Plantón Móvil: Interspecies Collaboration in the Walking Forest

Lucia Monge

Rhode Island School of Design and Brown University

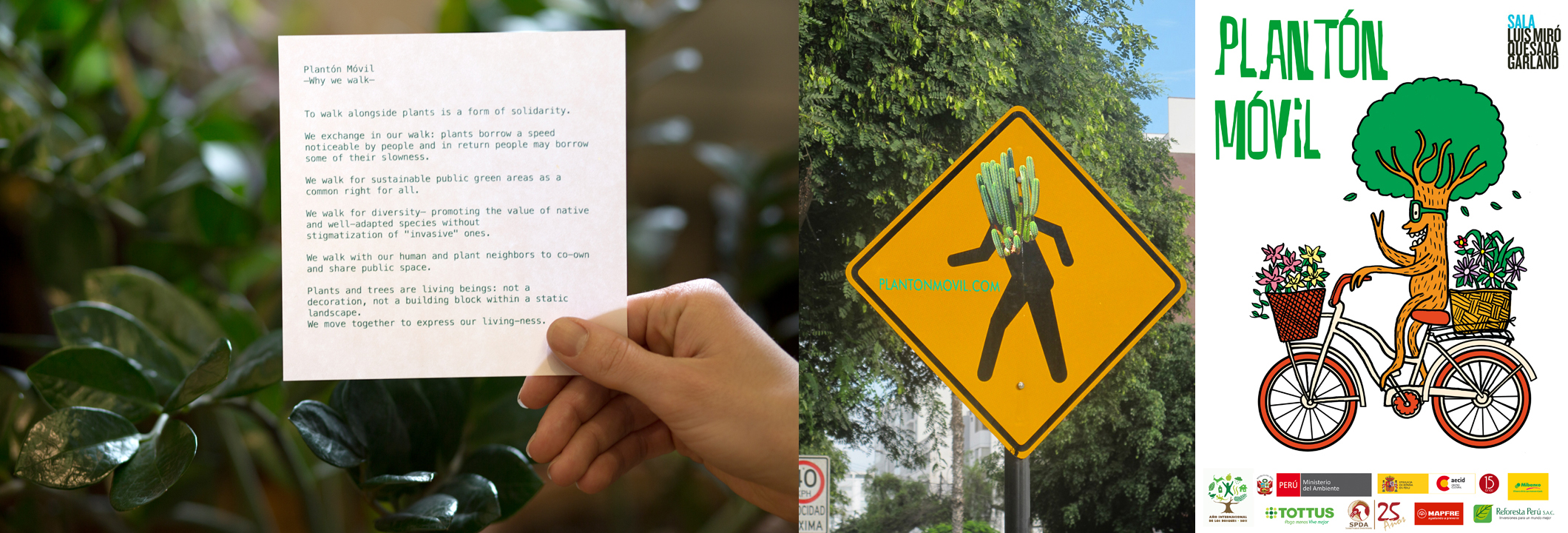

In 2010, I started Plantón Móvil to raise awareness of the mistreatment of plants and trees in the city, to advocate for accessible public green spaces as a basic right for all, and to promote the value of native species and other plants that are well-adapted to the local environment and its resources.

When walking around Lima, I had seen plants and trees treated with very little respect; they were drastically pruned overnight to keep parked cars and streets “clean” while their branches served as holders for empty plastic bottles. Their leaves were blackened by smog; some were used as bins and others even as bathrooms. I started to put myself in the place of these plants and trees, and thought that I would have left town a long time ago. Instead, the “green” is forced to sit there and accept this abuse because of its planted, “immobile” state.

Plantón is the word in Spanish for a sapling, a young tree that is ready to be planted into the ground. It is also the word for a sit-in. This project takes on both meanings: the green to be planted and the peaceful protest. People and plants get together to become a walking forest; it gives urban trees and plants the opportunity to take to the streets, demand respect, and claim their place in the city. After every mobilization, the plants and trees are planted to co-create a new public green space or contribute to an existing one.

Throughout these seven years of performing this action alongside different plant and human communities, I continue to learn how we can embody relationships by moving together.

Movement is commonly understood as the ability to go from one place to another. However, in the Aristotlean world view, the notion of movement includes not only the capability to change place but also growth, decay, and metamorphosis (Marder 186). Plants are our models for such forms of movement. Furthermore, in The Sixth Extinction, Elizabeth Kolbert notes the different speeds at which tree species “move” — that is, send their offspring to higher altitudes — to comment on their adaptability to the temperature increase in the Peruvian forests (Kolbert 158). In this case, although movement is still understood as a change in location, it is not measured by an individual’s motion but by that of a tree population following environmental conditions. Such framing of movement overrides the sessile nature of the individual by focusing on the movement of the collective.

Plantón Móvil works with the idea of movement in both of these senses: it performs the transformation of public space and its relationships, and it defines movement as a collective action.

Being Forest

There is a big difference between carrying a plant and being a forest. Plantón Móvil is not a group of people carrying plants, at least for the time being; we are the forest. This distinction changes the nature of the gesture and the way participants engage with the project.

The project does not intend to perform plant movement per se but to move-with as a form of solidarity. This is a walking forest composed of plants and people intertwined in various ways, and how we physically connect ourselves is key. Participants experiment, design, and improvise with all manner of materials including straps, elastic or fabric, backpacks, helmets, bikes, wheelchairs, skateboards, shopping carts, and other unpredictable wheeled objects and wearables.

Plantón Móvil is about lending our body to this other being so that it can borrow a speed that is noticeable by humans. It is not only about speeding up plants but also momentarily slowing us down. Joined at the base to a Thuja Occidentalis the same height as myself and moving in a sort of extremely slow three-legged race, I am reminded of where this practice lies. It is about exchange in what Donna Haraway calls “thick copresence” (Haraway 4). Directly experiencing the need to give-and-take weight and balance with another being in order to move forward is a metaphor that can be extrapolated to other relationships and makes tangible the unavoidable, but sometimes invisible/unperceivable, bonds between “others” in an ecosystem.

Action as Site

Although the project started in the second largest desert city of the world, it has been replicated in other urban areas, each of which has a unique relationship between humans and trees and plants. It is an invitation for inter-species connectivity that understands “site,” not only in terms of geography but as the discourse of cohabitation (Kwon 12).

Furthermore, climate change’s most popular examples present scenarios of overwhelming scale in a nature made abstract and located elsewhere. To practice in the city aligns with the need to de-capitalize nature in a similar way to what Timothy Morton argues for in The Ecological Thought. He laments the notion of Nature “as a reified thing in the distance, under the sidewalk, on the other side where the grass is always greener, preferably in the mountains, in the wild” (Morton 3). Plantón Móvil takes place in the city to serve as point of contact with issues that may seem to be happening elsewhere. It is not only about opposing to rainforest deforestation but taking responsibility on a daily basis, by being respectful and aware of the “green” that cohabits with us.

Making Odd Kin

“Staying with the trouble requires making odd kin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all” (Haraway 4).

Throughout the years, Plantón Móvil has been referred to by participants and observers as a “plant protest,” a “procession,” and a “parade.” I encourage these multiple readings of the same action because shared ownership necessarily allows for each of us to experience it differently. As we move together, all three conceptions are in fact present: the walking forest offers opportunities for political expressions of ally-ship, of poetic symbolism, and of celebration.

Most importantly, it hosts a growing community of people who come from different places and occupations to join around this common interest. The walks never go exactly as expected. I mostly plan and invite the exchange, but, thanks to the diversity of living and moving forms that the people and plants bring, the experience always unfolds differently.

Works Cited

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke, 2016.

Kolbert, Elizabeth. The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History. Picador, 2014.

Kwon, Miwon. “One Place after Another: Notes on Site Specificity.” October. 80 (Spring, 1997), 85-110

Marder, Michael. “The Place of Plants: Spatiality, Movement, Growth.” Performance Philosophy. 1 (2015), 185-194.

Morton, Timothy. The Ecological Thought. Harvard University Press, 2010.