Madhuri Dixit

Pemraj Sarda College

Indian narrative traditions of poetry, dance, performance, painting, and sculpture have often used the ancient epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata as resources, finding them relevant from time to time.[1] The epics, with the distilled understandings of human situations as expressed by the content, similes, and allusions used therein, are usually explored by older performance traditions and new media alike, to overcome challenges of contemporary times. Just as Tamasha, the folk performance tradition of the Indian state of Maharashtra, has continued with the practice of showing in its opening piece the character of Krishna from Mahabharata, the new media of television has also showed both the epics in serialized form during 1980s.[2] In particular, the twentieth century theatres of India, belonging to various regions and languages, sought to comment reflectively on dilemmas and problems of modern life by taking up stories from Mahabharata. We find them in the well-appreciated and now cannonised plays like Andhayug (Blind Epoch, 1954) by Dharmavir Bharati; Yayati (1961) by Girish Karnad; Chakravyuh (Battle Formation, 1984) by Ratan Thiyyam; and Karnabharam (The Burden of Karna, 1984) by Kevalam Narayan Pannikkar.[3] In 1999, the play Yada Kadachit (If at All), written, directed and acted in by Santosh Pawar, joined these theatrical conversations with the epics, but adopted a very different approach.[4] He created a comedy based on various stories derived from both the epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata, and made it unique on two accounts. First, he reworked epical stories in a comic manner, unlike his predecessors in other Indian language theatres. The comedy parodies the epical stories through the employment of certain subversive tactics, which include: regional language, humour, procurements of elements from folk performance traditions, weird props, and movements of actors. Second, he achieved this feat through the use of excess as principle. He crowded the play with actions, words, characters, and references that quickly crisscross the past and the present with equal agility. The phenomenon of excess appears here as spillage that leaks several meanings. This multiplicity of meanings gives way to a subversion of established meanings; therefore, excess functions as a category of transgression in this case. Excess, as manifest in the play, could be positioned somewhere between expected compliance and potential transgression. With this logic, this essay intends to explore the specific theatrical devices that contribute to the comic nature of the play and catalyze excess in performance. It attempts to understand how currently relevant political meanings, including those that convey internal criticism of the regional Marathi theatre, are made possible in the performance.[5]

The question of meanings that get generated in the performance of Pawar’s comedy, Yada Kadachit, is important because “no telling [of an epic] is a mere retelling” as Attipat Krishnaswami Ramanujan claims (158).[6] Ramanujan’s study of multiple tellings [7] of Ramayana implies that retellings may have different endings, similes and allusions, and different intensity of focus on characters. These features introduce different themes at every point in a retelling, and render it a greater degree of independence as a separate work of art. Following Ramanujan’s observation, Yada Kadachit is observed to demonstrate such features and develop as a bizarre retelling of the Mahabharata story, while the features display a unique quality of being ways of excess.

Pawar’s entry point in the epic was a reflective key question regarding one of the teachings of Mahabharata, namely, “Truth always conquers in the end.”[8] Pawar wondered why it should be so. Is that a natural law, he asks, that some truth should emerge in the end, if at all it does? What about the suffering a person, a group, or a community necessarily undergoes till that point? (Pawar, personal interview). This is not a question that can be dismissed as a private philosophical query of Pawar because, according to him, the context for the question is a larger and representative experience that confronts an ordinary Indian citizen in his/her everyday life. It involves the seemingly inevitable, systemic impediments that obstruct a common person’s progress in life.

The Indian experience of underfunctioning public systems, including government departments, as well as the judiciary, has been (unfortunately) a representative and dismaying experience for many decades. The consequential historical helplessness of common people is well captured, for example, in the cartoons drawn by the celebrated Indian cartoonist, Rasipuram Krishnaswami Iyer Laxman (popularly known as R. K. Laxman). Laxman (1921-2015) created a cartoon figure known as the Common Man to represent the middle-aged, ordinary Indian male with a fine insight into the contradictions of Indian life.[9] The Common Man’s comments, filled with wry humor, render new insights apart from expressing helplessness in the face of oppression, delay, discomfort, and corruption in everyday public matters.

It appears that Pawar also has in his mind a similar conception of a layperson and his/her plight. It is in this context that the question of why the epic teaches us that suffering ends when some truth triumphs in the end, and not before, acquires a larger, graver, and socially representative dimension. It does so particularly when the question is put to the Indian state, with regard to its failure of delivering constitutional goals of equality, non-discrimination, justice, and fundamental rights, particularly in the case of weaker sections of the society. The timing of Pawar’s question– the late nineties –and his location as an ordinary resident of the cosmopolitan, but ghettoised city of Mumbai are more important since they render a further edge to the question.

For the Indian people, the nineties are characterized by some milestone sociopolitical developments that changed the earlier social power equations. They are: the implementation of Mandal Committee recommendations regarding reservation of enrollment in educational institutes and jobs in central government (1992); the opening of the Indian economy to liberalization (1991); the demolition of the Babari mosque (1992); the subsequent riots and bomb blasts in Mumbai with far-reaching consequences (1993); and the right-wing government coming to power in the state in that decade. Pawar comprehended the larger-than-life political paradox the nation has been undergoing since the nineties, which is apparent in every walk of life: everything receives the label of being done in the public interest, but nothing actually eases out the difficulties of a layman’s life. The continuation of farmers’ suicides in present times may serve as a bleak proof. He realised that, as citizens of one of the world’s largest democracies, Indians may be said to be politically powerful people but, in reality, they appear powerless as a community because electoral politics seems to benefit a few rather than the larger community. That way, the present era seems to be an era of false promises, deceit, and pretence. Such an age is called the Kaliyug in the scheme of Indian thought.

Musing on the Mahabharata story, Pawar wondered how some of the characters from Mahabharata would react to situations when put in similar circumstances, and under similar pressures, as that of the common person today. Stripped of their divine powers and royal grandeur, would they also get bogged down like the common person, by questions of “why me?”, “why now?”, or “why this?” If miraculously placed, somehow, in the present Kaliyug, would they behave in similar ways, or make the same decisions as they did in their own glorious and ancient times?[10] It is here that Pawar’s approach to the epic differs from that of his theatre predecessors. Rather than posing disturbing questions of our times and the epic stories as two separate entities, and then revisiting the epic for certain answers, as was done by several literati and theatre predecessors, Pawar brought down some Mahabharata characters to the present times and then showed them as bothered by the same questions that are confronted by ordinary Indians today. Since the lynchpin idea of this imaginative exercise was the condition of if at all such a thing happens, Pawar decided to name his play Yada Kadachit (If at All).

So what Pawar actually does in the play is to select some events and characters from the well-known Mahabharata story and experiment with them, while not disturbing the sequence of events related to the characters in the basic story. The tables are turned, either by replacing a character with another, totally unexpected character in a given situation, or otherwise, by depriving characters of their known actions, nature, or bearing, so that they behave in surprising ways in the play. The epic characters and their attitudes, decisions, strengths, and weaknesses are a part of common cultural knowledge on which the playwright could easily draw. For example, the character of Yudhisthir, the eldest among the Pandava brothers, is known to be a righteous person who upheld truth all the time at any cost. On the contrary, the character of Duryodhana, the eldest Kaurava, is known for his wickedness and greed. Such popular impressions of the characters are played with in the comedy. So, in Pawar’s retelling of the Mahabharata story, it is not Duryodhana who invites the Pandavas for the dice game with the intention of robbing them of their kingdom, but Draupadi, wife to the Pandava brothers, gives the call. Similarly, Krishna does not side with the Pandavas during the great Mahabharata war as is known to have happened, rather he aligns with the Kauravas in the play and motivates Duryodhana for war on the battlefield instead of Arjuna, the second Pandava.

For a conventionalist mind, such liberty taken with the story would amount to playing with the sanctity or purity of the text. Considering that Gita, the sacred book of Hindu religion, is a compendium of teachings of Krishna delivered on the battlefield in the war episode of Mahabharata, the liberty taken may as well be labeled as blasphemy or an insult to the religious sentiments. In this regard, the mainstream literate world always shows less generosity than the world of the folk in India. As Ramanujan points out in his study of Ramayana referred to above, folklore has always acknowledged and welcomed multiple tellings of a story. They may show gods being abused, or demons being revered as gods. Socially, these subversions symbolise a fictional record of diversified ways of the real, but with muted social resistances. For example, a folk story from the Maheshwari community of the Rajasthan region depicts a woman — a daughter in law — who scolds and abuses Ganesh (the elephant god) for becoming the news of the town. The stone idol of the god in the village temple suddenly becomes a matter of public curiosity because he suddenly changes his usual posture. He is seen with his finger put in his mouth, which is culturally a perceived gesture of astonishment. He does so because her action of roasting bread on funeral pyres surprises him. In another example, a version of Jain Ramayana considers Ravana (the demon villain in Ramayana) as a revered sage and narrates that Laxman (brother of Rama) went to hell for killing Ravana in the Ramayana war. Ravana’s case is interesting, because he is treated in distinctly different ways in the southern and northern parts of India. Ravana is generally not regarded as a villain in the southern part of India; on the contrary, he is venerated as a tapasvi (scholarly person). The northern part of India considers him to be the villain in Ramayana, one who abducted goddess Sita. He symbolizes evil, and therefore people in the north of India burn his effigies every year on the festive occasion of Dashahara. In the field of theatre performance, such extreme or greater liberties with texts wherein the orientation of character changes are rare examples, but folk performance traditions are more open about it. Making fun of the revered and god-like characters in the world of art by commenting on their actions, habits, and characteristics seems, in fact, a device of demystifying them, of tactfully making them more “approachable” and “common,” such as what happens in the Marathi folk performances of Tamasha and Dashavatar. Pawar understands this difference pertaining to tolerance and rigidity between mainstream theatre and folk performance traditions and, by choosing the style of folk performances to present his play, faces the risk of confronting cultural censorship.

Pawar’s contribution lies in applying a folk style of presentation that he borrows particularly from the Tamasha, Dashavatar, and Balya dance performance traditions[11] to the scripted play meant for the proscenium theatre. In theatrical terms, what he achieves is an exciting mix of rigorous physical energy, humor, and wit derived from the folkstyle that gets infused with well-orchestrated and well-scripted proscenium theatre practice. The main idea working in the comedy seems to be of exceeding various expected or normative limits: of words and their common meanings, actions and gestures, plot, and theatrical planning. As illustrated below, the excess is performed through repetition, substitution, going out of turn, and also through assemblage. Gestures and words are repeated, characters appear out of turn and out of place, their known orientations and nature change, the evil ones become the good ones, and so on and so forth. Such excess enhances the visual and auditory appeal of the play as a potpourri of additional characters, political punches, characteristic gestures that may linger in audience memories, dance movements, and popular songs made available to audiences.

Moreover, all these elements of presentation are performed with speed. Physical movements of actors, delivery of dialogues, the puns and allusions, the tempo with which songs are played — all come to the audience fast paced. It appears that only an alert and politically informed audience would be able to catch all the political nuances of what is shown and done on the stage. A good case in point is provided in the opening scene of the play that is performed in the style of Tamasha. Pendya, one of Krishna’s friends, is bothered and made fun of by three milkmaids. He starts praying that Krishna save him from the maids. He hurries Krishna’s entry by saying that Krishna should not waste time in wearing sandals, and he can come without donning them (anavani ye). The Marathi word “anavani,” used to denote barefootedness, is a pun on the name of the former president of the Bharatiya Janata Party, Mr. Lalkrishna Adavani, who also served one term as the chief of opposition in the parliament. In the same scene, the three maids introduce themselves as Samata, Mamta, and Jayalalitha. Two of the names, Mamta and Jayalalitha, are real names of women politicians while the third name, Samata, refers to the name of a political party. Jayalalitha was the Chief Minister and Mamata was a minister at the centre at the time of the opening of the play. With their hold on politics, people, and the government, they were appreciated and equally criticised for proving a match to their male counterparts in the state, and in the centre. Such references and their context, which need to be derived quickly from a single line in a dialogue, generate the possibility of reading the excess politically.

As another way of excess, the time period of the narrative story is overstepped by bringing in a few characters that are modeled on real, known, popular, contemporary or historical persons from different fields. Their range is far and wide. It includes popular film star Dev Anand (1923-2011), the dacoit and sandalwood smuggler Veerappan (1952-2004), and the great leader of struggle for Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi (1869-1948).The overstepping happens in the other direction, too, on the timeline, when some fictional characters belonging to an earlier epic, like Ravana, the demon villain, and Shravan, the obedient son from Ramayana, enter out of place in the play. These weird and funny additions fit in because they form intertextual connections between the ongoing story of the play and their original narrative stories. Connections are predominantly made by evoking common places (settings like King’s court or forest), and incidents/events (royals in exile or wedding of princess) that are previously known to the audience as belonging to other narrative stories. Thus, when the royal Kaurava parents (from Mahabharata) meet Shravan (from Ramayana) and Veerappan (the contemporary real dacoit) in the play, it has to be in the forest, because all of them visit and/or reside in the forest for some time in their separate, independent stories. Originally, the forest is a place of exile for the Pandava princes; but the matter is subverted in the play by sending the Kaurava parents to exile. In the Ramayana story, Shravan accidently gets killed in the forest while fetching water for his blind and thirsty parents. Similarly, the real dacoit, Veerappan, was a sandalwood smuggler who operated from and went into hiding in the dense Karnataka forests to escape from the police. Just as with the places, the intertextuality is observed in case of events, and it evokes the common cultural knowledge of the audience. The play shows Ravana enter the court where Draupadi’s Swayamvar (marriage by self-selection)[12] is taking place. He has clearly mistaken it to be the Swayamvar of Sita in the Ramayana story, in which he had failed the challenge of lifting the bow. In the play, he can lift it, but breaks it during the attempt. The Pandava and Kaurava princes present in the court rush to beat him for breaking the bow. After a little clamor in which a lot of political repartees are made, peace is established, and Ravana is finally shown to have aligned with the Kauravas. When setting or event is not useful, it is a special characteristic or an achievement of a real person that is drawn upon as the basis for intertextuality, as happens in case of Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi successfully made his insistence on Truth into one shining tool for the struggle for Indian independence. When Gandhi comes in as a character in the last scene of the play, he comes in as an exponent of truth who removes doubts of other characters, and puts their minds at rest.

Just as the oscillating timeline and continuous going back and forth in the past and the present breaches the basic story of Mahabharata in the play, a deliberate insertion of contemporary sociopolitical and cultural references in the mouths of epical/mythological characters further contravenes the story. Popular songs, lines of dialogue from Bollywood films, and jokes about the names of current and past politicians are randomly picked upon from the mixture of collective cultural memory to form a network of references within the play. Yet, it is true that the connections do not always hit the mark or happen to be meaningful, and, depending on the perspective, some of them may well appear as simply unnecessary. Nonetheless, the most important job that they perform, apart from increasing the comic quality of the play, is that they assist the process of subversion. Their pleasantly shocking quality helps takedown the epical/mythological characters from their pedestals in the collective cultural imagination. This is exactly the way in which the play shows affinity to folk performance traditions. A case in point is the surprising substitution of an answer by a Bollywood dance song. Through its shocking value, the idea topples down the veneration won by an important character in the basic story for displaying certain fine skill. Mahabharata tells us that Arjuna won appreciation of his master Drona for his unshakable concentration on the target, while learning archery as a prince of Hastinapur. The story, which is frequently found in Indian educational discourse, goes like this: Drona sets up a false parrot in a tree as the target for an archery exercise. He asks every student what they see there. It is only Arjuna who answers that he sees the eye of the parrot as the target. The audience is supposed to recall this story when the same question, “What do you see?” is put to Arjuna in the play. But this time, there is no Drona who asks the question, as the play is not telling the story of the young student princes and their master. Arjuna focuses not on the eye of the parrot in the play but on the eye of the rotating fish, set as challenge in the Swayamvara of Draupadi, and it is Yudhisthir, his elder brother, who asks him the question. The swayamvara episode is a different story that once again proves Arjuna’s skill as a fine archer. Arjuna is expected to say “dola,” which means “eye” in the Bankoti language used in the play. Instead, he bursts into singing the popular Bollywood dance song, “dola re dola” from the film Devdas (2002, Directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali). Both words are similarly pronounced, but the word in the song is a Hindi language word, and it means “something danced.” There is no play on the meaning, but only the fun of having similar pronunciation. At the most, the trick suggests everyone’s fascination for Bollywood beyond age and status.

The character of Draupadi, wife to the Pandava brothers, is renowned in Mahabharata for her determination and strength. Such is her fame that the Hindu religious way of life that describes certain rituals to be performed in the morning by every person recommends that Draupadi’s name be remembered ritually as one of the five famous daughters of ancient India. But in the play she is also demystified, and is made to look ordinary in a similar manner like that of Arjuna. In one scene, she is shown singing a popular erotic folk song (a lavani) that depicts a beloved’s wait for her lover. The song sounds inappropriate as she waits for her brother-in-law, Duryodhana. Though the inappropriateness of the song juts out, and it bereaves Draupadi’s character of the mythological grandeur, by suggesting a liaison between Draupadi and her brother-in-law it also takes a dig at the idealized value system of the normative family.

The insertion of contemporary sociopolitical references is not always meant for mere pleasure of laughter. Sometimes, as happens in case of the character of Karna, it pushes the audience into thinking about burning issues. Referring obliquely to the injustice met by Karnain the basic story of Mahabharata, the play suggests that the old social division of four varnas (the Chaturvarnya system) has given way to caste system. Karna remained a subordinate till the end of Mahabharata. He could not enjoy status and privileges due to a prince, as no one knew the shady reality of his birth as the eldest among the Pandavas till the war in the end. His birth status obstructs his right to contest in the Swayamvar. The play shows Draupadi asking for Karna’s identity card, an analogy for the present-day caste certificate that a subordinate caste person needs to produce everywhere to earn benefits of reservation. In a weird move in the play, he is handed over a real loudspeaker as his identity card, because the Bankoti word for loudspeaker is Karna, and the object supposedly represents him. The scene reflects how caste matters as identity in a negative way in electoral politics.

The deliberate choice of banal objects that would be used as stage property constitutes a unique feature of performance of Yada Kadachit, and it renders a different dimension to excess. It naturally shocks the audience a little to find what can best be called just a small replica of the full-fledged object they expect to find on the stage. Yet, it is through their trite appearance, which in fact conforms toothier comic elements in the play, that the objects convey the characteristic meaning of Kaliyug, namely dishonesty and disappointing pointlessness. This is evident in a scene towards the end of the play in which Krishna blows a conch to start the great Mahabharata war. The Mahabharata story narrates that Krishna blew his Devdatta conch to signal the beginning of the last devastating war. It is said that its deep resonating sound reached the three worlds, upon which gods in the heaven showered flowers on him. The scene looks all set in the play for the audience to hear big thundering sound of the conch, when there appears a toy conch that, at best, gives a bleat upon blowing. It resembles a toy pipe usually sold in Indian fairs which has a rolled, plastic tube fitted inside that unfolds on blowing to produce sound. Such a toy conch may well imply that war is a child’s foolish play.

Parody joins hands with banality in the play to bring out a hollowness assigned to the current times. A scene towards the end, which brings in Time as a voiceover, offers itself as a good example of how parody works in the play. The Time voiceover addresses actors on the stage, in a Brechtian way, to say that their time is up, even if they have performed well. For the Time voiceover, the scene borrows the image of Samay (Time) from the immensely popular televised serial on Mahabharata (telecast from 1988 to 1990 on the national channel). A big, slowly rotating wheel used to appear on the screen in the beginning, as well as in the end, of every episode. An outline of a sitting sage and a general pictorial presentation of a galaxy served as the backdrop for the wheel. The visual image was accompanied by an impressive male voiceover supposed to be that of Samay as the omnipresent personified narrator. None of the grandeur, as viewed in the televised image, is associated with what is found in the play. Rather, there is simultaneous evocation and disruption of the screen memory. A mundane looking, worn out, small tire of a two-wheeler is pushed on the stage from one of the wings to represent Samay.

This parody of the televised image cherished in public memory, in fact, speaks for the characteristics of present times in the context of a hurried urbane lifestyle. The grand scale of cosmic time breaks down to minutes and seconds, and functions as an oppressive force in ultra-modern lifestyles of urban people. The most populated city of Mumbai sees millions of people commute to and fro everyday to their workplaces. The city is known to be tied to the clock. Experiencing it well by being a resident of Mumbai, Pawar suggests that we have dwarfed and accelerated time, but to no avail.

In another example of parody that derives at the commonly found attitude to cheat others, Pawar plays a trick with household objects of everyday use. Mass produced objects like bottles, containers, kitchen and garden tools, or even eatables like candies, come in various sizes, shapes, textures, or colours, and take up a special place in individual memory because of their sustained use. Boxes may come in the shape of animals or candies can have the shape of flowers. It is possible that we remember these objects before we remember the actual things to which their features resemble. For example, the fish-on-a-rope soap was a household entity a few years before hand-wash bottles replaced them on the household washbasins.[13] As such, the audience is likely to imagine the fish soap if told that a fish was used as a target for a show of archery. In the Mahabharata story, the challenge set for Draupadi’s swayamvar was to shoot the eye of a real fish rotating in the air. But the suitor-archer was not allowed to look at the real fish; instead, he was to see the reflection of fish in the water pot below, and aim at its eye. In the play, the fish is replaced by a fish-on-a-rope soap.

The smart character of Arjuna takes the fish soap in his hand to pierce its eye with an arrow instead of shooting the arrow in the air. The soap, by nature a slippery object, slips from his hand twice, and plunges into the water below. The comedy is enhanced by the sound of it slipping into the water. The audience may well think that it suits the spirit of Kali yug, that the fish has a false appearance as a soap bar, and that Arjuna cheats to win. The cheating provides an illustration of the main idea of the play, which is to see how the Mahabharata characters would behave, if at all they were to reappear in the present age.

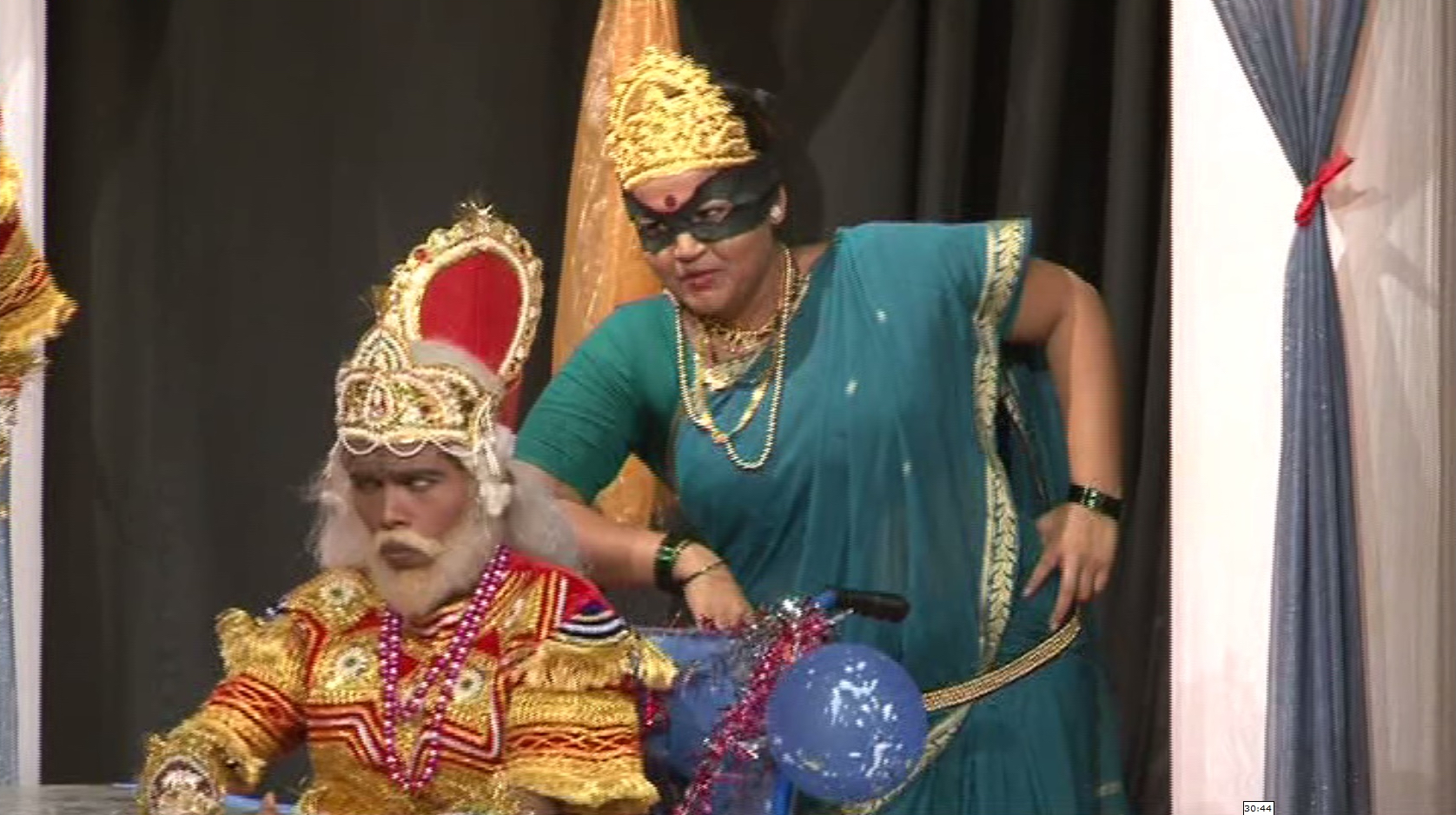

Objects used as props not only reduce the temporal distance between the epic and the contemporary period, they also cut down on the spatial dimensions. Gandhari, the mother of the Kauravas, is said to have borne self-inflected blindness throughout her life as a gesture of protest for unknowingly been married to a blind king, Dhrutarashtra. She is said to have tied a strip of cloth on her eyes for all her life: an action of self-sacrifice that won her a moral authority. In Pawar’s scheme of imagination, Gandhari will obviously never surrender to such an idea, and let go of her visual pleasures. A strip is surely tied on her eyes in the play, but it is more of a mask like that of Batman, the fictional superhero in American comic books, through which she can see everything.

The superimposition of meanings enabled by the particular kind of mask may cause a plethora of interpretations. We may ask if she is made into a comic character, like that of Batman. We may inquire if she refuses to be the real Gandhari by defying the original authorial decision to tie a strip of cloth around her eyes. Or, we may think that she is a very individualistic person, and may be an aware feminist who does not let her space be violated by refusing the blindness imposed on her. With the ability to see, Gandhari not only steps out of the original Mahabharata story but enters the space of Ramayana to momentarily take up the role of Sita where her “see-through mask” pays her the reward. She sees the golden deer in the forest that Sita is made to see in the Ramayana story. But there would be no Ravana coming to abduct Sita in the play; on the contrary, Gandhari-turned-Sita meets the dacoit and sandalwood smuggler, Veerappan, who dwells in the forest.

Bankoti as the language of the play was an unusual directorial choice (Pawar and many actors from the original team speak the language), and in the performance, it turns out to be yet another important tool of subversion. It subverts a fact that the modern Marathi theatre has historically cherished namely that, for social recognition and for the sake of quality, the standard variety of the Marathi language should always be preferred in the theatre. Bankoti is one of the languages spoken (particularly in and around Ratnagiri district) in the coastal belt called Konkan, and is intelligible to the Marathi speakers to some extent.[14] Nonetheless, it is the language of subaltern people, if the larger picture of regional development is considered; because historically the Konkani people have been cheated by the politicians who have been idiomatically stating that they would make California out of Konkan. Its noteworthy sociolinguistic characteristics happen to be its cynicism and ease of creating humour, and it would not be off the mark to say that in this, the language mirrors its people. An average portrayal of a Konkani person in any genre would show him to be quarrelsome, passionate even about his iota of land, poor in resources, always looking up to the city of Mumbai for earning a better livelihood, a little disrespectful of others, and possessing a strong sense of wry humour. Could we think that the language of such people, and the attitude it projects, would be budged even slightly, by the sophistication, artificial awe, and heavy philosophical import of the epics? It is obvious that Bankoti does not possess the sheen as that of the standard, drawing-room variety of Marathi language that is historically adopted by Marathi theatre. On the contrary, Bankoti is identifiable for its slightly uncouth expression and highly inflected pronunciation. But it is spoken by a sizable number of people, not only in the region of its origin (Konkan, the coastal belt) but also in the city of Mumbai. This is where they have been migrating historically for the last century and a half, and where they are known for their love of theatre. With its spirit of half-humorous cynicism, the Bankoti language successfully renders a regional attribute to the play, and roots the epic characters in Konkan.

The subversive potential of humour is chiefly enabled by the hybrid mixture of folk forms in the play that the director has not hesitated to experiment with. It looks like a willful selection of elements from several folk theatre and dance forms, like the Namannatya, Tamasha, and the particular dance form of the Balya community. The fusion of folk elements is visible mainly in songs, movements, and addresses to one another, and in the creation of particular mannerisms and the appearances of characters. For instance, the character of Krishna enters twice in the play. His first entry is required by the folk style borrowed from Tamasha, and the second entry is a requirement of the story itself. All the characters keep on dancing or making dance-like movements all the time, so much so that no static moment appears in the play. These excessive movements, in addition to some of the actual dances they perform on the stage, are taken from the Balya dance form. Characters dance when they enter or exit or introduce themselves to the audience, but beyond that they also dance to show agitation or gladness. The rigorous dancing movements are demanding from the perspective of performance, since they involve a high level of energy on part of the actors. Nonetheless, they render a totally fresh, farcical, and very energetic outlook to the comedy.

For all the above-mentioned aspects of the play, it is possible to state that the play offers internal criticism of the mainstream Marathi theatre. Some of the subversive meanings it generates expose weaknesses and the areas of dominance of the Marathi theatre. This should not imply that the comparison stands only between a monolithic Marathi theatre and Pawar’s play. Indeed, there exist different theatres in the Marathi-speaking region that employ particular styles or folk forms; have their own loyal audiences and spaces of performance; and are popular.[15] Nevertheless, Yada Kadachit stands out for the said comparison because it experiments with the form and presentation, faces controversies and cultural censorship, and yet achieves spectacular success. By providing an opportunity to the theatre minority to show their art, Yada Kadachit democratized the Marathi theatre in its recent history.

It would not be farfetched to say that, as an event, the production of Yada Kadachit changed the balance of power in the regional theatre world, since it happened to challenge the dominance of the upper-middle-class and caste in the local theatre practice. Broadly speaking, Marathi theatre is generally identified with drawing room drama that adores sophisticated language, stories with clichéd messages, box sets, and usually displays an upper class and/or upper caste character. The success of Yada Kadachit is significant because its brilliant yet weird-looking fusion of styles and content did not even try to cater to the regular linguistic and visual pleasures extended by the Marathi theatre. That it asked for a theatrically unconventional taste of appreciation is clear in the early discouraging response of the regular theatregoers, consisting of upper- and middle-class and upper caste members. They did not find anything in Yada Kadachit apart from the appalling physical energy because many in the class entertain different ideas of life, morality, and entertainment.

The said democratization does not merely imply a pastiche of elements taken from distinctive styles and genres. On the contrary, it happens on several levels. The performance brought in new skills of acting as well as new actors, and defined acting in a new way. It diversified the profile of the theatre audience in terms of caste and class. It successfully demonstrated that a minority language can become the language of the Marathi theatre. Most importantly, the play dared to question so many culturally given things by adopting a fresh, comic approach to epical stories. A similar attempt looks unimaginable today, since the grip of fundamentalist right-wing cultural politics has tightened further.[16]

The play did suffer from a criticising and violent response from a group of people, the cultural police, who came to notice it for wrong reasons. With the rise of the polarization of politics during the nineties on the basis of religious fundamentalism, Indian society has borne the brunt of cultural policing in varied forms. Seeking their own social and political visibility during that time, they forwarded the now familiar reason of their feelings being hurt by what they perceived to be disrespect to deities in the play. They pressured Pawar to change the names of some of the characters so that they could not be easily identified with the respectful characters from Mahabharata. They also asked him to delete some politically meaningful references in the play. They disturbed some of the shows by raising slogans during the performances and by threatening the actors. The actors became so very conscious during one of the shows that they feared disturbance, even if someone got up to pee (Pawar, personal interview). They extended their objections to another of Pawar’s plays called Amhi Pachpute (2008), a political satire of the then hot topic of locals versus outsiders, and exploded a small bomb during one of its shows.[17] But since people did not stop flocking to Yada Kadachit performances, the play went on with its stormy history of production to complete around 4500 shows to date. Pawar states that, if renowned members of the theatre community would have refuted the cultural-political charges against the play at that point of time, it would have prevented the nuisance of cultural policing that now has blown out of proportion.

The cultural counter-politics of the play can be read in its minute gestures, in the bringing together of references in their cultural meanings, and in the linguistic and tonal inflections of speech. The norms of theatrical language, acting, content, and audience pleasure are transgressed with the consequence of evoking cultural censorship. Excess is the name given here to the logic of cohabitation of the seemingly inharmonious elements that overflow in the play. Openness towards diversity, in theatrical terms, could be the precondition to enjoy such a combination: something that neither the cultural police nor the established theatre practitioner and the sophisticated audience could manage to have. It is a telling fact that the play received abundant popularity but not theatrical accolades in equal measures. It did not do the rounds of theatre festivals. Nevertheless, the intended excess successfully leaks several meanings that question the social and cultural balance of power and shows a fresh way of subversion through laughter.

I would like to thank Santosh Pawar (Director,Yada Kadachit), for giving a detailed interview about the process of Yada Kadachit. I thank Dr. Pravin Bhole (Director, Centre for Performing Arts, SPPU) for generously providing the images of the student production of the play. Thanks are also due to Rohan Chinchore, Library Assistant (CPA, SPPU), Amol Patil and Ajit Sabale PhD students (CPA, SPPU) for all their help and time. The seed version of this article was presented at the Performance Studies International Conference, 2017.

[1] The ancient epic of Mahabharata narrates the story of war between rival cousins, the hundred Kaurava brothers and the five Pandava brothers, for the throne of Hastinapur. The Kauravas decline to give the Pandavas their share of the kingdom. Losing everything in the game of dice and crassly insulted by the Kauravas’ unsuccessful attempt to strip their wife Draupadi in the court, the Pandava brothers call a devastating war on the Kauravas. With the help of Krishna, the Pandavaswin the war after much suffering and loss. The epic today seems a family of texts, according to A. K. Ramanujan (2004), as it incorporates several stories, diverse interpretations, and multiple levels, and no text can be connoted as the original text of Mahabharata. It may be alternately understood either as a story of human relationships, or a story of the conceptual understanding of one’s duties and moralities, or, on a social level, it may seem to document conflicts and collaborations among different coexisting societies over resources.

[2] The witty, unscripted repartees in Tamasha, enjoyable for fresh sociopolitical comments, begin from the opening scene, in which lord Krishna and his friends stop the maids on their route to market because they want to loot the milk and butter the maids carry for selling in the market.

[3] In addition to these Indian playwrights and directors, Peter Brook, the English theatre and film director also took interest in Mahaharata and produced his play, The Mahabharata, in 1985.

[4] The link for the video of the play is: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kNAnZL0czs0&lc=z12nurrr4wyrvtzna234zpsoglnrwfnxq04. Accessed 11 June 2018.

[5] The nomenclature “Marathi Theatre” is used to denote the modern proscenium theatre in the Marathi language that began as a colonial practice in the nineteenth century. It is not exactly a monolithic entity. For an outsider, various proscenium theatre practices in the Marathi speaking region that do not gel with the mainstream practice in terms of language or presentation, including the parallel theatre or the Dalit theatre, can be clubbed under the name for the sake of simplified understanding. However, for an insider, the term usually means mainstream commercial theatre performed in the standard Marathi language.

[6] Attipat Krishnaswami Ramanujan(1929-1993) was an Indian poet and William E. Colvin professor in the Department of South Asian Languages and Civilizations at the University of Chicago. Inclusion of the essay “Three Hundred Ramayanas…” in Delhi University curriculum was challenged in the courts in 2008 on the basis of the objection that only teachers with Hindu background can do justice with the essay. The objection was dismissed by the court. Ramanujan’s query was to find out how the hundreds of tellings that come from different cultures, languages, and religious traditions relate to one another, and “what gets translated, transplanted, transposed” (134) in the process. Though “the weave, the texture, the colours are very different” (143), observed Ramanujan, the endings and beginnings do not simply differ in each telling but “with each ending [and beginning], different effects of the story are highlighted, and the whole telling alters its poetic stance” (151). Similarly, there are varieties of themes introduced through similes and allusions at every point, and through the intensity of focus received by a character. In these ways, the several tellings together make a family of texts where “no telling is a mere retelling” (158).

[7] Ramanujan insists on using the term “telling” rather than other frequently used terms, like version, because he wants to negate the possibility of an original or a Ur-text present in case of Ramayana, as usage of the other terms might indicate (134).

[8] A similar adage “Satyamev Jayate” (only Truth triumphs) is the national motto of India and is scripted below the Indian national emblem. It originally appears in the ancient text Mundak Upnishad.

[9] For more information and analysis of Laxman’s achievements, see the link http://www.cambridgeblog.org/2016/01/the-times-of-r-k-laxman-acche-din-good-days/

[10] Going by the cyclic concept of Time in the scheme of Indian thought, each yug (cycle or age) has specific characteristics. The present yug is called Kali yug and is characterized to be an age of increasingly non-meritorious behavior.

[11] Dashavatar (ten reincarnations of Lord Vishnu) is an impromptu form of theatre originating from the Konkan region and performed by non-commercial male artists mostly during festival days. Balyais a community dance from the same region and is performed by men, many of whom work as househelp in the city of Mumbai. Balya is a term for a ring ornament worn in the ear by these men.

[12] Swayamvar implies willful selection of a groom by a princess. It is supposed to be a competitive event for prospective grooms who have to prove their worth by completing a challenge set by the father or the brother of the bride.

[13] For an image of the fish-on-a-rope, see https://giovannidcunha.wordpress.com/2011/05/31/fish-on-a-rope/

[14] Konkani language was listed as a national language in the Eighth Schedule of the Constitution of India in 1992. The preceding debate is of special interest because “it illustrates with unusual clarity the perennial problem of deciding what constitutes a separate language” (Fergusson qtd. in Huebner 62).

[15] For instance, the Kamgar Rangbhumi (theatre of labours), Zadipattirangbhumi (a local theatre genre in the north eastern side of the state), the experimental theatre etc. See Sathe “A Socio-political History of Marathi Theatre”(2015); and Gokhale “Mapping Marathi Theatre” (2008) for an introduction to the gamut of different theatres, loosely termed as Marathi theatre.

[16] Two recent examples can be cited as evidence. A cultural group named as Karani Sena protested violently against the recently released feature film, Padmavat (2018, Directed by Sanjay Leela Bhansali). Objecting to the portrayal of the historical character of queen Padmavati in the film, they pushed the director to change the name of the film from “Padmavati” (the queen’s real name) to “Padmavat” (title of a long medieval verse poem by Malik Muhammad Jayasi). It was obvious from the course of their protest and the resultant compromise that, rather than insisting that cultural accuracy be regarded, it is the excessive pride and caste/community identity that plays a role in exercises of cultural censorship. The second example can be cited as the changed ways of addressing historical leaders/gods. In place of customary singular nouns/pronouns, it is insisted that plural nouns/pronouns be used to show respect to them, however ungrammatical it may sound. Media reporting is a ready site to spot how these trends have emerged.

[17] Two of news articles that reported the incident are:

“Bomb Blast Rocks Thane Auditorium.” Mumbai Mirror. 5 June 2008. https://mumbaimirror.indiatimes.com/mumbai/other//articleshow/15817392.cms. Accessed 11 June 2018.

and,

“One Marathi Play, Two Bombs, Seven Injured: Cops Search for Script.” Indian Express. 5 June 2008. http://archive.indianexpress.com/news/one-marathi-play-two-bombs-seven-injured-cops-search-for-script/318845/. Accessed 11 June 2018.

Gokhale, Shanta. Playwright at the Centre: Marathi Drama from 1843 to the Present. Seagull Books, 2000.

———. “Mapping Marathi Theatre”. Seminar: Talking Theatre.588, 2008 (August) http://www.india-seminar.com/2008/588/588_shanta_gokhale.htm. Accessed 13 June 2018.

Sathe, Makrand. A Socio-political History of Marathi Theatre: Thirty Nights. Oxford University Press, 2015.

Ramanujan, Attipat Krishnaswami. “Three Hundred Ramayaṇas: Five Examples and Three Thoughts on Translation.” The Collected Essays of A. K. Ramanujan. Edited by Vinay Dharwadkar. Oxford University Press, 2004.

Huebner, Thom. (Editor.) Sociolinguistic Perspectives: Papers on Language in Society, 1959-1994. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Pawar, Santosh. Personal Interview. Mumbai. 4 May 2017.