“Environmental Art” is an elective course offered by the Center for General Education at Chung Yuan Christian University (CYCU), Taiwan. With ecological sustainability as its core concept, the course explores the relationship between people and the environment through art. The Tate Gallery describes environmental art as “art that addresses social and political issues relating to the natural and urban environment“ (Tate). Among the subgenres of environmental art—land art, ecological art, and recycled art— the latter two emphasize environmental sustainability and the harmonious coexistence between people and nature, and ecological art is the most relevant to hunger. As “ecology” is “the study of the relationships between living organisms, including humans, and their physical environment” (ESA), one of the ecological art’s main concerns is the relationships between people, produce, and food.

Although the course moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic, I and students were able to complete The Hunger Project virtually as the final assignment for the course. The following sections highlight the pedagogical components and the results of the students’ collaborative exploration of “hunger” in Taiwan and in the global context. The final portion of the article considers the ramifications of the pedagogical process, such as providing an online teaching approach, presenting a different setting for performance, and producing an additional pathway to hunger action.

In 1962, marine biologist and nature writer, Rachel Carson published Silent Spring to warn the world against the human species’ assault on the environment—our “contamination of the air, earth, rivers, and sea with dangerous and even lethal chemicals” (Carson 6). This seminal book underlined Carson’s vision of the oneness of all life, and her courage in sounding the alarm, according to Carson’s biographer Linda Lear, “shaped the contemporary environment movement and anticipated the global crisis we face in the 21st Century” (Lear xxii).

Among those influenced by Carson’s cautionary tale was an artist-couple Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison. It was Helen who read Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, which became “a critical influence in their decision in the early 1970s to only create works that would benefit the ecosystem (Douglas and Fremantle). With this newfound direction and determined response, the Harrisons proceeded to collaborate on numerous interdisciplinary and complex projects. Their earliest documented ecologically-centered works, Making Earth and Survival Pieces, became examples that I present with marvel and fondness in my Environmental Art and Ecological Art courses. In Making Earth (1970), the Harrisons blended and watered a mixture of sand, clay, sewage sludge, leaf material, and chicken, cow, and horse manure repeatedly for a four-month period until it emitted a rich, forest-floor smell and could be tasted. The four Survival Pieces involved creating living ecosystems within a relatively small scale, such that they could be contained within a museum exhibition. For example, Hog Pasture (1970–71) comprised a 8 foot x 12 foot x 18 inch wooden container of earth and grass, as well as a light box of equal size above. The Harrisons proposed to have a pig living in this frame during the museum exhibition, but the museum refused. In a 2012 reconstruction, the Harrisons were finally able to include a 120-pound pig named Wilma interacting with a pasture at the Geffen Museum in Los Angeles. Shrimp Farm and Portable Fish Farm were both completed in 1971, and according to the Harrisons, Shrimp Farm was one of the simplest discrete ecosystems extant. It included four “ponds” filled with water of varying degrees of salinity, from seawater to brine that was ten times saltier than seawater. Salt-responsive algae in each pond resulted in a “three-dimensional color field painting of blue-green, dark yellowish-green, brick red and white.” Algae-eating shrimp were then added to the ponds, so that the colors continually changed. With an awareness of “the loss of orchards and farms to suburban and industrial development and resulting smog” in Orange County, California, Portable Orchard (1972–73) also utilized installation with harvesting and feasting to experiment with tree types that would survive in an indoor environment.

The naissance and burgeoning of ecological art prompted significant theorization. For example, ecological art’s ethos—a turn away from consumeristic culture toward an ecocentric worldview is explored by Suzi Gablik in The Reenchantment of Art. Through her cultural critique, Galik analyzes the central cause of humans’ destruction of earth and looks toward art as an instrument for restoration, foremost a restoration of our belief framework. She states that contemporary culture has “failed to generate a living cosmology that would enable” people to cherish the sacredness and interconnectedness of life (Gablik 82). Gablik suggests that art, “moved by empathic attunement,” can facilitate the return of a reverence for life and a holistic awareness of all living beings’ interrelatedness (Gablik 88). This attunement, for Gablik, signifies a paradigm shift away from the consumeristic framework that encourages a mindless craze of production, consumption, waste and greed; and toward one of holistic reengagement with our intellect, emotions, psyche, ethics, and spirituality (Gablik 2). This engagement with the whole being is evident in the Hunger Project works introduced below, which feature my students’ exploration of the various dimensions of the self and the world in relation to hunger.

Along with the repositioning of our worldview, Gablik proposes a revision of art’s stance from the modernist myths of “neutrality and autonomy” to one that is “social and purposeful” (Gablik 4). The new relationship between art and society that Gablik envisions would replace the current “anti-ecological, unhealthy and destructive” psychic and social structures with new patterns of “mutualism and the development of an active and practical dialogue with the environment” (Gablik 5–6). In this new framework, art would adopt an ecological perspective, transform its goals, and take on an integrative role in the complex set of relationships in which art is situated (Gablik 7–8). This paradigm shift is echoed by Linda Weintraub in To Life! Eco Art in Pursuit of A Sustainable Planet (2012), which further explores ecological art’s characteristics. Weintraub argues that ecological art is innovative because the scales, mediums, processes, and themes it introduces correlate with worsening environmental woes and determined efforts to remediate them (Weintraub 5). Whereas ecological art may be criticized as being overly instrumentalized, focusing on outcomes rather than aesthetic forms, Weintraub justifies the functionality of ecological art by pointing out that art has often served various functions in different cultures, and that artists traditionally serve the needs of their contemporaries. In the present moment, as the foundations that sustain us are threatened, we have a need for artistic innovations that develop utilitarian strategies to counter problems such as pollution, resource depletion, climate change, and escalating populations (Weintraub 5–6). My students’ works answer this social and ecological turn as they investigate the multifaceted problems associated with hunger, such as climate change, unequal access to resources, dominance and conflict, othering, and the infringement of human rights.

Acknowledging the common goal between artists and ecologists in today’s environmental movement, Weintraub outlines four attributes that characterize ecological art: topics, interconnection, dynamism, and ecocentrism:

topic identifies the dominant idea and determines the work’s material and expressive components; interconnections apply to the relationships between the physical constructs of a work of art and between the work of art and the context in which it exists; dynamism emphasizes actions over objects, and changes over ingredients; ecocentrism guides thematic interpretations as well as decisions regarding the resources consumed and the wastes generated at each juncture of the art process. (Weintraub 6)

Foregrounding ecocentrism as the hallmark of ecological art, Weintraub differentiates this art from the genres of the 1960s and 1970s, including vanguard art. She suggests that ecological art is premised on “the principle that humans are not more important than other entities on Earth,” as it sees the world from the vantage point of a sustainable planet (7). This ethos deviates from the anthropocentric cultural norm in other art that privileges human welfare and experiences (9).

Mark A. Cheetham also contributes to the interpretation of ecological art through Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the ‘60s. He describes ecological art as “a range of contemporary practices that investigate the interconnected environmental, aesthetic, social, and political relationships between human and non-human animals as well as inanimate material through the visual arts” (1). Cheetham remarks on the trans-disciplinary nature of ecological art, stating that eco art stands out from other forms of contemporary art by transcending conventional borders of inquiry (3). To aid in the understanding of contemporary ecological art, Cheetham offers three interconnected tendencies: direct action, aesthetic separation and withdrawal, and articulation. Among them, direct action and aesthetic separation are the most relevant to the methodology and nature of The Hunger Project. Regarding direct action, Cheetham draws a connection between land-reclamation projects from the late 1970s through late 1990s, citing artists such as Robert Morris, Mel Chin, Jackie Brookner, and Viet Ngo, and the “site-reformative” ecological art projects of today (9, borrowing the term from Flint Collins). He elaborates on how these interventions, past and present, all seek to engage the public and the government intellectually as well as emotionally—to be “informative in ways that can change people's behavior toward the environment” (10). Cheetham also refers to artist Jackie Brookner's and philosopher Lorraine Code's ideas on the goal and function of ecological art and art as a field: the restoration of human values. Brookner recognizes that restoring ecosystems is insufficient if we do not reexamine our values and identifications. She sees a need to make restorative processes more accessible in order to draw the attention, imagination, and heart of the public, and believes that art is a medium that achieves this (Cheetham 9–10, Brookner 100). This observation relates to Cheetham's notion of aesthetic separation, distinguishing the aesthetic and artistic aspects of ecological art practices from political activism and from scientific and engineering fields. He posits art's ability to make a difference lies within its difference and that art must be identifiable as such if it is to have an effect (Cheetham 11).

In the field of theater and performance, similar shifts toward ecological-minded art making are emphasized by Una Chaudhuri, Theresa J. May, Arden Thomas, and Linda Woynarski, among others. Chaudhuri identifies the theater as “the site of both ecological alienation and potential ecological consciousness,” and asserts that in order for theater to become the site of ecological consciousness, it must make space for the acknowledgement of “the rupture between humans and nature” (25, 28). However, Woyanrski suggests that “ideas of diversity, variety, circularity and multivocality are more effective in engaging the public on climate change” (15, 19). She advocates the idea of “ecodramaturgy”, a term she attributes to Theresa J. May, who defines it as “theater and performance making that puts ecological reciprocity and community at the center of its theatrical and thematic intent” (Woynarski 9; Arons and May 4). Thomas elaborates on the potential of ecodramaturgy and maintains that ecodramaturgical practices could shift the paradigms of human-nature relations by animating “the collective imagination towards a deeper sense of our material embeddedness in and accountability for the ecomaterial world” (201). For Woynarski, what is required is an alternate perspective that decenters the human, questions neoliberal environmental logic and reimagines the nature/culture binary. In her view, ecodramaturgical theater and performance practices can help us make ecological meaning and become attendant to the different experiences, complexities, and injustices it entails (Woynarski 10). For Woynarski, it is crucial to consider performance works from an ecological intersectional point of view and examine ways of viewing and making, as well as narratives, values, politics and ethics (11).

The theoretical explorations above contain several common concerns, such as a restoration of values, intersectional and holistic approaches, as well as a paradigm shift toward ecoconsciousness, one that perceives the world from a planetary perspective and acknowledges the interconnectedness of all earthly elements. These themes are also the course objectives of my Environmental Art course, which I explore in the next section.

As a teacher of general education in Taiwan, I confront many challenges in trying to promote ecological awareness and behavior not only as “head” knowledge, but also in relation to enacted experience. First, the relationship between university students and their general education teachers differs from that between students and their professors in their major fields of study. The length of time and the depth of the level of interaction between the latter encourage a mentor-mentee relationship. A general education instructor and her students, on the other hand, meet for 18 weeks compared to the four to five years they have with their major-study professors. Despite the limited interaction time frame and the difficulty in assessing students' change toward ecoconscious behavior, there are advantages to facilitating a general education course. For instance, having a class of students from different fields of study means the interdisciplinary and collaborative nature that characterizes many ecological art projects can be emulated. Students can share and exchange different perspectives and approaches during their research process, and combine their skill sets to create stronger works, some of which are delineated below.

Through lectures, the Environmental Art course first introduced ecological art and performance art examples that point to the relationship between society and environmental problems. The sustainability-minded ecological artworks presented to students include the Hungarian-American artist Agnes Denes’ Wheatfield: A Confrontation, Robin Greenfield's Trash Me, and Mathilde Roussel’s Living Sculptures. The following section summarizes these projects and considers their pedagogical implications for reconceptualizing knowledge.

In the four months over spring and summer of 1982, Agnes Denes realized her work, Wheatfield: A Confrontation. In the course of this project, her team cleared the “rubble-strewn” Battery Park Landfill in Downtown Manhattan and planted two acres of golden wheat. This action and the “over 1000 pounds of healthy” harvested crop in midsummer aimed to draw attention to “mismanagement, waste, world hunger and ecological concerns.” According to Denes, this work pointed to “our misplaced priorities.” Then from 1987–90, in an exhibition organized by the Minnesota Museum of Art, “The International Art Show for the End of World Hunger,” the harvested grain “traveled to twenty-eight cities around the world, during which the seeds were carried away by people who planted them in many parts of the globe” (Denes).

In 2012, Mathilde Roussel created a series of Living Sculptures with recycled metal and fabric structures filled with soil and wheat seeds. These human-shaped constructions transform over time, from gray metal frames filled with brown earth, to forms overtaken with new green grass, and eventually to dried and drooping plant fibers. This visible process of growth and decay allows the viewer to contemplate the relationship between edible elements in the natural world and the human body. Through these so-called living grass sculptures, Roussel not only pointed to “the power of food and its effects on human organs, but also to food cycles in the world — of abundance, of famine” (Roussel).

More recently, from 2014 to the present, the American environmental activist, Robin Greenfield, addressed food waste and demonstrated food freedom by dumpster-diving and foraging. For example, Greenfield completed two bike rides across the United States living on food from grocery store dumpsters. His website shared statistics on food waste and food insecurity in the USA, as well as photographs that visualize the large quantity of “good food” he acquired from numerous “dumpster scores.” Through these actions, Greenfield promoted the “donate not dump” concept of various food rescue programs (Greenfield).

Along with other ecological art pieces like Helen and Newton Harrison’s Survival Pieces, David Nash’s Ash Dome, Amanda Schachter and Alexander Levi’s Harvest Dome 2.0, Hans Haacke's Rhine Water Purification Plant, as well as Agnes Denes’ Tree Mountain, these examples add to conventional understanding of knowledge, as they demonstrate interventionist strategies and hands-on processes as ways of working and forming knowledge. If ecological art is ecocentric and divergent in approaches, an ecologically-responsive pedagogy in the present climate might also adopt the same ecotropic ethos and multiple perspectives. My philosophy is that students would only care for someone or something that they know well. Therefore, in order to encourage an ecocentric mindset in students, it is important to first help them connect with nature.

Using the above examples as a springboard, my students considered topics such as the access and distribution of food, as well as the question: why does the lack and the excess of food coexist? From May 25 to the end of June, 2022, university courses moved online due to the COVID-19 pandemic in Taiwan. Therefore, the entire Hunger Project was facilitated online over a period of 3.5 weeks. During this time, students kept busy with online research, data presentation, group brainstorming and discussions, making art, and web page editing. The project culminated in end-of-term online presentations of each group's website content. In these presentations, students from two course sessions highlighted their findings and reflections on hunger and articulated their art concepts. The paragraphs below explicate the pedagogical steps that led to the final presentations.

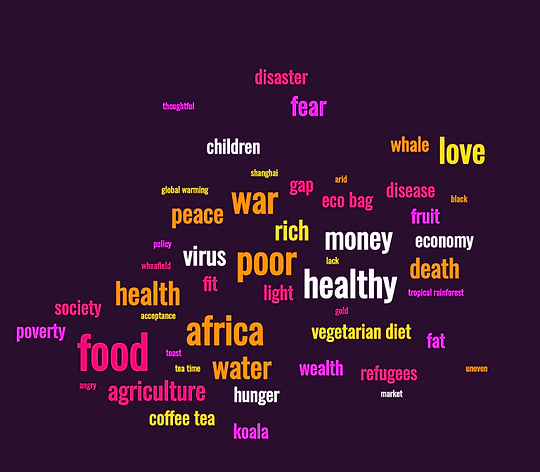

With the UN Sustainable Development Goal 2 (UNDP), “Zero Hunger”, as a starting point, I facilitated The Hunger Project in an online classroom. Microsoft Teams served as the main classroom, and the LINE messaging app was used as an additional communication platform. The brainstorming session started with a group word association game: “which words come up when we hear the word ‘hunger’?” The students listed their word associations on a Google Document. Then, I utilized an online word cloud generator to visualize all of the students’ hunger-related ideas.

The word clouds enabled students to consider the most mentioned words as potential key ideas to their project. However, it is also important to note that less-mentioned words are also significant and worth one's attention.

After the word association and hunger statistics research in the online classroom, each group was asked to create an artwork that comments on hunger. The groups could choose from any dimensions of hunger: physical, emotional, mental, or spiritual. For an effective art piece, I reminded the students to first consider their works’ concept, message, and purpose, followed by method and materials. In tandem with the course's environmental sustainability theme, the students were encouraged to prioritize recycled materials for their artwork. The task also asked that the form of the final product should illustrate the creative concept with clarity.

In the following three weeks, each group discussed its work concepts with I, who provided pointers for fine-tuning their ideas. Occasionally, questions on art designs were raised and responded to. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, although some students met in smaller groups to complete their artworks and webpage, most collaborated online. The most common collaborative approach was one in which individuals completed their respective assigned part of the project, on their own time, and presented the result as a whole. However, one group's process stood out, as they created their artwork together via video conferencing. Group members worked on their respective parts of the art project simultaneously, with the advantage of giving and receiving real-time suggestions and feedback from one another in the process.

Concurrently, I and the students created content for The Hunger Project Website (https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject). I outlined The Hunger Project’s concept and pedagogy, and sixteen groups of students from two course sessions presented their research findings, work concepts, art creations, and reflections. A few groups went further, calling for action and offering solutions to the hunger issues explicated on their webpages. The featured artworks were diverse in form, including drawings, digital collages, as well as sculptures and installations made from natural, synthetic, and found materials. The chosen topics ranged from education, social class, healthcare, agriculture, direct causes of famine, as well as current events, such as the pandemic, the Ukraine-Russo war, and human rights in the Shanghai quarantine. The geographical focus also encompassed local, regional, and global scales: they looked within themselves, around Taiwan, across the strait to China's Shanghai and further inland to Xinjiang, and across continents to Europe and Africa. These varied interpretations of hunger are highlighted in the next section.

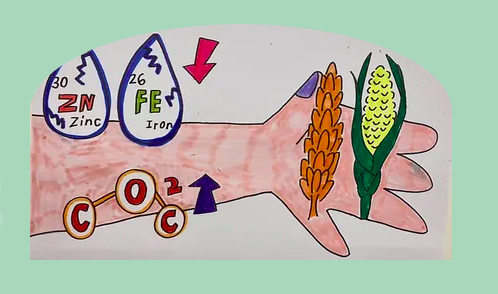

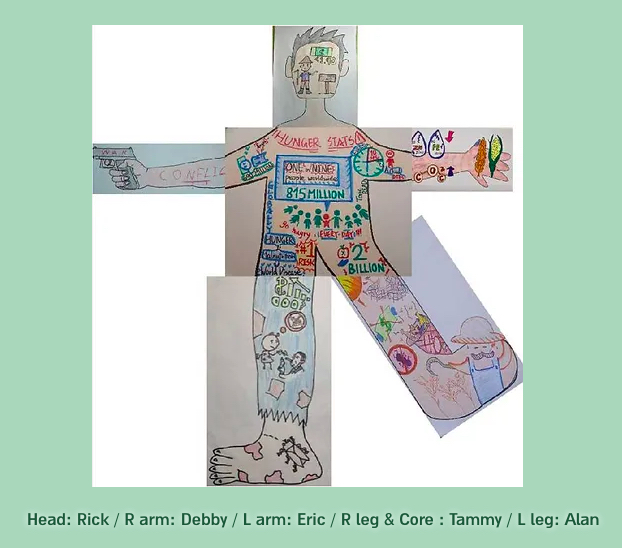

The group calling themselves TOXICREADS took the most literal approach to collaboration. Their Mr. Hunger is a literal collage of the various causes of hunger (see figures 2–5). The message “You're hungry, they're starving, there's a difference” distinguishes hunger as a mild discomfort from extreme hunger suffered by those in severe poverty, famine, and war. Then with additional texts and drawings, each member proceeded to illustrate hunger statistics, war, climate change, poverty, and an unstable market on Mr. Hunger’s head, torso, and limbs. Mapping the myriad and interconnected reasons for starvation and layering them on a “person,” albeit imagined, TOXICREADS brought these dire problems visually to the physical body, and thus closer to home.

Another group, My Goodness, linked social class with food access and consumption in Taiwan. They displayed the “Taiwan Hunger Map 2020” to inform the viewer that not only Taiwan's southernmost county has the highest density of hunger, but also 1 out of 100 people in Taiwan suffer from starvation. Their artworks comprise four digital collage-portraits of the “characters” and “food types” of the homeless, the low-income, the middle-class, and the rich class. Visually, all four images place the corresponding “food type” in the foreground, the figure(s) in the midground, and the shelter in the background. This similarity in composition creates a sense of unity in the series (figures 6–9). While the style and content of each digital image matched its concept, the ones portraying the homeless and the low-income are the most visually effective. In the “homeless” collage, a weathered hand picks up food scraps while homeless people linger in a lobby. The “lower-income” collage features an older person pushing a tricycle, loaded with either her meager possessions or recycled materials that could be exchanged for a minimal sum. She treads on piles of “ugly food” that also seem discarded. Texts inform the reader: “1 year of food waste in Taiwan equals 20 years of food for low income level” (My Goodness). In both images, the viewers are confronted with the almost overwhelming closeups of food waste and a haunting desperation created by the contrast between the monotone backgrounds and colorful foregrounds.

Conceptually, the narratives for the middle class and the rich are less based on scientific data, and more on imagination, or created from observation and association. Noteworthy is the portrayal of the rich: in a spacious, designer-decorated interior, a man throws a bundle of cash in the air and dances with enthusiasm and abandon on mountains of cash and a spread of intricate banquet dishes typical in Taiwan. This narrative and the almost overly saturated colors combine to achieve a sense of theatrical absurdity. The abundant food and cash seem to fill and spill over the visual space, recalling horror vacui. The formal choice of filling the entire space reveals the students' perception of wealthy desires: obsessive acquisition of money and resources, excessive consumption, and unnecessary waste. The saturation of the picture plane underpins the perceived over-the-top, frivolous lifestyle of the wealthy, exemplified by the lavish banquet and the dancing figure. The surplus hoard of cash was so great that the man could afford to throw money around without care. This representation, juxtaposed with collaged images representing the experiences of the homeless and low-income, becomes ironic and farcical: the hunger of the homeless and the low income is physical, whereas the hunger of the wealthy is insatiable greed.

While My Goodness interpreted hunger in relation to social class, the group, Manberdyni shed light on “the connection between hunger and the unhoused” through their work Shelter. Their “digital mosaic art project,” a castle built from images of the unhoused, conveyed the following idea: “When we think of castles, we think of warm, safe, protected, and sheltered. We believe that unhoused people want a shelter; a roof over their head, a comfortable and warm place to stay, and this idea of shelter to them is as dreamy as this castle” (Manberdyni). The grayscale webpage and the same monotone collaged castle underscored the unhoused's bleak, tenuous, and impenetrable “dream” for such a basic need. Listing “hunger facts” and “the unhoused facts” side by side, Manberdyni also touched on the COVID-19 pandemic, which not only exacerbates the plight of those experiencing food insecurity prior to the outbreak, but also puts them at “greater risks of negative physical and mental health consequences.” The pandemic, according to the students, “intensified the issue of food availability, food safety, food distribution, and the significance of detecting flaws in our local food systems.” To help reduce hunger among the unhoused, Manderbyni suggested volunteering, donations, raising awareness, employment, and advocacy.

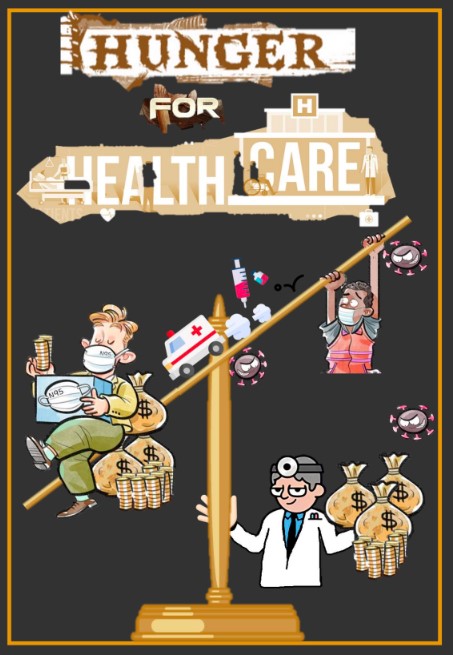

TPELOVECGK also examined the COVID-19 pandemic in relation to the hunger for being healthy, as well as healthcare disparities. Their poster, an assemblage of found digital illustrations, depicts an oversized scale held by a doctor and “a rich man and a poor guy” on either side (figure 10). The rich man, surrounded by bags of cash and piles of golden coins, sits comfortably on and weighs down his end of the scale. Whereas the “poor guy”, attacked by the coronavirus, tries in vain to tip the scale back in balance and watches the ambulance and vaccine race toward the rich man. The group writes, “A rich man gets more vaccines and resources by his wealth and power, on the other hand, poor guys have nothing.” Drawing from numerous news reports, including data from the World Bank and WHO, TPELOVECGK pointed out the plight of those suffering poverty and a lack of access to essential healthcare. Their research not only indicated a health gap between the rich and poor, but also a widening economic gap due to the COVID-19 pandemic, in which healthcare expenses pushed more to extreme poverty (TPELOVECGK). Thus, a cycle of deficit in health and wealth perpetuates.

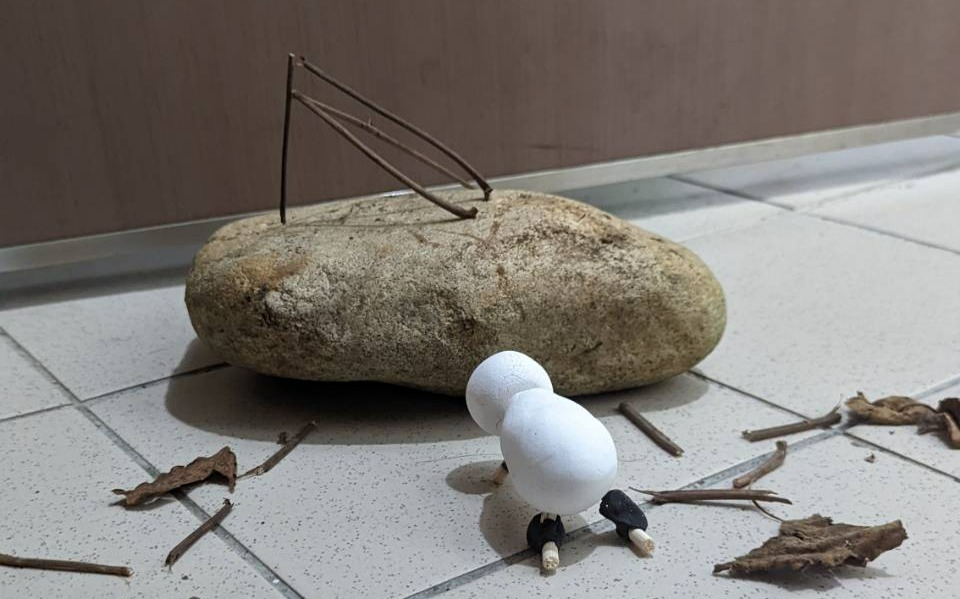

In addition to physical hunger, the group Babysitter also showcased the emotional hunger for love, the spiritual hunger for a supreme being, and the hunger for knowledge in the mind. They created miniature scenes with manmade and natural materials found on their desks and in the garden of their dormitory (figures 11–14). Each of the four mini sculpture installations, situated at the corners of a cardboard box, displays a white paper clay figure suffering from a type of hunger. In the emotional hunger scene, an unbecoming figure with a red “X” across his face holds a heart in one hand and a rose on the other (figure 11). This vignette visualizes the inability of “an ugly person”, as the group puts it, to find love and acceptance due to the world's superficialness. In the spiritual hunger scene, the figure bows to an abstract construction on a big rock. This set comments on the “blind fabrication” of a transcendent existence “when life becomes difficult and desires cannot be satisfied,” which could either “help people get through difficult times” or “backfire” (figure 12). Of the four vignettes, the greatest visual contrast can be found between “mental hunger” and “physical hunger”. While the mental hunger scene is almost saturated with various types of lines, colors, forms, and materials, the physical hunger scene's surroundings are stark and barren. This barrenness corresponds with the hunched, hollowed-eyed, famished figure on a piece of dried, brown leaf atop an elongated rock (figure 13). Three thin bamboo sticks are pressed into this figure's chest to express thinness to the bones. And in the desperation of hunger, this figure picks up unappetizing, black bits of food.

In contrast to the minimalist work above, the mental hunger installation is filled with objects. Speaking to the “inherent inequality in our education system” that leaves many people hungry in the mind, the story presents a girl surrounded by obstacles that prevent her from obtaining knowledge. In this story, her bondage by her gender and the law of her country denies her access to education. “The land beneath her is a field of barren rocks, where the tree of knowledge can never grow. Around her are books full of blank pages and a TV showing only static. She reaches her hand up, hoping to reach the book, but red threads tie her down” (figure 14) (Babysitter). Babysitter provided some antidotes: SDGs 4: Quality Education and advocacy for freedom of speech/information to enrich the mind; faith, hope, and purpose in life for spiritual fulfillment; and friendship, love, and affection for emotional sustenance. Like many other groups of students, Babysitter recognized the complex contributing factors to poverty, a root cause of physical hunger, and encouraged awareness to vulnerable regions, advocacy, and participation in non-profit and charity work.

Furthermore, some students addressed the hunger for human rights. They approached this question from an intersectional approach to hunger dynamics and food inequality, linking these problems to certain populations that suffer compounded challenges and marginalization. Focusing on hunger caused by recent international conflicts, the group, XXTOBEJFXX discussed the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on the various regions of the globe. They composed a digital poster to represent the most impacted countries, deserted land, a sparsity of food, and people’s yearning for food (XXTOBEJFXX). The group Fun Jin Chee drew attention to the PRC’s inhumane COVID-19 pandemic prevention policies, particularly the Shanghai lockdown and the resultant famine. Their text and artworks convey a sharp criticism. Their works, albeit rudimentary in execution and craftsmanship, highlight the absurdity of the situation. One student drew “The Siege of Shanghai,” in which one single “dummy” dressed in a “I love China” t-shirt pulls and ingests grass from the ground. The student found irony in his observation: “Under the pressure of the political party, the mainland people still believe in their party and believe that the government will save them. At the last moment of despair, people who could not suppress their hunger began to pull grass from the ground, in sharp contrast to the determination to believe in the party” (Fun Jin Chee).

Another group, Get All Pass, also looked across the Taiwan Strait towards China and underlined the human rights crisis in Xinjiang. The persecution of the Uyghurs and the Xinjiang cotton controversy garnered attention not only in Australia, New Zealand, the UK, US, and the EU, but also in Taiwan. As the waves of the Xinjiang cotton controversy intensified, President Tsai, in a Facebook post on March 26, 2021, called for Beijing to carefully reconsider their pressuring of certain companies. She maintained that allowing sentiments of nationalism and patriotism to go unchecked would not bring any positive outcome, nor will it lead to China becoming a so-called “major responsible country.” Tsai commented that the focal point of the incident was human rights, a universal value, and urged Beijing authorities to heed human rights issues of the Uyghurs: “Only by stopping the oppressions can international questioning and antagonistic conflicts be resolved” (Central News Agency).

President Tsai’s call was reiterated and enacted three days later by nine Democratic Progressive Party and New Power Party legislators, who stood in front of the Legislative Yuan, wearing tops by the brands counter-boycotted by the Chinese government and people. They held up placards that read: “Protect Human Rights, X Blood & Sweat Cotton”; “Anti Oppression, Guard Human Rights”; “Voicing Support for Uyghurs”; and “Support Companies with a Conscience.” This action followed a string of events, encapsulated by H&M and several other brands’ announcement of their dissociation from Xinjiang cotton and the consequent wave of condemnation and boycotting of these brands, including over 50 entertainment figures from China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan breaking their endorsement contracts with related brands. A few Taiwanese show business performers joined a Chinese counter-boycott, but they were criticized by many members of Taiwan’s general public via social media and news outlets (FTV). A public opinion poll showed that 65.63% of the respondents would stop supporting Taiwanese entertainers who endorsed Xinjiang cotton (NOWnews). The then Chief of Ministry of Culture, Lee Yung-te (李永得) also commented: “It is understandable that they may have some unspeakable challenges. However, human rights are a universal value. This is about a choice of values, not a matter of commercial profit“ (FTV).

Although voices and reactions on PRC’s treatment of the Uyghurs and other Muslim minority groups may vary due to Taiwan citizens’ divergent political and economic interests, the students of Get All Pass condemned PRC’s denial as untruthful. One group member titled his work statement “Falsity” and drew a mirror image of a man, one half alive and one half dead with a bodily shell. Addressing his group’s aim to promote “the desire for human rights and freedom,” he wrote: “Under the false claim of China, Xinjiang people seem to be happy and no different from other people. They have lost the most basic freedom they should have. Under that false appearance, they actually have nothing,” only the empty shells of bodies labeled “human beings…” (Get All Pass).

Another member of the group Fun Jin Chee, a Kazakh exchange student, combined a McDonalds Happy Meal with found objects to show the involuntary fasting due to food shortage in Shanghai (figure 15). Connecting the ideas of fast food and fasting, he jabbed a thermometer into the hamburger. The unnatural juxtaposition of the inedible instrument and the hamburger is jarring. This may refer to the intrusive, inconvenient yet preemptive government policy of measuring people’s body temperature upon entry to shops, school, and other public buildings, which became part of Taiwan’s daily life to prevent an island-wide COVID-19 outbreak after April 1, 2020. Beside the hamburger on the soft drink cup, a pencil-drawn frowning face with a drop of tear at the corner of an eye wears a real mask, another object ubiquitous during the pandemic. The iconography of fast food items and their personification bring to mind fast food and delivery workers in Taiwan. The pandemic worsened the working conditions of these precarious couriers, along with mask production line workers and taxi drivers. As the general population went into quarantine in the safe confines of their homes, the need for food and goods delivery increased all of a sudden, resulting in delivery workers going into overdrive. At the same time, in order to meet the expectant hiking demands of masks and maintain their affordability, Taiwan’s Ministry of Economic Affairs implemented emergency measures and requested domestic mask manufacturers to increase mask production to nearly ten times the pre-pandemic output within three months. As a result, mask production line and delivery workers relayed night and day during the Lunar New Year Holidays, taking 12-hours shifts for seven consecutive days at a time. Even teams of military reservists formed production lines to help (Leua, 38, 40–41; Huang and Chen).

As exemplified above, The Hunger Project showcased diverse dimensions of hunger through various artistic forms. Viewing the website, it is apparent that some works were more successful in translating their messages into visual expressions than the others. At times, there is a gap between the work concept and the artistic outcome. Because most students in the Environmental Art course are not art and design majors, the visual aspect of their work can appear basic. However, the significance of The Hunger Project lies not in the content or artistic quality of the students’ works, but in their learning process. The following section reflects on the pedagogical process, its limitations and potentials, and its relationship to hunger action and performance.

Compared to teaching in an actual classroom, the online format seems to result in a decreased number of instructor-student exchanges. In my experience, my physical presence enables a more immediate and free-flowing dynamic between instructor and students. Perhaps this immediacy is due to the course participants’ ability to see each other. For instance, my availability, the students’ level of engagement, as well as their body language, expressions, and progress are more easily discernible in a face to face context. In a physical classroom on campus and during a 150-minute Environmental Art course session, I would on average make three to four rounds among student groups. This creates plenty of opportunities for questions and feedback. When I am observing the class from the podium, any student can raise their hand to obtain assistance. This kind of set-up tends to elicit more conversations between students and I, with more follow up questions and more elaboration of ideas.

The online classroom seems to result in a different type of interaction, perhaps due to technical practicalities or limitations. During the COVID-19 involuntary move from the physical to the online classroom that coincided with The Hunger Project, I observed a change in student-instructor dynamics. Although a rapport was formed by the face to face sessions that already took place, the move to online learning magnified the remoteness and the associated decreased contact in “remote learning.“ In the synchronous online classroom using Microsoft Teams, although each student could observe my video image, I was unable to see most of my students’ faces and gauge their reactions immediately on the computer screen. My strategy to solicit feedback was to ask students questions both verbally and via text in the chat space, and read their written responses. Also, during small group discussions, Microsoft Teams did not facilitate the function for I to visit each breakout room. As a result, when a small group had a question for me, they either had to return to the main meeting room or use the LINE app. In an 150-minute online Environmental Art class session, I only spoke with each group twice at most. Although the students can contact me via the class LINE group chat during and outside of class time, very few did so.

However, the decreased interaction between the students and me during the creation of The Hunger Project is not necessarily a negative. It could mean that I communicated the project’s objectives clearly in the beginning, and thus fewer students sought clarifications. It might also indicate an increased independence of the students from my input and more lateral collaboration among student group members. Yet the sudden move to online teaching and learning toward the last third of the Spring semester certainly challenged both I and students to adapt quickly and adjust strategies.

The benefits and complexities of online teaching/distance learning in performance pedagogy have been explored by Mark Pedelty and Joy Hamilton, as well as by Felipe Cervera, Theron Schmidt, and Hannah Schwadron. Using their Environmental Communication course as example, Pedelty and Hamilton reflect on the course design and outcome. They coupled distance learning with experiential education to engage the students’ entire body and mind and to open up to them the “real world” beyond the textbooks (Pedelty and Hamilton 89, 91). Although Pedelty and Hamilton found it difficult to replicate the face-to face, deep level of interaction that facilitates performance skills building online, the students benefited in other ways. For example, “turning the outside world into a digitally networked classroom” allowed students the freedom to choose the site and topics they are interested in, and learn from each other’s field based learning (Pedelty and Hamilton 92, 100). Cervera et al further propose “planetary performance pedagogy” via “digital companions and multipolar classrooms” for spatially and temporally distributed teaching and training in higher education. This approach “combines remote and experiential modes of interaction to facilitate an awareness of multiple planetary perspectives.” It also “reframes the planet as a shared learning environment,” expands the meaning of performance co-presence, and engages “sociopolitical asymmetries as core to performance classroom content.” Moreover, Cervera et al maintain “the interplay between synchronous and asynchronous teaching fosters and imagination of the world, and of the potentialities within in, that can invite the student to acknowledge their role in a planetary community, and therefore their own agency as part of it” (Cervera et al. 20–21, 25).

This description is apt for The Hunger Project, because the combination of asynchronous research and practice and synchronous brainstorming and presentation not only expanded the Environmental Art course learning space, time, and potentialities, but also allowed students to take a more active role in building the project in a multipolar manner. Although The Hunger Project’s online facilitation was unintentional, the process also enabled students to turn their everyday living spaces into a “digitally networked classroom”. Their learning became part of their other daily routines, and students could choose to collaborate virtually or in person for their artwork. As a result, the class as a whole enjoyed a wide variety of visual art forms on the project website.

It is worth noting that none of the artworks on The Hunger Project website are performance art. Instead, they are various visual art forms. This expands the understanding of taking action about hunger, which is often associated with performance and the actor/participant’s body in a physical space. Although there was no corporeal presence in the student artworks, their approach was creation and curation of images, objects, and texts. Therefore, The Hunger Project displays a different manifestation of hunger action. The students took part in hunger action through a learning process, during which they collected and synthesized information, and disseminated data, along with their reflections on hunger through visual translations. In this way, the performative aspects lie in its pedagogy and process-based research. In other words, the project is performative in its form of working if not necessarily its output.

The differentiation between “knowing that” and “knowing how” is investigated by Dwight Conquergood in “Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research.” He draws attention to the common binary between two domains of knowledge: “one official, objective, abstract…the other one practical, embodied, and popular.” The academic mainstream in the first domain adopts a “distanced perspective” of empirical observation and critical analysis, whereas the second one is “grounded in active, intimate, hands-on participation and personal connection.” Conquergood validates the latter, which he describes as belonging to the realm of “complex, finely nuanced meaning that is embodied, tacit, intoned, gestured, improvised, coexperienced, covert…” (146). In “Performance and Ecology, What Can Theatre Do?,” Carl Lavery also emphasizes the importance of embodied knowledge. He argues that text-based models of ecocriticism overlook theater’s “immanent capacity for affecting bodies, individually and collectively.” Moreover, Lavery suggests “the ecological potential in the rehearsal or devising process itself” (230, 233). It also connects to Woynarski’s belief that artistic and creative modes of engagement like theater and performance can lead to diverse ways of thinking about our relationship to ecology. “It is theater and performance that can employ and enact ecological thinking” (Woynarski 19).

Although the learning outcomes, the depth and breadth of their investigation into hunger, and the quality of the artworks varied among the student groups, as a general education final project, The Hunger Project achieved its aims: to guide students in the conceptual art process, in collaborative creation, and in hunger action. In conceptual art, the artwork stems from a core idea. In other words, the concept precedes the art object, and is central to the piece. Similarly in the online classroom, the pedagogical method led students to first identify the problem of hunger, then to collect and to synthesize hunger-related data and information, before responding through art creation. Compared to the more solitary nature of traditional academic study and field research for arts and humanities, this process has a shorter time frame, a virtual setting, and is more collaborative.

While archival/ethnographic research and essay writing often require a lengthy amount of time and library/site visits in person, The Hunger Project is more compact and suited for a 4-week general elective assignment. Understanding the problem, choosing a focal point, and brainstorming the artwork were completed in the first class session, the creation of the artwork, progress critique and discussion, and website building followed in the next three weeks, culminating in an online oral presentation in the fourth week. More importantly, The Hunger Project features collaboration among students from various fields of studies. Their respective training and perspectives make the collaborative process more interdisciplinary.

At the same time, The Hunger Project is characterized by an open-endedness and hands-on nature. While the initial research phase was rooted in real-world data, the latter part of the assignment relied on the students’ imagination and interpretation. Within the parameters of the assignment: create any type of art to address hunger, the students had ample room in the formulation of their artworks, whether it be method, material, or mode of presentation. The project also allowed the participants to practice translating their thoughts and observations, presenting pertinent social conditions, and conveying concerns for hunger through art creation. As a result, The Hunger Project pedagogy provided a new pathway to hunger action.

Through text and oral presentations, the students raised their peers’ awareness of various aspects of hunger, such as war and conflicts, human rights, access to health care and education, socioeconomic gaps, homelessness, spiritual longing and psychological needs, as well as agriculture and climate change. Many groups applied an intersectional perspective in their interpretation of hunger. Some went further to propose actions that could reduce hunger and promote food equality. As demonstrated by The Hunger Project, hunger action is not limited to the traditional understanding of performance, where the artist utilizes his or her body as the medium of the artwork. The project’s pedagogical experiment and process-based approach are performance. It is interdisciplinary, collaborative art creation as hunger action.

However, the incorporation of more performance art examples in the foregrounding phase of the project could enrich students’ brainstorming and subsequent creations. This could also help increase the students’ awareness of their role as both creator and curator of images and objects in performing hunger through art. The Hunger Project not only continued the social core of performance art by featuring hunger, a poignant problem, but also demonstrated the potential for hunger action through collaborative online learning and collective creation.

Babysitter. “Hunger Project.” The Hunger Project. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-4-of-spookynerd

Brookner, Jackie. “Rooting.” Ecological Aesthetics, Art in Environmental Design: Theory and Practice. Birkhäuser, 2004, p. 100.

Carson. Rachel. Silent Spring. Mariner Books, 2002.

Cervera, Felipe, Theron Schmidt, and Hannah Schwadron. “Towards Planetary Performance Pedagogy: Digital Companions in Multipolar Classrooms.” Theatre, Dance and Performance Training vol. 12, no. 1, 2021, pp. 20–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2020.1829694

Chaudhuri, Una. “‘There Must Be a Lot of Fish in That Lake’: Toward an Ecological Theater.” Theater vol. 25, no. 1, 1994, pp. 23–31. https://doi.org/10.1215/01610775-25-1-23

Cheetham, Mark A. Landscape into Eco Art: Articulations of Nature Since the ‘60s. Pennsylvania State University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780271081427

Conquergood, Dwight. “Performance Studies: Interventions and Radical Research.” TDR, vol. 46, no. 2, 2020, pp. 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1162/105420402320980550

Denes, Agnes. “Wheatfield - A Confrontation: Battery Park Landfill, Downtown Manhattan,” Agnes Denes, Works. http://www.agnesdenesstudio.com/works7.html

Department of Information Services. “Premier Touts Taiwan’s Human Rights Protections.” Taiwan Executive Yuan, December 10, 2020. https://english.ey.gov.tw/Page/61BF20C3E89B856/26083ff2-1bf7-49b4-9c0c-266988aab753

———. “National Human Rights Action Plan.” Taiwan Executive Yuan, May 18, 2022. https://english.ey.gov.tw/News3/9E5540D592A5FECD/db879e12-f6bb-46d8-ba80-851185c963dd

Douglas, Anne, and Chris Fremantle. “In Conversation: A Poetics of Empathy: Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison. Women Eco Artists Dialog Magazine, no. 13, 2022. https://directory.weadartists.org/in-conversation-a-poetics-of-empathy

Ecological Society of America. “What is Ecology?” https://www.esa.org/about/what-does-ecology-have-to-do-with-me/

Fun Jin Chee. “Shanghai Lockdown and Famine.” The Hunger Project. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-of-fun-jin-chee-1

FVS. 「張鈞甯、許光漢秒跪舔切割!大支宣布「絕對要買」H&M支持一波」, March 26, 2021. https://www.ftvnews.com.tw/news/detail/2021326W0191

———. 「台灣藝人急切割拒新疆棉廠牌 李永得提「人權價值」:這是價值選擇問題」, March 27, 2021. https://www.ftvnews.com.tw/news/detail/2021327W0019

Gablik, Suzi. The Reenchantment of Art. Thames and Hudson, 1991.

Get All Pass. “Falsity.” The Hunger Project. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-of-observation

Greenfield, Robin. “The Food Waste Fiasco: You Have to See It to Believe It.” https://www.robgreenfield.org/foodwaste/

Harrison Studio, The. https://www.theharrisonstudio.net/

Harrison, Newton, and Helen Mayor. “Hog Pasture: Survival Piece #1.” https://journal.tiltwest.org/vol4/harrison_hog_entry/

Huang, Zijie, and Xinlong Chen. 「因應武漢肺炎 相關業者面臨趕工加班」(“In Response to Wuhan Pneumonia, Associated Sectors Face Work Rush and Overtime”). PTS News, February 4, 2020. https://news.pts.org.tw/article/465131

Lavery, Carl. “Introduction: Performance and Ecology—What Can Theatre Do?” Green Letters: Studies in Ecocriticism, vol. 20, no. 3, 2016, pp. 229–236. https://doi.org/10.1080/14688417.2016.1206695

Lear, Linda. Rachel Carson: Witness for Nature. Mariner Books, 2009.

Leua, Jang-Hwa. 「跨域合作打造國家口罩隊」(“Establishing a National Mask Taskforce via Interdisciplinary Collaboration”). Public Governance Quarterly, vol. 8, no. 4, 2020, pp. 38–45.

Lin Hsin Meng, editor. 「新疆棉風波 蔡總統籲北京正視維吾爾族人權」(“Xinjiang Cotton Controversy: President Tsai Urges Beijing to Heed Human Rights of Uyghurs”). The Central News Agency Taiwan, March 26, 2021. https://www.cna.com.tw/news/aipl/202103260321.aspx

Manberdyni. “Hunger Project.” The Hunger Project. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-of-spookynerd-1

MyGoodness. “Hunger Project.” The Hunger Project. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-of-iridescent

Pedelty, Mark, and Joy Hamilton. “Further Afield: Performance Pedagogy, Fieldwork, and Distance Learning in Environmental Communication Courses.” Environmental Communication Pedagogy and Practice, edited by Tema Milstein et al., Routledge, 2017, pp. 88–101. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315562148-10

Roussel, Mathilde. “Mathilde Roussel: Hanging Living Grass Sculptures.” Design Boom. https://www.designboom.com/readers/mathilde-roussel-hanging-living-grass-sculptures/

Taoyuan City Government. 「防疫計程車隊發揮「有載無類」精神,承擔第一線防疫責任」(“Pandemic Prevention Taxi Team Assume Responsibility for Frontline Defence with Non Discriminatory Spirit”). City Governance News, Taoyuan City Government, May 14, 2020. https://www.tycg.gov.tw/NewsPage_Content.aspx?n=10&s=305343

Tate. “Environmental Art.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/art-terms/e/environmental-art

Thomas, Arden. “Ecodramaturgy.” Reading Contemporary Performance: Theatricality Across Genres, edited by Gabrielle Cody and Meiling Cheng, Routledge, 2016, pp. 200–201.

TOXICREADS. “Mr. Hunger.” The Hunger Project Website. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-3-of-spookynerd

United Nations Development Programme. “The SDGs in Action.” https://www.undp.org/sustainable-development-goals

Wu Ming Jou. 「拒新疆血棉花 台多位立委聲援受抵制企業」 (“Xingjian Cotton Boycott: Several Legislators in Taiwan Voice Support for Boycotted Companies”). Epoch Times, March 30, 2021. https://www.epochtimes.com/b5/21/3/29/n12843178.htm

XXTOBEJFXX. The Hunger Project Website. https://lilyweiglobal.wixsite.com/hungerproject/copy-of-fun-jin-chee