rockets and the Conquest of Space,” Appler revises the historical background of some of the names attributed to celestial bodies within our solar system. Appler contends that “Although one could argue that astronomical knowledge has become more of an internationally collaborative practice now, thanks, in part, to the efforts of large-scale institutions such as the International Astronomical Union (IAU), there remain inconsistencies when it comes to living up to the multicultural aims expressed in its rules and active participation of diverse delegates within its working groups.” In highlighting this, Appler’s arguments tends towards the possibilities of decolonising planetary nomenclature in hopes of shifting the performativity of knowledge in fields such as astronomy and astronautics, which have been typical depositories of twentieth century futurology. Oscar Tantoco Serquiña’s review of Leo Cabranes-Grant’s From Scenarios to Networks: Performing the Intercultural in Colonial Mexico identifies Cabranes’ methodological contributions as similar to Appler’s, inasmuch as the book brings together two theoretical languages that have had great impact in recent performance theory: Diana Taylor’s “scenarios” and Bruno Latour’s actor-network theory with the mission of tracing the ways in which objects and behaviours become extensive and networked performances.

In “Staging the Right of Return: Moving Beyond the Now,” his personal autobiographical account of his family waiting to return as Palestinian refugees “for over 70 years,” Rand Hazou reflects on his performance Home is Where the Heart Is, and the tensions between waiting for the future, while perpetually moving into it. While Hazou takes up stones, keys and the Kuffiyeh as symbols of the Palestinian struggle, Alvin Tran uses objects to crystallize the passing of time in “Notes on an Impossible Space.” Through the materiality of the hourglass and the incense clock that accompanied trans-oceanic journeys and exchanges between the US and the Philippines, Tran reflects on the composition of time through song and sand. Kareem Khubchandani’s review of After the Party: A Manifesto for Queer of Color Life by Joshua Chambers-Letson emphasizes the temporality that informs the book, and highlights the political potential that Chambers-Letson carves out from finding performance theory after the party in which Jose Esteban Muñoz’s death was celebrated, but also after the legacies of the party, understood in a political sense, and in the context of minoritarian rights in the US.

The Future is a nation’s monster. Godwin Koay’s piece, “Dead Heritage: Living by Their Time,” interrogates the hegemony of time that is organised in the discourse around (national) heritage, asking what temporality has life been enclosed in, and specifically whose temporality. In tracing the rhetoric of legitimacy in authentic lineage and in legitimate belonging, Koay unpacks the “latent anxiety about identity which informs how the past is approached as a means to shape the future.” Instead of depending on palliative solutions that seek “some return to normality,” Koay calls for other realignments of organization, affinity and imagination that might emancipate other times, and other worlds. In “Imagined Beings of a Nation,” Marcus Yee makes a wilder case for the future of nationhood as experiments with hyperstition in conjuring a monstrous menagerie of our times. From the Global Soul to the Young-Girl/Toyol, from the Smart Creatures to the gedembai, these monsters manifest the epistemic margins of a nation, and Yee is a cunning guide who initiates us into the folklore of the future now.

The future is its media. Augé also alerts us that contemporary technologies “promote an ideology of the present, an ideology of the future now, which in turn paralyzes all thought about the future” (Augé 3). Media scholars such as Richard Grusin argue that media premediate the future, and play an important role in shaping our experience of time. Grusin imagines the future in two ways, “one which operates on a model of prediction, which imagines the future as settled (or to-be-settled), as moving from possible to definite, and another which imagines the future as immanent in the present, as consisting of potentialities that impact or affect the present whether or not they ever come about” (8). Contributions in this issue also touch on the role of media in the exploration of the “future now.” In Will Lewis’ article, “The Media Affects of Political Performance: Unmasking the Real and the Now,” he reflects on the cycles of social unrest and accounts for the availability of digital technology to mediatize and bring such protest events into the present. Lewis sets out to bridge notions of mediatization both in the present and the past, while considering the ways that such technologies and aesthetics perform the future. To do so, he examines two apparently distinct timeframes from a U.S. perspective, the 1960s, a decade imbued with revolutionary and radical politics, and the now, which spans the Arab Spring, Occupy Wall Street, and other recent protest movements. Also in this issue, Kornélia Deres, writing from the location of post-Soviet Hungary, turns to intermedial theatre and explores the potential of media in expanding the experience of temporalities, to both engage with the inescapable histories of state socialism, and reflect on possible future in “Performing (the) Future in Central Europe: In-between Media and Times.” In Immediacy and the Senses, Paul Geary’s voice, “a digitalized echo of a live act of performance” questions “immediacy” and how it has been thought as fundamental to our understanding of performance. Geary asks his listeners to actively participate in this provocation that challenges existing notions of immediacy, considering how the future of performance might require a different approach

The Future is staged. Theatre too appears in this issue as a future-making machine — if only one in which enacting possibilities may still retain political potency in the face of neo-fascisms reawakening across the North-Atlantic. In “Filling the ‘whole-hole’ of History: (rest)ing in Suzan-Lori Park’s Interregnum,” Jodi Van Der Horn-Gibson examines the theatre of Suzan-Lori Parks to think through the possibilities for “untelling the past.” The article develops a theory of performance that might find traction well outside the theatre as Gibson considers examples as different as Hamilton and Black Panther. In “A Forward-looking Theater,” Rita Valente-Quinn, who serves as Motus Theater’s Producing Director, questions how performance can shatter colonialist, fascist, and white supremacist tropes about race and class, and proposes that the future of performance lies in the pursuit of probing productive responses. Through Motus Theater’s recent works, which mobilize support for undocumented immigrants, Valente reminds us that performance can be forward-looking when it “increases awareness, shifts attitudes, and inspires action towards a more equitable and just community.” Conversely, in “Fever Dream,” Joel Tan contributes a play that dramatizes radical hope in the face of bleak futures, rendering sensible the deeply emotional and spiritual crisis that accompanies the end of the world.

…

To look forward, to look beyond, to look around, and to look anew–how do we find hope and possibility and remain optimistic beyond the exigency of the now? Projections of a besieged future have caught us (or some of us?) in a tautological loop, wound intensely within the boundary of the interregnum, caught in the lagtimes. Which orientations would take us (who?) into better futures?

…

In another dialogue included in this issue, science scholar Sorelle Henricus interviews philosopher and thinker of science Catherine Malabou in a dialogue titled “Tomorrow’s Imperative.” Henricus engages Malabou to think provocatively about the ways in which scientific thought and critical theory might engage with each other so as to consider knowledge more comprehensively. Is there a place for critical thought alongside and together with the sciences beyond a certain performativity of knowledge that occurs in both “philosophy” and “science” today? — Henricus asks, to which Malabou swiftly replies: “Clandestinity, diasporic spatiality, hiddenness, secrecy, have always been conditions of possibility for philosophical thinking […] Philosophy happens at the interstices of power and well established institutions. There is a dialectic to be found between public and private modalities philosophizing” (Malabou, in this issue).

…

“The concepts you are mentioning, epigenesis, plasticity, et cetera, clearly appear as interdisciplinary concepts, that show a very old and solid intricacy of science and philosophy. These concepts should be indicative of what should be developed in the future: a new collaboration between researchers from these different fields. Not, once again, for the sole beauty of the gesture, but on the contrary for the sake of efficacy in problem-solving processes.” (Malabou, in this issue)

…

The future is after-human. In “like a quantum of past future now,” mirko nikolić entangles performance in a quantum dance with capitalism, which in turn enacts performance in the logic of productivity, efficiency and output. Evacuating from capitalist futures, nikolić offers the diffractive conversations promised by quantum performance, enacting more-than-human kinships and reorienting how performance matters across scales of timespace. In contrast, in a recorded audio excerpt from her forthcoming play, “Not Now, Not Ever” (ideally transmitted on a wax cylinder), Lara Stevens stages in this issue the post-human maternal anxieties of a Spider Woman, and of her child’s future. In a companion text to the piece, “Climate Change Futures: What Can Performance do that Theory and Politics Can’t?”, Stevens points to the capacity for performance to embody abstractions, how it “lets us get down and dirty with the earth, lets us be material-girls without spending a dime.” In “Rambling with Robots: Creating Performance Futures with Online Chatbots,” Bella Poynton reflects about people set out to spend time with chatbots. While many people encounter talking robots on customer service calls or in automated ordering, she sets out to talk with chat bots daily and conversationally. In talking with the chatbots, Poynton saw glimpses of a cyborg future that feels striking like today as we perform for the bots, altering speech and syntax in order to more clearly communicate with the algorithm. Poynton’s forum entry opens questions of how we perform and for whom (or for what), especially in our day to day interactions with robots that generate language. Dwelling too on love and futurity, in “On Posthuman Love: Moving Beyond Affective Anthropocentrism” Haerin Shin focuses on recent film and TV productions that represent future imaginaries shaping and defining the contours of posthuman discourse, and questions what posthuman love would be, and in what form. Shin considers how the very act of envisioning affective engagement with or between mechanisms that lack biological constitutions — for example, AI software or humanoid machines — might be an attempt to reconfigure our notion of what human means and why it matters.

The future challenges us to act in the now. In his forum entry, “The Future is Now and it will Never Be The Future is Naked!”, Rumen Rachev playfully critiques performance studies and the artistic world’s infatuation with archiving and documentation, by framing these acts as forms of self-validation in the act of becoming a “professional performance research scholar.” Challenging the institutional demands to secure one’s future for career progression, Rachev thus returns to the McKenzian dictum of “perform, or else” and asks if any of these preparations even matter in the face of a possible apocalyptic future without humans. Future? Now?!

…

Do not get tired by the future. Take it one step at a time.

…

In closing, let us turn toward the “future now” one more time. As Ahmed writes, “if orientations point us to the future, to what we are moving toward, then they also keep open the possibility of changing directions and of finding other paths, perhaps those that do not clear a common ground, where we can respond with joy to what goes astray.” (Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology 178) Like Ahmed, Jussi Parikka invites readers to see the future in its operative sense, and that the future already has a bearing on the formation and enactment of the here and now. As always, a research trajectory fractures into “a thousand tiny futures” (Parikka), expanding into a myriad of questions rather than a set of fixed answers. The issue is a vortex; it contains multiple orientations that await for you in the future and in the now. It can be read traditionally as a compendium, but also as a companion–as a series of dialogues across time and space in which ideas and hopes interweave without necessarily inhabiting the same future. Our invitation is to connect and trace these and other orientations, to create moments in-between the several contributions in this issue–this editorial included.

…

The future–whether it is the future in general, or the future of Performance Studies–and the uncertainty it holds cannot be put down in a few words, pages, or volumes. “We might consider the utility of getting lost over finding our way, and so we should conjure a Benjaminian stroll or a situationist derive, an ambulatory journey through the unplanned, the unexpected, the improvised, and the surprising.” (Halberstam 16)

…

The future is the moment just past now…And now…And now…And now. In the spirit of the unpredictable nature of the future, of allowing for potentialities to emerge, and of moving against anticipatory regimes of future governance, we invite you to turn with us as we look around and, as Sean Metzger invites us in the Afterword to this issue, see “emerging scholars and junior artists as providing templates, or perhaps rehearsals, for the future.”

After Performance Working Group. “After Performance: On Transauthorship.” Performance Research, vol. 21, no. 5, 2016, pp. 35-36.

———. “Vulnerability and the Lonely Scholar.” Contemporary Theatre Review Interventions, vol. 27, no. 2, June 2017, https://contemporarytheatrereview.org/2017/vulnerability-and-the-lonely-scholar/. Accessed 17 January 2019.

Ahmed, Sara. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Durham, Duke University Press, 2006.

———. “Orientations: Towards a Queer Phenomenology.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, vol. 12, no. 4, 2006, pp. 543-574.

Augé, Marc. The Future. Translated by John Howe, Verso, 2015.

Bauman, Zygmunt. “Times of Interregnum.” Ethics and Global Politics, vol. 5, no. 1, 2012, pp. 49-56.

Benjamin, Walter. “On the Concept of History.” In: Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings, 4: 1938-1940, edited by Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, Harvard University Press, 2006, pp. 389-411.

Berlant, Lauren. Cruel Optimism. Duke University Press, 2011.

Braidotti, Rosi. The Posthuman. Polity Press, 2013.

Chomsky, Noam, and Edward S. Herman. Manufacturing Consent. The Political Economy of the Mass Media. Pantheon Books, 1988.

Cervera, Felipe, Shawn Chua, João Florêncio, Eero Laine, and Evelyn Wan. “Thicker States.” GPS: Global Performance Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.33303/gpsv1n1a8h

Gramsci, Antonio. ”Past and Present.” In Prison Notebooks Volume II, Notebook 3, 1930. Columbia University Press, 2011, pp. 32-33.

Grusin, Richard. Premediation: Affect and Mediality After 9/11. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

Halberstam, Jack. The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press, 2011.

Lippmann, Walter. Public Opinion. Free Press Paperbacks, 1997.

Massumi, Brian. “Potential Politics and the Primacy of Preemption.” Theory and Event, vol. 10, no. 2, 2007.

Mbembe, Achille. On the Postcolony. University of California Press, 2001.

McKenzie, Jon. Perform or Else. From Discipline to Performance. Routledge, 2001.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Cruising Utopia: the Then and There of Queer Futurity. New York University, 2009.

Parikka, Jussi. 2018. “Thousands of Tiny Futures.” 5 July 2018. https://jussiparikka.net/2018/07/05/thousands-of-tiny-futures/. Accessed 17 January 2019.

Ranciére, Jacques. Dissensus: On Politics and Aesthetics. Continuum, 2010.

Streeck, Wolfgang. “The Post‐Capitalist Interregnum: The Old System is Dying, but a New Social Order Cannot Yet Be Born.” Juncture, vol. 23, no. 2, 2016, pp. 68-77.