The photo of the young woman in the news article on my screen, showing her torso and head propped up, leaning against a large pillow covered in a plaid pattern of blue, gray, and light purple lines against a white background, performs as a visual oxymoron. The studium (Barthes 26–27) of the photo is her big bright smile, shining across her face, and the lively light in her eyes. Here is a portrait of a happily smiling woman. She is wearing a crew neck, cable knit sweater in cheery tones of dark reddish pink. Her cuffs are pulled up to her elbows. Her earrings and red and green wrist bands complement her sweater and her reddish-brown hair, parted on one side and pulled together behind her head. Her neck is covered with a material wrapped around it—if this piece of wrapping too shared the colors of her hair or accessories, or the texture of her sweater, I might have thought she was wearing a turtleneck sweater. But the foam material gives away her fragility. At only 33.8 kilograms (74.5 pounds) in this photo (CNN Türk), and nearly six feet tall, she needs this brace to hold her head up over her frame. The punctum (Barthes 26–27) of the photo, the element that pierces me, is her right forearm. She is holding it up diagonally, her arm bent at the elbow, her hand reaching the right side of her face, her fingers, bent at the knuckles, touching her face. Because it is attached to her hand and her body, I know that this section of her arm between her wrist bands and elbow is not bare bone. But it might as well be, her skin coats the lines of her right ulna and radius bones like thin leather wrapped on the flat cover of a book. Without an ounce of flesh on it, her skeletal body looks almost without life. The hope and joy in her smile and eyes, in extreme contrast with the rest of her, soothe my heart aching at the sight of her disappearing body.

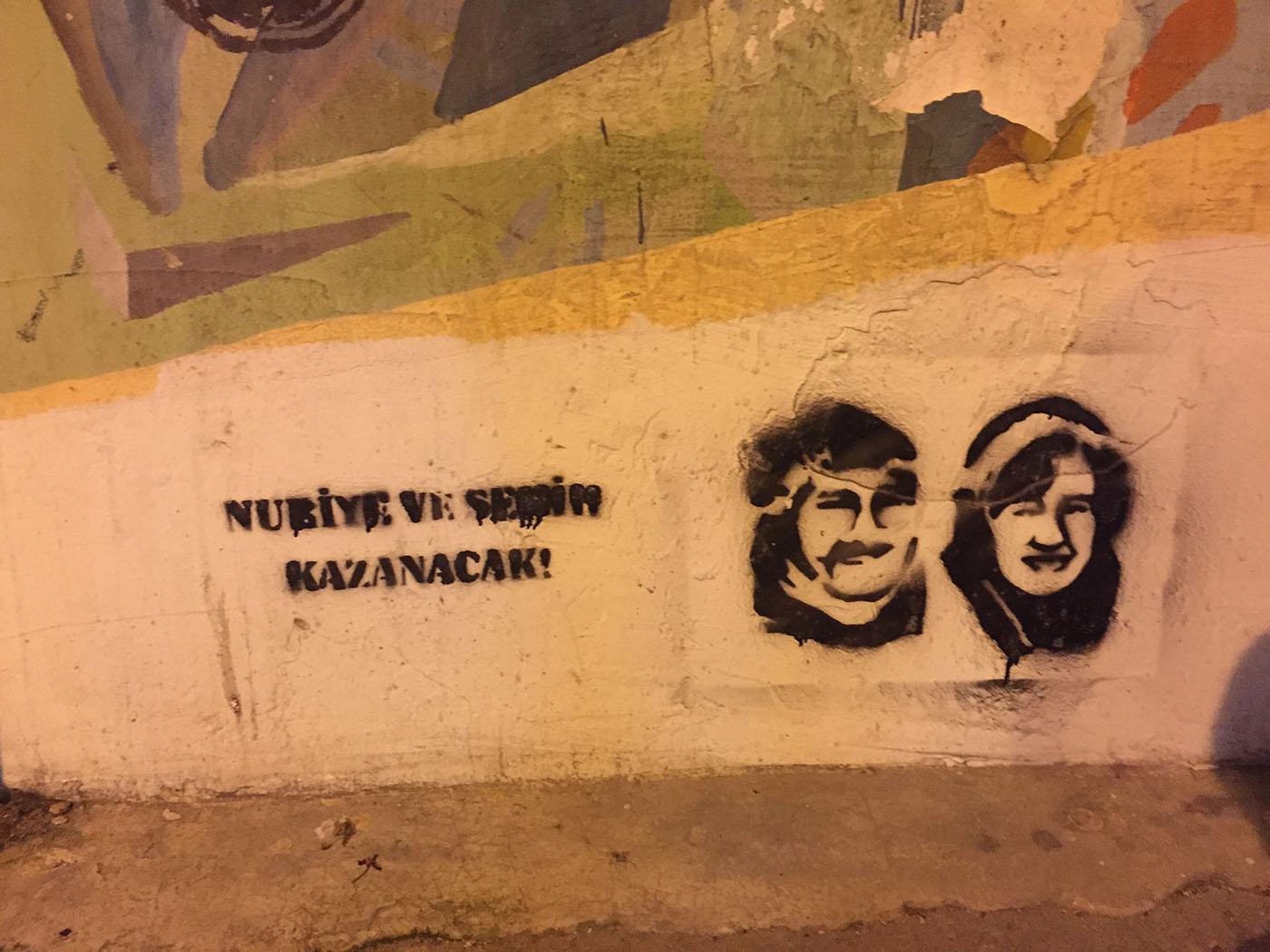

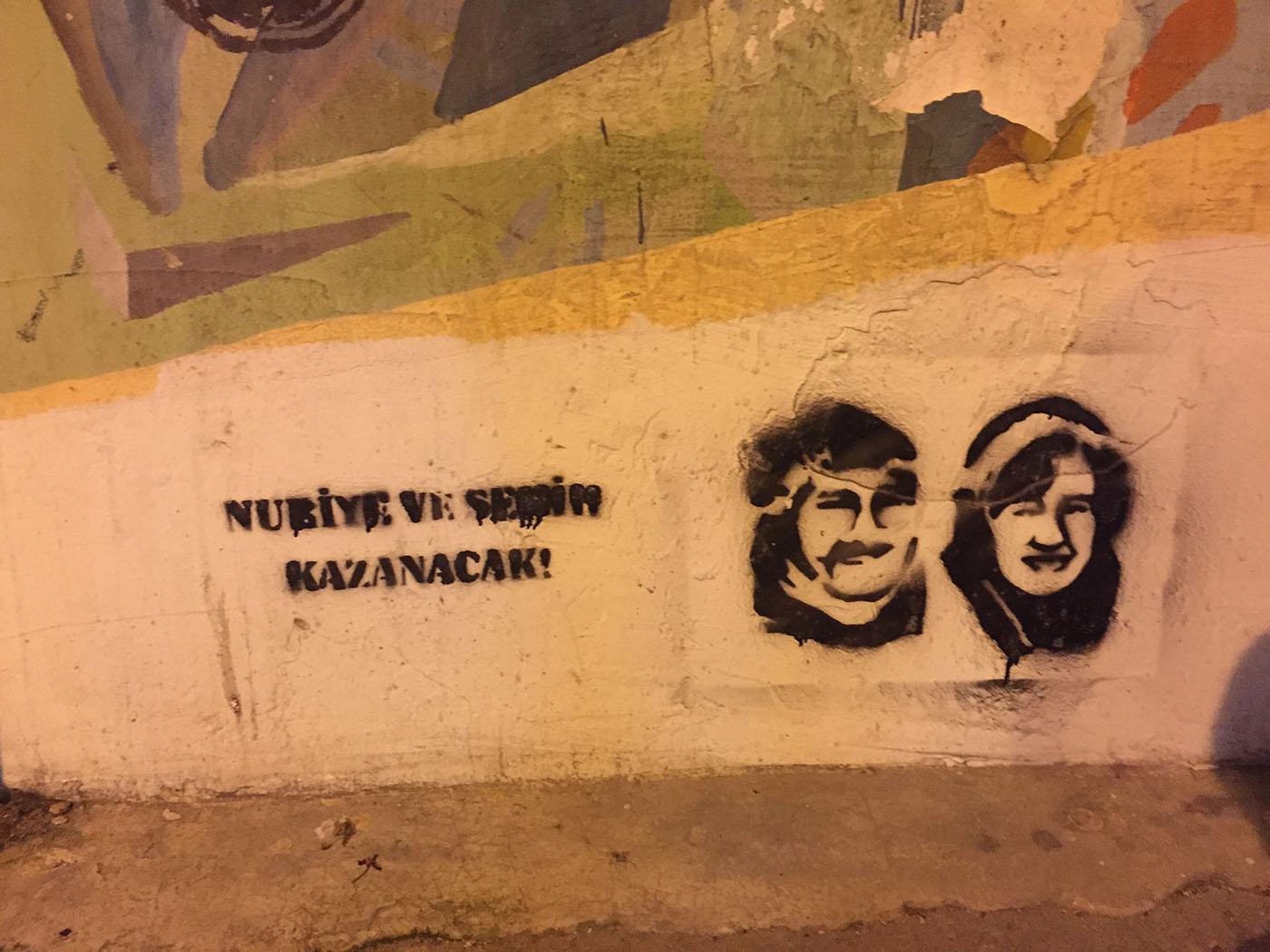

This photo shows academic Nuriye Gülmen on the 316th day of her hunger strike. She and Semih Özakça, a teacher, started this endurance and durational protest performance following another long-term durational protest they performed together. Prior to resorting to the hunger strike, they brought recognition to their plight through an act of civil disobedience—sitting in silent protest with a sign that said “I want my job back” in front of the Human Rights monument in the center of Ankara, the capital city of Turkey for four months. They were detained numerous times during their sit-in protest. They, along with tens of thousands of other public employees, had lost their jobs during a government purge in 2016 following the coup attempt in 2015 (see Deutsche Welle, “Trial Starts for Turkish Teachers on Hunger Strike”). Semih Özakça’s[1] wife Esra joined their hunger strike after two and a half months. On this date in January 2018, after nearly a year of hunger, all three had lost half their body weight and lost their health. Their hopeful smiles remained.

In this article, I discuss how criminalized educator activists in Turkey perform hunger strikes to fight for their right to make a living. I trace hunger visible in the images of the disappearing bodies as a performative (Austin) in the silent and still protest of these university and public-school teachers whose careers were ended due to political retaliation by the institution,[2] the performance is what affectively takes place the moment the viewer is looking at the photographs. Performing hunger serves as a disidentification strategy (Muñoz) for the already starved minoritized groups in exceptional environments such as prisons and refugee camps, resisting violations of their rights. My broader body of work contextualizes the blatant human rights violations governments legally approve, administrators practice, and the public observes. For instance, I previously wrote about hunger strikes by refugees effectively imprisoned in detention centers on islands off Australia by the Australian state (Erincin, “Regarding the Pain of ‘the Other’”). This article too highlights the cruelty of such violations happening not in lawless terrains but those that happen as a result of systemic, approved, and legal policies of majoritarian institutions. Hunger strikes function as performatives to expose such systemic structures which oppress, marginalize, and dehumanize minoritized individuals and groups as protestors resort to this political action only in the absence of any other means of expression for dissent or resistance.

In my performances, installations, and writing at the nexus of social justice and stories of marginalized and minoritized identities,[3] I contemplate the psychophysical implications of lack of fundamental necessities caused by withholding of company, sleep, rest, food, water, movement, and agency. Whether such lack is imposed on bodyminds[4] by torture, protest due to oppression, or experimentation, it creates deprivation and hunger for breath, rest, nutrition, contact—nourishment and healing not just for the physical body but for the entire self. The effects of such physiological lack are always social, emotional, and mental. The mark of such hunger remains on the mind even when the body heals. Like air, shelter, and water, food is a fundamental human right—and it has been widely evidenced that the planet has enough resources for all (Leng). However, states and institutions use the slow violence of hunger to perform power and practice control over others, often minoritized, impoverished communities of color or disadvantaged countries.

Protestors subvert the dynamics of control hunger provides by claiming agency of their own bodies revealing the connection between corporeal and metaphorical agency of the body/self—often those resorting to hunger strike have no agency over their lives except, to a certain extent, what they do or do not do with their bodies. The institutions which profit from the labor of the bodies they discipline and regulate effectively colonize them. Whether in prisons or oppressive state institutions, the body needs to be fed, nourished, and continue to labor for the benefit and according to the will of the institution. When on hunger strike, protestors decolonize their bodies and gain agency over their labor. However, this route of decolonizing the body has dire consequences.

I did not eat any fish between the ages of thirteen and seventeen, once I had control over what I chose to eat. I have many memories from when I was a child of sitting at the dinner table with a bite of food in my mouth, held between cheek and teeth, when I did not want to eat what my parents wanted me to. They could not force it down my throat and I would sit as long as it took, several times a week, in refusal to eat the fish my mom thought would make me smart. I did this because I had no power to otherwise leave the table. The only agency I had was to not swallow the bite I was forced to eat. Research shows it is common for kids to refuse to eat, swallow, and even go to the bathroom when they feel a lack of independence, to assert autonomy over their bodily functions. Research similarly shows that at the root of eating disorders (e.g., anorexia nervosa) also lies an urge to claim agency when one feels they have no control over their life (Colle et al.). Unfortunately, hunger strikes infantilize and pathologize the protestors like children or those suffering from mental illness, socially and physically. They become sick and dependent on care and the state intervenes harshly, penalizing them. The protestors claim some agency over what happens to their bodies, but many lose consciousness and some their lives. This agency controls only their will to die.

Hunger strikes, like other collective protests, have generated ways of being and worldmaking for minoritized groups—despite their destructive outcomes for those who sacrifice their bodies, health, and sometimes lives to enact them. These protests shine light on the violent practices of the state and expose its necropolitical tendencies– the incarcerated protestors would rather risk death than bear the violent practices. Also, by publicly refusing food, hunger strike protestors challenge the legitimacy of the state’s power to decide who lives and who dies through what I call necroresistance[5]. They bring attention to the injustices, human rights violations, and oppressive policies that may result in the loss of life or the devaluation of certain lives through this enduring protest which slowly kills them. However, most writing on hunger strikes groups the form of protest as civil disobedience, often theorizing and analyzing it as a peaceful strategy for nonviolent resistance.

Such writing generates discussions that intersect concepts significant to performance studies and protest performance, such as resistance, civil disobedience, power, agency, ethics, and justice. Philosophers and political theorists contemplating ethics and the body since the prevalence of existential thought in the midcentury have contemplated pushing the body to extreme states in relation to these concepts. Self-imposed bodily practices, such as fasting or hunger strikes, can be argued to demonstrate acts of defiance against disciplinary power and as ways to contest biopolitical control over the body (Foucault, Discipline and Punish). This is the immediate outcome of Nuriye Gülmen’s performance: one can instantaneously identify her defiance against the disciplinary power of the state through performing agency over what happens to her body. She refuses to conform to the dictates of an oppressive system and consequent circumstances. The concept of bare life and state of exception (Agamben) also informs the examination of the power dynamics involved in hunger strikes, particularly in carceral contexts, where individuals reduce themselves to a state of bare life in order to challenge and expose the mechanisms of sovereign power. Similarly, discussion of the psychological and symbolic dimensions of protest in the context of colonialism and resistance (Fanon) could be used to show how Nuriye Gülmen’s performance can serve as an act of defiance and as a way for her to assert her humanity and demand justice.

However, there is a cost. The consequences of hunger strikes are nonreversible. Whether they result in the death or the lifelong ailments of the protestors, it’s an extreme methodology which I consider violent, contrary to their traditional categorization within nonviolent protest. In other words, in this article, while I show that hunger strikes are effective in asserting agency for minoritized and disenfranchised individuals, and share aspects with civil disobedience and peaceful protests through silent and still mobilization of one’s body, I also show why such forms of necroresistance do not belong within the genealogies of nonviolent protest. These methods serve to help performers of the protest effectively decolonize their bodies by defying the state’s necropower.[6] However, I also argue that the means to this end are not nonviolent and they only exceptionally achieve outcomes similar to those of nonviolent protests of civil disobedience.

Most critical writing on hunger strikes engage the concepts and theorists I referred to earlier, and others, through an analysis of mostly contemporary sites of protest (for instance Ajour). Many have detailed the international genealogy of hunger strikes tracing the earliest influential movements from Ireland to India (see, for instance, Miller). In the next section, I will provide a brief genealogy of these protests in the context of Turkey—Nuriye Gülmen and Semih Özakça’s performance joins this genealogy. Their protest, its effect as well as infelicitous outcomes, cannot be interpreted independent of the performatives which have emerged as part of the acts that are part of this genealogy.

Several groups and individuals in Turkey have performed hunger strikes as a means of silent and still protest, since mid-century when Turkey’s most prominent poet Nazim Hikmet was incarcerated,[7] but especially since the violent military coup in 1980, as necroresistance.[8] Nuriye Gülmen and Semih Özakça’s durational performance immediately joined this repertoire of a certain tradition of resistance protests in Turkey. Their choice of protest, the not doing, and tool of choice, their bodies, have become performatives in the country. When the public observe a hunger strike which they immediately understand through the images of the disappearing bodies, they know that the actors, most likely criminalized or delegitimized if not already incarcerated, are protesting political policy and legislation which has had consequences for the protestors’ lives and livelihood—they make these performances that shift between life and death because the stakes are so high. Through their silent and still act of disobedience, the performers of hunger strikes draw attention to a range of local yet globally relevant issues, including human rights violations, political repression, and the treatment of incarcerated individuals. Most resort to this means of painful and lethal protest performance to resist utter subjugation to institutional powers which robs them of agency over their lives. In the absence of the ability to do anything, the not-doing becomes a performative act, the sole attempt at a chance to undo oppressive acts. Nuriye Gülmen, for instance, first fought through legal action, then through a nonviolent sit-in protest, before she and Semih Özakça eventually resorted to the hunger strike, which later became a death fast.

Hunger strikes in Turkey became internationally resonant as a social issue without being associated with a significant figure such as Gandhi or Bobby Sands, in the years following the bloody coup of 1980, named after the day it struck, September 12th. Since then, nearly two hundred people have died during hunger strikes related to political imprisonment in Turkey. In 1982, a group of leftist political prisoners launched the act in Diyarbakir Prison. Though this was not the first act of hunger strike in Turkey, nor was it the first one in this prison—in April 1981, Ali Erek had died when a piece of bread tore his esophagus during a forced feeding—it was the first one that had become part of the national agenda. Six protesters, suffering from antidemocratic policies of the post-coup period, announced they were beginning a hunger strike during their appearance in court on 14 July, demanding improved prison conditions, fair trials, and an end to torture. The strike drew significant attention to human rights abuses of the military regime. Between days 55 and 65 of the strike, four of the protestors died.

Soon after, on 28 May, 1984, 400 incarcerated protestors started a hunger strike in the Metris and Sağmalcılar prisons. They made four demands: an end to uniform clothing, end to torture, the right to political arrest, and improvement of social and humane conditions. The act became a death fast after 45 days followed by a number of deaths in June—the protestors no longer consumed the sugar and salt with fluids.[9] The act put the prison conditions on the public agenda again. In early 1986, the policy of uniform clothing was terminated. Around 2,500 people in prisons joined country-wide hunger strikes in 1996, demanding the government abandon its plans for prisons with F-type (isolated), cells. Over nine days twelve people died. Writers and artists mediated with the government and the strikes ended. In December 2000, protestors in eighteen prisons coordinated a mass hunger strike demanding the abolition of the collaboration to establish F-type prisons among several units of the government and the anti-terrorism law which would further oppress political prisoners. The action turned into a death fast on the 45th day. A military operation to end the strike, called Return to Life, had violent consequences.[10] Thousands more incarcerated people have joined hunger strikes in the past couple of decades.

Other groups and individuals beyond the confines of prisons also performed hunger strikes in Turkey. For instance, in 1996, a group of coal miners against the privatization of state-owned coal mines in Zonguldak, a province on northwest Turkey, went on hunger strike. Their demands for job security, improved working conditions, and the payment of overdue wages gained significant public support and lasted for several weeks, eventually leading to negotiations and concessions from the government. This was a rare incidence of positive outcomes for the protestors. This is possibly because the miners, unlike incarcerated protestors requesting better conditions or ousted academics like Nuriye Gülmen demanding their jobs back, were not criminalized and their actions did not directly protest a specific, and overtly politicized, action of the state. In other cases, minoritized politicians initiated hunger strikes to protest oppressive government policies, without success. In Turkey, hunger strikes such as these served to highlight social and political issues and bring them to the forefront of public and governmental attention. However, they nearly never achieve success in having the protestors’ requests met.

My focus on the paradoxical nature of hunger strikes—protestors cause harm to themselves to effectively demand end to institutional harm—intersects with philosophical questions of the moral complexities and implications of such acts of self-imposed suffering. As such, in this article, I take a different stance than most others who have written about hunger strikes in the context of nonviolent or peaceful resistance. For instance, Hannah Arendt’s discussion of civil disobedience and political action in On Violence and The Human Condition argues that hunger strikes perform as a means for individuals to express their dissent and engage in moral and political dialogue. Similarly, Gene Sharp considers hunger strikes among methods of nonviolent action that can generate moral pressure, disrupt systems, and mobilize support for social and political change. Other thinkers’ writings on resistance and political thought have informed contemporary interpretations of hunger strikes in various places such as Guantanamo and Palestine.[11] Judith Butler’s work on ethics, resistance, and the politics of nonviolence within the context of political agency (Frames of War) informs analyses of the embodied nature of hunger strikes and show how these protests can challenge norms, disrupt power structures, and draw attention to social injustices. Patrick Anderson, in his book So Much Wasted: Hunger, Performance, and the Morbidity of Resistance (2010), analyzes self-starvation within the contexts of medical, artistic, and social sites including hunger strikes in Turkish prisons and also engages with Louis Althusser and Martin Heidegger’s ideas on sovereignty. As Anderson also writes, invoking Peggy Phelan’s theories on the ontology of performance, hunger strikes serve as sites of analysis as embodied live performances of political subjectivity that challenge institutional sovereignty.

While I agree with these writers that hunger strikes function to mobilize protestors’ agency, I do not consider hunger strikes or death fasts[12] to be nonviolent means of protest, despite their shared aspects with civil disobedience and affinity with peaceful, silent, and still protest. It is accurate that the protestors do not directly harm others and that the objective of their protest is reached through a lack of action—not eating. However, they do hurt themselves. Is a suicide bomber’s protest considered to be nonviolent if no other individual is hurt as they blow themselves up? A hunger strike or death fast is just as violent, yet the violence is slow. I do not think a single life purposefully lost or willingly sacrificed is worth any of the achieved gains. The value of one’s life cannot be quantified: arguments for the efficacy of such performances—suggesting the loss of life has made progress or betterment of conditions achievable—dangerously perpetuate principles of martyrdom, sacrifice, and corporeal punishment. And the violence amounts to much more than the number of those who perish. Perhaps only a small percentage of those who go on these durational performances of protest die during the term of the act; however most continue to suffer severe lifelong ailments.[13] Much of the damage of a hunger strike or death fast cannot be reversed—even in cases of continuous medical supervision, careful consideration, and support from legal and advocacy organizations to ensure the safety and well-being of the participants. Hunger strikes do not disrupt systems through the methods of nonviolent protest. Hunger protests are violent. The scene is one of death: they are performances of slow death and dying. And even when self-inflicted, violence remains violence. As such, I want to be clear that while this article aspires to bring visibility to the plight of oppressed individuals and groups who resort to this method of protest (in this case educators in Turkey), I do not in any way mean to glorify hunger strike or death fast performances. Hunger strikes can be effective because they expose the systemic oppression in legal structures. Sometimes, but rarely, they force these systems to enact change in order to end the strike and evade responsibility for any deaths. As performances of necroresistance, they share many elements with certain performance art, making claims to agency, bodily autonomy, sovereignty. However, such claims are at the expense of death: the performers claim the agency to die.

In the beginning of this article, I described the haunting of Nuriye Gülmen’s image of bare bones and skin, and a smile, to capture the affective power of the image of the performer’s body—showing the starvation, the threat of death, as it eats itself alive, and the resilience. In Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag writes about the power of photographs in validating the presence of atrocities. “Narratives can make us understand,” she writes. “Photographs do something else: they haunt us” (90). Through data in news or stories, we cognitively understand the facts of the violence suffered by individuals. But through visual documents of those suffering in concentration camps, slow genocide, war zones, we realize what they experience through embodied performances.

In the same book, Sontag debates her own ideas about the power of images in mobilizing protest. She notes that the protests against the war in Vietnam or the genocide in Bosnia were influenced by the photographs and footage in the media. Writing even before the ubiquity of social media, she also notes that in a world “hyper-saturated with images, those that should matter have a diminishing effect: we become callous. In the end such images just make us a little less able to feel, to have our conscience pricked” (104). Although they seemingly contradict the ideas in the immediately preceding paragraph, her criticisms are accurate. Without the images, the chances of outcry or solidarity with those suffering is less likely; and yet, people have become callous to images of suffering—the dead, bloodied, and the wounded, hurting, crying, devastated people. Many turn their heads away from such images or are unaffected.

However, images of people, otherwise not wounded, deliberately disappearing their bodies, outside of war zones, make a statement of both the suffering and the protest. When combined with the smiling, resilient eyes full of light and life contradicting the rest of the frail body, Nuriye Gülmen’s image is the protest, the event, the performance itself calling for wider action. The loss of flesh and the absence of any mass in the skeletal bodies of the protestors covered in their skin evidences the protest of the hunger strike, performing resilience, pain, loss, and resistance. The smile and the light in the eyes perform agency, sovereignty, and resistance to being a subject, a material belonging of the institution. The protest generates its public influence through the photographs disseminated in news and social media which document the willing disappearance of life through the bodies of the protestors and the resilience permanent in their facial expressions. The performance happens in these photographs. The spectators experience the protest, the event, through them; the performance is what affectively takes place the moment the viewer is looking at the photograph. I argue that the elements of the photograph generate the effect of Gülmen’s performance, establishing the severity of institutional oppression. As such, the documentation of the slow disappearance of her flesh in the images is essential to the effects of this protest performance. The recognition of a hunger strike in the emaciated body of the performer immediately shows the viewer that this is a scene of political protest, one in which the individual and the state fight over the sovereignty of the life and death of the individual.

Concepts of necropower and necropolitics from Achille Mbembe, perhaps the most influential contemporary thinker on engaging with this topic, bring light to the location of resistance, agency, and sovereignty in the protest of Nuriye Gülmen and other criminalized or incarcerated individuals. In his influential work Necropolitics, Mbembe explores the intersection of power, sovereignty, and the control of life and death within contemporary political systems. Mbembe defines necropolitics, or necropower (92), as a form of power that operates through the control and manipulation of mortality and the ability to dictate who can live and who must die. He expands on the concept of biopolitics and biopower (66), coined by Michel Foucault (The Birth of Biopolitics), which focuses on the management of life, by examining the mechanisms and practices that govern death and the conditions under which certain lives are considered disposable or expendable. Mbembe examines how necropolitics operates through various mechanisms, including state violence, surveillance, and the control of populations. He explores how certain populations are subjected to systematic violence, oppression, and forms of social death, often driven by racial, ethnic, or political considerations, exercised through the deliberate infliction of death or the creation of conditions that lead to mass death. Most significant for the purposes of this article is Mbembe’s analysis of zones of exception and necropolitical spaces. In these spaces, such as detention centers, refugee camps, prisons, or occupied territories, the normal laws and protections that govern life and death are suspended. The state exercises absolute power over life and death.

Mbembe also highlights forms of resistance and the potential for the reclamation of life and agency. He explores how communities and individuals can challenge and subvert necropolitical systems by creating alternative forms of life, fostering solidarity, and reimagining possibilities for existence beyond dominant power structures. Even within the confines of prisons, lacking any physical energy to move, hunger strike activists find strength in solidarity with others and enact means for feeling freedom. Was this the strength, the claiming of agency in the protestors’ disappearing, decolonized bodies, that intimidated the authorities so deeply that every time they intervened, using disproportional power and cruel means to end the protestors’ confined protests? Why was a young woman, not even able to support her neck above her shoulders, still seen as a threat alive or dead? The relationship between hunger strikes and necropolitics lies in the intersection of power, resistance, and the control of life and death and decoloniality’s threat to fascist practices. In fact, my claim that these protests are not non-violent further asserts my argument about the power of the protests to decolonize the body, as the ultimate agency the protestors assert, the agency over their own lies, defies the state’s necropolitical power.

Hunger strikes and death fasts subvert the power dynamics of necropolitics by protestors who willingly put their lives at risk—performing agency over their own lives and necroresistance. Hunger strikes also perform biopolitical resistance against the mechanisms of necropolitics. By refusing to eat, individuals such as Nuriye Gülmen reject the systems that attempt to control and regulate their bodies, particularly when it comes to issues such as political repression, human rights abuses, or social injustice. The individual act, recognized through the performative of the image of the disappearing body, becomes a social movement. Hunger strikes disrupt the normal functioning of biopolitical control and assert the inherent value and dignity of life.

Nuriye Gülmen’s protest performance garnered support and solidarity from numerous individuals, organizations, and communities within Turkey and internationally. Academics, activists, human rights organizations, students, and ordinary citizens rallied around her cause, joining protests, staging demonstrations, and organizing campaigns to raise awareness about her situation and the broader issues she represented. Her protest drew extensive media coverage, both within Turkey and globally. News outlets reported on her protest, raising awareness of her demands, the reasons behind her ensuing hunger strike, and the broader issues of academic freedom and human rights. This media attention further highlighted the connection between mainstream politics and the global challenges and pressure critical or activist academics face.

Nuriye Gülmen’s hunger strike and the attention it received played a role in the legal proceedings surrounding her case. Her arrest and detention, along with the conditions leading to her hunger strike, drew international criticism and seemingly increased pressure on the Turkish government to address her situation. Advocacy groups and human rights organizations called for her release and the protection of academic freedom, contributing to the broader dialogue on human rights in Turkey. However, the state responded to Nuriye Gülmen’s hunger strike and the ensuing international pressure by arresting her, along with Semih Özakça, and charging them with membership in a terrorist organization. This prompted further international criticism and calls for their release. Human rights organizations, foreign governments, and academic institutions expressed concern over her situation and the erosion of academic freedom in the country. This international pressure contributed to the visibility of her case and the broader issues it represented. However, she continued to face legal proceedings and was charged with severe crimes, which she and her supporters vehemently denied. The charges against her were related to her participation in protests and her alleged affiliation with left-wing groups (see Deutsche Welle, “Turkey Frees Academic on Hunger Strike). In March 2018, Nuriye Gülmen was convicted by a Turkish court for membership in a terrorist organization and sentenced to six years and three months in prison. The conviction also was widely criticized by human rights organizations and supporters who saw it as an infringement on freedom of expression and a politically motivated decision. Following her conviction, Nuriye Gülmen appealed the verdict.

Nuriye Gülmen’s bodily protest serves as a rich site of performance analysis at the intersection of biopolitics and the body, human rights and academic freedom, gender and activism, and state repression and control. Her body is the site of her resistance protest, and her hunger strike challenges the state’s control over her body, especially after her incarceration. Her protest performance also drew international attention to the human rights violations and restrictions on academic freedom—especially the increasing lack of agency that scholars and educators have at universities with regard to curriculum, instruction, and the overall constrictions on free speech. (While Nuriye Gülmen is located in Turkey, this concern is not limited to that country; academics worldwide routinely get penalized for their dissenting opinions.) Her protest performs the implications for activist scholars and intellectuals of the erosion of democratic institutions and the stifling of dissent. Her embodied performance at the intersection of gender and activism shows how her identity as an activist woman in academia complicates the broader implications for women’s rights and gender dynamics globally. Her activist performance and the ensuing institutional response of repression, arrests, and eventual charges of terrorism perform the implications for freedom of expression, the criminalization of dissent, and the broader political climate for activists in majoritarian institutions and show how they get threatened or delegitimized when confronting issues with the processes of the institution—the state or the university.

However, I would like to close by observing that Nuriye Gülmen’s previous nonviolent sit-in protest in front of the Human Rights Monument in Ankara, a sculpture depicting a woman reading the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, had already been powerful, without eroding half her body. In 2016, she had already been elected one of eight leading women by CNN for her sit-in protests (Ghitis) despite being arrested over thirty times. The power of this peaceful protest in front of the Human Rights Monument, in the four months before she and Semih Özakça added the hunger strike to the protest, was so threatening that access to the immediate area of the monument was blocked for a year (Kingsley). With the hunger protest, Nuriye performed agency over her body, her will, her fate. A year later, she and Semih Özakça ended the strike declaring they would fight through legal channels. As of May 2023, Nuriye is incarcerated in the Marmara prison, sentenced to ten years. Rather than sacrificing an ounce of her flesh or health to institutional oppression, I wish Nuriye had continued to find other sites to perform her peaceful and powerful sit-in protest to this day, even after the original site of that protest was made inaccessible, without responding through self-violence.

[1] The public widely refer to the protestors as Nuriye and Semih, by their first names. As it matters to utter their first names, throughout the article I use their full name whenever I refer to them.

[2] See the details of the process documented by Scholars at Risk Network.

[3] For a discussion of the work at the intersection of such margins as radical rhetoric see Erincin, “Fictocriticism, Futurity, and Critical Imagination: Writing Stories as Activism,” and Erincin, “Performing hope at hopelessness: radical rhetorics, critical states, vulnerable populations.”

[4] “… that is, my mind and body as an integrated, interdependent, and inseparable unit, a whole psycho-physical entity acting together wherein the processes of one are tied to and effect the other; in other words, this term recognizes that the often separated mental and physical processes are interconnected and that the function of one—for example, the brain—is not superior to the other—for example, the body” (Erincin, “Decolonizing Identity in Performance” 186).

[5] When I first thought of this concept and coined it built on Achilles Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics, I was not yet aware of others who also used it in. Some of these uses such as Banu Bargu’s conceptualization of necroresistance as “the self-destructive practices that forge life into a weapon as a specific modality of resistance” (27) is closely related to my use. Others such as Sheilla L. Rodriguez Madera who considers it as “the ways in which trans people defy the threats imposed by necropraxis through “ordinary” acts manifested in their everyday life” use it in related contexts though expanding on different meanings.

[6] For an analysis of other forms of embodied means of decolonial performance methods see Erincin, “Decolonizing Identity in Performance.”

[7] In 1950, on May 9th, newspapers in Turkey reported the words of artist Celile, the mother of Turkey’s most significant, internationally renowned poet and playwright, Nazim Hikmet Ran. She announced she was joining her son, who had been found guilty of instigating the army to rebellion, in hunger strike, calling for his release from prison. The next day, prominent Turkish poets Orhan Veli, Melih Cevdet, and Oktay Rıfat joined her. Nazim Hikmet Ran, sentenced to twenty-eight years and four months of incarceration for acts that did not qualify as crimes in 1938 (Toprak 11), had gone on the hunger strike during the thirteenth year of his term, on April 8th, 1950. Upon requests of his lawyer, he paused his protest performance on April 23rd, and restarted on May 1st. He was hospitalized on May 13th and ended the protest on May 19th. His protest galvanized activists and intellectuals. They campaigned for his release drawing international attention followed by similar protests abroad. Shortly after, he was released as part of a general amnesty.

[8] For a discussion of this coup referred to as “September 12th” and its consequences see the introduction to Erincin, Solum and Other Plays from Turkey . For additional analysis about some of the plays that are in this anthology and contextualized in the introduction, see Erincin, “15th Istanbul International Festival.”

[9] See Murat Sevinç’s engagement with medical ethics and the Turkish penal code on the subject.

[10] See Patrick Anderson’s chapter “to lie down to death for days” in his book So Much Wasted for an international perspective and performative analysis of the 2000 strikes.

[11] See the work of contemporary political theorists such as Banu Bargu and Lisa Guenther.

[12] Hunger strikes and death fasts are philosophically similar but have few significant differences. Though not always, death fasts follow hunger strikes when the latter bring about no change or results. Protestors resort to these methods of corporeal performance when they feel they have no other means of expression. They both involve withholding of nutrition. However, a person on hunger strike sustains their bodies with vitamins or other caloric fluids intake such as water mixed with sugar. A person on a death fast, however, refuses any nutrition and only drinks enough water to not lose consciousness. According to Süleyman Özar, who wrote for the Union of Turkish Bar Association’s Review, death fasts should be considered as a variation of hunger strikes (3–4).

[13] The physical and biological harms of starvation become immediately evident and have been well documented, especially as medical professionals often become involved in effort to keep those on hunger strike alive. Long term studies on survivors of holocaust and those who have taken part in restrictive eating studies also show that the psychological changes are severe and often irreversible when people remain deprived of nourishment. See Sharman Apt Russell’s “The Hunger Experiment” for further documentation on the psychophysical effects of starvation.

Agamben, Giorgio. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Translated by Daniel Heller-Roazen. Stanford University Press, 1998.

Ajour, Ashjan. Reclaiming Humanity in Palestinian Hunger Strikes: Revolutionary Subjectivity and Decolonizing the Body. Palgrave Macmillan, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88199-3

Anderson, Patrick. So Much Wasted: Hunger, Performance, and the Morbidity of Resistance. Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822393290

Arendt, Hannah. The Human Condition. The University of Chicago Press, 1958.

———. On Violence. Harcourt, 1970.

Austin, J.L. How to Do Things With Words. Oxford University Press, 1975. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198245537.001.0001

Bargu, Banu. Starve and Immolate: The Politics of Human Weapons. Columbia University Press, 2014.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. Hill and Wang, 1996.

Beynon, Joe. “Hunger strike in Turkish prisons.” The Lancet, vol. 348, no. 9029, 1996, p. 737. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)65605-X

Butler, Judith. Frames of War: When is Life Grievable? Verso, 2009.

Colle, Livia, Dize Hilviu, Monica Boggio, et al. “Abnormal Sense of Agency in Eating Disorders.” Scientific Reports vol. 13, 2003, article 14176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-41345-5

CNN Türk. “Ankara Tabip Odası’ndan Nuriye ve Semih açıklaması: Gidişattan kaygılıyız.” CNN Türk, 19 Jan. 2018. https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/ankara-tabip-odasindan-nuriye-ve-semih-aciklamasi-gidisattan-kaygiliyiz

Deutsche Welle. “Turkey Frees Academic on Hunger Strike.” DW, 2 December 2017. https://www.dw.com/en/turkey-hunger-strike-academic-given-conditional-release/a-41623117

———. ”Trial Starts for Turkish Teachers on Hunger Strike.” DW, 14 September 2017 https://www.dw.com/en/trial-of-two-turkish-teachers-on-hunger-strike-starts-amid-protests-and-tear-gas/a-40515920

Erincin, Serap. “15th International Istanbul Theatre Festival.” Theatre Journal, vol. 59, no. 2, 2007, pp. 296-299. https://doi.org/10.1353/tj.2007.0107

———. “Decolonizing Identity in Performance: Claiming My Mother Tongue in Suppression of Absence.” Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 41, no. 1, 2020, pp. 179–95. https://doi.org/10.5250/fronjwomestud.41.1.0179

———. “Fictocriticism, Futurity, and Critical Imagination: Writing Stories as Activism.” Communication and Critical/Cultural Studies, vol. 18, no. 3, 2021, pp. 342–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/14791420.2021.1960693

———. “Performing Hope at Hopelessness: Radical Rhetorics, Critical States, Vulnerable Populations.” Quarterly Journal of Speech, vol. 110, no. 2, 2024, pp. 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2024.2334390

———. “Regarding the Pain of ‘the Other’: Performing Home in Diaspora and the Politics of Transdiasporic Identity.” The Routledge Handbook of Ethnicity and Race in Communication, edited by Bernadette Marie Calafell and Shinsuke Eguchi, pp. 284–298. Routledge, 2023. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367748586-27

———. Solum and Other Plays from Turkey. Seagull/University of Chicago Press, 2011.

Fanon, Franz. The Wretched of the Earth. Grove Press, 1963.

Foucault, Michel. The Birth of Biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège De France 1978–1979. Picador, 2010.

———. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Penguin, 1979.

Guenther, Lisa. “Political Action at the End of the World: Hannah Arendt and the California Prison Hunger Strikes.” Canadian Journal of Human Rights, vol. 4, 2015, pp. 33–56.

Ghitis, Frida. “8 leading women (and one girl) of 2016.” CNN, 26 December 2016. https://edition.cnn.com/2016/12/26/opinions/women-of-2016-ghitis/index.html

Gülmen, Nuriye. Twitter profile. https://x.com/nuriyegulmen?lang=en

Kingsley, Patrick. “In Turkey, a Hunger Strike Divides a Country in Turmoil.” The New York Times, 1 June 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/02/world/europe/turkey-hunger-strike-erdogan.html

Leng, Ratanak. “Can we feed the world and ensure no one goes hungry?” UN News, 3 October 2019. https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/10/1048452

Mbembe, Achille. Necropolitics. Translated by Steve Corcoran. Duke University Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1131298

Miller, Ian. A History of Force Feeding: Hunger Strikes, Prisons and Medical Ethics, 1909–1974. Palgrave, 2016.

Muñoz, José Esteban. Disidentifications: Queers of Color and the Performance of Politics. University of Minnesota Press, 1999.

Özar, Süleyman. “Etik ile Hukuk Sarkacında Açlık Grevi” (Hunger Strikes in the Pendulum of Ethic and Law). Türkiye Barolar Birliği Dergisi (Union of Turkish Bar Associations Review), vol. 34, issue 154, 2021, pp. 1–41.

Rodríguez Madera, Sheilla L. “From Necropraxis to Necroresistance: Transgender Experiences in Latin America.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence, vol. 37, no. 11–12, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520980393

Russell, Sharman Apt. “The Hunger Experiment.” The Wilson Quarterly, vol. 29, no. 3 2005, pp. 66–82

Scholars at Risk Network. “Date of Incident: August 08, 2018.” https://www.scholarsatrisk.org/report/2018-08-08-unaffiliated/

Sevinç, Murat. “Hunger Strikes in Turkey.” Human Rights Quarterly, vol. 30, no. 3, 2008, pp. 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1353/hrq.0.0018

Sharp, Gene. Methods of Nonviolent Action. Porter Sargent, 1973.

Sontag, Susan. Regarding the Pain of Others. Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2003.

Söylemez, Ayça. “Nuriye Gülmen: I Could At Least See The Sun in Prison.” Bianet, 17 October 2017. https://bianet.org/haber/nuriye-gulmen-i-could-at-least-see-the-sun-in-prison-190668

Toprak, Zafer. “Nâzım Hikmet’in Açlık Grevi – Mayıs 1950.” Toplumsal Tarih, no. 77, 14 May 1950, pp. 9-13.