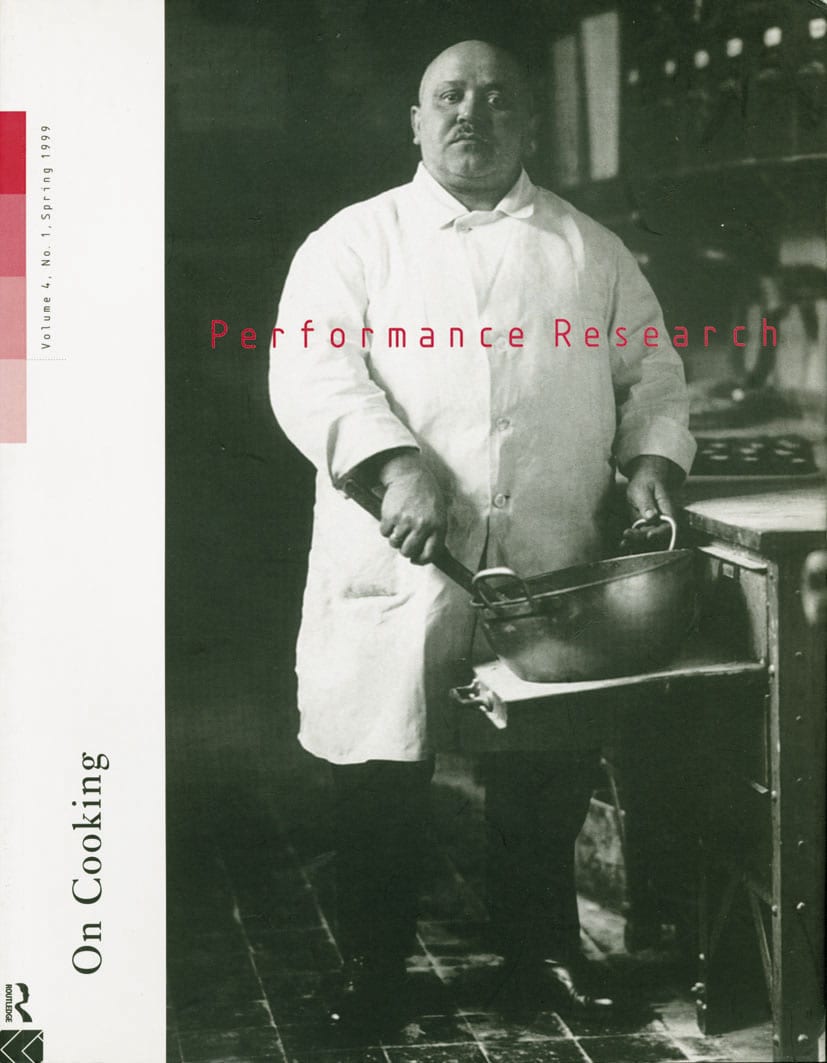

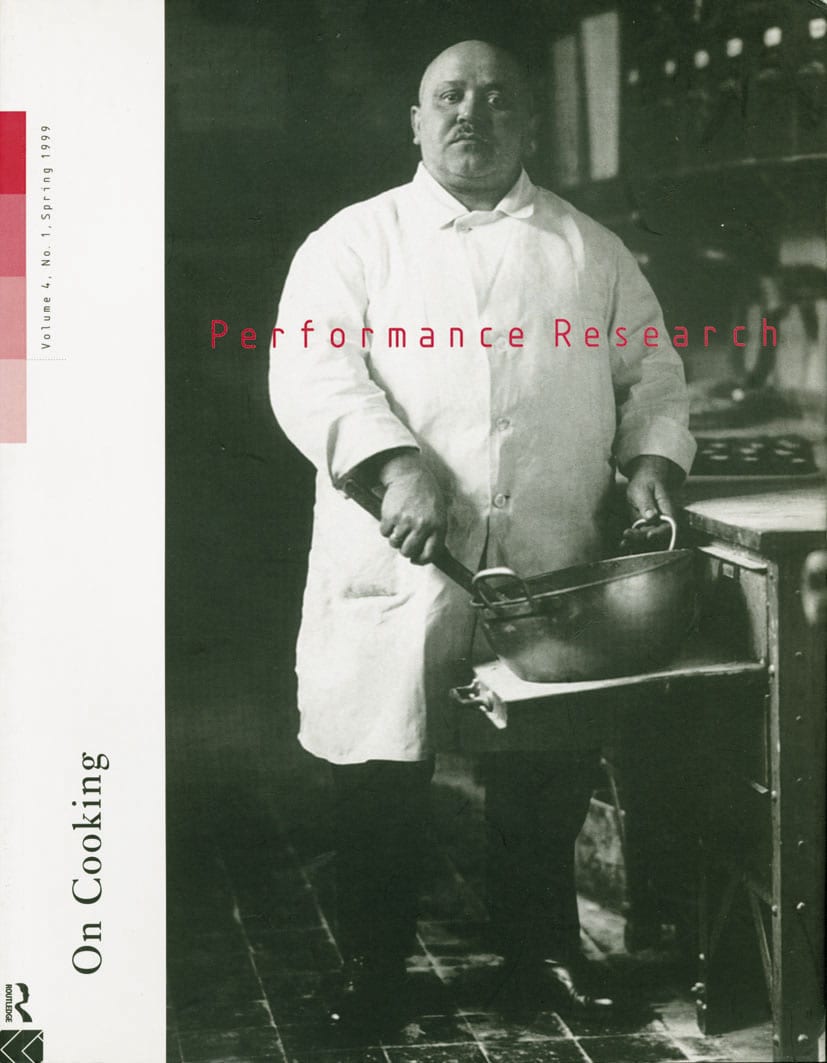

In December 2020 Jazmin Llana, already in the process of planning the twenty-seventh Performance Studies international conference (PSi #27: 2022) contacted me as she wished to begin a discussion around the theme of hunger. She was interested to know how I had explored hunger within the Centre for Performance Research’s international conference Points of Contact: Performance, food and cookery that I had organized more than a quarter of a century before, in Cardiff.[1] She had noticed that in the editorial to the Performance Research issue On Cooking (vol. 4, no. 1, Spring 1999) that arose from and responded to the conference, I had reflected on the need for an entire other issue themed “On Hunger”, responding to the concerns Enzo Cozzi had raised at the conference and throughout the five years until the publication of On Cooking. This is the paragraph from the editorial:

From the outset of this project, Enzo Cozzi was quick to remind me that whilst some of us may be affluent enough to indulge in gastronomic pleasures or indeed play with our food, for others it is a political issue and a matter of survival. This led to research on famine, hunger, food disorders, the hunger strike as a political act and force-feeding and the withholding of food as punishment and torture. Indeed, the material for an entire other issue. It is necessary, profound and timely that Enzo's article on hunger should appear within the body of this issue, and it strikes a resonant and haunting chord. (Gough iv)

The themes explored at the CPR Performance, Food and Cookery conference and the connections made between ideas, people, processes, and cuisines have continued to inspire and nourish me. I remain fascinated with food and performance, food in performance, and food as performance: with the process of cooking and making theatre; with presentations at the table and on the stage; with the creative fervour of the kitchen and the rehearsal room; and with the very material of food as a medium for performance and as a model of performance: multisensory, processual, and communal. The conference explored the piquant analogies and correlations between the processes in cooking and performance, but it also included presentations (papers and productions) on food disorders, fasting, hunger artists, hunger strikes, famine, and radical hospitality, issues that I will take up again in the following article (that is based upon the keynote I delivered at the PSi #27 conference and for which an element of spoken and performed delivery has been retained).

Llana had also been particularly moved by Cozzi’s essay “Hunger and the Future of Performance” that formed a part of the PR journal issue On Cooking. It begins with an unusual retelling of the Stone Soup story, that appears more prosaically in many folk traditions of Europe. I will end my own essay with a more optimistic version, as a call for change and action, but let us first confront the pessimistic as evoked in Cozzi’s entwining of hunger and the future of performance: “The end of this story is unclear. But it is possible that the man died of starvation in pursuit of the perfect performance and the perfect meal.”

Llana was adamant from the outset and resolutely clear in her curation of PSi #27: Hunger that the conference should directly address the theme of hunger. It was not to be taken metaphorically, as desire, longing, or yearning—or for what performance might be hungry for, or in need of. In an early “concept note” she wrote: “The theme is Hunger and we mean real, physical hunger, and we hope the CFP [call for proposals] is written in a way that would communicate this and prevent any easy slippage into metaphor.”

A non-metaphorical engagement of hunger through the optic of performance studies is a real, urgent, and difficult challenge. Cozzi’s article problematizes the issue of representation; hunger cannot be represented. He states: “Hunger is the pressing presence to an organism of the absence of sustenance (of whatever kind).” The difficulty to re-present hunger it seems to me is the impossibility for performance to adequately, or effectively to engage with it. But it is also a problem for the imagination. Hunger is too real, graphic, too present, pervasive, and unassailable.

Despite several unsuccessful attempts to contact Cozzi in 2021, to invite him to present at PSi #27: Hunger we eventually reconnected with him and obtained his permission (and that of PR publisher: Routledge), to republish, in full, his 1999 article. This facsimile forms the first part of this section.

Change in food systems is not only possible, it is necessary; for the people, for the planet and for prosperity […] Food is a human right, not just a commodity to be traded.

António Guterres, Secretary General, United Nations, 2021

From the outset the difference between hunger and starvation needs to be clarified. Hunger is nuanced and multifarious; starvation is absolute and uncompromising. The relation between the two is complex. The curator of PSi #27: Hunger and now the editorial team of the journal issues arising from the international conference have been explicit and categoric; hunger is not to be apprehended as metaphor. They insisted that

physical hunger and efforts to combat it must remain present in any effective performance studies approach to the topic, but to understand how hunger is produced, reproduced and represented in the world we must also grasp how “actual hunger” is imbricated in desires and motivations that are not reducible to biological nutrition. (Call for Proposals GPS and PR)

However, there are positive, healthy, transformative, and celebratory aspects to hunger. Fasting, temperance, abstemiousness, moderation, measured nourishment, the breaking of fast, and commensality are all grounded in hunger. But starvation is void of hope or salvation—and most often wholly avoidable. The downward spiral from hunger to starvation to famine needs to be uppermost in our minds as we struggle with issues of representation, hunger, and the future of performance and avoid any indulgence in the “Starving Artist”. As Cozzi reflected in the previous article: “from the perspective of those dying of starvation, this world is already ending every day, apocalypse is now.”

In a book published thirty years ago by Virago in partnership with Oxfam—Loaves & Wishes: Writers writing on food—Germaine Greer, one of twenty contributors, wrote a short text entitled “Famine”. She reflected on her travels in Ethiopia in the mid-1980s and how the people of the Wollo were having to eat saltless European Economic Community (EEC) flour pancakes. She appositely highlights the difference between hunger and starvation.

“If they’re that hungry” said the man from the American relief organisation, “they’ll eat anything.” He was wrong, of course. Hunger is the best sauce only until it turns into starvation. Starving people are not hungry. Starving people have no appetite at all. Hunger is healthy; most of us need to feel it far more often than we do […] Starvation is sickness in mind and body. To be dying of hunger is to have failed everything and everyone; to watch the people you love growing more ghastly and skeletal day by day is mental torture of the most exquisite. (Greer 11)

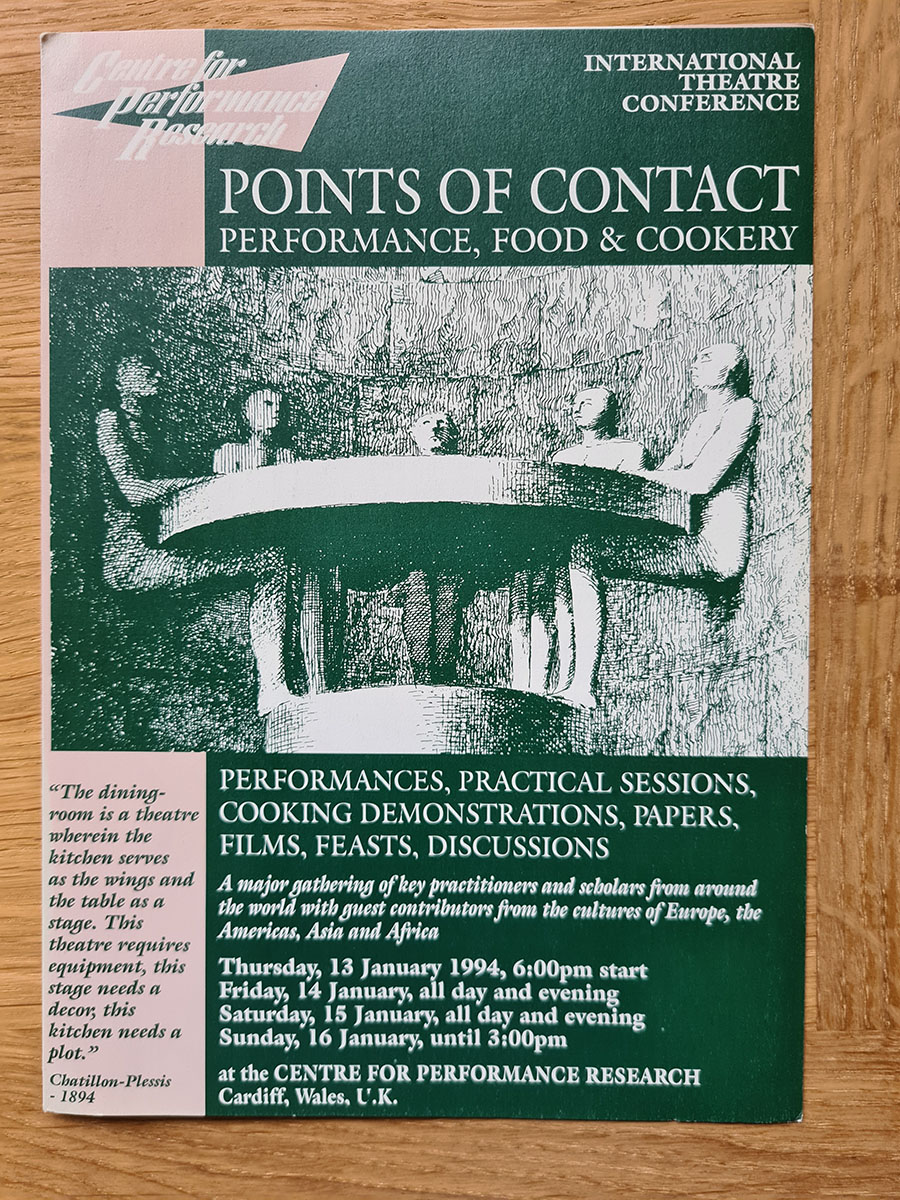

Anyone reading this essay over 60 years old will recall the deeply disturbing images (film and photographic) of the famine in Biafra, that began in late 1967 and was sustained for three years. The Nigerian government deliberately starved its own people in one of the bloodiest civil wars of independence perpetrated in Africa. Hunger was a weapon of war. One million people died, with possibly up to 10,000 people dying of starvation every day, most of them children. The British photojournalist Don McCullin (1935–), known for his war photographs and images that searingly capture conflict and urban strife (Cyprus, Congo, Vietnam, Palestine, Northern Ireland in the 1960s and 1970s) travelled to Biafra in 1968 and documented the Biafran Famine. McCullin’s images of orphaned children, emaciated and yet also bloated, were excruciating and yet also arresting, demanding attention. The filmed reports and documentaries that followed shocked the world; it was the first time that starving children were shown on television.

“Think of the starving children in Biafra,” my mother used to say to me as I left some pie crust or green vegetable on my plate, and many parents around the world likewise chastised their privileged children. And I tried to imagine, but it was hard, unappealing, and counterproductive. What could I do? How could I help? And at the same time the images disturbed the comfort of home as they pervaded teatime television and then on the evening news just before going to bed. It was the stuff of nightmares, but I could not begin to imagine what it must have been like for the children of Biafra. Hunger is not about being peckish; hunger, turning to starvation, is when the body begins to eat itself and the mind fragments. The famine in Biafra, like all famines, was the result of war and political manoeuvres; the Nigerian government cut off food supplies to the partially recognized secessionist state of Eastern Nigeria that declared independence as the Republic of Biafra (1967–70). We only need to think of Afghanistan, Haiti, Yemen, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, Mali, North Korea, and Somalia today.[2] What was so shocking to the Western eye about Biafra was the televisual and photographic images. They burned the retina. They scarred the imagination. And what was so confusing for a child, like me, was the distended and bloated stomachs (looking as if grossly obese), caused by the disease kwashiorkor, a result of severe protein malnutrition.

These images resonate today. They are obscene, as from the Latin obscaenus: ill-omened or abominable. Is it their graphic portrayal of the real, their harrowing presence and agonizing presentation of the unimaginable, that renders performance or representation inadequate, ineffectual, invalid? In 1936 T. S. Eliot wrote “humankind cannot bear very much reality” (incl page and add publication to refs); now we must navigate through a “heap of broken images”, broken because they are heart wrenching and catastrophic.

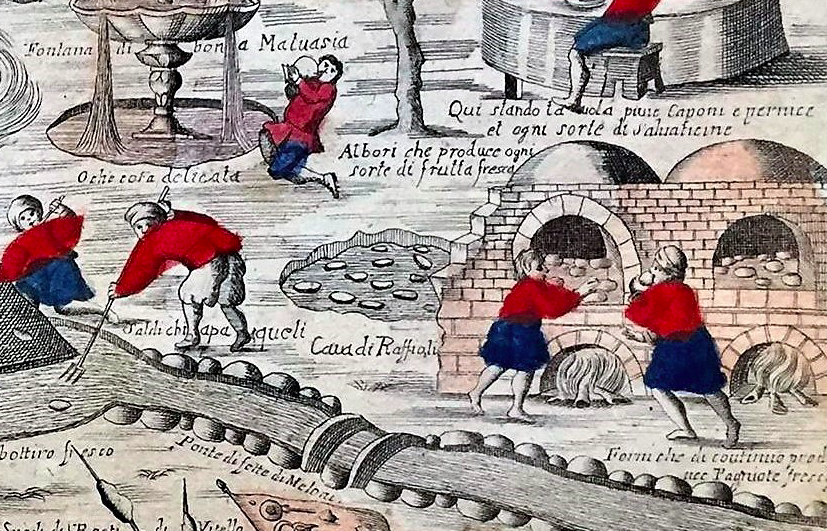

Humanitarian documentation graphically and directly disturbs the onlooker, however, in earlier times of extreme hardship, poverty, food scarcity, and brutality, the collective mind often turned to envisage utopias—so it was in Medieval Europe with the Land of Cockaigne. This the land where, contrary to all reality, rivers flowed with wine, where the sky rained basted plump geese, fish leaped out of the sea ready-cooked, and roasted pigs wandered the earth with knives in their sides willingly surrendering chunks of crisp fatty flesh.

In Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s painting entitled Land of Cockaigne (1567) we see a clerk, a peasant-farmer, and a soldier, satiated and in slumber having gorged themselves of all they could fill—note the egg still wandering, spoon poised to self-serve, and the pig conveniently prepared as a perambulatory street food, the roof of pies and the open-mouthed knight waiting for the next ready meal to fly his way. Here the landscape invites all to over-indulge but through the comic Bruegel points to a spiritual emptiness encouraged by gluttony.

The Land of Cockaigne as a treasure or pleasure island, as paradise on Earth, literally a land of milk and honey appears in poems, paintings, music, and song throughout Medieval Europe. The maps of Cockaigne—Paese della Cuuccagna in Italian, Luilekkerland in Dutch (lazy, gluttonous land)—are perhaps the most poignant cartographies of the imagination. These maps perform and capture the bitter resentment about the hardships of daily life, hard labour, food shortage, and hunger. The longing to satisfy all appetites through a magical transformation of reality (magical realism), enflames the imagination, allegory and parody are interlaced, and seemingly exist without irony or cynicism: simply desire.

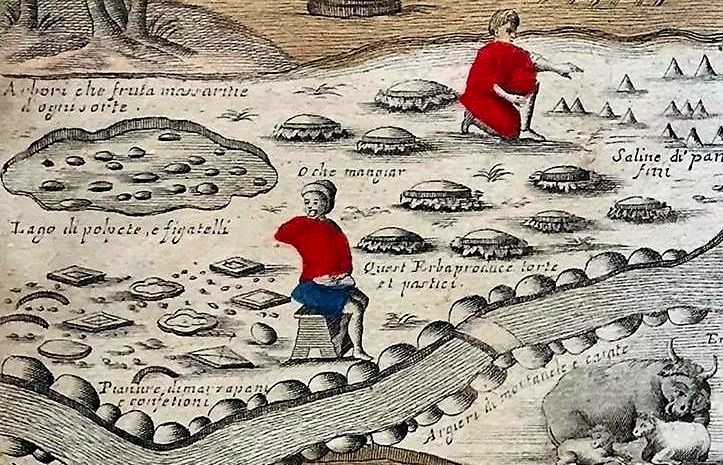

The most direct connection between hunger and performance, in the sense of staging/showing hunger, self-starvation being witnessed in the public arena, with tickets sold and endurance observed, was the bizarre phenomena of the hunger artist prevalent in Europe and North America in the late 1800s. Along with sword swallowers and snake charmers, it was at first a form of sideshow, briefly gaining notoriety and a large public following, only to fall into decline to become a scorned and desolate freak show on the edge of the circus. This fall from grace and loss of public favour is acutely observed in Kafka’s short story “A Hunger Artist”, one of his last texts published in 1922. Kafka begins “A Hunger Artist” by reflecting on the decline of this once noble public entertainment and its diminishing impact in recent decades:

Back then the hunger artist captured the attention of the entire city. From day to day while the fasting lasted, participation increased. Everyone wanted to see the hunger artist at least daily. During the final days there were people with subscription tickets who sat all day in front of the small barred cage. And there were even viewing hours at night, their impact heightened by torchlight. (Kafka, A Hunger Artist and Other Stories)

But even in the decade before Kafka was writing this text there were six hunger artists regularly performing in Berlin, some inside fashionable restaurants, heightening the dramatic tension between the abstemiousness of the caged artist and the satiated flamboyancy of the dinners. This early form of durational performance enjoyed public interest for little more than thirty years, akin perhaps to the 1990s (and onwards) phenomena of bleeding performance artists with self-inflicted wounds. Kafka’s hunger artist continues to perform after the fashion has passed and the story explores themes of isolation, alienation, and disregard. Endurance starvation in its zenith was, however, immensely popular and part of the predominantly male prowess of physical fitness, mountaineering, and boxing. (The hunger artists were not emaciated and weak; rather they were courageous, driven, and determined.)

The athleticism and robust good health of the hunger artists—during their apogee—is in stark contrast to that of Kafka’s when he was preparing the collection of short stories A Hunger Artist (Ein Hungerkünstler) for publication. The laryngeal tuberculosis he suffered worsened in early 1924 and he edited the collection on his deathbed. It was published shortly after his death (3 June 1924). “A Hunger Artist”, as a single short story, had appeared in 1922 in the quarterly publication Die neue Rundschau whose origins were as a theatre journal. Kafka had started writing A Hunger Artist before his throat began to close but during the editing of the collection he was, it transpires, dying of starvation; intravenous feeding (PN: parenteral nutrition) not having been developed at that time. Kafka could not swallow and therefore he could not eat. Towards the end of A Hunger Artist the cage appears empty, but the forgotten and now much derided and disdained performer is crumpled in a heap beneath his straw. His bitter, sad, confession is that he only starved because he could never find food he liked the taste of. He is replaced by a vivacious panther, who devours all the food he is given with abundant delight—the crowds begin to assemble once more to witness a performance of consumption.

Henry Tanner was famous in New York in the 1880s and many admirers paid to witness him perform a forty-day fast. The Italian Giovanni Succi, however, was probably the most famous and believed to be the inspiration for Kafka’s short story. Succi collaborated with physiologist Luigi Luciani and helped reveal much of what we know about the physiology of starvation and its effects on the central nervous system.[3] But he was first and foremost a showman, extending his fasts to thirty and then fifty days and adding horseback rides, gymnastics, and bouts of fencing mid-fast.

The forty-four days fast was often the aspired pinnacle of starvation by hunger artists, and it is perhaps no coincidence that this was the record aimed for by David Blaine, the North American illusionist, magician, and endurance artist, as he sealed himself in a Perspex® box and was hoisted above the River Thames, near to the Tower Bridge in London on 5 September 2003. Blaine endured more than starvation for his art; he was taunted by many onlookers and disbelievers and ridiculed by an antagonistic press. Conspiracy stories were rife speculating that it was all a hoax, and that the water he imbibed was enhanced with glucose and nutrient supplements.

It was a markedly different reception to the hunger artists of 100 years earlier and in stark contrast to the admiration bestowed one year earlier upon the queen of performance art Marina Abramović as she installed herself behind the fourth wall of a three-roomed installation in The House with the Ocean View.[4] As she confidently wrote as part of her artist statement:

If I purify myself without eating for 12 days, any kind of food, just drinking pure water and being in the present moment—that kind of rigorous way of living and purification would do something to change the environment and to change the attitude of people coming to see me. (Moma 2002)

And from the adulation of her adoring public, it would appear most did believe: the artist was present, the artist was sanguine, the artist was blessed.

The point at which endurance starvation, practised by the hunger artist, becomes political and the performance becomes efficacious (with the potential to cause change), is when it takes the form of hunger strike. This form of protest, usually adopted by the imprisoned or incarcerated because little else other than their own bodies is available to them, has been enacted over millennia but became astutely and courageously effective in the twentieth century and continues today.

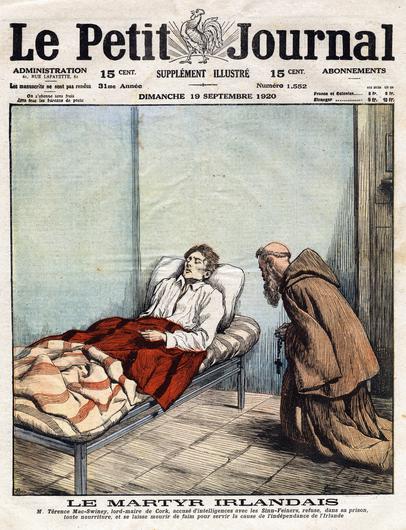

The earliest and most notable hunger striker of more than 100 years ago was neither Terence MacSwiney (the Lord Mayor of Cork) in 1920, nor Mahatma Gandhi (Leader of Indian Independence) who undertook eighteen different fasts from 1913 to 1948; it was Marion Wallace Dunlop (1864–1942), the Scottish artist, author, illustrator, and Suffragette. Better known for her art nouveau illustrations of elves and fairies, she stamped a wall of the House of Commons with a Bill of Rights for Women in indelible ink and was charged with wilful damage. On refusing to pay a fine she was sentenced to one month in Holloway Prison where she petitioned the governor, stating: “I claim the right recognized by all civilized nations that a person imprisoned for a political offence should have first-division treatment; […] I am now refusing all food until this matter is settled to my satisfaction” (Spartacus Education). After ninety-one hours of self-starvation, fearing she might die and become a martyr, she was released, and this heralded an era of hunger strikes within the Suffragettes and especially the Irish Independence Movement from 1916 onwards.

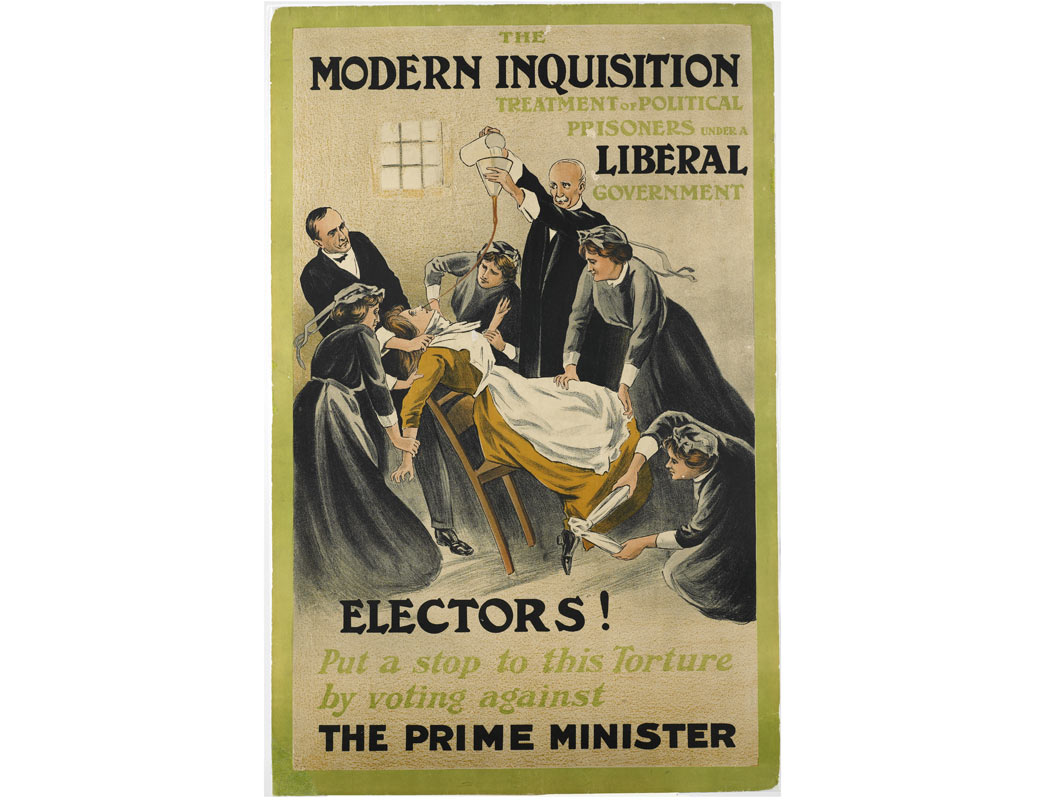

The hunger strike is perhaps the most dangerous, and effective, entanglement of hunger and performance. It elevates the act of the hunger artist as a side show to the main stage, entertainment to education, the fascination of endurance to an apprehension for survival. Although performed unseen and without an audience, the abstemious denial is amplified through media and the subterranean channels of state and government. The clock ticks loudly and the days are publicly charted. Unlike David Blaine, evoking the self-serving hunger artists of a century before, hunger strikers—Emmeline Pankhurst, Bhagat Singh, Cesar Chavez, Irom Chanu Samilla, Bobby Sands, Oleg Sentsov, Lyubov Sobol, Alexei Navalny, the list is long, a roll call of thousands—form a noble chain of unselfish political protesters, who stage their performance in solitary confinement, behind bars, with incremental and unremitting pain. But as a protest and as a self-sacrificing act it gains public attention in ways that the state cannot control. It enflames the imagination (perhaps more so because being unseen). And then we come to the most perverse enfolding of food, hunger, and performance: force feeding.[5] The Suffragettes were subjected to this in the early part of the last century, and it remains the institutional apparatus to enervate and deprive the hunger strike of its political efficacy. Force feeding is brutal and its persecution the absolute nadir of state power against the will of the individual. It erases all dignity of self-starvation.

Almost every nation in the world has a history of hunger strikes causing focused attention on issues of state that the government of the day finds threatening. From the perspective of the UK the history of hunger strikes within Ireland endured by Irish Republicans is especially agonizing, first in the 1920s and then in the 1980s. Within the Irish independence movement, the hunger strike becomes the “protest of last resort”, a chilling and apposite phrase. From 1913 to 1922 there were a dozen hunger strikes connected to the War of Independence and the subsequent Irish Civil War. Several strikers died and perhaps most notoriously Thomas Ashe because of force feeding at Mountjoy Prison (Dublin) in September 1917. As Suffragette Marion Wallace Dunlop had demanded political prisoner status in 1909, so too did many Irish Republicans in 1920, and by April there were 101 internees on hunger strike. Three went to the bitter end and died of starvation, including the Lord Mayor of Cork, Terence MacSwiney.[6]

Many Irish Republicans were incarcerated through a policy of internment and by October 1923 there were more than 5,000 internees on hunger strike. Although not an official policy of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) this dark legacy perhaps explains why hunger striking as an effective form of protest emerged again in 1980 and 1981 in the Maze Prison, Belfast, and elsewhere. Now it was an issue for republicans and members of the IRA in Northern Ireland (almost sixty years since partition) to demand prisoner of war status while imprisoned and the refusal by an inflexible and obdurate Thatcher government. We know too well the result: Bobby Sands died on 5 May 1981 after a sixty-six-day hunger strike, and civil unrest broke out across Ireland. Over the next two months nine other republicans died, triggering the worst period of the “Troubles” in Northern Ireland with scores of civilian deaths. British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher remained intransigent and unsympathetic, announcing in the House of Commons: “Mr. Sands was a convicted criminal. He chose to take his own life.”

It seems an especially cruel twist of history that hunger strikes should so frequently be adopted (from 1920) as a path of protest in a country when less than eighty years earlier famine had ravaged the nation. The Great Famine, also known as the Great Hunger, devastated Ireland (then part of the UK) from 1845 to 1852 and has influenced the formation of the nation of Eire and defined its relationship to mainland Britain ever since. Ostensibly caused by a potato blight but complicated by the dominance of British absentee landlords and over-dependence on a single crop, the famine caused more than one million deaths and more than two million people fled as refugees. I remain conflicted by an opinion the owner of a seafood restaurant in Kinsale, Cork, once gave. He suggested that at the time of the potato famine the rivers of Ireland would have been full of salmon and trout and the coast abundant with sea food—there was plenty of food for the taking. No doubt this was true but how do agrarian citizens reimagine themselves as riparian? How are new techniques for both harvesting food and preparing it rapidly learned? It was a worrying provocation made by this restaurateur, who could trace branches of his family lost to the Great Hunger. But it has always made me think that in times of crisis we need assistance to imagine the unimaginable. In some situations, this is the potential of performance but in the face of hunger and famine is performance impuissant, ineffective?

From the perspective of famine, modern-day fasting may appear as an indulgence or a privilege. As a practice of abstinence it demands the abundance of food and its availability. In previous times (now reoccurring) it was also a way of measuring out meagre supplies. Most religions prescribe a defined period, within a day or as a set number of days, for the individual to wilfully abstain from food (and often all appetites), it being a vehicle to enhance spiritual discipline and self-control. Brought up within a British Christian education I was always curious about the significance and frequency that forty days and forty nights were proclaimed. Moses in the wilderness awaiting commandments, Jesus in the desert being tempted by Satan, the time between resurrection and ascension, and others I can no longer remember. Forty days and forty nights bewitched me, the temptation of Christ and his fasting in the Judean Desert enthralled me. The challenge to turn stones into bread seemed a marvellous one, but the response, “Man shall not live by bread alone,” was incomprehensible to me. Even greater confusion arising when hearing about Christ’s first miracle of feeding the 5,000 that is recorded in all four Gospels: Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John (evinced by our “Religious Instruction” teacher with confirmation that such quadruple iteration indicated absolute truth). After a multitude had gathered and hunger had set in, five loaves and two fish, proffered by a young boy, were broken and transformed into a feast, leaving all satisfied and twelve baskets of leftovers. Turning stones into bread seemed like an easy task compared to this.

Christ’s miracle confounded me as a child. Was it simply magic? Couldn’t this be the solution to Biafra? If anything, the miracle caused me to be sceptical and irritated me for years. As a rebellious teenager at boarding school, for an open discussion with the cathedral bishop, I delved into my satchel and pulled out a package that contained two sardines and five bread rolls (squirrelled away at lunchtime). I asked him to explain to the congregation of adolescent, and forever hungry boys, how it was done. It was one of my earliest engagements with objects, the power of props, and their immutable physical presence. I didn’t exactly act it out, but I was the young boy and here were five loaves and two fishes; it was a challenge, a mischievous appeal to “show us how it’s done, Sir.” The bishop, without revealing any anger, calmly pointed out that he was not the son of God and had no such miraculous powers, that the feeding of the 5,000 was shrouded in mystery and was a splendour to behold—his advice was that I should simply take from the story inspiration to share whatever I had, and to be generous. The crumpled package returned to my satchel as a burden, not easily distributable, only to become waste. That night the housemaster beat me with a cane for being insolent and irreverent.

At the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen in Chelsea, New York City, more than 5,000 homeless and hungry people are fed each week.[7] The Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen offers hope and compassion; its motto is “Soup and Soul”, embodying a philosophy of offering food and a variety of programmes to nourish both the body and the mind. Anyone is welcomed, “without question or qualification.” The Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen maintains a truly open-door policy with an ever-responsive kitchen. Tons of time-limited produce are gifted weekly from the food industries of New York City, requiring the chefs to quickly adapt and invent new menus based upon what arrives at their pantry door.

The world’s great religions deliver miracles every day. The Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen is one of the largest in North America but its prodigious delivery of 1,000 meals every weekday is dwarfed by the 100,000 free meals served daily at the Golden Temple, Amritsar, Punjab, India.[8] Within the extended, and repeatedly reconstructed, compound of this magnificent and serene Sikh temple the clamour and fervour of the world’s largest kitchen unfolds. The tradition of langar, serving free hot meals to people of all faiths, was inaugurated by the first guru of the Sikh people—Guru Nanak—in 1481 and all Sikh gurudwaras continue this tradition but nothing compares to the industrial scale of the langar at the Golden Temple.

Here the food is consistently the same, pure vegetarian and served every day of the year: rotis, rice, a daal of lentils, a vegetarian dish, and kheer (a sweet rice pudding), prepared in enormous vats, hand stirred with paddles, over wood fires, each batch serving approximately 10,000 people. Although there is a permanent kitchen staff (sewadars) of about 300, it is the selflessness and generosity of thousands of volunteers and donors that make this miracle possible.

The scale and magnanimity of the Golden Temple kitchen is rivalled perhaps by the Rosaghara, the traditional kitchen of the Jagannatha Temple of Puri in Odisha.[9] Here 600 chefs, from a sacred sect, work over 250 open hearths. What is most astonishing is that the kitchen has the potential to create 500 varieties of vegetarian food, and 50 different options are prepared every day. The delicious and distinctive food is first offered to the gods of the temple and then distributed to the worshippers, and some sold in the town to support the ongoing and never ceasing enterprise. This is a Hindu temple and like the Sikh gurudwaras, offering sustenance is a spiritual act mandated by the religion’s founders. In Buddhist temples vegetarian and vegan food is offered in return for small donations to raise funds for community work and the upkeep of the temples. The kitchens of world religions, their chefs, devotees, donors, officiates, and volunteers, perform the greatest acts of generosity to counter the hunger of those one billion global citizens placed in peril by economic and political failure, hegemony, and geo-political machination.

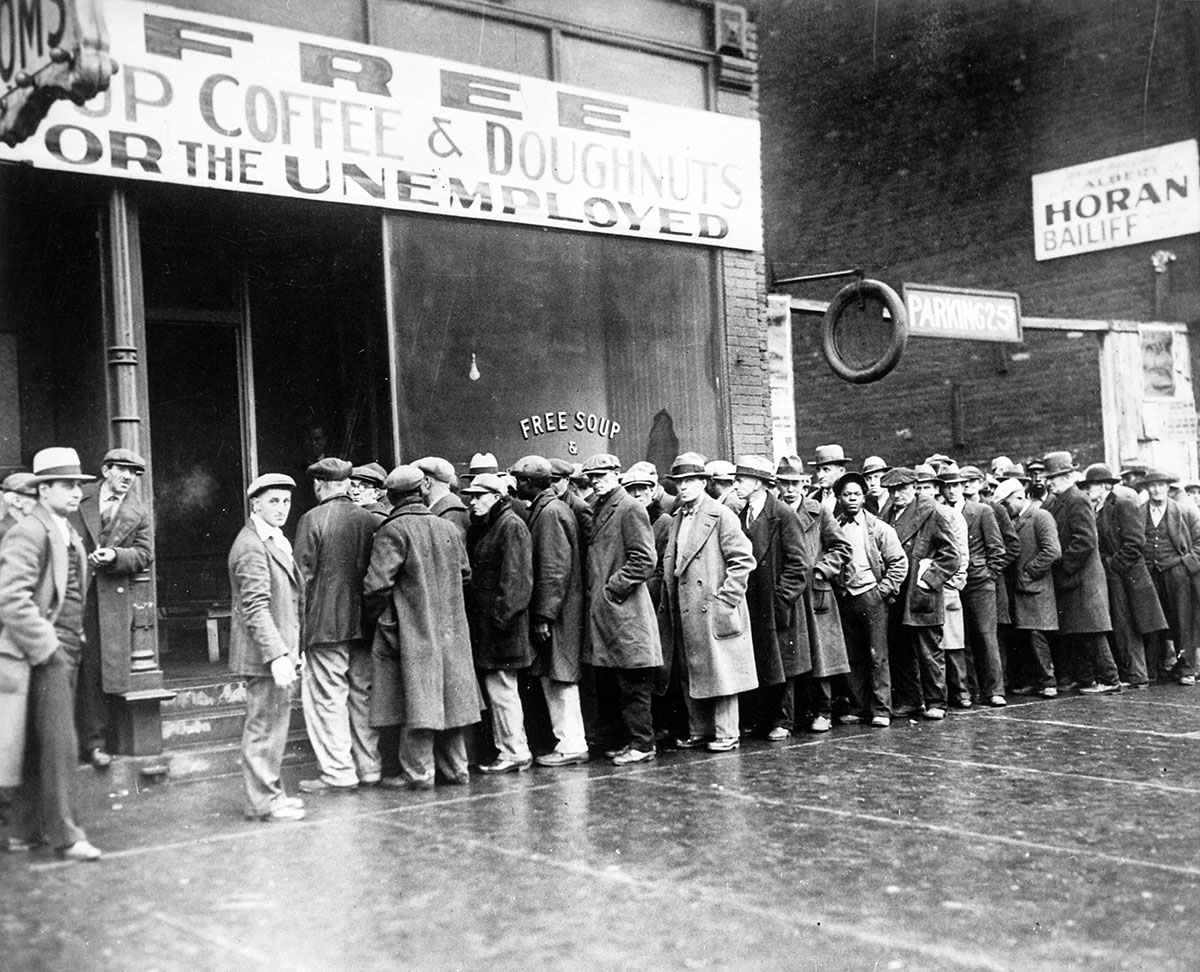

But we should not think supporting the hungry and those in need is only restricted to religious institutions or charities. In Chicago in 1930, Al Capone, America’s most notorious gangster, opened one of the first soup kitchens of the Great Depression. A multitude of dishevelled, jobless, and starving men would gather daily outside 935 South State Street where three free meals, no questions asked, were offered. Reportedly the kitchen managed to offer more than 2,000 meals daily. On Thanksgiving 1930 Capone excelled himself and was able to gain favourable publicity by feeding 5,000 men, women, and children, this biblical integer not lost on Public Enemy Number One. Capone was doing more for the hungry of the Windy City than the state, individual initiatives often cut through the glacial bureaucracy of major institutions.

The soup kitchens of the Great Depression cast a shadow across acts of generosity and radical hospitality. They appear to lack dignity and offer grim comfort for the destitute, the precarity of the hungry only momentarily alleviated and often in bleak and desolate circumstances. A melancholic atmosphere pervades; acts of hospitality are staged in inhospitable settings. The soup kitchens of the 1930s now haunt the food banks and community kitchens of today that are rapidly re-emerging even in the so called “developed countries”, but magnificent efforts are being made to offer food aid with dignity and unbounded charity. As Robert Egger (activist, writer, founder of DC Central Kitchen USA has remarked: “Too often charity is about the redemption of the giver, not the liberation of the receiver.”[10]

If the Chicago gangster Al Capone appears as an unlikely champion of soup kitchens for the destitute and hungry during the Great Depression, the revolutionary, Marxist-Leninist, Black Panther Party (BPP) of the turbulent 1960s California, destabilises all presumptions and prejudices for where profound change (throughout America) in food action might emanate.[11] Like Capone, they were caricatured for their gun-toting, subterranean networking and threat to civic order, but unlike Capone, who often collaborated with police and the authorities, the Black Panther Party origins were as vigilantes, cop-watchers, and defenders of those victimized by racist police. Both were hounded by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). The Black Panther Party legally carried guns under Californian law and courageously policed the police. They also organized the Free Breakfast for School Children Program, one part of their far-reaching and laudable Survival Programs; strategies for “survival pending revolution” that encompassed fifty community and social initiatives that eventually included People’s Free Food Programs.

The Free Breakfast for School Children Program was initiated in January 1969 in Oakland (California) where the Black Panther Party, founded by Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale, was first established in 1966. Within two months a second free breakfast programme opened in San Francisco and by the end of the year the “programme” had become nationwide with free breakfasts being offered to all children in need, from all ethnicities and backgrounds, in nineteen cities where the Black Panther Party had an active presence and political purpose. It is recorded that at its height there were more than thirty-six programmes functioning across America at a time when no such initiative was being adopted at state or federal level. Estimates vary that between 10,000 and 20,000 children daily were offered a variety of “toast, bacon, sausage, eggs, grits, hotcakes, and a glass of juice” before proceeding to school. The programme was coordinated by Ruth Beckford, an Afro-Haitian dancer (“Mother of Black Dance” in the Bay Area) and most of the volunteer staff of the kitchens were women Panthers. Billy X Jennings, the current archivist of the Black Panther Party, who worked at the original “programme” at St Augustine Episcopal Church (West Oakland) in 1969 has said: “This is one of the biggest and baddest things we ever did. And it is still functioning across America […]. That’s what a vanguard party does. We set examples for people to follow.” He is referring here to the fact that the Panther’s Free Breakfast for School Children Program led directly to the US government implementing a national breakfast programme—School Breakfast Program (SBP)—in 1975, modelled on the BPP innovative strategy and framework for delivery. The USA School Breakfast Program now feeds approximately 13 million vulnerable children daily. However, the scheme was not established before the Panther’s programme was subjected to disdain, discredit and defamation perpetrated by national agencies and authorities including the FBI. Why is it that when it comes to addressing food poverty and hunger action the heroic outlaw Robin Hood is often evinced and embodied? Robin Hood, the legend of English folk law, who stole from the rich to give to the poor, does appear to be an archetypal figure for combatting food insecurity and hunger; and the heroic outlaw, the way to cut through glacial and bureaucratic process to confront hunger with urgency and subversive strategies.

The Black Panther Party founders were well-read and conversant with pedagogical research that proved the need for school children to have a nourishing and sustaining breakfast to enable them the best advantage from attending school. Poverty and hunger had to be addressed through action—and lessons in liberation could also be taught during feeding. While the Panthers’ focus remained on empowering and supporting “kids to get the best from schooling” and not be distracted or disaffected due to hunger, the fear that breakfast also nourished radicalization agitated J Edgar Hoover, the director of the FBI—which he founded in 1935 and ran until his death in 1972. Hoover loathed the Black Panther Party with a toxic mixture of hatred and fear—akin to the Sheriff of Nottingham’s persecution of Robin Hood. In May 1969 (only a few months since the establishment of the free food programme) Hoover sent a memo to all FBI officers:

The BCP (Breakfast for Children Program) promotes at least tacit support for the Black Panther Party among naïve individuals and, what is more distressing, it provides the BPP with a ready audience composed of highly impressionable youths. Consequently, the BCP represents the best and most influential activity going for the BPP and as such is potentially the greatest threat to efforts by authorities to neutralize the BPP and destroy what it stands for. (Mascarenhas-Swan)

This declaration caused free breakfasts to be regarded as an act of subversion and thus a legitimate target for “busting fugitives”, permitting random inspection, unremitting disruption, and closure—the Panthers’ breakfasts were criminalized; the children went to school hungry once more.

For several years on Calle Bravo Murillo near the centre of Madrid, Spain, there was a restaurant called Robin Hood. By day, in 2017, it charged its customers a fair price (15–20 Euro) for a hearty breakfast or a two-course lunch and by night it offered free dinners for the homeless and those in need. The income from the daytime paying clientele covered the costs for the evening guests and the aim was not only to offer sustenance but also dignity.

The Robin Hood restaurant opened in 2016 and was the initiative of the charity Mensajeros de la Paz—Messengers of Peace—founded in 1952 by Father Ángel Garcia Rodriguez, who at the age of 80 (in 2017) could often be seen welcoming the homeless and ensuring they enjoyed a generous meal on tables covered with linen, and on fine porcelain plates served by waiters. Father Ángel Garcia Rodriguez, known locally as Padre Ángel, often proclaimed: “I want them to eat with the same dignity as any other customer, and the same quality, with glasses made of crystal, not plastic, and in an atmosphere of friendship and conversation” (Rodriguez). He credits inspiration to Pope Francis “who spoke again and again about the importance of giving people dignity, whether it’s through bread or through work.” Within a year of opening, the Robin Hood restaurant became one of Madrid’s most coveted lunch time reservation destinations, with celebrity chefs offering to do surprise shifts, pop-up appearances, and with other locations being planned. Padre Ángel and the Messengers of Peace continue their charitable work but Robin Hood, as a restaurant, did not survive COVID-19.

However, Robin Hood cannot be suppressed. In India the Robin Hood Army flourishes.[12] It started first on the streets of Delhi in August 2014 and has expanded to reach 406 cities across thirty-six countries. In 2020 it proudly recorded to have served 138 million free meals but also noted that was only 1 per cent of its goal. The Robin Hood Army publishes its balance sheet that reveals a round zero in every column: no revenue, no expenditure, no offices, no employees. It is a digitized initiative, exploring all aspects of social media to expand and realise its mission, viral and boundless, full of youthful optimism and vitality.

We are in the business of spreading smiles. We share our experiences on social media. Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp are our tools to grow. Along the way, our extremely passionate Robins and kind members of the press community have helped drive our mission to the world. The Robin Hood Army is a zero-funds volunteer organization that works to get surplus food from restaurants and communities to serve the less fortunate.

Our “Robins” are largely students and young working professionals—everyone does this in their free time. The lesser fortunate sections of society we serve include homeless families, orphanages, patients from public hospitals and old age homes. (Robin Hood Army)

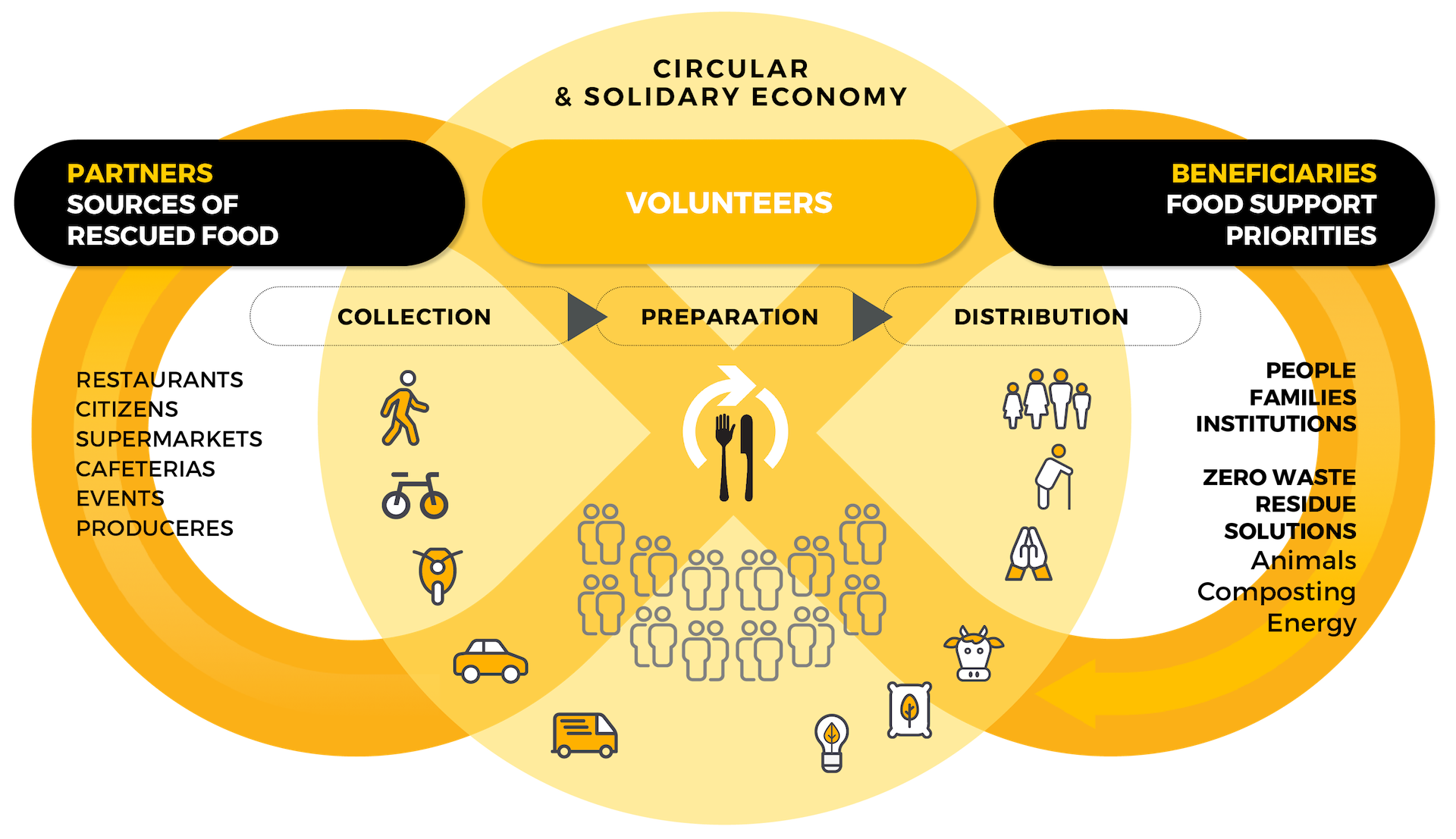

The Robin Hood Army is modelled on the REFOOD network that began in Portugal (now reaching across Spain and Italy), whose core ethos is “stop waste—feed people”.[13] Its ethos stems from offering restaurants (and the food/hospitality industry generally) a choice, an alternative to the disposing of surplus food as waste, rather, allowing its redistribution as sustenance.

The Refood movement rescues tons of good food to stop waste and feed people in need. How? By building a human bridge between excess and necessity. We invite the entire local community to be part of a 100% volunteer movement that transforms not only waste into nutrition, but also the lives of everyone involved in Refood’s goodwill driven, circular and solidary economy. (Refood website)

REFOOD’s roots are as a volunteer organization starting small, specific, and simple—at first a network of restaurants in central Lisbon with two churches offering hospitality and identifying beneficiaries, and then a team of bicyclists collecting surplus food on a daily circuit. Waste transformed into sustenance; the cyclical structure of the organization is the foundation of an alternative economy. And from a single neighbourhood in central Lisbon a complex matrix was spawned throughout southern Europe and then inspiring other initiatives, such as the Robin Hood Army spiralling out from India.

In this last section, following the trajectory of change-making described above, I look to the future for hope, and positive action, in relation to food insecurity, poverty, and hunger. I am most inspired by ground-breaking initiatives made within the restaurant and hospitality industries rather than the arts and the cultural sector. This is perhaps understandable as food is their material and expertise, and they are better able to mobilise kitchens and understand the principles of food waste and propose radical solutions for a different order of food distribution. I want to draw attention to the work of two outstanding chefs, José Andres and Massimo Bottura.

José Andres is an exuberant and passionate Spaniard, larger than life and a force to be reckoned with. He credits his parents for teaching him how to cook and respect nature’s produce, and he spent a formative period at the once world-renowned Catalan restaurant, elBulli, under Ferran Adrià, encountering magical techniques of food transformation. He emigrated to the USA in 1991 and within a few years had established several immensely successful restaurants, winning accolades and Michelin stars. He has an empire of restaurants and emporia, and most recently opened Pig Tail, a Chicago speakeasy cocktail lounge with a sultry nod to Al Capone. But it is his commitment to organize emergency kitchens in the wake of natural disasters and to feed millions of starving people with little concern for his own safety and a total disregard for red tape, obstructionist rules and regulations, and the often-wasteful process of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and many charities that distinguishes him as a force for change.

He formed the World Central Kitchen (WCK) in 2010 and it has created rapid relief kitchens in India, Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Venezuela, Brazil, Mexico, Tonga, the Philippines, and now Ukraine.[14] Its reach is vast and its impact immeasurable. In addition to responding to emergencies often caused by natural catastrophes, it is delivering programmes to train cooks and enable community kitchens, build resilience, and to make long-term change to food insecurities and hunger at appropriate national and domestic levels. In his introductory note to The World Central Kitchen Cookbook, Andres clarifies and pleads:

You see, there’s no right way to feed people in the aftermath of a disaster. It’s a way of listening and learning, of thinking, and of acting in the world that we are sharing in a million and one ways with this book.

Here is your invitation to become one of us, to fill yourself with the spirit of World Central Kitchen. We will together be feeding humanity, feeding hope, one plate at a time. Building longer tables together, you and me, the people of World Central Kitchen. (Andres, The World Central Kitchen Cookbook 8–9)

Andres’ earlier book, We Fed an Island (2018), chronicles the extraordinary work he, and his rapidly assembled team, undertook in Puerto Rico following Hurricane Maria in 2017. It reads like an adventure story bordering on the unbelievable. For his humanitarian work Andres has twice been nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize, and he is often credited for bringing the concept of “small plates” dining to America, the sharing of tapas and multiple appetisers, but the work of WCK is about vast platters of sustenance, prepared in prodigious cauldrons, proffered with dignity—350 million meals to date. No matter how political or humanitarian Andres is in the public sphere, he always grounds his thoughts through food:

Eating isn’t functional. Food relief shouldn’t be either. Whether I am creating an avant garde meal that deconstructs your idea of a familiar meal or a giant pot of rice and chicken that fills your belly, I believe in the transformational power of cooking.

A plate of food is much more than food. It sends a message that someone far away cares about you; that you are not on your own. It’s a beacon of hope that maybe somewhere, something good is happening. (Andres, We Fed an Island 4)

Another highly regarded and multiple Michelin starred chef I would like to draw attention to is Massimo Bottura, the chef patron of Osteria Francescana, in the medieval city, Modena, Italy. Bottura, like José Andres, spent time with Ferran Adrià at elBulli and developed further his skills in new techniques and vision for gastronomic possibilities. He juxtaposes culinary traditions with innovative creation and is especially interested in contemporary art, film, and performance. Since opening Osteria Francescana in 1995, the restaurant has pioneered culinary invention to the application of local produce and languished in the ratings of the top ten restaurants in the world for the last twelve years. But again, as with Andres, it is Bottura’s concern for the poor, homeless, and hungry that gains my admiration here.

Whereas Andres is making urgent and strategic interventions to do with food emergency, rescue, and relief, Bottura is gradually constructing a network of refectories that address food waste, and the profligacy of institutionalised hospitality, by offering high-quality food with great dignity to the homeless and those in need. Bottura connects food directly to culture, and generates welcoming and radical hospitality, in beautiful dining halls. His Refrettorio are the polar opposites of the soup kitchens chronicled earlier, reflecting his interest in contemporary art and design, enshrining generosity, and generating commensality.[15] Essentially, they confront food waste, in a world where there would be enough food for all if there was not such reckless excess, prodigality, and profiteering distribution. Massimo Bottura believes that “the gesture of sitting down to a meal and breaking bread together is the first step toward rebuilding dignity and creating community.”

In terms of methods and creative strategies there are many corresponding factors between the endeavours of Bottura and Andres and theatre practice—between directly satiating hunger (with dignity and generosity) and stimulating the imagination through performance. The belief in the potential for change is fundamental to both, as is the commitment to empower the individual and thus the community. These kitchens appear like studios (or the studios like kitchens), furiously improvising, devising and adapting, urgently co-creating and collaborating, engaging old objects and disused kit for new purposes, transforming empty spaces into safe places—sites of welcome and disbelief—placing trust in the participants, working together with respect, and being guided by empathy.

Both Bottura and Andres have been influenced by Ferran Adrià, the theatrician of the kitchen. Adria has always been aware of the performances enacted in his restaurants, the interplay between servers and diners, dishes and settings, “food as a substance with strong presence” (to use Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett’s term) and the cultural significance of re-staging and re-presentation. Andres and Bottura have taken this work in different directions, but the dynamics of performance remain elevated in their work. I see their work as an urgent provocation to “actual/arts” performance and theatre makers—how can we match or complement their endeavours? How can we create images and actions (speech and song) that illuminate and challenge food poverty, disturb and trouble spectators, and affect change to hunger?

To rephrase something I wrote a few years ago—how could we realise theatre as if it were a strange food from another world that, like one of Ferran Adrià’s creations, provokes bewilderment, rekindling enchantment, inspiring awe and curiosity… lo and behold… as if it were a miraculous food, to be shared not just through an act of collaboration and co-participation but as an act of commensality… of being together to share and partake. Theatre as if it were manna necessary in times of wilderness, alienation, and social upheaval… appearing on the stage like a hoar frost, tasting like bread tempered with oil, like flour with honey, a foam, a suspension of seeds… seeds of change, for perception and the imagination, as if we might digest theatre, as if we might devour theatre.

Food insecurity and climate change, the weather and hunger are inextricably linked but it appears to me that performance is better able to create arresting and disturbing work in relation to climate change, through installations, theatre, public interventions and live art, activism, and protest than it is in relation to hunger, famine, and food poverty. I think this relates to my initial assertion about the difficulty of representation (bounded/limited simulacra) and the challenge to the imagination. Perhaps by linking climate change and food insecurity more overtly, through images and action, the urgent need for global change could be raised. In addition to imagining longer tables José Andres evokes the myth of the self-fulfilling pot of food, regenerating sustenance to support feeding more people one plate at a time.

I can see it clearly in my head, this pot. Think about it: We prepare more than enough food on this planet to feed all the people on it. Every day around the world, our farmers grow enough calories for every single woman, child and man—but still people go hungry. This is not only unjust, it is inhumane. I believe that food is a universal human right, but the forces of our food system, of our agriculture, of our politics, keep this dream from becoming a reality. Can you believe that in the twenty-first century, there are almost a billion people in the world who go to sleep hungry? (Andres, The World Central Kitchen Cookbook)

And so finally, in the more positive and community-spirited telling of the Stone Soup story, we can imagine that, whoever initiates the cooking, once the cauldron is boiling and the stones are immersed, curiosity and a sense of participation lead the villagers to contribute whatever they have. Incrementally they add to the apparent sustenance of stones. One offers a few potatoes, another some carrots. Someone has some beef bones and so the contributions go on (and in) until a wonderful broth bubbles gently. All partake. All are nourished, the Stone Soup is the most wonderous stew they have ever devoured, the stones rest at the bottom of the vessel, their purpose passed. Perhaps these stones could function as the foundation of an artist-driven network, addressing hunger, and act, dare one say perform, in a similar way. For, as José Andres has observed:

Maybe it is not about the pot at all, but more about what goes into the pot. Maybe the question is not about science at all, but about humanity […]. [I]f we each bring something small, a little piece of ourselves, coming together to each help in our own way, we can be working together to fill any pot in the world, wherever there’s a need. (Andres, The World Central Kitchen Cookbook)

[1] Points of Contact: Performance, food and cookery was held in Cardiff 13 to 16 January 1994. In addition to many food-related performances, demonstrations, presentations, and performative banquets, there were papers and panels on hunger strikes, food disorders, fasting, famine, and food poverty.

[2] At the time of preparing this text for print (January 2024) Gaza, under relentless bombardment from Israel and with little aid reaching the starving population, was also heading towards famine.

[3] Luigi Luciani (1842–1919) was an Italian neuroscientist who specialized in in the physiology of respiration, the cardiovascular system, and the cerebral cortex. He made significant scientific contributions to the understanding of the cerebellum and fasting and published A Physiology of Fasting (1899). He conducted experiments on the tissues of Succi during his fasting and distinguished three stages of starvation in human beings: hunger; physiological inanition; and pathological inanition.

[4] The House with the Ocean View was a three-room installation inhabited by Marina Abramović for twelve days in open view of a gallery audience. It was first presented by the Sean Kelly Gallery (New York) from 15 November to 21 December 2002, and described by the gallery as: “[A] public living installation: for the first twelve days of the exhibition Abramovic will fast following a strictly defined regimen in three specially constructed living units in the main gallery space.” See also: https://moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3129.

[5] Force feeding is advocated by governments or authorities as a way of keeping a prisoner or detainee alive so that they serve their full sentence (and avoid public outcry and controversy around the individual who has resorted to such protest). It involves inserting a plastic tube through the nose or mouth down through the throat and oesophagus into the stomach. For a detailed analysis of force feeding see Miller.

[6] Terrence MacSwiney was an author, playwright, and politician. One of his plays was The Revolutionist: A play in five acts (1914). He played an important role in the Irish War of Independence and following the murder of Mayor Tomás Mac Curtain he was elected the Sein Fein Lord Mayor of Cork in April 1920. On 12 August he was arrested on sedition, summarily tried, gaoled, and eventually incarcerated in Brixton Prison. He endured a seventy-four-day hunger strike and died on 30 October 1920. Reflecting on his hunger strike he wrote, “I am confident that my death will do more to smash the British Empire than my release.” His cause and his death garnered world-wide recognition, protest, and admiration.

[7] For full details of the Holy Apostles Soup Kitchen see their website that contains descriptions of their kitchen, fare, mission, and history together with testimonials: https://holyapostlesnyc.org/.

[8] Virtual tours of the Golden Temple Amritsar can be found on their own website: www.goldentempleamritsar.org/ and a YouTube video of the kitchen, food preparation, and serving can be found here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=TT-N5wl0l-s.

[9] The official website of the Jagannatha Temple, Puri can be found here: www.shreejagannatha.in/ and a YouTube video of the kitchen, food preparation and serving can be found here: www.youtube.com/watch?v=PwLMV7i1dQ0.

[10] The thirty-five-year history of DC Central kitchen is fully documented on their own website and the ethos, values, and strategies that underly their commitment to “Fight Hunger Differently” can be found here: https://dccentralkitchen.org/.

[11] The history of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense, including footage of original news reels, documentaries, profiles on prominent members, the founding statements of the Ten Point Platform, and FBI digitized files can be found on the USA National Archives: https://www.archives.gov/research/african-americans/black-power/black-panthers.

[12] The Robin Hood Army website—Hunger is more than a Missing Meal—can be found here: https://robinhoodarmy.com/.

[13] Details on the history, current reach and ambition of REFOOD—Stop Waste/Feed People—can be found here: https://re-food.org/en/home/.

[14] For a full history of the World Central Kitchen and details of all its emergency and sustained projects in response to humanitarian, climate, and community crisis see: https://wck.org/.

[15] Details of Massimo Bottura’s network of Refettorio are captured within his greater project Food for Soul that includes other initiatives such as the Learning Network see: www.foodforsoul.it/.

Andres, José. We Fed an Island. HarperCollins, 2018.

———. The World Central Kitchen Cookbook, edited with Sam Chapple-Sokol. Clarkson Potter, 2023.

Cozzi, Enzo. “Hunger and the future of performance.” Performance Research, vol. 4, no. 1, 1999, pp. 121–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.1999.10871652

Global Performance Studies. “CFP for Issue 5.2: Hunger (concurrent issue with Performance Research),” 16 September 2022. https://gps.psi-web.org/announcement/view/10

Gough, Richard. “Editorial.” Performance Research, vol. 4, no. 1, 1999, pp. iii–iv. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.1999.10871638

Greer, Germaine. Loaves & Wishes: Writers writing on food, edited by. Antonia Till. Virago, 1992.

Kafka, Franz. “Ein Hungerkünstler” (A Hunger Artist). Die neue Rundschau, Vol. XXXIII, Band 2, October 1922, pp. 983–92.

———. A Hunger Artist and Other Stories, translated by Joyce Crick. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Kirshenblatt-Gimblett, Barbara. “Playing to the Senses: Food as a Performance Medium.” Performance Research, vol. 4, no. 1, 1999, pp. 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.1999.10871639

Mascarenhas-Swan, Marc. “Honoring the 44th Anniversary of the Black Panther’s Free Breakfast Programme,” 2013. https://movementgeneration.org/honoring-the-44th-anniversary-of-the-black-panthers-free-breakfast-program/

Miller, Ian. A History of Force Feeding: Hunger strikes, prisons and medical ethics, 1909-1974. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016. Available at www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK385298/

MOMA. “Marina Abramović artist statement, The House with the Ocean View.” 2002 https://moma.org/audio/playlist/243/3129.

Robin Hood Army. “Any questions.” Accessed 29 May 2024. https://robinhoodarmy.com/faqs,

Rodriguez, Father Ángel Garcia. Interview on National Public Radio, 24 January 2017. https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2017/01/24/511267616/spains-robin-hood-restaurant-charges-the-rich-and-feeds-the-poor.

Spartacus Education. “Hunger strikes.” 2021. https://spartacus-educational.com/Whunger.htm