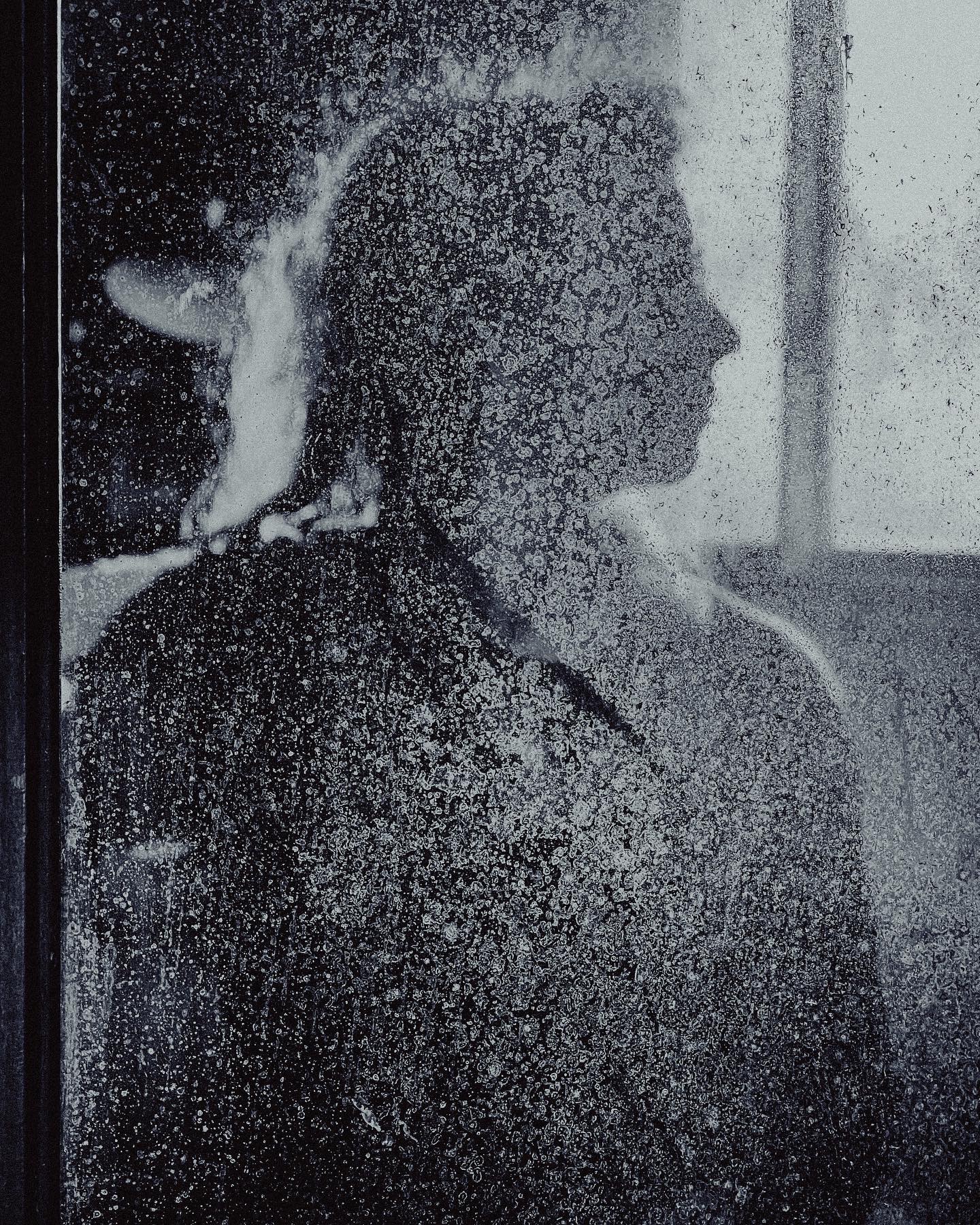

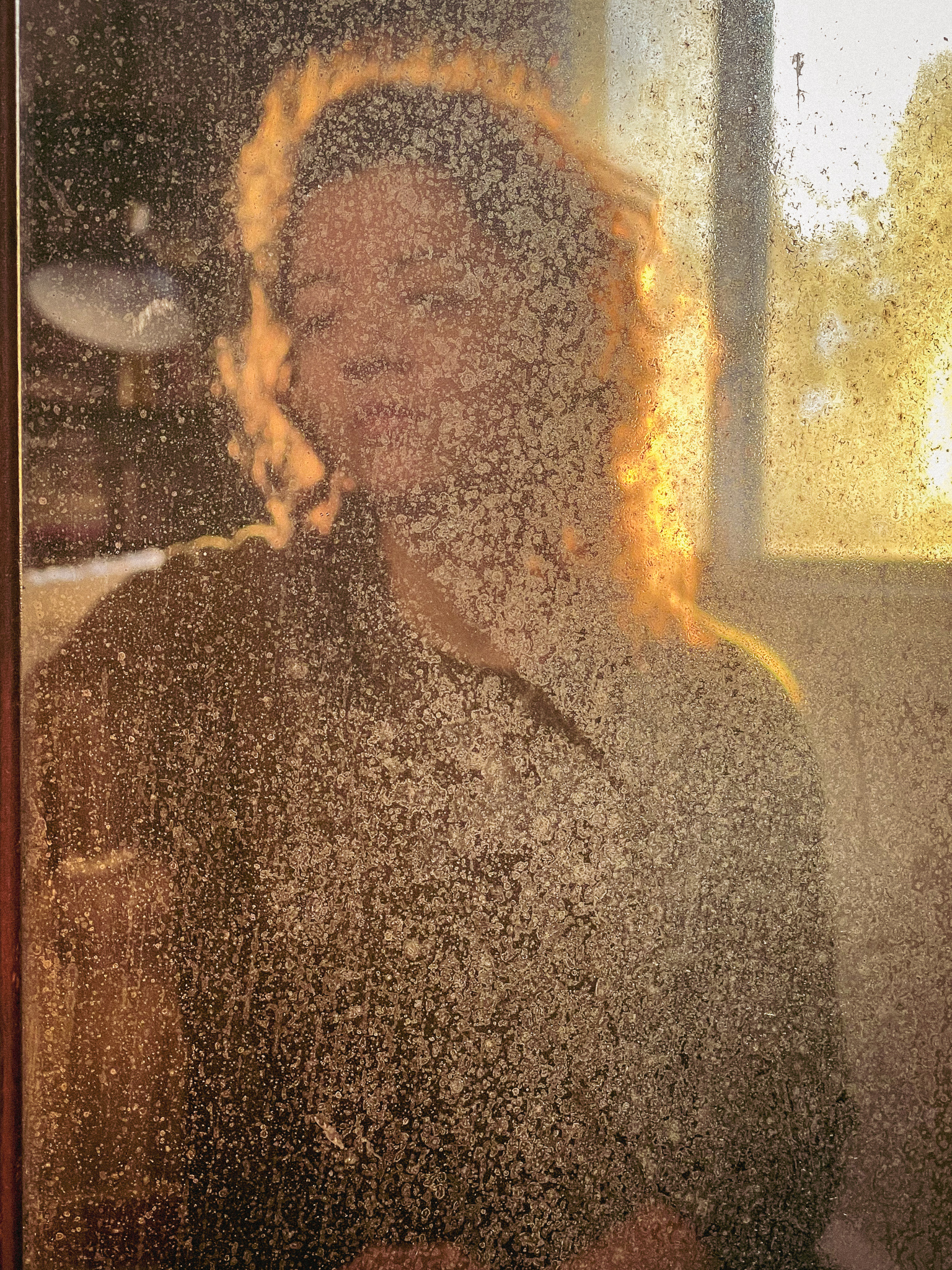

When I look into the warped, de-silvering mirrors of my living room, I see someone new every time; fragmented tableaux, occluded expanses of flesh dappled by mirror rot. There is nothing fixed about the body; it alters under environmental influences. Stress contorts me, relief expands me, disappointment shrivels me. I withdraw; I come back when the duress passes; I go retrograde once again due to some new issue. All visible, yet partially inaccessible, in these antique mirrors. It’s a looped vanishing act of flesh and muscle that only highlights the body’s presence and my responsibility to it. In this circuit of addition and subtraction, the whole system rings, stings, and babbles with unexplained, unspecified pain. The discomfort consumes one’s focus, even as one attempts not to think about the reality or responsibility of inhabiting a vessel that requires regular care; consistent attention. I stare at my face, and I see the grimace caused by the burning at the back of my throat and nostrils; oddly metallic and silvery. It tastes vaguely like the combination of a cup of black coffee and a burst battery.

While the back of the throat remains a raw, heated, charred location, the rest of my body is cold. Chronically, indefatigably cold. Cold like the glass, cool like the silver. Cool like my attempt to calm, self soothe. All of which is rather odd, because one is also too frequently sweaty; incredibly uncomfortable, sticky, frustrating. Being cold while being sweaty is, for whatever reason, humiliating; especially when all one is doing is sitting, staring, longing. Beholding what the framed individual in that antique mirror is offering. Perhaps it is the excess caffeine, but perhaps it is also that one is so tired, defeated, and moderately delirious from it all that the cold sweats are a signal that a faint is coming. Hard to say; then again, maybe not. I can see, in the silver reflection, how pale I become; blood leaves my face, returns in a patchy flush. Sometimes the flush is from the chronic pain. Every joint aches. More accurately, every surface hurts in weird, taut twists of muscle fiber. Is that a joint, or a tendon, or what? Knots upon knots from the stress of pushing the body beyond what it would care to do, thank you very much. The mirror reveals it: the way my shoulders are uneven, the way I sit crookedly because of discomfort. It is all right there. I am not able to unsee it.

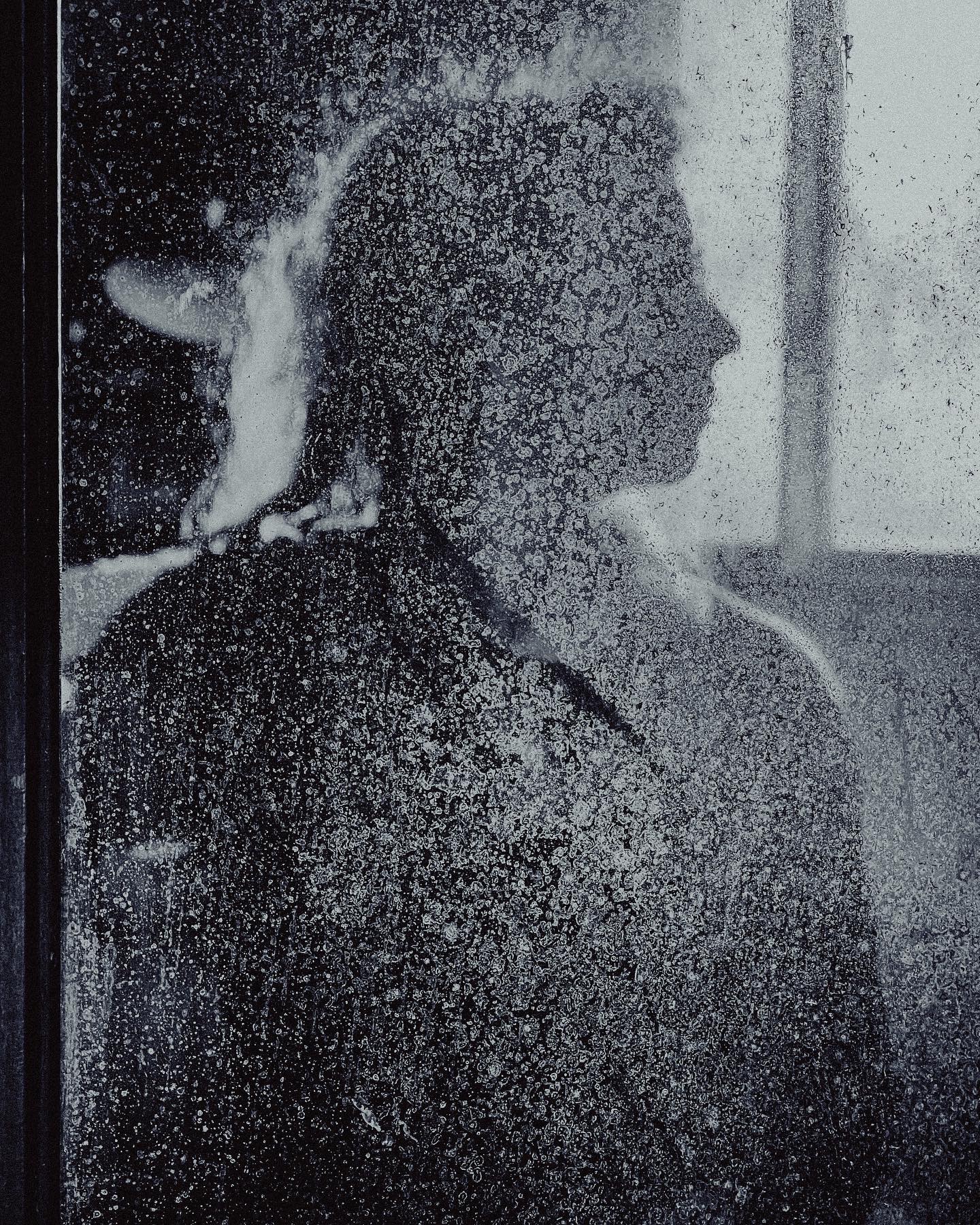

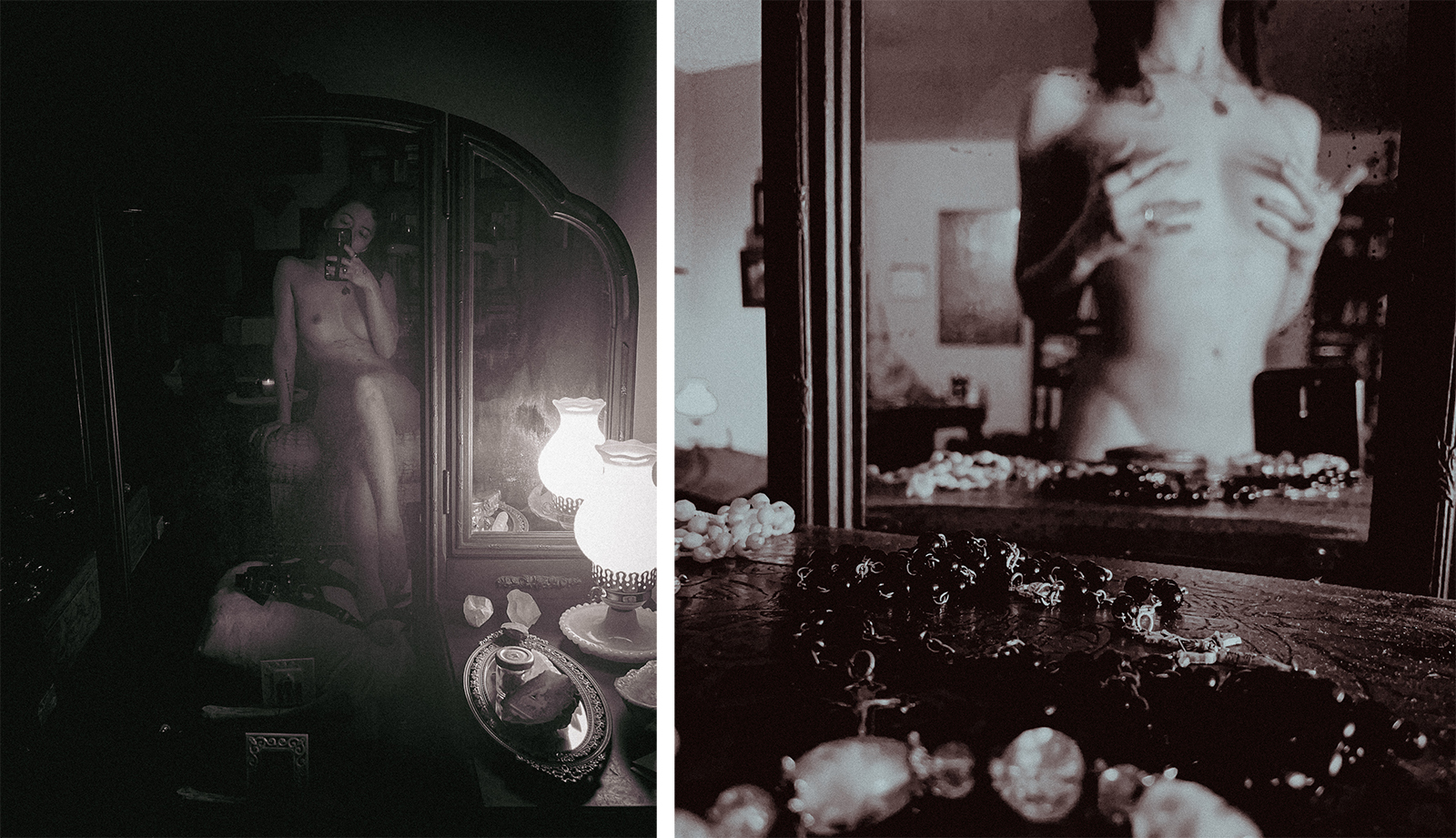

Purposefully, arousal becomes a dim memory while in this circuit of gain and loss. Despite how I may flirt with that reflective surface, suggesting desire as I take a photograph of myself that purports wanton abandon or is merely a bodycheck, I have at different times worked hard to suppress my body’s libido so as to eradicate the threat of desire. When one pushes the body to a certain point, the ability to orgasm is stolen from the form which aims to eradicate itself. Genitals and other sensitive spots on the body feel like aching bruises, and it hurts to wear pants, or anything structured; further support to abandon passion so as to remain “safe.” It’s hard to reach for that thing, desire, when the promise of joy and satisfaction appears to be a blatant lie or something wholly inaccessible. It has always felt safer to find a means to eradicate desire, than be disappointed by it.

These antique mirrors have witnessed much more than I have; silver tableaux of presence and absence. Fragmented moments of ascent and abstinence.

When I reflect on who I have been and what I have done in order to try and secure something safe, even if in that search I have severely harmed myself, I am equal parts mortified and grounded. Self-imposed starvation is many things, but most readily it is lonely. It is a specific type of loneliness that feels as bottomless and hollow as the pit of the stomach that requires food. It is as supremely sensitive as that stomach, so ill-prepared for any form of intake that it rejects attempts at nurture and care; just like the individual who becomes overwhelmed by affection and retreats out of habit. That being said, however, when I look into my desilvering mirrors I do not see someone who is unrecoverable, nor do I see someone who is in recovery. I see a warped image of someone who is more interested in understanding cause and limits than adopting the culturally desired recovery arc for the comfort of those around me. I am not a “warrior,” or a victim. I am deeply uninterested in inspirational labels that emerge from wellness culture, or “fighting” against my “illness.” I’m irritated by stories which suggest ruination or demand total recovery. When I look at myself, I see someone sitting at the crossroads; perpetually. I see someone who is fascinated by it all. I am keenly aware of how angry that makes people, my commitment to curiosity over disavowal. Folks tend to want recovery or nothing, but I cannot offer that. Not in the world we live in, not with the intersecting oppressions I experience—that many people experience.

What I am interested in is staring at that image before me and asking what is that? And why? If some form of comfort or “healing” comes from developing a deeper understanding as to why starvation feels like an appropriate response to exterior threats, then I am thankful. If understanding leads to new ways of operating in the world, alleviating suffering, then I feel blessed. Yet, through taking images of myself and committing to a memoir-practice and studying well-known micro-celebrities and memoirists who have become symbols of the unrecoverable and the bountiful gift of recovery, I have come to a place of frustration. I ask, especially within this memoir practice, what about sitting firmly within one’s current state, knowing that fully emerging out of “illness” or recovering from bodily disruption isn’t possible? What about refuting the ableist construct that in order to live a full life, one that is imbued with desire, pleasure, joy, and want, one must be completely “healed” or better first? There is value in writing from and generating understanding right where one currently is; “healthy” or not.

In this essay, I am presenting fragments, juxtaposing different means of existing publicly on social media platforms while using a memoir-practice. Here, I am detailing how these arcs of representation trouble, and are troubled by, a demand to recover. These tableaux of experiences emerge in the documentation and proliferation of YouTuber Eugenia Cooney, who has been widely condemned as unrecoverable; and the highly popular and commercially successful memoirist Glennon Doyle, who embodies the image of someone in recovery; and in my own documentation and relationship to my body through a performative image practice in a silver-rot clouded mirror. For myself, I define that the image and memoir emerge not as someone wanting a definitive answer, but someone who is seeking.

I argue that the diaristic writing generated on social media is an extension of memoir practice, and that the sharing of one’s image on varying platforms allows for discourse that bleeds into the auto theoretical. Posts are made to see oneself more clearly, to generate a form of capital related to the audience’s realm of concern, or to curate the image one wants to promote. Content shared by anorectics can generate broader conversations about the efficiency of the medical industrial complex and the subject’s own sense of agency within their suffering. Captions underneath the images, or comments on the posts, allow for various forms of reflection: to see oneself in the subject, to see loved ones in the subject, and to see larger cultural forms of oppression in the subject. These self-authored narratives disrupt a simplistic consumption of media surrounding anorectics. Their posts highlight the inadequacy of conversations dealing with self-starving behaviors, in the interpersonal and in the context of the clinic; especially when regarding joy, pleasure, and satisfaction (Pinheiro et al. 123).

Here, I will state that I am using “self-starvation” as a term for a broad range of anorectic and food-refuting behaviors. I am using it in place of labels provided by the medical industrial complex, by and large because I do not believe that using them here is helpful. These pathologizing labels do not encompass environmental, socio-political, cultural, economic influences and circumstances. They only define aspects and specifics of behavior. While my focus is primarily on a literal lack of appetite, I do not want to suggest that other means or causes of refuting nourishment are not present within the individuals discussed here, myself, or others. Additionally, using “self” may appear to presume I am insinuating total and complete agency of the starving individual, but that is not the case. I am using “self” as a prefix that sets this form of starvation apart from others, such as but not limited to: famine, state-sanctioned or because of natural disaster; conflict, or pandemics. For example: I made the regular commitment to self-starvation as a younger person so I could pay rent; terrified that if I bought groceries, too, I would further put myself in a financially impossible position. This choice, based upon my impoverishment, wasn’t exactly voluntary. That being said, I did have options for finding sustenance if I had chosen to seek them out, but on account of being completely and utterly exhausted and embarrassed by my circumstances, I did not. The prefix of “self” here indicates a more individualized set of circumstances and experiences, as opposed to something unilaterally oppressing my community.

For the sake of this essay, I will define memoir simply as self-authorship; a transdisciplinary medium between image generation and written word. Memoir is a means to offer fragments of the subject to explain an image one has generated to assert their personhood and existence (Fournier 13). Here, I am using the term memoir as opposed to auto theory, as I want to draw a distinction that I see between the two. Memoir allows for the expansive unpacking of a life and its fragments; glimpses of reason and purpose one can make out of their own narrative. It isn’t inherently theorizing in nature, which, I assert, does not diminish its value. Memoir is what Maggie Nelson describes as “life-writing,” more robust than diaristic work but less dense theoretically than academic or para-academic texts. It is “distinguished by its ontology as a practice…rather than a genre” (Fournier 14–15). In the context of self-starvation, social media has been an interface for a less formalized memoir practice by individuals who need to both reflect on their experience and feel the regard of others. It is a confessional space (Kephart 3). When I speak of an image, I do not simply mean the body as it is seen in a mirror. Nor do I mean the body, reflected in the mirror, as it appears on one’s phone screen. I see the mirror as something that produces the image and allows the individual to see fragments to better understand the whole. The subject is contained by the frame, by wood and glass or digitally, but it is that framing which allows for an unpacking.

Reflecting invites much. Reflecting on crueler ways of coping with broader disappointments and that which cannot be discerned when standing so close to a fragment of life, often obfuscates an authentic view of what the fuck is happening (Kephart 15). I believe that absolute clarity is not possible. The “truth” of our behaviors is malleable, and subject to change. It is difficult to discern what the “true” narrative of what that disappointment and greater pain is; an origin to chronic, cruel coping behaviors. Bodily pain and refusing to participate, to perform neutrality in the face of incredibly acute disappointment, makes more sense than stepping back into the world that so readily and aggressively falls short of one’s hopes and needs. All the same, if the individual decides to continue living, one eventually participates; one must. It manifests differently, but I remain that experiencing life and its broad scope of pain and pleasure is not reserved only for those who can stand and perform neutrality. Desire, pleasure, joy, and satisfaction do not belong solely to those who can cope in socially acceptable ways. I am sick unto death of simple narratives of being unrecoverable or recovering. I want more.

Self-authorship is the desire and claim of social media for innumerable subcultures. Self-determination through the hyper curation of an image on such an interface is a prime place for confessional writing about one’s experiences with disordered eating. Posting to social media at all suggests that the subject is interested in recognition and commentary. The writing generated in spaces directly addressing anorectic behaviors is often diaristic, flavored with a tinge of desperation, a yearning for being known, and a place to pour out one's heart. Even if these accounts are private, there is still an intended audience. Feedback and support are desired. Witnesses to the image one is curating and developing is desired (Rich 295). As Emma Rich describes in “Anorexic dis(connection): managing anorexia as an illness and an identity,” having accounts to display one’s curated image “may provide alternative spaces for these young women to voice their experiences without the threat of feeling pathologized. One only has to visit any of the web pages and support groups online to see that there is a concern from those who use these sites that without these contexts they would have no alternative space through which to share experiences” (295).

Visibility, even if constrained, limited, inflammatory, or fragmentary, becomes that which gives life to the subject. Memoir, as self-authorship, is a form of visibility; an antithesis to annihilation, even if the annihilator of the subject is the subject themselves. Regardless of its format, I believe the impact of such narrative-sharing is the same. The rest is just a technicality of process and platform.

Memoirs are often guided by the persona of the author. For the sake of this essay, I will define persona as the voice the audience encounters in a narrative. Beth Kephart states in Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir that the development of the persona through various writing practices not only teaches oneself the range of their own voice, but it can be a means to inhabit and transfigure facts about one’s life (32–37). It can be the intersection of the limited access one has to the subject and their curated image or personal branding. Persona may be a device to divulge some wisdom. Or, perhaps, the persona is used to simply offer up observations about the life the author is living; leaving value, meaning, and events open to interpretation by the audience. Memoir, as a process, holds space for all. That persona presents the image and voice of the narrative, and it curves and curls in any which way in order to create something that rings true; or true enough (Kephart 13). Accuracy of that story is subjective.

In the traditionally published memoirs I have tended to gravitate towards, the persona often demonstrates some form of a hero’s journey—something transpires, sparking a deeper evaluation of one’s life experience. The persona tends to offer wisdom from the journey, and thus becomes a reflection of curated fragments of the author and a much larger social inquiry. Especially in the context of revealing stories about self-starvation, traditional memoir often provides a vehicle for creating a succinct narrative. These works are passed through the hands of many editors, reviewed, edited, polished, redacted, and so on. Our new age of influencers and social media stars may not present as linear and neatly packaged a narrative, but the story is just as heavily edited. Content creators devote hours, or pay others to devote hours, to stitching clips together, adhering to a particular canon of graphics and music, revealing the personal within a particular light. Posts by social media users are not always perfectly uniform. It is self-authorship, after all. Social media allows a form of redaction unlike traditional publications. One can publish a post, and later edit or completely remove the content after it has been viewed widely by one’s audience. When it comes to how one governs their image, and the ways in which one desires to be viewed, the need to redefine, edit, and redact is as significant in traditional memoir as it is on social media.

Individuals who perform self-starvation and share it online self-author the experience of living in a body that is failing to “behave,” becoming a transgressive site for politicizing thinness. For the anorectic to share their story online is to “reject the medical model of passive suffering” (Cobb 2). Or, as Patrick Anderson puts it in So Much Wasted, “The surface of the self-starving body fully takes on the paradoxical significance suggested in the loss/resistance, for as it literally shrinks into oblivion it becomes larger and larger in vernacular of its political effects” (10). It is to refute the body as an inherently pathologized site, and to reject the anorectic experience as monolithic. These self-authored narratives live outside of the firm phraseology approved of by the medical industrial complex, and it holds a richness that isn’t discussed within theoretical texts or academic / para-academic spaces. Those who post don't even care all that much about grammar. The individual says what is happening; offers their perspective. Makes it plain, cryptic, raw, or simply divulges a wellspring of rambling thoughts; strung through by frustrations at their suffering, pride, or firm denial. Their content functions to generate a dialogue, sometimes involving the subject that posted the content, sometimes igniting a charged exchange between commenters. These exchanges perpetuate and add to the narrative that was outlined by the author. The more individuals comment, the more the post skews and reveals the general attitude of the subject’s audience. The readers of the post and consumers of the content signal their worry, their sympathy, their pity, their pleas for the subject to get aid (Swarte 6). The self-authored narrative is made more complicated because it is made public and social media allows for immediate, in-time feedback.

On social media, anorectic micro-celebrities openly struggle with the fragments they put out for strangers. That which generates their currency, gives them a name, clout, or any kind of recognition is typically the very thing which will eventually eviscerate their whole being. They will be but a name, haunting the internet with their lasting, starved visage and disappointed followers. Their ghost is kept alive by viewers wondering what happened to that person; frequent Google searches, checking on YouTube, Twitter, Instagram. They stay in the public mind by discourse in the comments: how could they go so far, how could they unravel so intensely, how the hell they didn’t perish sooner, how come they couldn’t get help, how it is so hard to believe their family allowed this, how they weren’t involuntarily committed, and on, and on, and on.

The micro-celebrity’s image will be stolen and proliferated across media platforms by others: a new video, channel, or account will pop up featuring all of that individual’s content, the context suspended. This is done for many reasons, but the consumption of the material is rooted in a desire to comment directly on the state of that micro-celebrity’s image. Viewers will hop onto third-party videos and denounce the micro-celebrity for their illness, making it know just how irresponsible they perceive that visibility to be; and to do all this without contributing to the original content creator’s ad revenue. These accounts take the micro-celebrity’s image and transgressive body and accrue a following, potential income, and social currency because of and as a result of that micro-celebrity’s slow, steady walk to death. The currency of the image will consume the subject, and the subject is reduced to the image.

What is that image?

And what is the power of that image when paired with the subject’s internal reflection; the context in-tact?

The morbid fascination with transgressive bodies and their availability on social media, such as on long-form content platforms like YouTube and Twitch, is unique to this moment. When I say transgressive bodies, I mean bodies that are perceived to be visibly different enough from the culturally produced status quo that the subject’s image becomes a site of curiosity for the general public (Swarte 6). The historic precedent for the ogling of such bodies, such as that of the hunger artist, paves the way for individuals like YouTuber and Twitch streamer Eugenia Cooney. This precedent not only enables her to gain an audience for the presentation of her transgressive body, but it allows her to market her image as a brand from which she gains social capital and a substantial income (5). Eugenia Cooney is, without a doubt, the most widely recognized name and figure of severe anorexia circulating on social media today. As a young woman who is as chronically online as any other twentysomething, I have grown up watching Cooney’s videos, wondering how the hell she hasn’t died yet. When I mention her name in a room, the immediate response from multiple individuals (generally speaking, typically femmes and/or folks with a history of body dysmorphia and disordered eating practices) is: oh my God, she’s still alive?

During her multi-hour streams, she has active conversations with followers. Sometimes she converses while performing demonstrations of viral trends, in other videos she remains sitting in her gaming chair, or opts to stand and walk around so that her outfit can be seen. In the videos, Cooney uses the depth of her room and proximity to the camera to accentuate her emaciated form. She stands at a distance from the camera in order to generate full body shots, showing off every angle of her body while pretending to accidentally reveal her underwear, breasts, or private parts (CooneyContent). Cooney will then get precariously close to the camera, her body becoming fragmented by her proximity to the lens (Love Eugenia Cooney, “Eugenia Cooney’s New Bikini”). Generally, Cooney is scantily clad, wearing mini-skirts with bra-tops; sporting an e-girl, emo aesthetic. In the close-ups of her body, there is the occasional clothing slip and a knowing smirk, followed by the firm denial in follow-up content of having done so on purpose. (Love Eugenia Cooney, “Eugenia Cooney Shows Her Avril Lavigne Collection Plaid Crop Top & Skirt”). Her alternative fashion choices are accented by the childlike room she conducts all of her filming and streaming in; the space populated with stuffed animals, anime merchandise, and poorly hidden bottles of Pepto Bismol (Cooney, “Last Minutes Slytherin Cosplay”).

The comments on her YouTube videos decry the visibility of her heartbeat through her chest, anger at her mother for not interfering, and how this is a grown woman who deserves no sympathy—I will note here that Eugenia Cooney is twenty-nine years old. The rage about Cooney’s refusal to outwardly own and admit to her complicity in the sexualization of her transgressive image through seemingly accidental slip-ups drowns out most positive engagement. This anger is, additionally, rooted in the fact that her audience is by and large adolescent people. She does not typically respond to these accusations or petitions to have her banned from varying social media platforms beyond denial of any wrongdoing while conducting her multi-hour streams (Swarte 5). At the time of writing this, in deference to her norm, Cooney has posted about being openly frustrated and devastated by the recent age restriction that has been placed on her TikTok account. The restriction has impacted her ability to generate income from the app, but also cuts off a huge portion of her followers. One third-party video which documented her crying on a livestream because of the ban, and there are many, has been viewed 36,260 times to date on YouTube (Keeping Up With Eugenia).

Through long-form videos and on livestream, Cooney commits to her firm denial of having a problem, all while knowingly posting her content with click-bait titles. Her actions actively enrage, ensnares, and ensures her audience. Cooney seems to be aware that her body’s deterioration is what gives her any audience at all. Her alarming thinness is her money maker. Her content may be about fashion and cosmetics, but on all accounts it can be presumed that Cooney knows that her true content is the spectacle that is her transgressive body (Swarte 6). The in-time interactions she has with her audience are conducted during live streams, on sites like Twitch, wherein people pay her money in order to send comments. An automated, robotic voice reads out the comment, punctuated by a cute burble or a cha-ching sound effect when Twitch bits are given. The comments are by and large different individuals begging Cooney to seek treatment, telling her she is going to die, or accusing her of promoting anorexia through her visibility on social media. I have sat in on her Twitch streams, watching people pay to hurl insults and demand that she gives up the ghost. It is perhaps one of the most unnerving things I have ever experienced; strangers yelling at a woman who is essentially the same age as me, dying slowly on a livestream for a paycheck (Love Eugenia Cooney, “Eugenia Cooney Crying Long Version”).

Her vlogging and streaming, though delusional in regard to the sustainability of her behavior, constitutes a contemporary form of memoir. Her self-authorship lies in the recurrent documentation of the veneer of the okayness she has generated, her refusal to own her physical decline or respond to the allegations thrown her way, and her curation of that image. Repeatedly, Cooney placates viewers in a raspy, squeaky voice that is tonally shifted upwards to produce something saccharine in quality. She states, “Oh, you guys, I’m fine. Really. I’m not going to die any time soon” (Love Eugenia Cooney, “Eugenia Cooney Says She Will Not Die Anytime Soon”). Unwavering “authenticity” is often the hallmark of a successful micro-celebrity, both in the content that they put out into the world as well as how they represent themselves to their audience. The image of the subject is their brand. Cooney goes against the grain of that expectation for authenticity, because her visible transgressiveness refutes a need to accurately vocalize her situation (Swarte 5–6). We can see it. Her currency is rooted in how she becomes an oddity, something of novelty and horror. She circumnavigates direct authenticity in the language that she uses, while also being abundantly authentic in the obvious deterioration of her form in front of the camera and her clear awareness of it. Oddly, it is supremely intimate. The fragments that the audience has access to reinforces the trap that is the image and the frailty of the subject. She is a contemporary hunger artist.

Cooney’s transgressive body, coupled with her hyper visibility, has led to other accounts appropriating her image by reposting fragments of her content so that individuals invested in knowing if she has died or not can check in without giving her ad revenue. These videos are given click-bait titles that are as provocative as Cooney’s, highlighting moments from her multi-hour streams in which she appears to be having a minor seizure, fails to do a push-up, or flashes her nipples. The comment sections on these stolen video clips are as inhumane, caustic, and sorrowful as the one’s on Cooney’s original content. The channels involve some scrambling of her name, such as but not limited to: Love Eugenia Cooney, Eugenia Cooney Archive, and Eugenia Cooney Twitch Clips. All are generated under the guise of being “fan content,” but in actuality act as a means to proliferate her image for their own social and monetary capital. Some videos cross compare clips of Cooney from 2019 to 2020, highlighting the brief moment in her decade long career as an influencer wherein she was involuntarily committed to a psychiatric ward and released at a semi-stable weight (Love Eugenia Cooney, “Eugenia Cooney [Before & After]”). It is the only time in Cooney’s vlog canon in which she is open about having been unwell or starving herself. Her voice is noticeably lower, her cheeks are plush, and she has a pink cast to her skin (Cooney, “I’m Back”). The contrast between then and her image in 2024 are haunting: her hair has grown limp and thin, her face is all angles and teeth, and her skin is marble-white (Cooney, “I’m going away for a while…Goodbye”).

The morbid curiosity in Cooney’s image, and the presumed inevitability of her death due to anorexia, is but one example of a larger cultural perspective on the visibility of those who are self-starving. The media surrounding the subject of Cooney highlights generalized beliefs about who deserves intervention and who deserves ire. Multiple YouTubers have produced pseudo-documentaries with harrowing titles such as The Dark Descent of Eugenia Cooney, a video which has viewed well over two million times; compounding those ideas (OnyxPink). Her deterioration and the proliferation of her image has provided individuals with the opportunity to generate think-pieces on whether or not she deserves mercy and aid; acting to dehumanize her and those who present similarly.

Cooney symbolizes the great, profound loss of someone who has opted out of their capacity to flourish in order to perpetuate and protect an image. As someone who has personally starved themself and demanded everyone overlook it, I can’t help but wonder what Cooney’s genuine response has been to the reposting and fragmentary, impersonal, and cruel productions that have been made about her. I wonder how she feels about the fact she has become the symbol of what it means to be unrecoverable: a moral challenge for her audience, yet beyond hope. Someone undeserving of graciousness, condemnable for being visible at all, yet undeniably beguiling for that very transgressiveness. Cooney’s “failure” to treat her condition has marked her as degenerate. Her disinterest in, or inability to, embrace “recovery” is perceived as a moral failing. Her refusal to conform demonstrates her agency, as well as her audacity. That, coupled with the fact that Cooney continues to live her life, creates a complicated, morbid fascination for her audience. Many want Cooney to be kicked off her platforms, others are curiously watching her and the rest of the audience, and some folks want to police her, forcing her into what they deem to be “recovery.”

Glennon Doyle gained a substantive, explosively large following from her lengthy blog posts that detailed her recovery from bulimia, drug and alcohol addiction, and Lyme disease in the aughts. She’s a more traditional memoirist, writing linear timelines of cause and effect, pain and redemption. Her works act as explanations for past behavior and invite readers to find their own redemption through self-actualization. Where Cooney represents the lure and fascination of the unrecoverable, Doyle embodies the glorification and attractive nature of recovery under capitalism. For the same reasons I am frustrated by the larger narrative surrounding Cooney, I am unconvinced by the simplistic a-b-c format of mainstreamed “recovery.” I appreciate Doyle’s honesty, and how much of her messaging is that being “in recovery,” and maintaining it, is egregiously difficult. I have personally greatly benefitted from reading her writing; it has made me feel less alone, more in-tune with my beliefs, angry at the culture I was reared in. All the same, her image and what emerges from Doyle’s social media platforms is an equation of recovery with success. Recovering publicly and succeeding to maintain an obvious state of recovery equals success in capital and social currency.

The book that propelled Doyle’s voice to the fore for autobiography was her 2016 memoir, Love Warrior, which sold approximately two million copies. 2020’s follow-up memoir, Untamed, focused more on Doyle’s critique of patriarchal conditioning, and it also sold over two million copies. Her podcast, We Can Do Hard Things, grapples with all the themes she raises on social media, in her books, and in conversations at live events. The podcast has 500k monthly listeners (Muck Rack). Her framing of food abuse as an addiction, a compulsion rooted in her deep discomfort in the world, has garnered a massive resonance; particularly for her reading base that is predominantly made up by cis women. Doyle’s established narrative of her struggle and her need to maintain food and substance sobriety are packaged and marketed as a classic hero’s journey. She starts as someone who is deeply troubled, behaving in ways that hurt those around her, herself, and her future prospects. In her first book, her call to sobriety and walking away from bulimia is rooted in her accidental pregnancy. The subsequent narrative can be summed up as a quest to retain sobriety, redefining her faith, and pursuing a means to live in her truth without dividing herself under societal pressures. In Untamed, her call to action is in realizing her deep intimacy and life discomforts, which caused her bulimia and addictions, are partially rooted in the fact she has been living heterosexually and is in fact a queer woman. The book details how she has settled into a comfort with sex, intimacy, and food, and she expands discussion to the ways in which she wants to prevent damaging conditioning in her children.

Arguably, the draw for Doyle amongst readers lies in her ferocious honesty and subsequent activism in recovery, but also that she symbolizes redemption for those who have lived as addicts. She is one of the most recognizable figures within contemporary memoir when it comes to conversations surrounding food sobriety and recovery, with more than two million followers on Instagram and over 970,000 followers on Facebook. As someone who has followed Doyle for nearly a decade, it is clear to me that social media has been the space in which she works out her larger ideas, engages with comments from her followers, and reconstructs those thoughts based on the exchange. Having read her latest book with that precedent, I recognized that there were whole sections of essays that were originally Instagram captions or Facebook posts. For Doyle, social media is both the place where she maintains and engages with her audience while working out fragments of her larger narrative.

A major theme throughout her oeuvre is the determination to stop abandoning herself for the sake of an image. Very much in the way I was raised, Doyle’s conception of goodness was once rooted in the act of withholding, making sure everyone else was made comfortable through routine division of her own self and the disavowal of her needs. Doyle’s marketed image, originally sitting squarely in a “Christian-mommy blogger” vein, has transfigured into a brand that demands radical action, service, and relentless critique of larger cultural systems surrounding and preventing true autonomy and self-authorship. Doyle’s brand identity and the image she projects is developed in and through her consistent reporting on her fragility; it manifests as persistent openness and frankness about the state of her recovery. In Love Warrior, she details at length how her early conceptions of sex, intimacy, and her value were rooted in the image she projected; in her words, her “representative” (Doyle 30). The division between her image and herself, she asserts throughout, was a major contributor to her suffering; a significant influence in her inability to retain sobriety from substances and food abuse.

Doyle’s determination to become in control of her conceptions of sex and intimacy, and to continuously develop her self-regard, are undeniably important and of value. In consideration of her “representative,” the false image of okayness that she developed at the height of her addiction, Doyle states that her goal moving forward is to always be one whole person, not two (249–250). Her desire is to collapse any space between what she is presenting to the world and who she is in private. Untamed takes Love Warrior’s themes further still, exploring how key components of her becoming are rooted in intersecting oppressions and privileges. She discusses at length how finally being comfortable inside of her body through becoming aware of her sexuality as a gay woman allowed her to ask why intimacy and self-image during sex had been so challenging throughout her life. Untamed is many things, but it is by and large a memoir about developing self-trust and a sense of agency within one’s desires for food, sex, and a right to flourish.

For myself, reading her books and following Doyle on various social media platforms invited me to begin asking why desire and pleasure were sensations that I fundamentally mistrusted, and how such distrust was not special to me alone. It also ignited in me a profound irritation that, as a person who operates in a less normative fashion, I must fight or be a warrior in order to express that agency, that desire. Despite the resonance I feel as a queer woman of faith, who has lived within anorexia and readily identifies with Doyle’s struggle, I remain unsatisfied with much of what her commercially successful messaging offers. While she does not assert it herself, Doyle is symbolic of a false promise of “recovery” under capitalism. To “recover” under capitalism means one inevitability becomes functional within the constraints of our society, that one can become marketable; is palatable. In recent years, Doyle has become more and more vocal about how fraught her own marketability is; a white woman leading in spaces that purport healing. I appreciate her own self critique and awareness of her position, and that she consistently aims towards intersectionality in what she writes and how she behaves. Regardless, she benefits greatly from her established image, the established narrative: under capitalism, buying into the grandiosity of recovery narratives, and then selling them back, generates economic and social success.

While I do believe that a less violent means of coping with the societal constraints we all live under can lead to great personal success, as damaging coping behaviors are self-defeating, I think that we all ought to be troubled by an underlying supposition: that identifying with “recovery” means one’s voice matters, and that living in a state of struggle, unwellness, or in the grips of something is not a worthy place to speak from. I do not appreciate our culture’s larger sentiment that, especially regarding memoir, to tell a story of being recovered is to have a decent explanation for why one was the way one was and also say but don’t worry, I’m no longer ill. I’m better now. Why is a label of wisdom granted only to those who state that they have “overcome it;” it being whatever trouble they struggled against. What about those of us who will never “be better” or recover in a way that is socially acceptable? Why are voices, possessed by those who are standing at the crux, not just as valuable as those who have stepped through a threshold into something marketable? Should not perspectives from gray areas be viewed as just as worthy, just as significant?

I am aware that it makes people angry that I don’t immediately disavow anorectic behavior as a wretched, awful illness that needs medical intervention. When I tell people how it has, in very tangible ways, harmed and irrevocably altered parts of my body, that anger is further inflamed. Upon hearing my history, folks want a solution. They want me to tell them about my redemption arc, my recovery, my success. There is a strong desire for me to tell an uplifting story about how I used to be one way, and now I am another, so that my writing provides a feeling of comfort for the reader or my interlocutor. I cannot offer that, by and large because I have not “recovered” in the way folks want or expect me to be. Regardless, I believe my voice, as I stand before the mirror and write about my experience, has value now.

When it comes down to it, I know how I could have behaved differently. I did not necessarily need to starve myself in order to cope with the difficulties of my life, but I only know that in retrospect. In the moment, I behaved in a way that was utterly predictable with my upbringing, my conception of goodness, my situation, or in my frustrated, vexed mixture of wanting to be known and wanting privacy. Self-starvation is as personal as it is symptomatic of something cultural. The image production and writing practice surrounding my own experience has been the means through which I have begun to understand fragments. It has been a way to unpack internalized ableism, but also refute established narratives surrounding anorectic responses to one’s environment. Dealing with my reflection has enabled me to consider aspects of my behavior in a fragmentary way, regard my image in snapshots, and understand the days as isolated experiences and systemic. Memoir has allowed me to see a circuit; reflected in silver. It is the writing of these fragments, the documentation of quiet moments, which helps elucidate the whole. Writing offers context for the image of the subject (Kephart 10).

Allow me then, further context.

2022 brought me reflective surfaces dappled with silver, tarnish, and an occluded sense of proportion. The mirrors I keep in my home are imperfect. They are all antiques; murky, difficult to see oneself in, literally warped. This is not fueled by body dysmorphia, but more so a deep disinterest in seeing myself clearly all day long. I see myself enough, thanks. They operate to reflect light in my dark apartment, to add an ambience; more aesthetic than functional. The main mirror set I use is a vanity I have from 1922; the glass is original to the piece. It dominates a whole wall in my living room, and there is no place one can sit without catching a glimpse of themself in that mirror. The vanity’s wood is dinged, and the trim surrounding the glass is cracked; whole sections missing. The mirrors are desilvering because of damage and exposure to moisture. This appearance, also known as foxing or mirror rot, will one day completely obscure the reflective surfaces. Their tin and silver backing, enabling the reflection, will eventually eradicate any clarity. That which allows for any reflection at all is also that which will eventually consume the image.

When I spend time staring into these mirrors and gazing at my ever-shifting form, I think about that. In the reflection, I see something fragmentary and limited, but revealing. During the spring of 2022, shortly after obtaining this vanity, I went through life changes that engendered the most extreme distress and grief I have ever experienced. Grand intersections of loss, death, and the subsequent abandonment by my then partner sent me into a psychological backbend that I still feel, muscle deep. I don’t mean that in a romantic, poetic capacity. My reaction to grief led to a food sabbatical that weakened my muscles and joints, resulting in muscle tears that I have been forced to actively pursue medical intervention for. This is not the first time I have responded to extraordinary disappointment by abstaining from all things; food, pleasure, and so on. That is perhaps why this time around it has been such an unforgiving process as I work my way back towards stability. 2022’s food abstinence was different; I knew myself in a more pluralistic way than I did when I first began starving as a means to cope with how difficult my life could be. At twenty-seven, I knew the rhythm for a cycle of self-starvation; the ups and downs, how to veil it, how to hide it, how to remain functional. At twenty-seven, my body signaled to me that it no longer tolerated nutrition sabbaticals in the same way it used to. In fact, it wouldn’t tolerate it at all. I went from functional anorectic to completely destabilized so quickly, I shocked myself. I scared the hell out of myself. I’ve fallen apart before, but never with such severity, or so quickly.

Another major difference was that, historically, my cycles of starvation have been rooted in a desire for utter abstinence. Abstinence from all that could be taken into my body, come from my body, or be experienced by my body has been my modus operandi in order to cope with bouts of extreme stress, failure, and loss since I was a child. This has included abstinence from food, pleasure, desire, and somewhere dappled amongst it all, responsibility. In 2022, as I disappeared into immense despair, I was fascinated by how, more than ever, I wanted to find a way to believe I had a right to take up space. I had something in me that couldn’t be starved out for once: a profound and deep need to desire and be desired, despite the expanse of my disappointment, of that grief. Especially due to the nature of the losses I was experiencing, I didn’t believe that absolute and utter abstinence from life would be the thing that carried me through this time.

I arrived at a crossroads: this coping method was no longer viable if I actually wanted to keep living and participating in the world.

I desperately wanted to exist. I still do. I was frustrated by my old means of processing, where I demanded my body behave, but actively worked to refuse sustenance so that it could. I wanted to be free of my body’s needs, I wanted to be left alone- by society, by my body, by disappointment (Anderson 37). Something had shifted in me from my youth, wherein what I knew intellectually was blooming in me emotionally: complete and utter abstinence from the world does not make one safe. Starving human desires out of myself so as to not be “distracted” does not make me safe. All I have ever wanted is a sense of security and safety. Susie Orbach explains that longing quite succinctly in Hunger Strike when describing motivations within anorectic behavior, stating, “We can begin to see, then, that the cause she has taken on is that most precious one: the creation of a safe place in the world. She is trying to legitimate herself, to eke out a space, to bring dignity where dismissal and indignity were rife…Her self denial is in effect a protest against the rules that circumscribe a woman’s life, a demand that she has an absolute right to exist” (qtd. in Anderson 36). I’m a very passionate person. I tend to feel deeply, and trying to find a way to cap that and make that passion less intense has often been a requirement for my daily functioning. The abstinence I am speaking to is a result of having strong preferences, powerful inclinations, and very clear desires, but being absolutely terrified to feel or experience them. Disappointment and loss have always been more painful than simply opting out, and when disappointment has been a norm, it becomes logical to search for a way to make oneself feel safe from it.

To cope with the simultaneity of this newer understanding and trying to work through an older means of processing pain, I established a self-portraiture practice coupled with a daily writing regimen. It was a means to keep myself invested in the mortal coil as I struggled with the fact I was quickly disappearing. Over the course of several months, I took a few hundred self-portraits in the antique vanity mirror to try and reconstruct my own perception of my image. I wrote over two thousand words a day. I wanted to find some means to hold onto the subject through documenting the image; making sense of the image I saw before me in silver and my inner life. Then, I worked at collapsing them into one subject through memoir. The image was lensed, posted to a social media platform, and ruminated on further; a distillation of a raw moment in time that has been filtered and edited within an inch of its life. I framed the context of the image; nestled it within captions which acted to suggest more than directly inform. It was more life-writing instead of the theoretical; incredibly valuable, regardless.

Difficult to visually access due to mirror warpage, desilvering, and editing, these self-portraits made me hyper-aware of how the behavior that is generating the subject’s image will eventually consume the image and the subject. Self-starvation consumes in a literal sense. The body, its desires, its drive, its ambition- all of it is lost to the image, the apparition in the mirror. I refute the reductive narrative that self-starvation all comes down to body image. Yes, body image can be a genuine motivation to disappear oneself, but it is not always the whole or origin point of self-starvation. The power of the image, the subject generating the image, and the multitude of damages surrounding the two, are acting in tandem to eradicate and harm the subject. These are intra-acting agents.

Most of these images and the several fragments of this writing found a resonance with my curated audience; comprised almost exclusively of queer femmes, mostly lesbians. Especially amongst queer folks, there was a profound camaraderie in how desperate I was to redefine an image of want for myself. In the face of such extensive loss, amidst a spiral into anorectic behavior to cope, there was even more support, more understanding, and true respect for the journey. I am beyond thankful for those who read my writing, who commented on my pictures, who found me desirous, helped me see my own desirability, encouraged me to pursue my sensuality. It is through posting my visual reflection, and my internal reflection, that I gained depth in regard to my own definition of seeking and desire. And, most certainly, it heightened an awareness that such a need for redefinition, especially as a queer woman and as a chronically ill person, was not unique to me. Many of the images are portraits of my body; desirous, wanting, unapologetically horny. It became important to me that I create images of want, because my original coping mechanism was abstinence. I named this series of images in reference to Carolee Schneemann’s Fuses, wherein I made overtures to exhibit my arousal as something supremely neutral, normal—specifically as someone in possession of a body that is chronically unwell.

The images of my body in occluded silver glass range from the erotic to the irreverent. Some of my portraits are mundane; fully clothed and enjoying the sun streaming in through the window. Others include my naked form posing with a strap-on, holding flowers, freshly showered, showing off a kink collar, recovering from pneumonia, and so on and so forth. They are simply documents of my life; my shrinking, growing, and shriveling form. Simple. Pretty, enjoyable, and simple; thank God for that. The documentation of my body became performative wherein even if the emotion or lust had been expunged from my body due to starvation, I was dedicated to generating imagery that genuinely aligned with a growing understanding of my own sensuality. The portraits are of a frustrated body, true, but it is one which refuses to perceive lust and want as something only accessible to the well-adjusted, the healthy, or the “stable.” I am in possession of a body that has been abused, by myself and others, and doesn’t “work properly,” but still demands a right to express want, to feel wanted, to be desiring.

My anorectic body has been many things, and I will perhaps never be someone who manages to create a memoir that espouses my grand, heroic redemption arc. I will never be perceived as unrecoverable, but I am also fully disinterested in producing a commercially successful recovery memoir. I do not believe I should have to be “completely healed” in order to live a full life, nor do I believe that all worthy stories must have the hopeful resolution of being “healed.” I know of no person who is completely any one thing. There is value in writing and documenting from a place that sits at a crossroads, especially one in which starvation has left the individual permanently altered. There is no going back or moving on. In my life, starvation has been how I have coped. Coping of any kind has consequences. My consequences are what they are, and I am not ashamed of that. I don’t think my story ought to be one of warning, or an example of what one must not do. It is simply my own.

When I start to slip into a state of starvation, often entirely unconsciously, I now take it as a signal; an alarm bell going off. It is information about my current state of affairs, not damnation of my whole being. It is a reaction which tells me I am not getting something I need. Here, I am speaking from experience, but also from a place of private discourse with others who have navigated “recovery” from self-starvation. In recovery or treatment for self-starvation within a clinical context, it often feels like the only time that sex comes up is when someone is inquiring about how devastating they presume it to be. As Dr. Andréa Pinheiro bluntly states in the introduction to her study ‘Sexual Functioning in Women with Eating Disorders,’ the sexual functionality of those with disordered eating patterns “is rarely discussed as an important component of treatment except in the context of sexual abuse and trauma histories” (123). Seldom, if ever, is that individual asked about pleasure or their ability to experience it. The clinic could be said to be just as distracted as the general populace by the image, forsaking the dignity of the subject. Anorectics aren’t asked about if they have desire, or if they are averse to conceptualizing themselves as desiring. They are not asked about seeking pleasure and satisfaction at all, or if they perceive themselves as being someone with active sexual agency for the sake of their own pleasure. They are asked if they can maintain a regular period or sustain an erection. That is not the same as an ability or the wish to experience pleasure. That is not the same as having desire. Anorectics are presumed to be fundamentally divorced from being desiring agents; incapable and abstinent in all things, regardless of where they are at in their own process.

I most certainly was not asked by medical professionals if I trust in the idea of satisfaction. I often wonder if folks are asked if, conceptually, sexual satisfaction seems like something that could be an accessible reality—or, if like food and the expression of genuine feeling, does it seem unsafe? Unpredictable, untrustworthy, unreal. Within the context of the clinic, sex becomes something that the anorectic obviously could never desire, since of course, they are afraid to take in sustenance, let alone risk taking in another body. That isn’t even on the table; that individual’s pleasure, their conception of want. In the pathologization of the anorectic, in many regards, their dignity is stolen; their world made small, and their behavior reduced to illness. It is as if that individual’s access to pleasure or right to satisfaction is given a back seat because they are perceived as being so lost that joy and desire should not, and could not, be an objective.

These sentiments carry over into conversations around and from other folks who have transgressive “misbehaving bodies,” such as those who are disabled, and find that their experiences of yearning or lust are, too, dismissed (Shah). The general energy from the medical industrial complex and society is: But you don’t work right- how could you possibly possess lust? Desire? Shouldn’t your whole focus be on how ill you are? Such a sentiment, or the implication of it because of the way the medical system views anorectics and other folks who “don’t work right,” both paternalizes “misbehaving” bodies and disabuses the notion that such folks may have a very clear response when it comes to what they want, that they may possess desire, that they are very capable of pleasure. For anorectics, there may even be a strikingly clear answer as to why they behave as they do, and in the face of an unpredictable, painful world, such withdrawal feels like an appropriate response. Further, such starving activities may be in response to having a yearning so crystalline in its clarity, that the urge to starve it out feels like an appropriate choice due to a lack of access. Yes, arousal may vanish in the face of a profound calorie deficit, but arousal and the ability to orgasm are not the whole sum of want and yearning; “finishing” is not the whole of sex. Amidst it all, there may still be a blatantly obvious preference in sexuality and desires. Dr. Sonali Shah writes that cultural, recurrent exclusion of disabled and misbehaving bodies from discussions of sexuality often lies in the discomfort of able-bodied persons surrounding the individual. Those with power in the disabled person’s life—family, teachers, and medical professionals—would rather buy into the cultural script that such non-normative bodies are inherently asexual. Presuming asexuality in the face of a misbehaving body is cruelty, and it is a disservice to others who actually identify as asexual. To presume asexuality is a result of illness, and to presume the ill are only ever asexual, is violence and erasure.

The everyday, mundane aspect of sex, pleasure, and satisfaction ought not be conceived as a special treat, or something like the final hurdle of wellness. That is ableism. Presuming health as the ultimate goal, a moral good, in a world where the definition of health is rooted entirely in cultural constructions that reinforce and upbuild institutional prejudices is wrong. One should not have to “prove” they are healthy to have a right to pleasure, desire, or the expression of it. Simultaneously, the subject ought not be reduced to only the image fragment, wherein the projection of sexual availability by the starving micro-celebrity is their sole means of generating ire-ridden engagement for the ad revenue. The policing of bodies in this capacity helps no one.

Desire and pleasure troubled, difficult things to access when one is inherently distrustful of satisfaction. Within bouts of self-starvation, I’ve been particularly skeptical of satisfaction, because it always seemed to be something that one briefly tasted before everything fell apart. Being afraid of satisfaction felt, and often still does feel, like an appropriate response. Withdrawal or utter abstinence has always felt safer, especially when the engrained understanding of emotional levity is that it will disappear again; teasing me instead of offering genuine, lasting relief. It takes substantial work to accept, and not feel crushed by, the fleeting nature of satisfaction. Coming to understand it as inherently temporary allows the individual to believe that pleasure and satisfaction operate as an invitation. Joy transfigures from the disappointed, false promise of “never again suffering” into a balm for the senses that must, over and over, confront how very bruise-able they are. Just like hunger, satisfaction can be both a weapon and a tool to construct and deconstruct how one moves through the world. Where any state of permanence in mood or temperament is desired, including states of being “fully healed” or “fully recovered,” only severe disappointment can follow. And disappointment can bend the will and spirit so far back, one’s joints can crack under the force.

In my own life, self-starvation has been the means by which I’ve clawed through some of the most horrific seasons; a behavior designed for white knuckling profound disappointment. Here, I hope to further disrupt simplified narratives surrounding self-starvation, wherein anorectic behavior is reduced to only a difficult relationship to one’s image. I have starved myself for many reasons: I have starved when I had no money and couldn’t afford to feed myself. I have starved to negate desire, to try and keep it at arm’s length so I didn’t feel the false promise of satisfaction where there was none to be had; knowing the exact number I needed to whittle myself down to so as to eradicate lust. I have starved to stop my period, because I couldn’t afford menstrual products. I have starved to try to make myself feel safe, to generate an aspect of gaunt undesirability, after being violently sexually assaulted. I have starved myself because, after a different sexual assault, the idea of taking anything in, in any form, immobilized me. I have starved myself because my ex told me that I couldn’t ever sexually satisfy them, and the sheer embarrassment made me want to die. I have starved myself because, in that same conversation, they ended our relationship out of irritation at my inability to cope amidst a season marked by the deaths of so many people that I loved; making me, too, want to disappear. I have starved myself as a profound stress response, because I knew from previous experience that it helped me feel in control. I have starved because I didn’t feel like being here, operating in any capacity in the mortal coil. I have starved because of indifference to my body. I have starved because of disinterest. I have starved just because I could, damning anyone for trying to stop me or interfere in my business. I have starved myself for extremely serious reasons and relatively stupid ones, voluntarily and involuntarily, and without fail I’ve looked into the mirror after it all, moderately baffled, and asked how are we here again? The great stress or horror or fraught moment inevitably passes, and I, too, yield. I relinquish the death grip I have on caloric restriction. I hold out a shaky hand for something neutral or bland to consume, and I carry on.

I know such behavior is not fair or acceptable to those who care for me. Bearing witness to such behavior is damaging in an entirely different way. So, like many individuals, I have done it quietly and with multiple roundabouts so as to keep it as private as possible. I have asked people to overlook my state by saying, like Eugenia Cooney, that “I’m fine.” It is behavior which aims to defend the self against false promise, but it is also behavior which negates the balm which may offer the building blocks to genuine, lasting relief.

To choose self-starvation is to decide upon a specifically agonizing type of isolation, in that one is no longer performing in tandem with the community at large; pursuing life-sustaining and perpetuating operations. It is to opt out and refuse expectations and requirements for life. It is to say for fuck’s sake, I have had enough. Within self-starvation, there was an affordance for and means to manage the ways in which I felt brutalized by my life and its situations. Ultimately, it was and is addictive. It has offered relief in ways that few other things did, and it was more affordable than any other vice or doctor I knew of. When looking at the fragmentary aspect of my long standing writing practice, reflecting on all that I have done to myself in order to endure, I am able to see the ways in which my behavior was a means to govern my image and generate a narrative that explained why I was the particular brand of off-putting, starving, and upset that I happened to be.

Now that I am older, I have begun weaving these fragmentary tangents with more purpose, steadier resolve. I reflect, I gather the old understands and the new, and I suture them in text so as to tell my story; to connect to the stories of others. I see value in generating a timeline, suggesting a reason for my behavior. Yet, I also assert that I shouldn’t have to explain it, define any absolute reason, make my suffering understandable and palatable, for others. Anorectic behavior is not unique or new; I am not special. I am both horrified and relieved by that conviction. Social media platforms continue to be a vehicle for understanding something personal and cultural: a space to reveal, share, and confess. It allows others to see the image the subject decides to generate so as to be made known; to feel the regard of another in the narrative one develops.

And I am seeking something, always. Understanding of myself, but also of others, as I walk hand in hand with folks who have turned to complete abstinence from all things as a stress response, as a reaction to feeling completely unsafe. I am not yet convinced of any resolution that demands absolutes. I’m interested in gray areas, in crossroads. I am only invested in the moment, where I stand, and the different arcs that I could or may pursue as I move forward; knowing I can never really move on from what I have done to myself. I gaze into a desilvering mirror, and I know who that image belongs to. I know who I am. I know what I can no longer permit myself to do in response to disappointment. I know that, in the depths of the repercussions of self-starvation, I have gained a different perspective than that of many people. In being unwell, I have begun to understand just how dangerous the glorification of recovery narratives are. And, in seeing the bounty of how improved my life has become as I find other means to cope, I understand that I cannot sit at the same crossroads forever; redefinition will not allow it. Thank God.

My refusal to condemn anorectic behaviors as an uncategorical evil and illness sparks rage in people; especially those who have experienced the pain of self-starvation firsthand. In one such instance, where I broached the idea that discussions around pleasure are not adequately integrated into recovery programs, I had it said to me by someone who’d undergone treatment for disordered eating that they couldn’t possibly focus on sex or pleasure when they were at their worst. They “were just trying to survive.” I respect that statement; wholeheartedly. I want to honor and hold space for folks who define themselves as recovered, or in recovery, or are actively working towards eliminating all self-starvation behaviors from their way of life. It is debilitating to have starvation as an internalized, automatic response to distress. Obviously, it isn’t a coping strategy I would recommend to anyone. I want to state here, in no uncertain terms, that I respect the choice to treat anorectic behaviors as an illness that requires medical intervention. Seeking treatment for that behavior and finding doctors who are uplifting is a noble thing, and I commend any person who goes that route. Medicalization of anorectic behavior can and has saved lives, altering them for the better. I would never deny that.

But the only thing I could think when that was said to me was: but what do we survive for? To just make do on principle? To just keep going, because to not do so would be immoral? Towards what end? Why must I be completely, utterly, irreproachably “healed” in order to be permitted a right to experience pleasure? Discuss it? Negotiate it? Unpack it? Especially if my relationship to pleasure is that which is causing me the debilitating distress in the first place? What is the purpose of “pulling through” if along the way there isn’t a possibility for satisfaction in the broadest definition of that term; meaning with food, with ourselves, with sex, with pleasure, with desire? If the issue at hand is profound dissatisfaction, and a frustration that prevents flourishing, then isn’t the disbelief in the accessibility of those positive feelings that which needs to be surmounted? If, like me, there is permanent damage done to the body that cannot be categorically “healed,” does that mean I am relegated to merely surviving? Why is “health” the prerequisite for pleasure and joy?

I am personally deeply uninterested in just surviving, I desperately want to taste that which makes life worth existing for. When I pursued medical intervention for my behavior, I found myself in a place darker still. It was not the right move for me, because there were no doctors or specialists in my area who could serve me. The medical labels did nothing to help me; they only condemned me. Medical access across the United States, especially for mental health concerns, is not equal. It is markedly less progressive in parts of the Midwest, especially where I am from. In Iowa, I was told I didn’t qualify as anorexic, because my goal wasn’t to lose weight. I was instructed to make more friends, to get out there, get some sunshine, and to try and meet someone romantically. In utter contrast, when I sought medical aid in Wisconsin, I was told that it was on the table that I would be involuntarily committed if I didn’t agree to beginning an antidepressant medication immediately.

I don’t think either of these responses from medical providers are the right one.

What if, instead, it was asked how one may be invited into perceiving pleasure, satisfaction, and desire as something that sits among one’s inalienable human rights? That it is all actually a mundane, ordinary experience? I wonder what would happen if the questions asked by medical professionals or the general public were not centered around what is wrong with you, but instead: what would make satisfaction seem plausible, accessible, and safe to you? What would help you believe that satisfaction and pleasure is not a gateway to disappointment, but just a part of being human? Looking at self-starvation more broadly, it can be appropriately identified as a response rooted in wanting to carve out a safe place in a radically painful world, wherein disappointment abounds. It is a means to not take more of it in; refuting glimpses of contentment that create deep, aching reminders of long-term satisfaction’s inaccessibility (Anderson 36). What if we were culturally committed to rejecting the grandiosity of recovery narratives wholeheartedly, and simply examined where one was at, and honored that voice, as is? What would happen if complete recovery was not the goal, but instead we oriented support for anorectics towards providing tools to live a dignified existence while within it, working on it, and maybe through it?

Reducing the anorectic to a number, a statistic, or someone who needs to be further regimented and treated as a problem, suggests we do not have a right to mundane, everyday joy, such as sexual satisfaction. It suggests that we do not understand what we are doing, or that our situation is one that isn’t generated by complex, intersecting oppressions. To impose the term disorder on someone who operates against the grain has the great potential to cause deeper harm (Caplan). The clinic presumes absolute authority on what health is and what normative behavior is, but it’s not without cultural influence. Nothing happens in a vacuum. What could occur if we revoke the categorization of such behavior and omit a loaded label that condemns and deems the individual as someone who is inherently unwell because of a cultural prescriptive on what health is?

Memoir offers reflection. Memoir offers self-regeneration through a deeper, plumier understanding of the subject. Memoir offers a document that establishes that the subject exists beyond the image; it provides context. While my desilvering mirrors will eventually be entirely lost to the void as they become eradicated by age and exposure, the fleeting reflective surface has become permanent and recorded in the form of written memoir. The image has been documented, edited, and shared. I will not yield and be crushed by the expectation of branding that fragmentary reflection, dividing myself into subject and image. I am able to shift and change, the fragments evolving and devolving in tandem with the narrative I provide. The language, adding context, will only ever become richer from that fluidity; the reflective nature of memoir making the subject more than a vapid, curated veneer fit for public consumption. It is that internal reflection which allows for the possibility of satiation. The refusal of division is what will ultimately allow me to do more. The refusal to bend and commit to a simplified narrative that holds recovery above seeking allows for so much more.

And that’s just it.

I want more. I want more. I want more. I want to maintain the subject, salvage her, for as long as I can. I want to tell her story from where she currently is, I want to seek, and I want to reflect. I sit in front of silver mirrors, eyeing the fragments in the tableau, and know with a profound assurance that I want to exist more than I ever have.

Anderson, Patrick. “Introduction.” So Much Wasted: Hunger, Performance, and the Morbidity of Resistance, Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822393290-001

———. “The Archive of Anorexia.” So Much Wasted: Hunger, Performance, and the Morbidity of Resistance, Duke University Press, 2010, pp. 30–56. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822393290-002

Caplan, Paula J., and Jo Watson. “Why Must People Pathologize Eating Problems?” Mad in America: Science, Psychiatry and Social Justice, February 15, 2020. https://www.madinamerica.com/2020/02/pathologize-eating-problems/

Cobb, Gemma. Negotiating Thinness Online: The Cultural Politics of Pro-anorexia. Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429491795

CooneyContent, “Eugenia Cooney flashes us.. again,” YouTube. January 21, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MQrZbQA6wJk

Cooney, Eugenia. @eugeniacooney. 2011–2023. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/eugeniacooney

———. @eugeniacooney. 2011–2023. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/eugeniacooney

———. “I’m Back.” YouTube. July 19, 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LIpDihSWPF0

Doyle, Glennon. Love Warrior. Flatiron Books, 2016.

———. Untamed. The Dial Press. 2020.

Fournier, Lauren. “Introduction: Autotheory as Feminist Practice: History, Theory, Art, Life.” Autotheory as Feminist Practice in Art, Writing, and Criticism, MIT Press, 2022, pp. 14–15. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13573.001.0001

Keeping Up With Eugenia. “Full video of Eugenia Cooney crying on TikTok live!! 2/9/2024.” YouTube. February 11, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fcgGFwgB4B8

Kephart, Beth. Handling the Truth: On the Writing of Memoir. Penguin, 2013.

Love Eugenia Cooney. “Eugenia Cooney (Before & After).” YouTube. December 18, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fhdAy1_cPd4

———. “Eugenia Cooney Crying Long Version (Cries 10 Minutes Into Video When Pressured On Jaclyn Glenn/5150).” YouTube. April 13, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uergm8MpWOs&t=648s

———. “Eugenia Cooney Emotional Over Always Being Harassed About Her Weight & Health Twitch July 15, 2021.” YouTube. July 16, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jDO1-GqFVh8&t=269s

———. “Eugenia Cooney's New Bikini (8–29–22).” YouTube. August 29, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vG09cgWpi08

———. “Eugenia Cooney Says She Will Not Die Anytime Soon Twitch July 23, 2021.” YouTube. July 24, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CY-JEoBFFgk

———. “Eugenia Cooney Shows Her Avril Lavigne Collection Plaid Crop Top & Skirt YouTube January 22, 2023.” YouTube. January 22, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1LamC8h-6xo

Muck Rack. “We Can Do Hard Things with Glennon Doyle.” https://muckrack.com/podcast/we-can-do-hard-things-with-glennon-doyle/

OnyxPink. “The Dark Descent of Eugenia Cooney.” YouTube. November 24, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j7o-sCB9qz8

Pinheiro, Andréa Poyastro, et al. “Sexual functioning in women with eating disorders.” The International Journal of Eating Disorders, vol. 43, no. 2, 2010, pp. 123–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20671

Rich, Emma. “Anorexic dis(connection): managing anorexia as an illness and an identity.” Sociology of Health and Illness, vol. 8, no. 3, 2006, pp. 284–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467–9566.2006.00493.x

Shah, Sonali. “‘Disabled People Are Sexual Citizens Too’: Supporting Sexual Identity, Well-being, and Safety for Disabled Young People.” Frontiers in Education, vol. 2, 2017. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2017.00046

Swarte, Puck. “There’s Nothing I Can Do”: Subcultural micro-celebrity, transgressive bodies and the discursive practices on YouTube. 2018. Utrecht University, MA thesis.