With the Institut des Croisements, [1] choreographer, dancer and curator Arkadi Zaides unfolds a continuing engagement in human rights issues. His research-based art practice thinks through the entanglement of politics and the ways bodies (are allowed to) move. In 2017, Zaides embarked on the long-term performance project Necropolis, [2] considering the movements of people who are systematically and brutally stopped by border policies (Zaides in Noeth 51), highlighting the choreography that occurs in the social sphere. The performance project entails a “documentary approach to the contemporary geopolitical reality of migration” (Zaides 346).

Rather than providing a coherent, consistent analysis of the performance Necropolis, this text testifies of a co-production of knowledge from within the research-based, long-durational performance project of Necropolis, and its many off-springs, such as the NecropolisLAB and the continuously constituted virtual city of the dead called NECROPOLIS. [3] Rather than writing “about” an art-practice, this text came into being in collaboration with an art-practice. As another process of knowledge production is at stake, this text is not single-authored, but rather presents a hybrid constellation of different voices from within the collaborative process itself. Also, this text sometimes follows the logic of side thoughts, indicated with comments in footnotes.

In the text, the different voices are marked by different color codes, rendering transparent in a legend, from the onset, the accountability of the authors in the networked thinking. Also, in the accompanying short bio of these authors, the position from where these authors think and speak is made explicit. As such, this text is organized and meets with academic requirements.

LEGEND (in alphabetical order)

44.764 registered deaths of refugees or migrants since 1993

(UNITED for Intercultural Action, June 2021)

Atelier Cartographique (Pacôme Béru / Julie Vanderhaeghen / Pierre Marchand)

Özge Atmış, Sixtine Bérard, Sophie Dedroog, Lore Duvivier, Rojda Gülüzar Karakuş, Amirsalar Kavoosi, Alma Kennedy, Jordy Minne, Daphne Stremus and Ilka Van Bijlen. (Students at Ghent University that participated in a workshop by NecropolisLAB and UGent)

Igor Dobricic (dramaturg and voice-over Necropolis)

Michel Lussault

NecropolisLAB

Philippe Rekacewicz

Christel Stalpaert

Arkadi Zaides

However, this legend of voices and color codes moves beyond its ostensible neutral and scientific-based use in cartography. In “traditional” cartography, a map is usually provided with a legend, explaining the symbols that appear on the map. It permits a better understanding of the symbols used. A legend is an important tool in communicating the meaning of a map in an unambiguous way. This legend, however, points at the impossibility of unambiguous thought-ownership. Thinking is never individual. The production of knowledge is always collaborative and never solely a product of the individual. Moreover, as Swiss writer Adrien Turel observed: most new ideas are to be found in the past, not in the present or the near future (in Mulder 18).

Some names in this legend refer to experts in various fields who teamed up with Arkadi Zaides and his team of Institut des Croisements in the NecropolisLAB, investigating from a multi-disciplinary perspective, specific opportunities for posthumous dignity for border-related dead migrants. In the NecropolisLAB, the collaborative practice of the long-term performance project Necropolis expanded with an “art-science-activist worlding” (Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble” 76) of performance scholars, human rights scholars, anthropologists, and specialists in cartography, application development and information systems design. The members meet remotely and online on a regular basis and come together physically for research residences, workshops and public presentations in various locations around Europe.

In Spring 2021, NecropolisLAB was supposed to reside in Lesvos and Evros in Greece, where a significant part of the research was to take place (but was postponed due to COVID19). Instead, the NecropolisLAB members met remotely and online every two weeks. In March 2021, a workshop on Necropolis took place at Ghent University, in collaboration with the research centre S:PAM, several members of the NecropolisLAB, and students participating from diverse fields of study. In June 2021, a performance and workshop of Necropolis took place in Montpellier, mobilizing again several members of the NecropolisLAB. 25-28 November 2021, another research residency and workshop took place in Lyon, in collaboration with the École Urbaine de Lyon of the University of Lyon.

This text is an in-between report of the ongoing collaborative practices of the NecropolisLAB in relation to the research-based performance project Necropolis. Every performance of Necropolis is a preliminary culmination point in the many-faceted and long-term process, placing the body and choreography (in its most expansive sense) as key attention points. The Necropolis performance calls upon the local (European) audiences to individually and collectively acknowledge the death of people who are dying on the European shore by mapping their place of death, performing a grave location search and a walk towards a grave of a migrant. The NecropolisLAB gathers to imagine another type of movement; the virtual movement of the deceased’s loved ones to burial grounds they might never be able to visit physically. A key element NecropolisLAB members thoroughly reflect on is how to acknowledge and document this vast community of people? How to visualize the dead back into the social order with respect for ethical concerns? How to enable individual and collective mourning over and with the dead? How to activate social and legal shifts from anonymity to identity, from invisibility to visibility, from disempowerment to affirmation? How can a virtual space and technology be used to imagine spaces of communal mourning, resurgence and repair, not only as a funerary ritual for the family of the dead, but also as a site of commemoration for public acknowledgement of the numerous migrant deaths? For, as Judith Butler pointed out in her lecture Bodies That Still Matter (2018): “to grieve another is to stand in relation to that other. It is a social relation, one between people […]. The public acknowledgement of loss is crucial to the act of protest.”

In their participatory research, the members of NecropolisLAB engage and collaborate in a relational way of doing research, researching issues that also affect them. This relational thinking does not allow them to proceed in confidence, they consistently cultivate a tolerance for ambiguity. Their thoughts are entangled with their (sometimes conflicting) thoughts as spectators during numerous performances of Necropolis, with their activist engagement in humanitarian action, their particular scientific research and with human rights advocacy. In fact, none of the authors mentioned in the legend can actually be reduced to the words indicated by one color. Rather, these colors are points of connection in the hyphenated thinking of the art-science-activist worlding at work in the co-creative and collaborative praxis of the many-faceted Necropolis project. As such, this legend does not represent a consensus of multiple voices in multi-disciplinary thinking. It testifies of the experience of participating in a heterogeneous connection of entities, in a hyphenated thinking, allowing for dissensus to pop up, also within one entity.

The students who participated in the workshop of Necropolis (8-19 March 2021) at Ghent University are also part of this art-science-activist worlding and are hence also attributed a color code in the legend. During the workshop, there was more at stake then mere transfer of knowledge. Coached by NecropolisLAB-members Arkadi Zaides, Christel Stalpaert, Pacôme Béru and Julie Vanderhaeghen, the workshop setting deliberately challenged a vertical epistemology and reshuffled the hierarchical relation between experts standing “above” — having knowledge of and access to appropriate methods and techniques — and lay persons “below.” The students were engaged as active participatory researchers, pressing on ethical issues, and bringing critical issues to the fore from diverse fields.

The legend that goes with this text not only features multiple authors and their affiliation. It also features the voices and bodies haunting the performance project of Necropolis. The reference to the 44.764 registered deaths of refugees or migrants since 1993 in the legend refers to its main documentary material; an open-source database maintained by UNITED for cultural action since 1993. It collects reliable data on refugee deaths since 1993 and is published yearly on June 20th, World Refugee Day. As of June 2021, when the latest updated version was released, the list included data of 44.764 reported “migrant deaths”: refugees and migrants who lost their lives on their way to the continent and in their quest for European citizenship. Most probably thousands more are never reported. The N.N. in the list refers to this growing number of bodies that are labeled as nomen nescio in the list, a Latin expression used to signify an anonymous or unnamed person.

An important aspect of the performance Necropolis lies in the choreographic gestures of care for these dead, performed by everything [4] and everyone involved in the research-based performance. Each choreographic journey on stage starts from the very point where the theatre venue is located, and embarks on a navigational choreography with the dead, mapping local cases of migrant border deaths that are mentioned in the list. The local research preceding every performance is done in close collaboration with local authorities, hospitals, archives and experts. As such, every performance entails an ever-expanding collaborative practice of deep-mapping, generating a “form of jointly dealing with questions of responsibility” (Noeth 51). As research precedes every performance, data continuously feeds the performance, but the performance also updates the research and the archive of UNITED. The voices of these migrant deaths resonate in the ever-expanding heterotopic space of NECROPOLIS that the performance project generates: the body of data collected, the physical and choreographic movements of bodies – human and more-than-human – the voice-over by dramaturge Igor Dobricic, amplifying the voices of the dead, sometimes retrieved from oblivion, most of the time anonymous and forgotten …

As this legend goes with a deep-mapping of the ever-evolving heterotopia of NECROPOLIS, it functions as an ironic rem(a)inder of the resolutely flat perspective we have become habituated to in mapping the earth and its inhabitants. As the British geographer Stephan Graham explained in his book Vertical, this flat perspective holds a perceptual as well as a political failure, “for it disinclines us to attend the sunken networks of extraction, exploitation and disposal that support the surface world” (in Macfarlane 13). Thinking the entanglement of human and nonhuman matter opens up a new perspective on what “dead” things evoke, allowing missing bodies, dead bodies, body parts, and the mass of decomposed bodies to matter. This text hence also testifies of a thinking together in the storied place of NECROPOLIS, the city of the dead that erupts along the performance project, where voices of deceased migrants resonate from beneath the surface of European territory.

Their voices — entangled

Their conversations — a mesh

Any text reduces the deep-listening in conversation and the networked thinking-with-things to sequential words on a flat surface. Interruptions, hesitations, silences, the breath-taking in between, … all of these are absent in this line-up of words. A linear text ruins relationality. It converts the interchange of human and more-than-human connectivity to brief, stilted fragments of individual thought. And yet, despite the unmappability of thought, this text engages in a deep-mapping of the art-science-activist worlding at work in the heterotopia of NECROPOLIS. Voices respond in different, but interrelated formats — words, quotes, critical maps, visuals, and the blanc spaces in-between. In the deep-mapping of a heterotopia, thinking operates as a relational engagement. Knowledge is produced in co-creative uncertainty, cultivating response-ability. It is an engagement with what Donna Haraway called “tentacular thinking” (“Staying with the Trouble” 31-34). Four concepts — deep-mapping, storied places, tentacular-thinking-with-things, and art-science-activist worlding — provide an orientation device in the meandering tracks of these thoughts.

Who owns these thoughts then?

Instead of proceeding confidently to one conclusion or a set of instructions to follow, this text hopes to find thought-stewards, connecting thoughts to particular social and cultural practices and to engage in response-ability. We hope that this text generates a cloud of thought work, in which it is hard to distinguish oneself from the mesh.

The starting point for every performance of Necropolis is a list of registered deaths of refugees or migrants who lost their lives on their way to Europe. This central source of data has been maintained since 1993 by the extensive civil society network UNITED for Intercultural Action. In June 2021, the list reported on 44.764 deaths, spanning seventy-eight pages densely filled with a long table, each row registering one death or group of related deaths –– sometimes hundreds. The list contains only those whose deaths have been reported. The toll in all is certainly much higher. Only a very small percent of the dead is mentioned by name, leaving the vast majority without identifying details.

Arkadi Zaides and his team delve into the practice of deep-mapping, counter-forensics and deathrights to retrieve the remains of those whose death is to this day mostly unacknowledged. Wherever Institut des Croisements resides with their long-term and research-based performance project Necropolis, the list is scrolled through. A local research starts from that particular place of the residency, in close collaboration with local authorities, hospitals, archives and experts, in order to gather further information on the names, gender, age, and origin of the deceased refugee or migrant, the place and circumstances of his, her or their death, and the location of his, her or their burial place. Grave location searchers team up to identify the exact burial location, they visit the location where the body is buried, pay respect to the grave and perform small deathrites. The visit to the location is filmed, following a pre-set protocol. These data continuously feed the performance. As such, the archive of Necropolis is ever-expanding and growing continuously, as, with every performance, another part of the invisible city of NECROPOLIS is retrieved. Every research-based performance of Necropolis is a public presentation in the long-term performance project. As such, Necropolis does not stop when the curtains are closed. The project has no clear beginning or end. […] It doesn’t stop, because this kind of killing doesn’t stop and will probably escalate (Zaides in Noeth 52).

The deceased migrants, the very same migrants that Europe tries so desperately to keep out of its territory, haunt an ever-expanding counteremplacement, as an inverted reality of European Utopia. On the basis of their deathright, the deceased migrants and refugees are granted citizenship[5] of NECROPOLIS, the city of the dead. Eventually, in the course of the research-based performance project Necropolis, a whole invisible city resurges from the underland. It houses tens of thousands of bodies that are absent, neglected, silenced, invisibilized, drowned, left unaccounted for, buried without proper documentation, … and it is expanding constantly.[6] As the voice-over in the performance recounts about NECROPOLIS:

We are rebuilding it out of what and whom we choose to remember. We are maintaining it by sharing our memories with others and we are letting it crumble into disrepair by which we individually and collectively forget.

NECROPOLIS resurges as a Foucauldian heterotopia of neglected bodies that can be imaginatively thought and remembered. This heterotopian affirmation is not about displaying a non-existent reality, but about displaying a hidden dimension of reality that can be imagined and that disturbs our superficial or indifferent thoughts. The continuously growing list of 44.764 registered deaths of refugees or migrants (UNITED for Intercultural Action, June 2021) is the starting point for displaying this hidden dimension of reality, and with every performance, this heterotopic space called NECROPOLIS expands.

The title of the project, Necropolis, ostensibly refers to an ancient form of burial ground: necropolis, the city of the dead. On a symbolic level, it strives to reactivate the archetype of an invisible, suppressed “community of the dead” that challenges and obligates us as a community of the living. Furthermore, it appropriates the literal effectiveness of the mythological imagination that Necropolis conjures up as a topos — a concrete metaphysical space. As a city, it is not a specific location but a meta-structure — the cemetery of cemeteries — that casts its shadow over the contemporary history and geography of Europe.

Throughout the performance project, we are mapping the invisible city of the dead — NECROPOLIS.

This map which is the territory, is stretching in all directions in the space-time interrelation of mythologies, histories, geographies, and anatomies of those to whom we have granted the entrance.

In that sense, NECROPOLIS is also what geographer Jean-Marc Besse called a “cartographic heterotopia”: a concrete, metaphysical spatial rendering of a hidden dimension of reality. It is the act of deep-mapping that “makes visible the unknown that nestles in the real” (Besse 31), exploring “the stories of places that lie beneath the surface” (Macfarlane 18). This practice of deep-mapping differs from the “flat tradition” of geography and cartography, and the largely horizontal worldview that has resulted from it. The cartographic heterotopia that comes with the deep-mapping practice unsettles the boundaries between nations and territories, rendering also the boundaries between life and not-life less clear. It is from this heterotopic space that voices call upon us and haunt us as a collective body.

A dark, warm, damp network of underground passages interrelating decomposing left-overs, assembling all the corpses, hundreds, thousands of them, into a sprawling landscape made of hardened cartilage and leathered skin into a raising architecture built on bones. One shared organism. A promise of an eternal life as exuberant and exhilarating as a violent death at sea. (voice-over Necropolis)

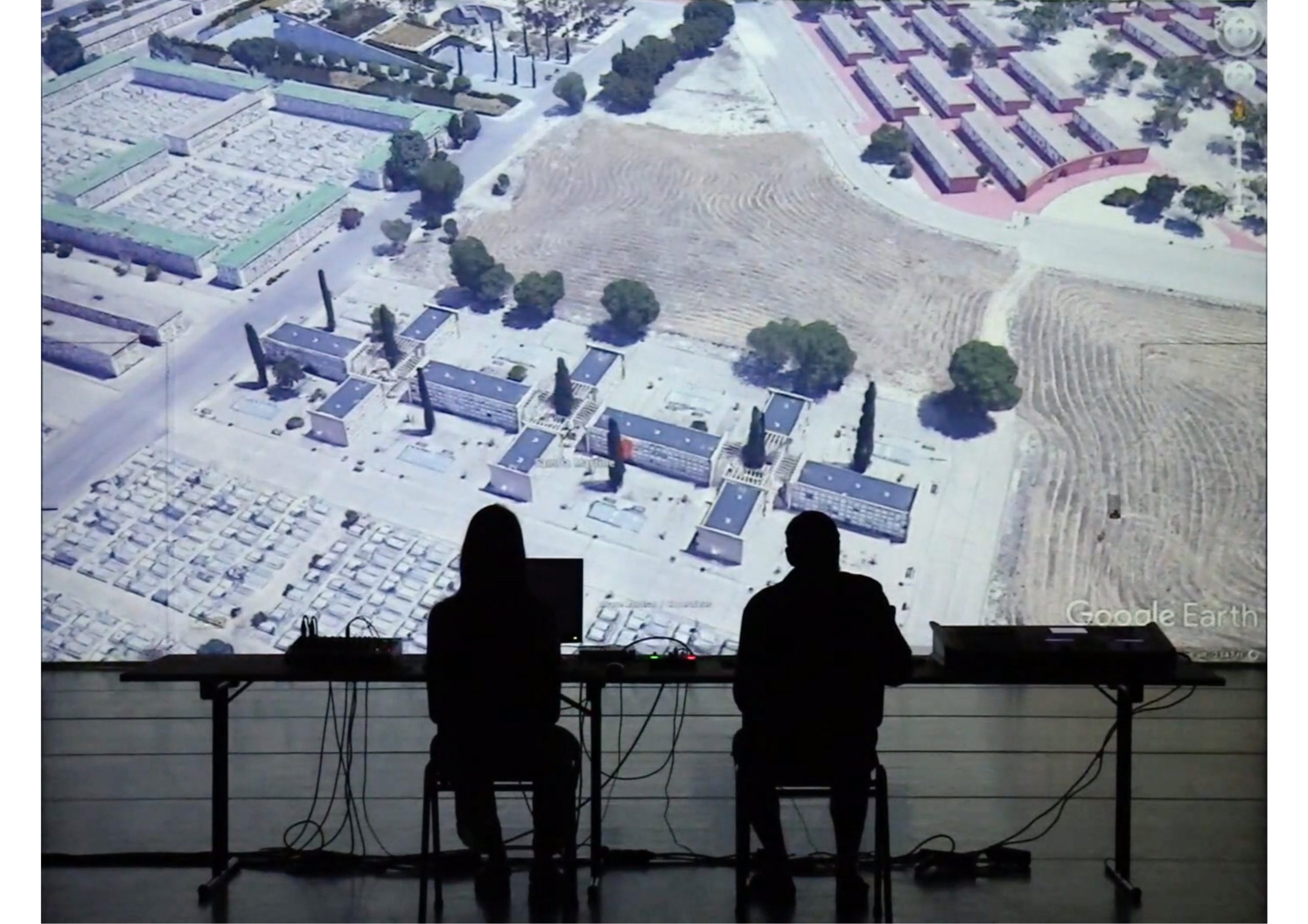

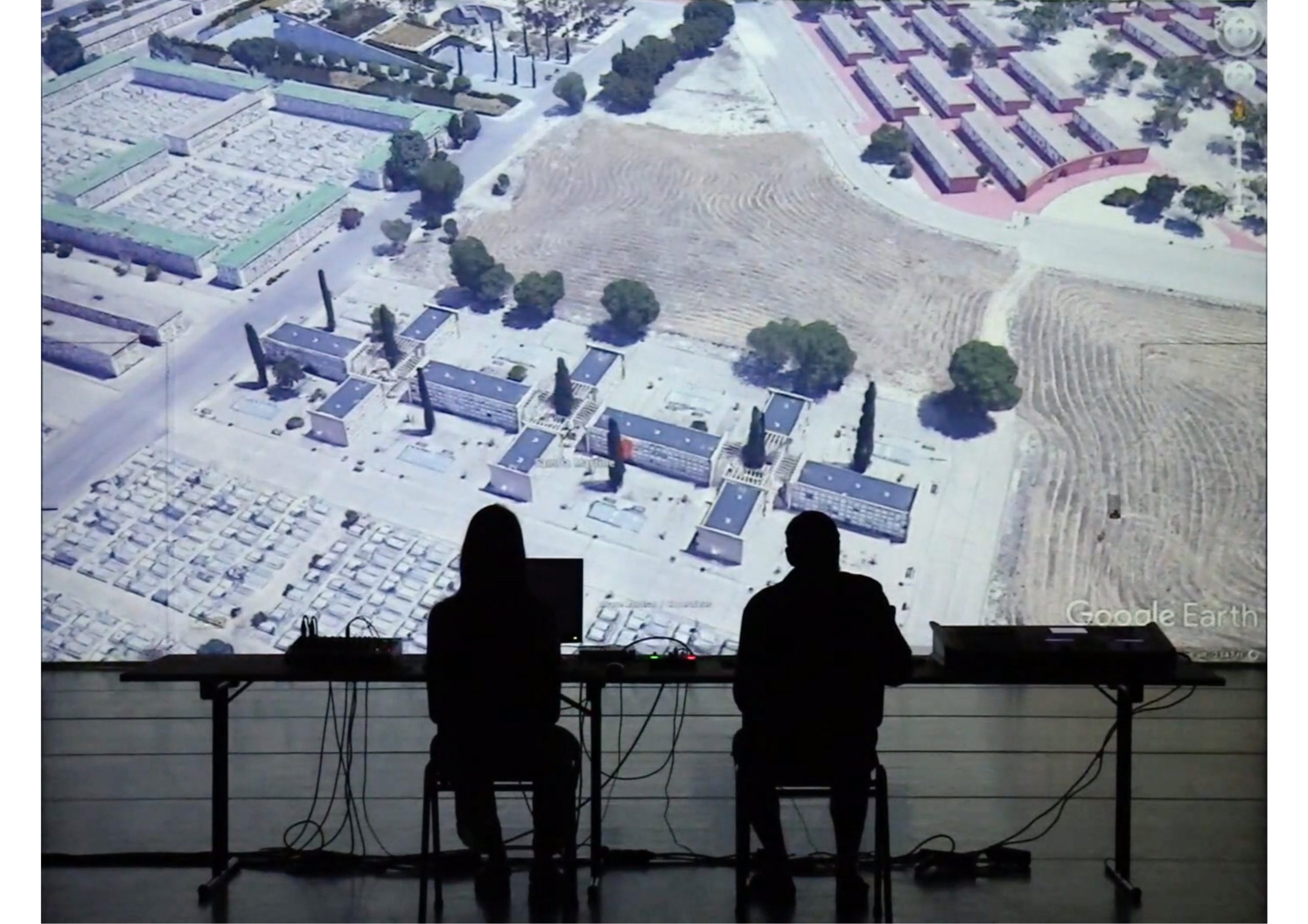

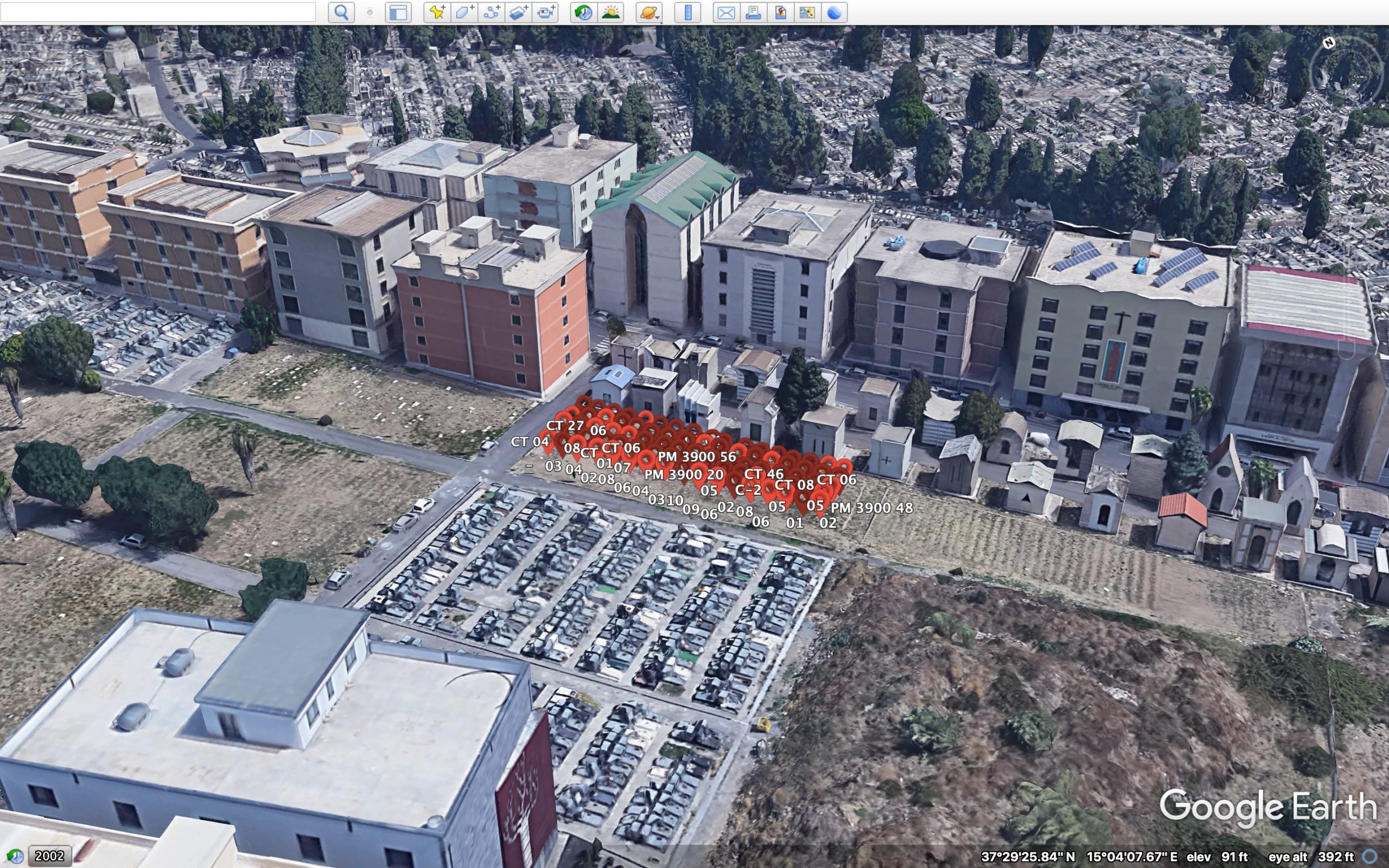

During the performance of Necropolis Arkadi Zaides, together with choreographer and researcher Emma Gioia, navigate through Google Earth on stage. With their backs to the audience, they use the technical equipment that is displayed on the table before them — computers as well as sound, light, and video operating devices. Google Earth is projected onto a large screen at the back of the stage. Zooming in on a mark similar to those that indicate one’s destination when one uses Google Maps, the two operators/performers reveal the location of a grave at a cemetery. Some of the marks are accompanied by names, others only have numbers. In this way, it is as if the names of deceased migrants are extracted from the underworld and surface from the satellite images. The operators on stage relate the names from the list to a real space via localization on Google Maps. They locate the places where migrating bodies ceased moving and reveal them as crime scenes to the audience. Zooming out and in, again and again, the data are materialized in words and numbers on the screen. The repeatedly zooming out and in on new locations becomes a repetitive choreographic phrase, assembling the names of the list in what a voice-over during the performance calls a “growing funerary encyclopedia.”

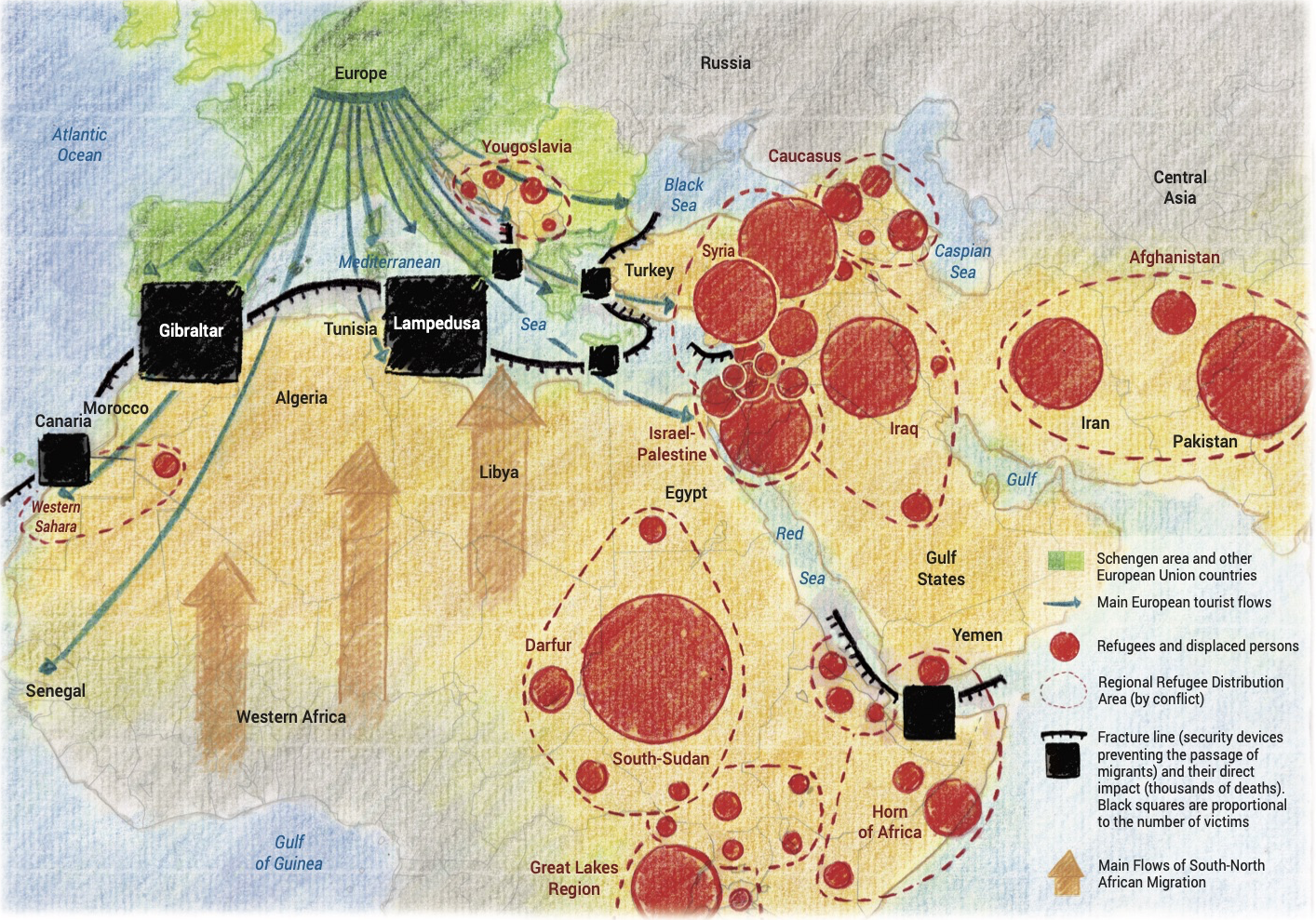

As geographer and critical cartographer Jeremy W. Crampton has argued, the methods of gathering data for map-making have changed considerably. Technological advances have re-valued the spatial project of mapping. Technologies such as Google Earth and Google Maps are primarily associated with the acceleration of mobility. Using them allows us to orient ourselves and find our way almost[7] anywhere on the globe. Many migrants and asylum seekers also use these platforms to orient themselves during their journeys. But platforms such as Google Earth and Google Maps are also the direct successors of maps, aerial photography, and other surveillance devices developed to support military operations and territorial control (cf. Zaides 350). On the other hand, as Crampton equally observes, the use of maps as an instrument of power, as a means of conveying and controlling geographical space, has not changed.

Mapping is involved in what we choose to represent, how we choose to represent objects such as people and things, and what decisions are made with those representations. In other words, mapping is in and of itself a political process. (Crampton 25)

Methods of mapping originated at the time of European colonial projects. The spatial project of Christopher Columbus, for example, is “a classic episode in the history of cartography and colonialism” (Crampton 48). It is a project that actually neglects and even erases the existence of existing indigenous places and people: “By reinscribing new identities on these places, and specifically Western Christian names, Columbus effectively created a new space that was compliant with Western beliefs, and which permitted it to be governed and controlled.” (Crampton 47-48) Despite opportunities for counter-mapping practices, seeking to contest dominant relations of power, current technologically advanced methods of mapping, such as Google Earth and Google maps, are still operating following the colonial project to discover, claim, and name space. They carry within them the history of racialization and dehumanization.

As such, inserting the coordinates of the migrants’ and asylum seekers’ graves on these devices, is a counter-mapping strategy, seeking to hijack them with information about the ultimate immobility – the deaths of those whose patterns of movement are “endangering” European colonial foundations. However, it is also not a coincidence that the action of the two performers/operators, scrolling through data and geographical terrain via a digital platform, and the repetitive action of zooming in and out, is reminiscent also of actions that often take place in surveillance control rooms, thus resonating with surveillance practices to which the deceased may have been subjected while still alive. In her book Movement and the Ordering of Freedom, political theorist Hagar Kotef observes the divide between “(1) the citizen, as a figure of “good,” “purposeful,” even “rational,” and often “progressive” mobility that should be maximized; and (2) other(ed) groups, whose patterns of movement are both marked and produced as a disruption, a danger, a delinquency” (2015, 63). She demonstrates how concepts of freedom, security, and violence take form and find justification via different and differentiated regimes of movement, also in mapping strategies.

Seeing more deeply, we detect the blind spots in cartography. There is no such thing as an innocent map. The first map of France was commissioned by the King of France. A map is an intellectual construction rather than a faithful representation of reality. The map’s promise of comprehension is misleading, its mimetic relation with reality is deceptive. There is more to spatial, social, or symbolic realities –– among others –– than the map represents. One could say that the performers/operators extract the bodies’ origin and ancestry from the body of data available, but, whereas extraction is usually connected with the deathly processes of colonial capitalism, extracting labor from bodies, minerals and oil from the ground, trees and water from the land, and fish from the sea, this mode of extraction generates factual knowledge and is an invitation to rethink the place of ethic and dignity within [geographical] information systems.

This deep-mapping practice is a kind of “radical cartography” (known also as “counter-cartography,” affiliated also with “critical cartography”). [8] What we call “traditional cartography” claims to be an exact science based on reliable data, and mapmakers pride themselves on creating a neutral and faithful image of reality. This approach ignores the political and social uses of maps and their role in propaganda or protest. “Radical cartography” could be described as a rich combination of sensitivity, art, sciences, geography, politics and social activism and militancy. It is a very committed and resolute mapping that serves the struggles for social and spatial justice, and to denounce questionable economic and political practices.

For decades traditional cartography had two assumptions: it claimed to be an exact science, based on reliable and scientific data, and also claimed to give a “neutral” and “faithful” image of the world, of the reality. We know, and critical cartographers have shown on many occasions, that this was simply an illusion —even if it has nourished the belief for generations of geographers, cartographers and other map producers along the modern and contemporary historical periods. Either they help a powerful king to have under the eyes the full extension of his kingdom and colonies in order to keep control of it, or they simply help to locate people and elements of the geography. They were answering the question “where are we” but avoided addressing the question “how the world really functions.”

Deep-mapping as a radical cartographic practice, also “challenges epistemological trends […] and the ‘flattening’ of knowledge systems” (Springett 623). As an epistemological concept, deep-mapping has been conceived of by French philosophers Bruno Latour, Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, and is manifest in speculative realism. In her article Going Deeper or Flatter: Connecting Deep-Mapping, Flat Ontologies and the Democratizing of Knowledge, the Australian artist-researcher Selina Springett explores the opportunities of deep-mapping as “a methodology and aesthetic choice” which relates to “a cross-boundary approach to place” (624). In fact, deep-mapping inscribes itself within diverse consciously performative acts (Roberts 2016, Springett 2015) to counter traditional mapping strategies. Creating a deep map of NECROPOLIS is in that sense “an act of undoing, a performative act that connects diverse disciplinary modes of enquiry and production, and blends ethics with aesthetics” (Springett 629).

Moving along the performers’/operators’ navigational choreography with Google Earth, we realize and recognize that “as twenty-first-century people, we are products of a map-saturated culture that privileges that spatiality of the grid” (Padrón 208). With the arrival of digital maps, we are even used to a navigational use of maps, rather than the old-school mimetic use. The information that the deep- and counter-mapping reveals, namely the ultimate immobility of the deceased migrant, is in sharp contrast with our swift navigational movements, along vast areas of green, blue and brown zones, leaving even country borders aside. We acknowledge the misleading nature in the consistency of a represented unity of a whole world. This suggestion of a “whole world” is in sharp contrast with the gates, walls, borders and fences the migrants face in Fortress Europa, with the territorially based sovereign state system that Hannah Arendt addresses in The Origins of Totalitarianism.

Bruno Latour calls the zoom effect of Google Earth “an assemblage as artificial as a fake perspective in a stage set” (“Anti-Zoom” 121). Indeed, the slider tool of Google Maps simulates a smooth and continuous process of zooming in and out on the Earth’s surface. This unified continuum is misleading, however, as the “zoom” is in fact an illusion composed of editing techniques such as fades, blends, and morphs. No human eye could maintain such a steady view across these different focal length scales. The engine provides the impression of a smooth and “neutral” optical transition between micro- and macro levels, with only the pixels becoming increasingly small. However, as Latour aptly observed, the zoom effect also masks its spatial politics. In fact, the visual formula of the zooming device follows the same principle as cartography, and is “similarly founded on the concept of a range of data whose projection depends entirely on the metric selected.” Besides, the continuous fluidity in changing focal lengths is given from a fixed position and indicated with the cursor, simulating a God’s eye view and a detached vision, neglecting any ecological or political context. The fluid and slick experience of this “montage effect” (“Anti-Zoom” 121) in Google Earth makes us forget the specific agenda of Alphabet Inc., its parent company. Like prestidigitators use the public fascination to discretely set up their tricks in plain light, those kinds of tools embed in their conception and their context of production intentions that are not displayed at first. Often related to data-mining and profiling toward an economic profit, they target and impact bodies and territories, if not always physically, at least in their representations, and at a large scale.

Latour suggests that “good artists do not believe in zoom effects” (“Anti-Zoom” 121). Likewise, in Necropolis, while navigating Google Earth, the voice-over reminds us:

As we keep moving above, around and through Necropolis, let’s not forget everything we see in this landscape of death is made of ourselves. […] From the North a glacier of border regulations and bureaucratic classification. From the West a narrow gorge of falsified history of conquest and enslavement, of abuse and exploitation, of greed and betrayal.

The voice-over in Necropolis testifies of the barbaric flip side of the map as a tool of civilization and its entanglement with the colonial project to discover, claim, and name. “There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism,” the voice-over says, referring to Walter Benjamin’s seventh thesis on the philosophy of history, in which he states that civilization is a crime scene (256). As such, the deep mapping during the navigational choreography with Google Earth also reveals how the territorial map not only hides its representational strategies, but also its own genesis: the conquest of territory and the violent history of European expansionism, colonialism and imperialism. Mapping deeply, we encounter the name places on Google Earth as vexed places, being disturbed and burdened (Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble” 133) with the barbaric flipside of the Western history of civilization.

“Refuse to investigate the crime,” the voice-over continues, “and barbarism will return to haunt you. It is important to acknowledge that this most obvious truth about history is the one you are most inclined to forget.”

But how to investigate this crime? How to counter the politics of the zoom effect? How to connect rather than detach?

Following Latour, a potential antidote to the reductive situated view of the zoom effect, is the technique of layering and “connectivity” without reduction (“Anti-Zoom” 124). Connectivity, Latour says, sidesteps the visual reduction by reintegrating “the matter of space-time; a route or trajectory” (“Anti-Zoom” 123). Connecting through a particularly traced path counters the reductive zoom-tool interaction. In other words, a deep-mapping not only generates a critique of “flattening” and racializing knowledge systems. As an aesthetic tool, it also provides alternative cartographies, crossing and connecting temporal, spatial and disciplinary boundaries. Flat Earth becomes a storeyed or multilayered place, which associates rather than reduces situated views. It not only reveals the specific reductive politics of the zoom-effect, but it also provides an alternative of storied places. Narrative plays a central role here. In the book Terra Forma, Frédérique Aït-Touati, Alexandra Arènes and Axelle Grégoire explore these “potential cartographies.” They propose to invent cartography from the “point of life,” rather than from the “point of view.” Proceeding from the blank spaces in maps, their adventure constitutes “une nouvelle imagination créatrice de l’habitation,” generating a subversive geo-aesthetics of the Anthropocene (Lussault).

Connecting the routes or trajectories of migrants with occidental expansion in the past, Necropolis detects a political failure in our expansive, horizontal world-view that is also part of the history of cartography. We become aware of the violence with which map making is intertwined. This is “the principle of ruin and destruction” that lies “at the heart of the cartographic drive,” and which the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges demonstrated in his story On Exactitude in Science (1946). Borges pushes the utopian ideal of cartographic representation to the absurd limit of copying and imitating an already existing territory in an absolute map on a scale of one on one. In this short story, the utopian idea of Empire is the “production of a whole new hallucinatory reality” (Bosteels 132). What resurges in the blank spaces on the Euclidian fields of the territorial map are the corpses haunting these spaces, and with them resurge storeyed and storied places.

“When confronted by such surfacings it can be hard to look away, seized by the obscenity of the intrusion,” says the British writer and walker Robert Macfarlane (14). Indeed, seeing and listening deeply, through the cracks caused by the deep-mapping practices in Necropolis, and from the storeyed places laid bare, the migrant’s individual stories resurge. [9] The storeyed place becomes a storied place. Following environmental philosopher and anthropologist Thom Van Dooren, the understanding of a place as storied highlights “the way in which places are interwoven with and embedded in broader histories and systems of meaning through ongoing, embodied, and inter-subjective practices of ‘place-making’” (67).

The cracks that come with the activities of deep-mapping allow for individual stories to resurge and emerge. The topographic names of Jabbeke, Merksplas, Vottem, Lampedusa, LeNiamh, Dattilo have become more than objective spatial locations on a map. From the disturbed underland, the tragedy of transmigrants at the refugee tent camp stories [10] the vexed place of Jabbeke. The migrant shipwreck on 03/10/2013 stories the vexed place of Lampedusa; the shipwreck on 8/8/2015 stories the vexed place of LeNiamh, the shipwreck on 11/7/2015 stories the vexed place of Dattilo, … Beneath the seemingly flat surface of the vast mass of green, brown and blue on Google Earth, at the bottom of the sea, on the shores, and inland, a mass of decomposed bodies and body parts stories European territory. Vexed places become storied places.

In a sense, this resurgence is also an emergence: by bringing “hidden facts” to light, it transforms them by this action. The graves, bodies and displacements that appear on maps are not analogous to what they are or were, they are changed by this appearance, they are transformed both as debatable facts and as supports for narratives and interpretations. As Frédéric Pouillaude indicates, the translation of documentary footage to the sphere of movement and choreography demands substantial modifications (xviii). The archival and documentary material are not points of departure or inspiration in Necropolis: they remain present in the final work, but they are also tampered and interfered with, altered, and modified in order to highlight their physical and choreographic qualities.

By confronting the dichotomy between the dead and the living through a documentary approach to the contemporary geopolitical reality of migration, Necropolis allows the spectators to be literally implicated, and hopefully to recover their own sense of accountability.

Acknowledging storied places means thinking-with these corpses and re-thinking-through their singular narratives. It is an exercise in thinking together in a thick presence and a deep time, with tentacles towards a troubled past and a precarious future. In this tentacular thinking, all our senses are engaged [11]: we hear the migrant dead’s hope of secretly boarding lorries heading for the UK by ferry. We sense their courage of undertaking extremely dangerous journeys in the hope of reaching the UK, often at the instigation of gangs of human traffickers. We feel their fear of experiencing problematically low temperatures and oxygen levels in the lorries during their journey to the UK, … Van Dooren would call this deep-listening “a powerful attunement to storying” (63-86) through the cracks in the seemingly paradise-like place of Europe. This tentacular thinking is also tentative thinking, in the sense of speculative thinking. As Haraway put it, the myriad of tentacles in tentacular thinking “weave paths and consequences, but not determinisms; they are both open and knotted in some ways and not others” (“Staying with the Trouble” 31).

From the Google Earth image of our planet floating in space, the performers/operators gradually zoom in to this virtual representation of geography until we recognize the cemeteries that grave location searchers have outlined. We zoom in further, to discover the particular architecture of the graveyard from above. We can zoom further into the exact points where the graves are located, and hover above them. Poststructuralist anthropologist Tim Ingold called this hovering, god-like perspective the Global view of the environment. He characterizes these global views as opaque, massive, objective, detached, distant, centripetal, confrontative, visual and total. “Images like these of the Earth,” Bruno Latour says, “from out in space led us to believe that we humans live on the surface of a globe” (“Critical Zones”). Ingold valorizes the alternative of a spherical view, which is transparent, soft, subjective, close, surrounding, centrifugal, acoustic, and experienced (45).

At times, the Global gaze from above, is downscaled by such a spherical view in Necropolis. A video capturing the walk of the grave stewards from the cemetery gate towards that same grave appears on the screen. The camera is held in front of the body at chest level, making it impossible to determine who holds it. It is a simple, silent walk toward a grave, toward many different graves at many different locations, always at the same pace, conveying an embodied practice. The embodied practice — though also mediated — is in sharp contrast with the surveillance device of Google Earth, zooming in on a grave from above. The video documentation of the walks to the graves allow us to get closer to the bodies, both in a literal and a figurative sense of the word, from an eye-level perspective. The visit to the cemetery, and the walk towards the grave, as respectful gestures to each grave identified, strives to articulate an embodied investigation in the sense that Haraway proposes in her essay Situated Knowledges (“Situated Knowledges” 585).

Moreover, the entanglement and confrontation of these two perspectives – the “gaze from above” with its colonial roots, and the embodied, situated knowledge proposed by Haraway – are crucial, and pave the way toward a liminal space that interrelates the geographies, mythologies, histories, movements, and anatomies of individuals who lost their lives on the way to Europe. Ingold would call this “a dialectic of engagement and detachment” (45). Latour would call this an “interface between the deep earth below and the vast expanse of space above. […] it has a topography very different from that of a planet viewed from space […]. The result is this enigmatic and idiosyncratic figure some scientists have called Gaia inside which all beings are enmeshed.” (“Critical Zones”) Thinking through the entanglement of human and more-than-human matter in Necropolis opens up a new perspective on what “dead” things evoke, allowing missing bodies, dead bodies, body parts, and the mass of decomposed bodies to matter. It is a “mode of thought in which discrete boundaries are sensed as permeable” (Bohm xvi). This tentacular thinking-with-things is also a tacit production of knowledge; it is “a hugely consequential, mind-and-body-altering sort of commitment” (Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble” 34).

The Mass Grave

Found dead Various dates, two hundred and twenty-two bodies located at Cimitero Monumentale di Catania, Sicily, Italy. Up to six bodies are buried in each tomb.

Name, gender, age Unidentified, except the graves of Muyasar Bashtawi, Touray Kebba, Malik Abdel, Romini Hossain, Kelle Osman, Mustafa Jumaa

Region of origin Various

Cause of death Died while crossing the Mediterranean Sea

Grave location search Giorgia Mirto

Grave localization Arkadi Zaides

The Single Grave

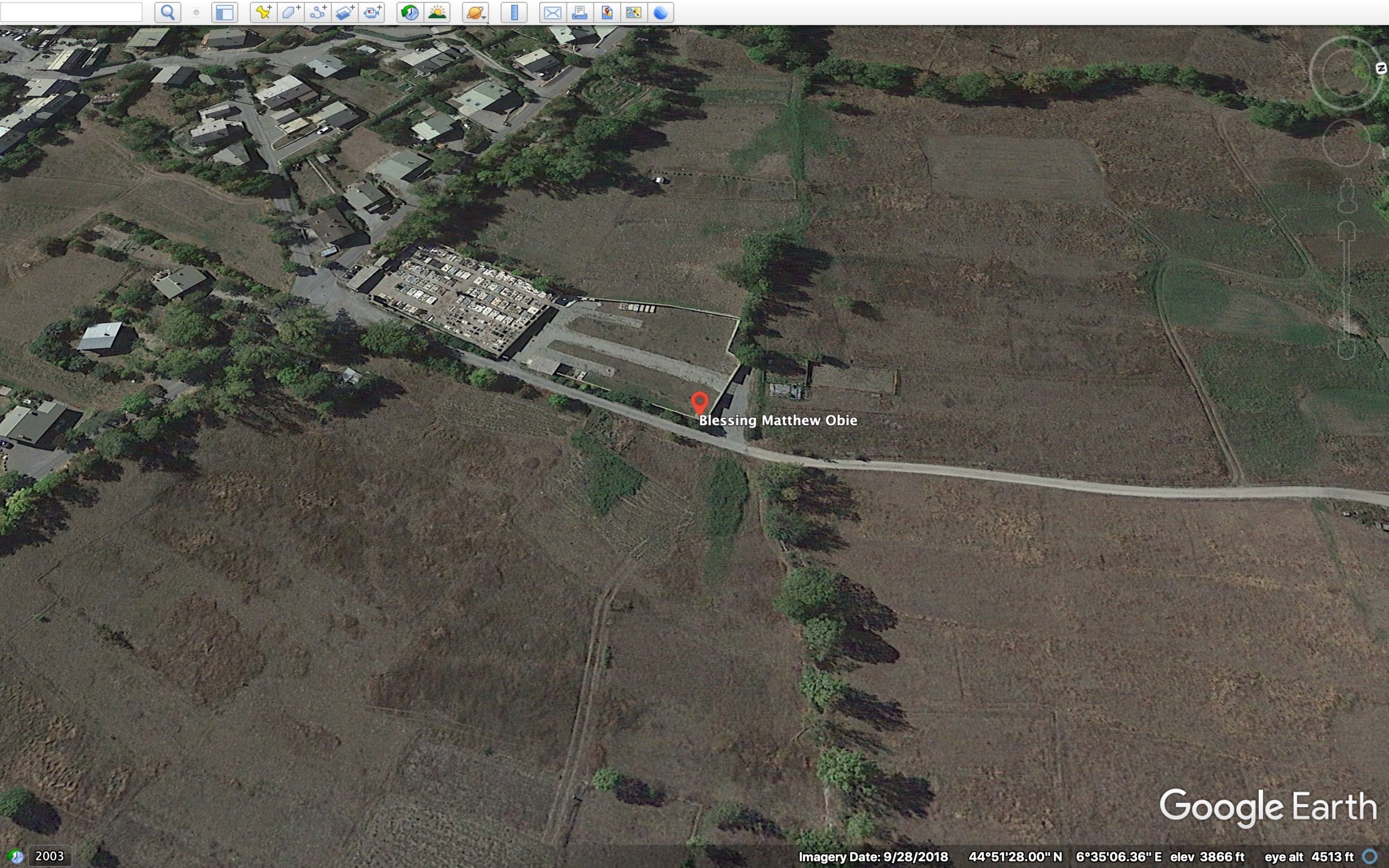

Found dead 07/05/2018

Name, gender, age Blessing Matthew Obie (F, 21)

Region of origin Nigeria

Cause of death Drowned in Durance river near Briançon (Alps, French/Italian border) while fleeing the police

Source Vivre/CDS/Francetvinfo/20MFR/IOM/DICI/Liberation

Grave location search Yari Stilo

Grave localization Yari Stilo

The Hospital

Found dead Various dates, around 25 bodies kept in container next to the offices of the forensic pathologist Pavlos Pavlidis for approximately 4-6 months, if no claims for the bodies are being reported the bodies are buried at the Sidiro Muslim Cemetery

Name, gender, age M and F

Region of origin Various

Cause of death Died while crossing the Evros River on the Turkish Greek border

Grave location search Tilemachos Tsolis

Grave localization Tilemachos Tsolis, Arkadi Zaides

Donna Haraway’s concept of tentacular thinking does not pretend to emerge from one source of thinking. A myriad of tentacles is needed, with many appendages. It is a co-creative thinking-with and thinking-through bodies and things. In fact, the concept of deep-mapping, as an aesthetic tool enabling a reflection of epistemologies, crosses not only individuals, but also and preferably disciplinary boundaries (Springett). We could say that the long-term research-based performance project of Necropolis is involved in what Haraway calls an art-science-activist worlding that generates a mode of thought in which the discrete boundaries between disciplines and research domains are permeable. The art project renders an understanding, an imagination, but also the creation of a world teaming up with science and activism. This “art-science-activist worlding” [12] transcends mere interdisciplinary scientific research, as another production of knowledge is at stake. The hyphens in Haraway’s concept indicates that these worldings produce knowledge in relationality. Knowledge is not produced in one of the fields of the “arts,” “science,”’ or “activism,” with the other field functioning as an auxiliary science. It is exactly in the connecting hyphens that knowledge resurges.

This particular production of knowledge from a hyphenated position was experienced in the workshop of Necropolis, conducted at Ghent University from 8-19 March 2021. The workshop gathered NecropolisLAB members and an interdisciplinary group of students who worked on a joint project together. The workshop was initiated by Arkadi Zaides and Christel Stalpaert. Julie Vanderhaeghen and Pierre Marchand represented Atelier Cartographique in one session, a Brussels-based studio, specialized in cartography, application development and information system design. As the workshop on Necropolis was embedded in Eva Brems’s university wide [13] optional course “Human Rights: Multidisciplinary Perspectives,” the artistic practice of Necropolis was brought into the human rights framework. A very diverse group teamed up to investigate opportunities for posthumous dignity for border-related dead migrants. The points of discussion we embarked on were the following: How do we imagine alternative platforms for individual and collective mourning? What are the rights of one’s death to be investigated and do the same rights apply to the community of the undocumented ones? What are the legal and ethical concerns when revealing information about the dead and making it part of the public domain? And can a work of art transgress and challenge these conceptions?

The hyphenated position of everyone and everything involved was clear from the start. Not only was the research in the workshop conceptualized and realized through diverse fields (art, science and activism) and diverse disciplines such as Law, Conflict and Development Studies, Performance Studies, Human Rights Studies, Public Administration and Management, and Communication Sciences. Also, our position as student, teacher, artist, researcher, software developer, … shape-shifted throughout the workshop. Our mind-set was recalibrated repeatedly, as our thinking unfolded in a network of interconnectivity.

Thinking through our hyphenated position, we experienced the internal conflict between ethical issues of privacy and our urge to acknowledge and document this vast community of people, of migrant deaths, the urge to activate social and legal shifts from anonymity to identity, from invisibility to visibility, from disempowerment to affirmation. Ethical issues were at the heart of the discussion and until now NecropolisLAB has been rather cautious regarding this matter. When collecting personal data, privacy rights and confidentiality should be respected with a view to ensuring the safety and security of the migrants of whom information is collected and shared as well as their family members. In collecting and handling information containing migrants’ personal details, searchers need to act in accordance with applicable law and standards on individual data protection and privacy. They should also ensure informed consent. [14] From the activists’ perspective, it seems that their approach is usually very firm about the need for sharing information about the locations of the graves of migrants. From their point of view, this information should be public to assure the shift of debate and public opinion.

While participants of the workshop were at no time being pushed into activism, they gradually became grave-stewards. They did not become activists, but they were activated by the knowledge produced during the art-science-activist worlding of the workshop. Thinking through (the lack of) European jurisdiction for systematic forensic investigation; the diversity in the migrant death management systems; burial rituals as a humanitarian mechanism; . . . we found ourselves in an entangled thinking-with-the-dead.

It was not part of the group assignment, but during the workshop, some anonymous deaths in the UNITED list were identified and some graves were localized, by students and teachers, and by some friends and relatives that became involved along the way. As such, a growing body of participants intervened in the actual data of the UNITED list, became involved in the process of reporting back to UNITED, became responsible for corrections in the list, pointed at a misspelling of a name, located graves and performed small rituals of commemoration. Retrieving the identity of someone indicated as N.N. was experienced as performing a gesture of care. We noted that we started to call the migrant death “cases” by their given name. Retrieving this given name from oblivion created an intimate relationship. It made us aware of our own fundamental nonseparatedness from the more-than-living-world. This shocked us into recognition of the inescapable interdependencies and shared contingencies between the living and the ten thousands of migrant border deaths.

The city of the dead is this city, and this city is theirs. As you walk out onto the street, remember. Every blade of grass pushing its way through the pavement is growing from their rotten flesh. Living trees are their tombstones. The air that you breathe is their sigh. You inhale and they are inside of you. You exhale and the wind blowing through the branches speaks in their voice. Please, listen.

Necropolis refers to an ancient term for a burial ground: the city of the dead. It strives to reactivate the archetype of an invisible, suppressed “community of the dead” that challenges and obligates us as a community of the living. As such, Necropolis reclaims what forensic anthropologists M’charek and Casartelli called the deceased migrant’s “relational citizenship” (738). The citizenship that Necropolis articulates goes beyond state governance. It acknowledges people “as part of a human community” and is “bounded by ideas about humanity” (ibid.). Through this “citizenship as a relationship of care” (ibid.), the living are accountable for the dead, “bodies become people, individuals who belong to the community, rather than objects or waste to be disposed of” (ibid.). Feeding the data with local cases and performing these serene acts of commemoration, enabled us to be implicated, recovering a sense of accountability.

The students decided that the migration narrative would not be part of their report, because it is not their story. To be graded for that story would be at odds with the intimate relation of care that they maintained during the workshop. We accepted their claim from their perspective as gatekeepers and grave stewards.

Allowing the migrant border deaths entrance into the city of the dead, and making them members of the community of NECROPOLIS, we put into practice the concept of “citizenship as a relationship of care” (M’charek and Casartelli 738). In connecting with the collaborative long-term performance project of Necropolis we unfolded a practice of “speaking resurgence to despair.” When we performed our small rituals of commemoration as temporary grave location searchers, we teamed up with “cold” data and bodies, activating “processes of resurgence” and creating “conditions for ongoingness” (Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble” 37). [15] These are of unquantifiable value in the scorched, parched, drowned and infected landscape we currently inhabit.

These ever-expanding collaborative practices, this “form of jointly dealing with questions of responsibility” (Noeth 51) did not guarantee an instant result. When the report and subsequent grading system were uncoupled from the migration narrative, time seemed to be “wasted.” However, it was this non-gradable and non-quantifiable production of knowledge that had a profound impact on our seeing and listening differently. While we are used to scientific thought effectively moving forward, this participatory thought seemed to unfold slowly, but insistent, “staying with the trouble, yearning toward resurgence” (Haraway, “Staying with the Trouble” 89), sticking to the thickness of the present. “In a time of accelerating abstractions and seamless digital representations, it is this insistence on facing the inconvenient messiness of daily, corporeal experience that is perhaps most radical of all” (Bohm xi).

And this participatory thought does have an accumulated effect. An ever-growing number of migrant border deaths are acknowledged as part of the human community of NECROPOLIS. At this moment, NECROPOLIS, the city of the dead, houses more than one thousand citizens. This means that more than 1000 graves have been located and mapped. Also, the community of gatekeepers and grave stewards is ever-expanding, cultivating conditions for ongoingness. As Necropolis does not stop when the curtains of the theatre are closed, the thinking does not stop when a text is written. We do not recompose the dead in Necropolis, we become them. In our intimate connection with the counteremplacement of NECROPOLIS, their voices speak through us. What is at stake, then, is a persistent resurgence of the dead in this barren landscape we inhabit, continuously and dynamically sprawling into a thousand plateaus.

Necropolis, its map and its body are made out of dead data that we collect and memorize. We are rebuilding it out of what and whom we choose to remember. We are maintaining it by sharing our memories with others and we are letting it crumble into disrepair by which we individually and collectively forget.

About the others, those still alive outside, we know nothing.

Institut des Croisements : Institut des Croisements is a French non-profit association, founded and directed by Simge Gücük & Arkadi Zaides with Benjamin Perchet as president. The association is supported by the French Ministry of Culture/DRAC Auvergne Rhône-Alpes. Institut des Croisements’ mission is to promote Zaides’ work as well as to represent contemporary artists and produce cultural events. (https://arkadizaides.com/about) ↑

Residencies took place in STUK (Leuven), Workspacebrussels (Brussels), Charleroi Danse (Brussels), WP Zimmer (Antwerp), Compagnie THOR (Brussels), RAMDAM un centre d’art (Sainte-Foy-lès-Lyon), Studio Cunningham (Montpellier), CCN2 (Grenoble), Studio Cunningham (Montpelier), CCN (Nancy), Pact Zollverein (Essen), HAU (Berlin), le ballets C de la B CoLabo (Gent), 1927 Art Space (Athens). Online performances took place as part of Tanz im August (Berlin, Germany, 26 August 2020); as part of the closing event of the Atlas of Transitions EU project (Bologna, Italy, 7 December 2020); as part of “les Vagamondes” festival at La Filature (Mulhouse, France, 15 January 2021); as part of the PimOff residency program (Milano, Italy, 26,27 May 2021); as part of Divadelná Nitra International Festival (Nitra, Slovakia, 6 October 2021). Live performances took place as part of FIT Festival (Lugano, Switzerland 4/ October 2020); Gessnerallee (Zürich, Switzerland, 14-15 May 2021); at Sort/Hvid as part of Danish festival for performing arts (Copenhagen, Denmark, 3–4 June 2021), as part of the Montpellier Dance Festival (Montpellier, France, 23-25 June 2021); at Dansens Hus (Stockholm, Sweden, 30 September, 1-2 October 2021); as part of FACYL, el Festival de las Artes y la Cultura de Castilla y León (Salamanca, Spain, 8 October 2021) For an overview of the upcoming residencies and performances see https://arkadizaides.com/. ↑

Please notice the difference in writing of Necropolis (the performance) and NECROPOLIS (the city of the dead). ↑

We consider the choreographic gestures in Necropolis as human-bound and more-than-human-bound. After all, posthuman theory has challenged and rearticulated what the human is, how it moves and how it becomes-with matter, also in performance studies (Stalpaert, van Baarle and Karreman 2021). ↑

Christel Stalpaert

12:40 PM Feb 18

Amade M’Charek and Sara Casartelli suggested establishing relational citizenship for these unacknowledged dead migrants or refugees through forensic care.

Arkadi Zaides

12:42 PM Feb 18

Arkadi: Others such as Thomas Keenan, Dr. Pavlos Pavlidis from the Democritus University Hospital in Alexandroupoli and Cristina Cattaneo from the University of Milan conduct a counter-forensics, turning the active neglect into visibility. ↑

Arkadi Zaides

12:35 PM Feb 18

This play on the word birthright points at the paradox between the formulation of human rights and the fact that these rights are to be preserved in the context of the nation-state. In her discussion of “the right to have rights” in her 1951 book The Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt was concerned with this paradox. People who are stateless are thus always lacking rights.

Also, dead bodies do not have equal rights. As opposed to deaths in armed conflict and humanitarian disaster, migrant deaths do not require systematic identification in Europe. European jurisdiction fails to present an international framework for identification of migrant deaths. A growing number of bodies are labeled as numbers or as nomen nescio and are buried in anonymous graves. This complicates the mourning process of the migrant’s families, who are kept in the dark about the fate of missing relatives. ↑

Arkadi Zaides

4:35 PM Feb 15

Palestine was not labelled on the mapping service of Google Maps. See also https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/aug/10/google-maps-accused-remove-palestine ↑

Critical cartographers, such as John B. Harley, Denis Cosgrove, Jeremy W. Crampton, André L. Mesquita, Chris Perkins and Rob Kitchin, a.o., investigate in a critical manner the ways in which maps reflect and perpetuate relations of power, usually in favor of a society’s dominant group. ↑

Christel Stalpaert

5:34 PM Feb 18

The notion of resurgence attributes the faculty of repairing to ‘dead’ material. The verb ‘to repair’ might still be considered an all too human-centred action. We borrow the concept “resurgence” from anthropologist Anna Tsing (179-192) who describes “persistent resurgence” as “regeneration” (179). To resurge is an intransitive verb: it is characterized by not having or containing a direct object. One can only undergo a resurgence. We deliberately (mis)use the verb ‘to resurge’ in an active way, acknowledging agency in interconnected matter, also in processes of resurgence that are at stake in Necropolis. ↑

Christel Stalpaert

8:20 PM Feb 18

We deliberately use the verb ‘to story’ here, instead of ‘to narrate’, as Haraway’s concept of a vexed place is building on Thom van Dooren’s theory of storytelling, developing “a nonanthropomorphic, nonanthropocentric sense of storied place” (in Haraway, “Staying with the trouble” 39; see also Van Dooren 63-86.) ↑

the Latin tentare refers to the verb to feel. The etymology of the word ‘tentacle’ hence also refers to a tacit ‘production’ of knowledge. The Latin tentaculum refers to ‘feeler’, indicating that the tentacular are not disembodied figures. ↑

Michel Lussault

10:47 AM 13

It might be useful, to enrich the references, to cite here the experiments of Bruno Latour. Latour, in Karlsruhe, has devoted three exhibitions to this question of the staging of thought connected to things (and vice versa). The most recent, Zone critique, in particular, is very interesting.

https://zkm.de/en/zkm.de/en/ausstellung/2020/05/critical-zones/bruno-latour-on-critical-zones

In cooperation with the philosopher Frédérique Ait Touati, he and she also have conceived the performance Viral, where the authors attempt to show on stage the intertwining of humans, non-humans, the living and the dead, things etc…

https://nanterre-amandiers.com/evenement/viral-bruno-latour-frederique-ait-touati/ ↑

This means that students from across the entire university can register for this course, as well as international exchange students. ↑

See: https://fra.europa.eu/en/eu-charter/article/8-protection-personal-data] ↑

In her New Materialist rendering of Anna Tsing’s concept of resurgence, Donna Haraway values art for its “practices for resurgence” (“Staying with the Trouble” 82), and its “speaking resurgence to despair […] in the face of extermination” (“Staying with the Trouble” 71, 76). ↑

Arendt, Hanna. The Origins of Totalitarism. Penguin Books, 2017.

Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations. Translated by Harry Zohn. Schocken Books, 2007.

Besse, Jean-Marc. “Cartographic Fiction.” Literature and Cartography. Theories, Histories, Genres. Edited by Anders Engberg-Pedersen. The MIT Press, 2017, p. 21-43.

Bohm, David. On Dialogue. Routledge, 1996.

Borges, Jorge Luis. “On exactitude in science.” Collected Fictions. Translated by H. Hurley. Penguin Books, 1998, p. 325.

Bosteels, Bruno. “From Text to Territory.” Deleuze and Guattari. New Mappings in Politics, Philosophy, and Culture. Edited by Eleanor Kaufman and Kevin Jon Heller. University of Minnesota Press, 1988.

Butler, Judith. “Bodies That Still Matter.” (lecture, University of Tokyo. December 8, 2018). ( https://youtube.com/watch?v=xiGOw1nfOsU&feature=emb_title )

Crampton, Jeremy. Mapping: A Critical Introduction to Cartography and GIS. Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Graham, Stephan. Vertical: The City from Satellites to Bunkers. Verso Books, 2018.

Haraway, Donna J. “Situated Knowledges. The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial perspective.” Feminist Studies. Volume 14, Issue 3, 1988, p. 575-599.

———. Staying with the Trouble. Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press , 2016.

Ingold, Tim. “Globes and Spheres. The Topology of Environmentalism.” Environmentalism. The View From Anthropology. Edited by K. Milton. London: Routledge, 1993, p. 209-218.

Kotef, Hagar. Movement and the Ordering of Freedom, On Liberal Governments of Mobility. Duke University Press, 2015.

Latour, Bruno. “Anti-Zoom.” Contact, catalogue de l’exposition d’Olafur Eliasson. Fondation Vuitton, 2014, p. 121-124.

——— . “Critical Zones .” An Exhibition at ZKM Karlsruhe 2020. ( https://zkm.de/en/zkm.de/en/ausstellung/2020/05/critical-zones/bruno-latour-on-critical-zones )

Lussault, Michel. “‘Dessiner une terre inconnue’, une géoesthétique de l’anthropocène ,” AOC – Analyse – Opinion – Critique ), Mercredi, 17 juillet 2019.

M’charek, Amade and Sara Casartelli. “Identifying Dead Migrants: Forensic Care Work and Relational Citizenship,” Citizenship Studies. Volume 23, Issue 7, 2019 , p. 738-757.

Macfarlane, Robert. Underland. A Deep Time Journey. Penguin Books, 2019.

Mulder, Arjen. Successtaker. Adrien Turel en de wortels van de creativiteit. Uitgeverij Duizend & Een, 2016.

Noeth, Sandra. Interview with Arkadi Zaides. “Bodies as Evidence. Arkadi Zaides on his Research, People on the Move, and Brutally Closed Borders.” Tia Magazine. 2020, p. 50-53.

Padrón, Ricardo. “Hybrid Maps: Cartography and Literature in Spanish Imperial Expansion, Sixteenth Century.” Literature and Cartography. Theories, Histories, Genres. Edited by Anders Engberg-Pedersen. The MIT Press, 2017, p. 199-218.

Pouillaude, Frédéric. Unworking Choreography: The Notion of the Work in Dance. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Roberts, Les. “Deep Mapping and Spatial Anthropology.” Humanities. Volume 5, Issue 1, 2016, p. 1-7.

Springett, Selina. “Going Deeper or Flatter: Connecting Deep – Mapping, Flat Ontologies and the Democratizing of Knowledge.” Humanities. Volume 4, 2015, p. 623–636.

Stalpaert, Christel. “Choreographic Gestures of Resurgence and Repair: Arkadi Zaides’ research-based performance project Necropolis.” Performance Research. Vol. 26, no. 4, 2021. (thematic issue: On Repair ) – forthcoming.

Stalpaert, Christel, Kristof van Baarle, and Laura Karreman (eds.) Performance and Posthumanism: Staging Prototypes of Composite Bodies. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World. On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins. Princeton University Press, 2015.

Van Dooren, Thom. Flight Ways. Life at the Edge of Extinction. Columbia University Press, 2014.

Zaides, Arkadi. “NECROPOLIS. Walking Through a List of Deaths.” (W)ARCHIVES: Archival Imaginaries, War, and Contemporary Art. Edited by Daniela Agostinho e.a. Sternberg Press, 2021, p. 337-362.