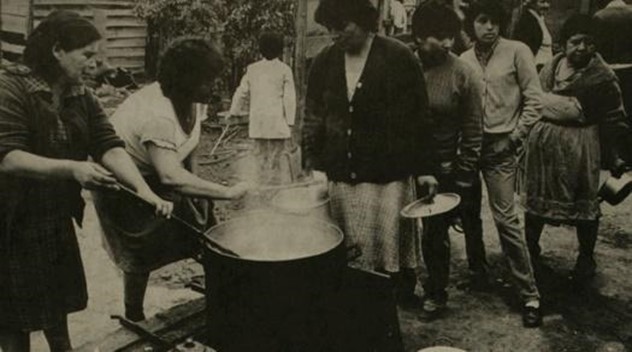

The olla común (common pot) is a traditional form of communitarian activity in Chile but also in other countries in South America, such as the comedores populares in Argentina. It consists of a community meal made entirely by volunteers with food donated or collected by members of the community. It is generally carried out in a public space in the neighborhood, and it has a nourishing but also social role within the community. At different times in the history of Chile, there were situations that led grassroots groups to confront hunger, organizing themselves around ollas comunes in the contexts of earthquakes, political, or sanitary crises. During the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet and again during the COVID-19 pandemic, they became symbols of resistance against oppressive regimes and economic policies. These ollas comunes highlighted the government’s failure to provide for its citizens and mobilized communities to demand better living conditions and rights.

Politics as performance is a key aspect of this article’s hermeneutical approach. We draw on Rai, Gluhovic, Jestrovic, and Saward, who explore two concepts, theatricality and performativity, through which to understand the conceptual complexity of the dynamics of performance in any sphere, but especially in culture or politics. As they write, performativity is not only language-based but also embodied. It is therefore also unpredictable, as stage performance demonstrates (Rai et al.). It is through the performativity of sites, bodies, voices, gestures, and emotions that this article will examine the nature of las ollas comunes. as a repertory of political action in the Chilean context. The relationship between the olla común and performance includes representations of the olla común that are meant as theatricalized or stylized public presentation, which certainly includes performing arts and theatre, but also the theatricality and performativity of actions that are not meant to be fictional or meant for entertainment alone, such as social scenarios in everyday life.

By providing nourishment and fostering social cohesion, the olla común transcends its immediate practical function to become a site of political and cultural significance. We analyze the olla común through the lens of biopolitics, considering how these communal meals operate as tools of resistance and empowerment in times of crisis. The concept of performativity is employed to understand the olla común both “in” performance—where it is represented in a theatrical or stylized manner—and “as” performance—highlighting the everyday theatricality and transformative actions inherent in these communal practices. Post-dictatorship Chilean theatre and art often depict the olla común, emphasizing its role in redefining social norms and identities within a liminal space that challenges conventional structures. The liminal dimension of the olla común allows it to transcend typical social boundaries, fostering solidarity and mutual support. This paper examines how these communal meals facilitate shifts in individual and collective identities, challenging established social hierarchies and promoting new forms of community connection. The ritualistic aspects of the olla común, with shared practices and symbols, further unite communities, serving as expressions of resistance and sources of healing. Ultimately, this study positions the olla común as a powerful biopolitical device, transforming food into a medium of social transformation and political action. By analyzing the olla común through the frameworks of biopolitics and gastropolitics proposed by Appadurai, Montecino and Foerster, and Escobar, we highlight its significance in addressing hunger and fostering resilience in Chilean communities.

The olla común is a traditional form of communitarian activity in Chile but also in other countries in South America. It consists of a community meal made entirely by volunteers, with food donated or collected by community members. It is generally carried out in a public space in the neighbourhood and has a nurturing but also social role within the community. At different times in the history of Chile, there have been situations that have led to grassroots groups to confront hunger, organizing themselves around ollas comunes in the contexts of earthquakes, political, or sanitary crises. We can understand the olla común as a collective food preparation practice, where in most cases the responsibilities associated with the olla común are shared: obtaining ingredients, monetary resources, heating the food (such as with firewood or gas), preparation of food, etc. Another common characteristic has been that of sharing the consumption of food in a collective space, since in general ollas comunes have not been limited to satisfying the task of obtaining food, but have also been constituted as meeting spaces between the community. In Chile, although, logically, the factors that influence the formation of ollas comunes have to do with the lack of basic foods for survival, this also has to do with a threat condition in the face of the real possibility of going hungry.

Historically, the olla común in Chile has quite old antecedents, primarily in rural areas, especially with porotada (beans), a dish that was distributed among seasonal workers or tenants of a farm. The olla común, as it is known today, has its most direct backgrounds in the ollas de los pobres (pots of the poor) of the 1930s, born to face the consequences of the economic crisis. A few years later, this type of survival practice also transformed into a form of protest. By the mid-20th century, it was not uncommon for striking workers to create an olla común as a meeting point, where union meetings and public statements were held, while continuing to fulfil the function of obtaining food for the families of the workers and people on strike. By the 1960s, olla comúnes were frequent in Chile, especially among the emerging movimiento de pobladores or tomas. In the context of Latin America, the term tomas commonly refers to land or building occupations carried out by groups of people claiming property or housing rights. These occupations can be both legal and illegal, and often occur in urban areas where there is a shortage of affordable housing or in rural areas where there are disputes over land rights. The occupations are typically carried out by marginalized or displaced communities seeking solutions to housing, land, or access to basic resources issues. Often, tomas are related to social and political movements seeking to highlight the demands of excluded sectors of society. It was usual during those years that an olla común would be installed in some strategic place in la toma while the plotting of sites was organized and new houses were being constructed. During the civic-military dictatorship after the 1973 coup, we can see an important proliferation of this type of actions, invigorated and supported by the Vicaría de la Solidaridad, a Catholic church solidarity organization. Between 1982 and 1987, when and neoliberalism was imposed in Chile by blood and fire during the Latin American debt crisis, the popular sectors formed an extensive network of subsistence organizations, and ollas comunes were a symbol of the fight for survival.[2]

Due to the strong socio-political weight of this phenomenon, it has not only emerged to solve the problem of access to food but also serves as a form of political action, as an action of denunciation or protest. This is the case of the olla común that was installed in the so-called “Plaza de la Dignidad” during the social unrest of October 2019. In the context of the Chilean social uprising, the ollas communes were back on the street, almost forty years after the Pinochet era. The olla común also made visible the precariousness of an important sector of informal workers who did not qualify for adequate state aid during the pandemic. Generally an olla común is organized by neighbours, usually women, from the local community; however, during the pandemic a new phenomenon was observed. Citizens from other communities who were aware of the proliferation of ollas comunes created a website called La olla de Chile to concentrate all the aid and disseminate the assistance. The citizens’ organization helps 288 ollas comunes from different Chilean regions and works completely digitally. And during the wildfires that swept through Viña del Mar in 2023 in Chile, las ollas comunes played a crucial role in the emergency response. Faced with the devastation caused by the fire, local communities came together to organize community kitchens, providing hot and nutritious meals to displaced individuals and those affected by the disaster. These community initiatives not only served to meet basic food needs but also became gathering points and sources of emotional support for those impacted by the tragedy. Through solidarity and collaboration, las ollas comunes played a pivotal role in promoting resilience and community recovery in the face of the challenges posed by the wildfires.

This reappearance of ollas comunes forces us to consider the political function of these community spaces today. Las ollas comunes represent the concrete necessity of citizens to solve the problem of hunger within the community, but at the same time express a need for the community to stay together in the face of difficulty. They articulate the resolution of citizens to confront the problem of hunger by themselves, in the face of the lack of permanent and consistent government assistance.

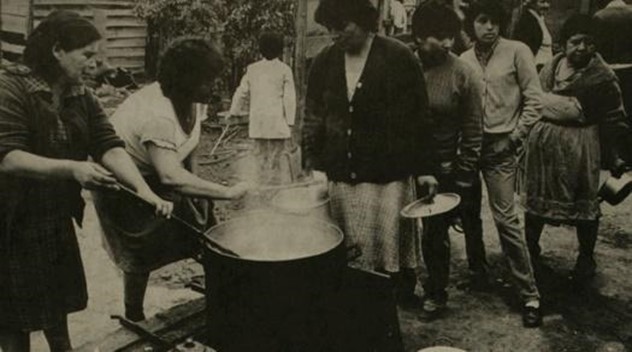

This section explores how the olla común has been represented within the post-dictatorship Chilean theatre and art in two examples: the play La Victoria, written by Gerardo Oettinger and created by the collective Teatro Síntoma, and the documentary La Olla Común (2020), directed by Fabian Andrade and Pamela Cuadros. Through the testimonies of residents who organized and participated against hunger, La Victoria explores how the traditions of the olla común were developed in the context of the dictatorship and economic crisis in Chile in the 1980s. The play takes place in the chapel of a suburb of Santiago de Chile in the months before the first national strike in 1983, when revolution was in the air. The scene begins early in the morning, when the residents enter the chapel and find remains of food thrown on the floor, everything turned upside down, and a broken cross. The play shows how the forces of repression raided the chapel and took the funds collected by the community for the olla común. Despite the violent situation, the residents decide to resist the attack and carry on cooking with the remaining food. The work explores the violence and tragedy that creates ideological and human conflict between the characters, who are all women. La Victoria is inspired by the testimonies of residents who fought, not only against hunger and the military, but also against the lack of understanding of their own people.

In Pinochet’s Chilean dictatorship, the olla común was synonymous with terrorism, and such a communitarian action was prohibited because it was considered a political meeting. Therefore, many residents preferred to go hungry than participate in an olla. Another element to consider in the analysis of the play is gender, as the women struggle to free themselves from the prevailing machismo that, to this day, shapes all social layers. The historic participation of women as organisers of the ollas comunes goes beyond the roles of handling and cooking food, and involves the coordination of family and social life. Women in ollas comunes have played a leading political and social role in the management, organization, collection, preparation, and distribution of food, making these collective spaces a place of political action from the maintenance of life.

The contribution of women in community contexts, of which the ollas comunes are an example, has transformative effects on the consciousness and gender identity of the women who participate. Although the reproductive labor of cooking and serving are allocated to women in traditional gender roles, the ollas comunes place women in the public sphere. For various authors, the participatory experience of women, both in popular social movements and in various grassroots social organizations, not only has important social and political effects but, above all, has cultural effects, as it modifies their conception of being women. Research made in gender and memories studies carried out during the 1980s (Jelin; Campero; Valdés) show that participatory experiences can reproduce the basic binary structure imposed by the gender system between the reproductive-domestic-feminine and the productive-public-masculine. Several studies deal with how these women assumed gendered domestic tasks in the movements or organizations to which they joined, which, although they are vital for their maintenance, did not reach the same notoriety and power as the functions and positions assumed by men. However, it should be noted that the research not only accounts for the reproductive nature of this female participation, but also for its transformative component: “the participation of women in the world of the neighbourhood, originally linked to the satisfaction of the needs reproductive aspects of the family, can have complex and subversive implications for the forms of organization and the traditional order” (Jelin 322). Thus, female socio-political participation acquires more innovative characteristics than might be initially thought: “... the distortion being that female participation is seen as more conservative than it really is; the loss, in not perceiving the ambiguity contained in the participation of women that, despite being done in the name of the most traditional role, represents precisely an exit out of the sphere that is used as a means of legitimization” (Pires do Rio Caldeira 98).

Although women may initiate their participation at the local and community level as a response to the need to care for, protect, and worry about their family nucleus, mainly the children, this initial motivation is also expressed at the level of a concern and motivation for the well-being of their closest community, what Herminia Di Liscia calls the transition from “moral motherhood to social motherhood.” In this way, although there is a certain displacement of the predominant symbolic order, the concern “for the population” or “for the good of others” is identified as a preferably feminine motivation. The care and maintenance of “life” have also been at the centre of the discussion in the context of this current crisis in the 21st century. However, unlike the period between the 1960s and the late 1980s, where the reproductive effect was highlighted with greater force that, today that same participation not only makes it possible to highlight its importance with respect to its transformative role in the impact of gender identity and awareness, but also to highlight its transformative potential regarding the production model and the social system that today seems to be facing a structural crisis.

Another example of the representation of the olla común in Chilean artistic practices is the documentary film La Olla Común, made up of 75 micro-stories recorded during the 2020 pandemic. The documentary offers a non-linear account of the recent awakening of Chilean society. During the Chilean revolt in 2018, the olla común reappeared as a popular organization that emphasises collective work, a supportive spirit, and caring. The film’s directors, Fabian Andrade and Pamela Cuadros, believe that after thirty years of truncated democracy, the insurrection of October 2019 restored hope to a population subjected to authoritarianism. But the state responded in a repressive manner, and human rights violations worsened. Then, the COVID-19 pandemic obligated the communities to carry on with las ollas comunes. The pandemic revealed an uncomfortable conviction: the Chilean model not only produces segregation and poverty, but also hunger.

According to Clarisa Hardy, in comparison with those of the past era of the dictatorship, the organization of las ollas comunes during the revolt and the pandemic has the capacity to assemble much less politically-identifying populations and to develop a more autonomous capacity to tackle hunger and poverty. In this way, they were more politicized and appeared to solve very urgent problems of the economic crisis, but simultaneously they were spaces of struggle for the democratization of the country. Hardy explains that today, ollas comunes are a response to a very urgent social and economic need, but the capacities of those who participate in the territorial organizations developed elements of autonomy that did not exist in the past. For Hardy, this speaks to the strengths of what has been built in these much criticized years of neoliberal democracy, where there was not a great commitment to the social fabric or to the support of organizations, but rather in the acquisition of skills by people. Therefore, part of the strengths or potential of these organizations today is that they do not require an “expert” voice because they have their own internal expertise (Hardy). The territorial expression of the ollas comunes shows a diverse social structure, articulated in institutionalized leadership through communitarian organizations such as neighbourhood associations and functional groups. Likewise, ollas comunes do not have permanent organizations and are activated by various external stimuli. They make it possible to visualize an important social capital that Chilean communities have, despite the adverse context of the extreme neoliberalist development model in which they were born.

This section explores the olla común as “community performance” is its liminal dimension. The concept of liminality was developed by anthropologist Victor Turner and focused on rites of passage. Originating from the Latin word limen, which means boundary, “liminality” is used in anthropology and cultural studies to refer to a state of transition or in-betweenness, where social norms and identities become fluid and questioned. In the context of olla comunes, this transcendence of the conventional boundaries of daily life and established social structures is manifested in several ways. Firstly, ollas comunes often emerge during times of social, economic, or political crisis, when conventional support and governance structures may have weakened or collapsed. As a result, ollas comunes create an alternative social space where norms and social roles can be redefined and challenged, Secondly, as an activity organized by the community and based on solidarity and mutual support, ollas comunes challenge established social hierarchies. In this liminal space, distinctions of class, gender, or other social categories may become less significant, as everyone contributes and benefits equally. Also, participating in the olla común can entail a transformation of individual and community identity. Those accustomed to receiving aid may become donors or volunteers, and vice versa. This transformation can challenge preexisting perceptions of oneself and others, creating new forms of solidarity and community connection. Finally, the olla común may have a ritualistic character, with shared practices and symbols that help unite the community around a common purpose. These rituals can be expressions of resistance, affirmation of identity, or forms of healing in times of crisis. In this way, the liminal dimension of ollas comunes implies that they go beyond being simply community-feeding activities. They are spaces and practices that challenge established social norms, creating opportunities for social transformation, solidarity, and resilience in times of crisis.

This liminal dimension of ollas comunes is rooted in their nature as performative practice. Performativity in its broadest sense refers to the power of social and spatial practices to constitute subjects and objects. In performance studies, “performative” can be both a noun and an adjective. The noun indicates a word or sentence that acts. The adjective gives what it adjusts performance-like qualities, such as “performative practices”. We argue that developed the liminal dimension of ollas comunes are performative practices in two different senses. First, as a rite of passage, where the protesters in the revolt share the symbolic “bread”, transforming again food into a political device. Through recollecting food and cooking, it generates an empowering ritual that, like an army gathering strength, invokes the force needed to face the enemy. Literally and symbolically, by eating together the warriors are getting ready for the confrontation with the enemy. For example, its significance as a symbolic scene of the Chilean revolt illustrates the importance of a “nourishing rite” in conflict.

The second dimension refers to the sense of community. Victor Turner explains that the liminal experiences have certain attributes, including the lack of previously established social ranks and the propitiation of communitas; understood as the experience of an exaltation of a sense of community without structures or social status. Following this line of thinking, Cuban researcher, Ileana Diéguez, recovers the term liminality as a methodological lens in the study of scenic and social practices. Diéguez states that by exercising liminality in scenic practices that involve broad participation, it is possible to facilitate citizens’ sense of belonging. The potential of sharing food to generate communitas was fully embodied by the olla común during Chilean protest inviting everyone to take part in the communitas of resistance, regardless of social structures or status. Moreover, the olla común, through its horizontal structure, is itself an invitation to create a more inclusive and democratic community and society.

According to Michel Foucault (The Birth of Biopolitics; Society Must Be Defended), biopolitics is a technique of power and control that emerged with 18th-century liberalism and aims to manage and normalize the social life of populations through a series of procedures designed to monitor, direct, and intervene in aspects such as marriage, disease, sexuality, crime, etc. One of its characteristics is to link biology with the economy to the point of making them inseparable. Biopolitics as an apparatus for controlling political economy is tied to a larger problem related to the emergence of what has been called “governmental management.” This includes a new governmental rationality exercised over the entire population, whose purpose is to quantify, maximize, and shape social groups. Biopolitics as the governance of the life of populations is directly related to the notion of governmentality, a concept that allows Foucault (Society Must Be Defended) to introduce power relations in terms of a microphysics of power on one hand, and on the other, to analyze how individuals are directed and conduct themselves. However, authors like Roberto Esposito (Bíos; “Biological Life and Political Life;” Terms of the Political; Third Person; Comunitá e biopolítica) address biopolitics beyond the political-institutional practices of governmentality to question the relationship between biological life and political life in a broader context. This allows us to think about community actions as forms of resistance to policies that oppress life (thanatopolitics), as well as their capacity to develop practices that operate from the maintenance of life, which Esposito calls affirmative biopolitical practices—understanding this not as a form of power over life, but the power of life itself.

Las ollas comunes can be considered a form of affirmative biopolitics in certain contexts. Affirmative biopolitics refers to political practices aimed at promoting and preserving life rather than controlling or regulating it restrictively. In the case of community kitchens and ollas comunes, these initiatives are examples of how communities organize to collectively and compassionately meet basic food and nutrition needs. Instead of relying solely on governmental institutions or the market, community kitchens represent a form of self-management and mutual care among community members. Additionally, by promoting citizen participation and solidarity, las ollas comunes can contribute to strengthening social bonds and empowering communities to address common challenges. Therefore, in this sense, they can be seen as a manifestation of affirmative biopolitics by actively and collectively promoting life and well-being.

As Clarisa Hardy observed in a study she conducted during the dictatorship, ollas comunes show how neoliberalism “affects inhabitants so severely that, among other impacts, the problem of food arises. But the pot is more than the need to eat, more than just the mere expression of hunger in the popular sectors” (22). Juan Pablo Silva Escobar suggests that, in this sense, the communal pots that have proliferated due to the pandemic can be understood through the concept of gastropolitics. According to Arjun Appadurai, food is not just nutrients, proteins, or vitamins; it is also a semiotic device in which cultural, social, and political relationships are inscribed, where relations of production and cultural exchange take place. Gastropolitics refers to the study or analysis of the political dimensions of food and eating practices. It explores how food intersects with political, social, cultural, and economic factors, and how it influences power dynamics and governance structures. Gastropolitics examines various aspects of food production, distribution, consumption, and regulation, as well as the ways in which food choices and culinary traditions can reflect or challenge political ideologies, identities, and inequalities. This field of study highlights the interconnectedness of food and politics, and how food-related issues can shape and be shaped by broader political processes and systems.

This action constitutes not only a cultural practice fulfilling the function of meeting a basic need but also establishes a gastropolitics that transforms culinary practices, generally associated with the domestic and private space, into a practice that takes the public space and subverts it as a form of struggle and protest. The ollas comunes (and the food prepared there) resonate in the socio-sanitary and political crisis, revealing the semiotic force of food, which, by turning food into a political device animated by specific cultural practices and mobilized within particular social and political contexts, makes food, in its various expressions and functions, both a necessity for the maintenance of life and a political device (a discourse of power or counterpower) (Appadurai). The gastropolitics inscribed in the ollas comunes contribute to signifying the world and making food a cultural system, a system of symbols, categories, and meanings that are in tension and relation with the social, cultural, and political organization of a particular historical context.

Las ollas comunes, as spaces for the repoliticization (Escobar) and reconfiguration of the community, implement actions (food collection, cooking, ration distribution) and a sense of belonging (community, solidarity, and politics) that go beyond being a palliative for hunger, because communal pots “are connected to the various types of mobilizations and forms of struggle that the popular sectors have developed in response to the problem of hunger” (Gallardo 14). Las ollas comunes are articulated as a political action rooted in a community relationship between organized neighbors (Hardy; Mayol). Food, established materially and symbolically as a system of signification, allows us to glimpse the conditions between the countryside and the market, between abundance and scarcity; it allows us to understand the different forms, contexts, and functions that food fulfills in a given society, or it can indicate rank and rivalry, solidarity and community, identity or exclusion, closeness or distance (Appadurai; Geertz; Montecino and Foerster). Consequently, food preparation constitutes a social fact and a form of collective representation imbued with cultural practices that, as Claude Lévi-Strauss suggested, is a metaphorical image of the raw, the cooked, and the rotten in society, embodying a cosmological vision of civilization. Therefore, gastropolitics can be understood “as a process in which food is simultaneously the medium and the message of a conflict” (Montecino and Foerster 144).

Feeding others can be considered a political action due to its impact on power distribution and social justice. In many societies, access to food is closely linked to the unequal distribution of resources and power. Those who control food production, distribution, or access can exert influence and control over others, which has significant political implications. Additionally, in contexts where there is hunger or food scarcity, the act of feeding others can be a way to advocate for social justice and the right to food. It may involve redistributing resources to ensure that everyone has access to adequate and nutritious food, thus challenging existing power structures and promoting more equitable political alternatives. Furthermore, feeding others can also be an expression of solidarity and resistance against unjust systems. In times of crisis or disasters, communities often come together to provide food and mutual support, thereby challenging established norms and advocating for political alternatives. This act of solidarity addresses not only immediate food needs but also serves as a form of resistance against oppression and marginalization. In this sense, feeding others goes beyond a simple humanitarian gesture; it is a political act that can contribute to the struggle for equity, dignity, and human rights in society.

Furthermore, a feminist analysis of the gastropolitics of ollas comunes would highlight how these initiatives become spaces where gender norms are challenged and transformed. Las ollas comunes are sustained and led primarily by women who take on the responsibility of nourishing and feeding the impoverished community. A feminist analysis of las ollas comunes would unravel the complex gender dynamics present in these grassroots initiatives. These are places where alternative forms of care, solidarity, and female empowerment are promoted, underscoring the importance of considering gender dimensions in understanding and assessing community kitchens as political and community practices. On the other hand, a feminist analysis would also examine how ollas comunes address gender inequalities in access to food resources and promote food justice. It would investigate whether these initiatives are adequately responding to the specific needs of women and marginalized communities, and whether gender experiences and perspectives are being taken into account in their design and operation.

The political function of las ollas comunes extends beyond their primary role of providing food, encompassing several key aspects of political significance. First, they serve as a form of resistance and protest against systemic inequalities and governmental policies that fail to address basic human needs. By organizing and distributing food collectively, communities highlight state inadequacies and the impact of neoliberal policies on vulnerable populations, making self-organization a direct challenge to authorities. Additionally, las ollas comunes empower marginalized groups, particularly women, who often lead these initiatives, asserting their right to survival and dignity while fostering solidarity within the community, creating a unified front to demand better conditions and rights.

Moreover, las ollas comunes reclaim public space by moving a traditionally private activity, such as cooking, into public areas. This subverts conventional norms and transforms these spaces into sites of communal care and political engagement. They also facilitate community organization and mobilization by bringing people together to work towards a common goal, fostering collective responsibility and action, which can serve as a foundation for broader political movements and advocacy efforts. Furthermore, the visibility of las ollas comunes raises awareness about issues faced by marginalized communities, drawing attention to the urgent need for food security, economic support, and social services, which can translate into advocacy efforts pushing for policy changes at local and national levels.

In summary, las ollas comunes are a community practice involving the collective preparation and distribution of food to meet the basic nutritional needs of a community, especially in times of economic or social crisis. This practice typically emerges in contexts of poverty, unemployment, or emergency, where resources are scarce and the need for solidarity is high. Essentially, las ollas comunes represent an organized and communal response to adversity, providing not only sustenance but also a sense of belonging and mutual support.

[1] This article is part of the research project ANILLO ATE220035: Género, biopolítica y creación (Gender, biopolitics and creation) Funded by ANID Chile Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo (National Research and Development Agency).

[2] The Latin American debt crisis of 1982 was a significant event that affected several countries in the region and had far-reaching economic, political, and social consequences for many years. It stemmed from a combination of factors including excessive borrowing, rising interest rates, falling commodity prices, and a global recession. Many countries relied heavily on borrowing to finance development projects, but escalating debt-service costs became unsustainable. The crisis led to interventions by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the implementation of structural adjustment policies, sparking social unrest and political turmoil across the region.

Appadurai, Arjun. “Gastro-Politics in Hindu South Asia.” American Ethnologist, vol. 8, no. 3, 1981, pp. 494–511. https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1981.8.3.02a00050

Campero, Guillermo. Entre la sobrevivencia y la acción política: las organizaciones de pobladores en Santiago. ILET, 1987.

Diéguez Caballero, Ileana. Escenarios liminales: Teatralidades, performances y política. ATUEL, 2007.

———. “La práctica artística En Contextos De Dramas Sociales”. Latin American Theatre Review, vol. 45, no. 1, Sept. 2011, pp. 75-94.

Esposito, Roberto. “Biological Life and Political Life.” Contemporary Italian Political Philosophy, edited and translated by Antonio Calcagno, SUNY Press, 2015, pp. 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781438458540-003

Esposito, Roberto. Bíos: Biopolitics and Philosophy. Translated by Timothy C. Campbell, University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

———. Comunitá e biopolítica. Mímesis, 2012.

———. Terms of the Political: Community, Immunity, Biopolitics. Translated by Rhiannon Noel Welch, Fordham University Press, 2012.

———. Third Person: Politics of Life and Philosophy of the Impersonal. Translated by Zakiya Hanafi, Polity Press, 2012.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1978–1979. Edited by Michel Senellart, Translated by Graham Burchell, Picador, 2010.

———. Society Must Be Defended: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1975–76. Edited by Mauro Bertani and Alessandro Fontano, Translated by David Macey, Picador, 2003.

Gallardo, Bernarda. El redescubrimiento del carácter social del problema del hambre: las ollas comunes. Programa FLACSO, 1985.

Geertz, Clifford. The Interpretation of Cultures. Basic Books, 1973.

Hardy, Carisa. Hambre más dignidad, igual ollas comunes. PET, 1986.

Herminia Di Liscia, María. “Género y Memorias.” La Aljaba, vol. 11, 2007, pp. 141–66.

Jelin, Elizabeth, editor. Ciudadanía e Identidad: Las Mujeres En Los Movimientos Sociales Latino-Americanos. UNRISD (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development), 1987.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude. “The Culinary Triangle.” 1966. Food and Culture, edited by Carole Counihan, Penny van Esterik, and Alice Julier, 4th edn, Routledge, 2017, pp. 21–28.

Mayol, Alberto. El derrumbe del modelo: la crisis de la economía de mercado en el Chile contemporáneo. Editorial LOM, 2012.

Montecino Aguirre, Sonia, and Rolf Foerster González. “Identidades En Tensión: Devenir de Una Etno y Gastropolítica En Isla de Pascua.” Universum (Talca), vol. 27, no. 1, 2012, pp. 143–66. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-23762012000100008

Pires do Rio Caldeira, Teresa. “Mujeres, Cotidianeidad y Política.” Ciudadanía e Identidad: Las Mujeres En Los Movimientos Sociales Latino-Americanos, edited by Elizabeth Jelin, UNRISD (United Nations Research Institute for Social Development), 1987.

Rai, Shirin, Milija Gluhovic, Silvija Jestrovic, and Michael Saward, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Politics and Performance. Oxford University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190863456.001.0001

Silva Escobar, Juan Pablo. “Biopolítica, necropolítica y pandemia. Notas sobre el neoliberalismo y la desigualdad social en Chile.” Autoctonía: Revista de Ciencias Sociales e Historia, vol. 5, no. 2, 2021, pp. 438-53, https://doi.org/10.23854/autoc.v5i2.221

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Cornell University Press, 1966.

Valdés, Teresa. De Lo Social a Lo Político la Acción de Las Mujeres Latinoamericanas. LOM Ediciones, 2000.