To the members of “COVID foodways” Project: Matilda Baraibar, Alfredo Blum, Mauricio Cheguhem, Laurie Beth Clark, Michael Peterson and Micaela Trimble, for their rich insights along this project. We acknowledge the contributions during the early research process from Lucía Alves, Alana Caraballo, Ignacio Fernández Muszwic, Carolina Gomez, José Ignacio Padilla, Ademir Peña, and data analysis by Lucía Gaucher, and the very constructive comments of editors and reviewers to this work. We thank the support from SARAS Institute during the Food and Sustainability cycle. We deeply acknowledge the time and good energy from all interviewees, in particular people from ollas (Olla Ciudad Vieja, El Nido, among others) and volunteers at Solidaridad.uy. This work was funded by CSEAM-Udelar through the project 2020-111: “Impacto de la emergencia sanitaria sobre la Ruta de los Alimentos en Uruguay”.

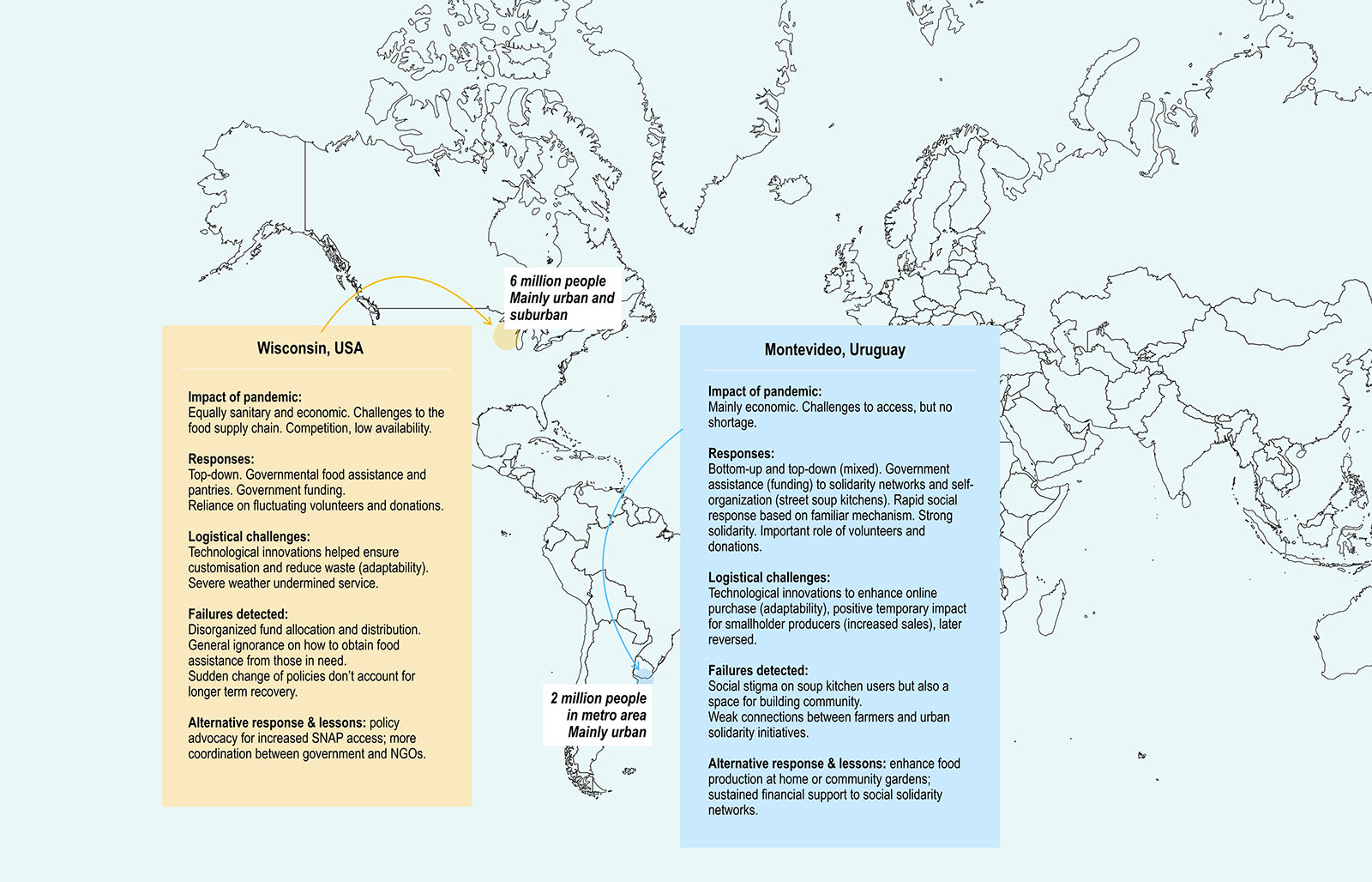

The COVID-19 pandemic has reflected our failures and successes as global society in responding to crises, particularly regarding food insecurity. Responses varied greatly around the world. Here, we aimed to identify and compare the government and civil society’s responses to food insecurity and hunger during the pandemic in Montevideo, Uruguay and Wisconsin, USA.

We analysed official data on hunger and hunger alleviation strategies and conducted a series of interviews with several Uruguayan and American stakeholders, from NGOs, grassroot organizations, and governmental officers, among other social actors. We also conducted online surveys addressed to Uruguayan consumers and farmers which were answered by over 750 people in the first months of the pandemic. Our analysis and narrative therefore builds on a mixture of qualitative and quantitative data. We enriched our analysis with a series of lived experiences that provided better insights into the feelings, actions and perceptions recorded in the interviews and surveys.

We highlight different response strategies (largely top-down in Wisconsin, and a mix of top-down and bottom-up in Montevideo), discuss some of their successes and failures, compare official and popular narratives, and reflect on potential changes to be made to help shape more resilient local food systems but also to enhance the resilience and dignity of communities facing hunger.

The COVID-19 pandemic is an unprecedented event in human history due to the huge and simultaneous disruptions on a global and local scale, transcending the direct impacts on people’s health. Case studies describing different impacts and response strategies are emerging in the literature, showing the deeply intertwined global functioning of systems of production and exchange of goods, including food, and the urgent need to change them (Béné; Klassen and Murphy; Sanderson Bellamy et al.).

Despite the global dimension of the pandemic, the experience of the crisis always happens on a local scale. Communities, rituals, lifestyles, and indeed bodies were shaken in multiple ways. Sets of strategies, norms, social practices, provisional solutions, and acts of care took many forms with different degrees of success in different parts of the world. As such, the sayings and doings constituted different performative experiences attempting to show and actively configure (Paavolainen) different everyday realities and ways to cope with change and uncertainty.

Recognizing that food insecurity and hunger are structural problems in almost all societies, here, we are interested in sharing and reflecting on the responses to the impacts of the pandemic on food insecurity of two different populations, giving voice to social actors who are usually marginalized. Learning from those local experiences may provide insights on how to reshape food systems to become more just, more resilient and sustainable, and to decrease the vulnerability of communities facing hunger beyond the pandemic (Ruben et al.).

In this work, we aimed to identify specific qualities that determine negative functioning of food systems, such as hunger or food insecurity, and qualities that can lead to hunger alleviation, in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Food security in emergency contexts (Pingali et al.) is one of the components of the resilience of food systems, in the understanding that food security is a fundamental outcome of food systems. In this conceptual framework, resilience and sustainability are complementary and mutually necessary, since sustainability is the dynamic capacity to keep providing food security for future generations, which is one of the characteristics of resilience (Béné; Tendall et al.).

To contribute to this broad aim, we focused on two case studies: Wisconsin (USA) and Montevideo (Uruguay), in which we identified government and civil society responses to food insecurity generated or exacerbated during the pandemic. Wisconsin is a midwestern state in the USA, with a population of almost 6 million people. Most of Wisconsin’s residents live in urban and suburban areas. Uruguay has a population of 3.5 million, mostly concentrated in urban centers (around 2 million between Montevideo and the metropolitan area).

The interdisciplinary nature of the present research triggered the utilization of eclectic methodologies. Our analysis is based on official data and interviews with various Uruguayan and American stakeholders, including consumers, food producers and farmers, NGOs, grassroots organizations, and government officials, mainly during 2020–2021. We deployed quantitative approaches such as virtual surveys conducted with food producers and consumers, with the aim of reaching a wide number of potentially very diverse people and therefore getting a more representative, although shallower, view than that obtained from the fewer in-depth interviews. Given the restrictions to face- to-face interactions, we designed, tested and conducted two semi-open surveys that circulated on social media between April and September 2020 in Uruguay. With the surveys, we were able to gather about 700 individual experiences from the public and about 60 experiences from food producers, during the period of the highest mobility restriction, highest social anxiety and uncertainty. In the case of the USA, virtual surveys were also circulated, but in contrast the responses were extremely limited and therefore not included in the quantitative analysis.

Such quantitative methods were combined with data obtained through qualitative methods such as in-depth interviews and participant observation during specific events, such as popular demonstrations coordinated by the network of Community Kitchens or food distribution instances, in the case of Uruguay. Additionally, in-depth interviews were conducted with organic farmers, artisanal fishermen, and NGO coordinators working on food recovery projects, which contributed to enriching the quality of the quantitatively obtained data by providing more depth to the information and bringing it closer to the lived experiences of researchers and the public. In particular, the interview conducted in the neighborhood organization “El Nido,” where interviewees shared their personal experiences of dealing with hunger, are eloquent examples of the potency of this type of approach.

Therefore, our work weaves together qualitative and quantitative data. The responses to our questionnaires and interviews with local social actors in both countries are intertwined with field observations and personal experiences of team members. The result does not intend to generate a single or complete story, but to stitch together different stories to offer new readings or openings to understand and learn from situated conditions in relation to food system features and failures.

In our work, we assume the concept of food security as encompassing four dimensions of food: availability (sufficient quantity and nutritional quality of food), accessibility (physically and economically), utilization potential (culturally, technically, and nutritionally appropriate for consumption), and stability in times of disturbance (FAO, “An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security”). Food security also includes nutritional security as a goal—not just calories but also quality nutrients (El Bilali et al.; Ingram). The lack of food security, on the other hand, can be understood and experienced in various degrees from mild to severe (FAO, “Hunger”)—which can give rise to the experience of hunger. This is an important consideration given that food insecurity and hunger is a ‘felt’, embodied experience that cannot be fully understood objectively or quantitatively.

The quantitative information helped us contextualize the impacts of the pandemic on food security on both locations, whereas the qualitative information helped us trace clear narrative threads through which to communicate the research findings. Having information obtained from experiential testimonies provides the depth we were looking for and helps to generate a strong identification of readers/viewers with the social phenomenon that we aim to account for. In this sense, some responses not only addressed the food insecurity of the less privileged citizens, but they could be understood as performative acts that created a community-based reality in the face of the isolation and confinement promoted by COVID-19. Such societal responses provided hope and emotional support besides a meal, creating pockets of reality that operated on a logic different from that proposed by the governmental mechanisms to address hunger. We expect our work to contribute to a reflection on how the pandemic-enhanced hunger was felt and how it was addressed, from individuals to organizations, highlighting contrasts in the specific tools used to alleviate hunger and in the narratives generated at those levels in the two different settings provided by the two case studies.

The effect of the pandemic in Wisconsin (USA), both on public health and food insecurity, was enormous. The latter was particularly noticeable by the increase in the use of NGO’s and on government food assistance benefits.

Feeding Wisconsin (a state association that works with Feeding America, a non-profit organization that coordinates a nationwide network of food banks) estimates that over 680,000 or almost 12% of Wisconsin residents (including 1 in 5 children) were food insecure in 2020 (Feeding Wisconsin). This is an increase from 2019, where around 530,000 Wisconsinites were reported as food insecure (Feeding America).

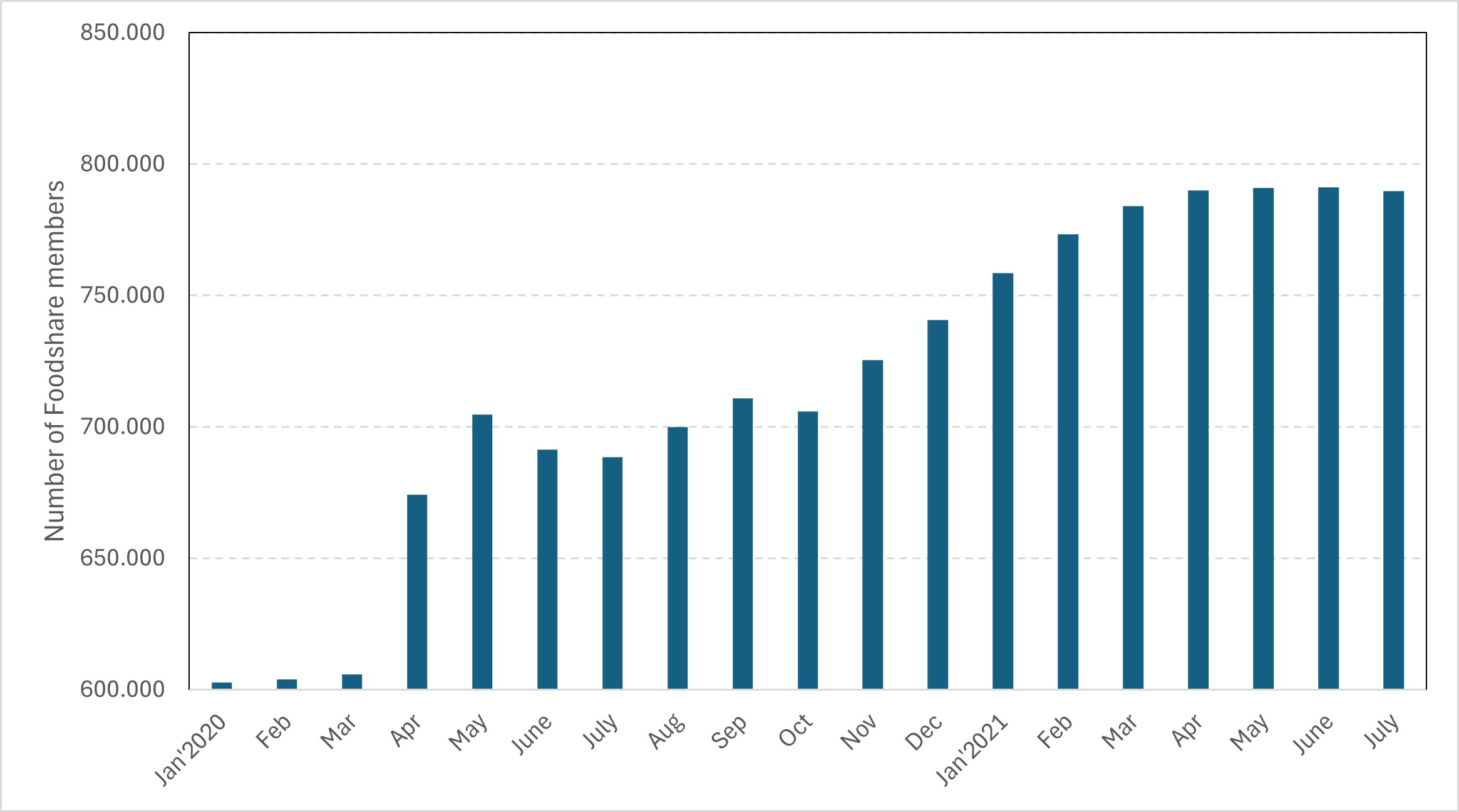

Some immediate responses from the government produced unrest in the population. The initial Wisconsin Supreme Court response was to overturn public health emergency declarations on March 31, 2020, which resulted in thousands of families losing their benefits. These sudden interruptions of benefits increased families’ uncertainty about how they were going to pay for food. However, different organizations such as Foodshare (a major national government program that distributes benefits or food stamps to eligible participants facing hunger and food insecurity) rapidly increased their responses. Official figures show that, as from April 2020, there was a sharp increase in the number of Foodshare members, first-time assistance groups,[1] and total issuance of Foodshare benefits. The number of Wisconsin participants receiving Foodshare benefits increased from about 600,000 members in March 2020 to almost 800,000 members in July 2021 (Wisconsin Department of Health Services) (Figure 1). The number of first-time assistance groups (AGs) more than doubled during the beginning of the pandemic, from ca. 4,000 in February to over 11,000 in April 2020. By July 2021, the numbers had substantially decreased, although were still larger than pre-pandemic figures.

Food insecurity was more common among people who lost their jobs and households with children, thus raising questions about equity and justice. In particular, people of color in the US had a much higher prevalence of food insecurity and a greater need to rely on formal and informal food support programs, compared to the non-Hispanic white population (USDA). Throughout each month of 2020, the majority of working families depending on Foodshare benefits consisted of one parent with minors. Importantly, many of these members were also people who had never experienced food insecurity prior to the pandemic.

As a result of the economic crisis, mobility restrictions, and increased demand for food generated by the pandemic, Feeding Wisconsin faced many operational changes in its usual management (S. Dorfman, interview conducted on July 23, 2021). The disruption of supply chains and the decrease in food donations made it difficult for staff to obtain canned fruits, meat, vegetables, and basic household foods. Retailers (e.g., warehouses) were usually the organization’s strongest partners, but the food shortage posed a challenge and created a competitive environment between the two parties, due to lower availability caused by failures in food distribution.

On the other hand, the growing health concerns of COVID-19 caused food drives to be put on halt. Some food banks closed volunteering opportunities altogether. Many volunteers over the age of 60 were no longer allowed to help due to their higher vulnerability to the virus. Feeding Wisconsin’s public outreach specialists could no longer go to pantries, community centers, libraries, or any public events to inform people about the benefits of Foodshare or support them through an application. As a result, people often did not know where and how to get food and the help they needed. This disruption in the system was evidenced during the interview with a key referent of one of this major organization.

Our food banks were also put in a tough situation where it was kind of the perfect storm of a situation where not only did we see this huge increase in demand, but we also, for a while, put a halt on food drives because we didn’t know if it would be safe to collect food in that way. (S. Dorfman, referent of Feeding Wisconsin, personal communication)

In this case, a support system and structure reliant on different forms of solidarity and acts of care by various individuals failed in the face of overlapping challenges and uncertainties—especially the potential risks to individual health. A more resilient scheme would require that these functions are not solely reliant on single sources or supported by volunteers motivated by their own moral values and fed by individual sacrifices.

Before the pandemic, people were able to choose what they wanted to eat and the pantries strived to meet their dietary, religious, and cultural preferences. This option was no longer possible during the pandemic since all of the food pantries were moved to outdoor distribution and only served pre-boxed household portions in order to ensure health safety (Figure 2).

Pre-packaged food boxes from food banks enabled volunteers and participants to practice social distancing; however, some of the participants felt dismayed in their lack of choice due to the prepackaged meals and food boxes. In turn, this led to an increase in food waste since many people received food items that they were unable to use due to dietary or cultural restrictions, or simply did not want.

The lack of food choice for participants and the shortage of volunteers highlights the need for greater investment in supplying the necessary materials and resources for staff and participants. Despite these limitations, different innovations emerged. Some adaptive and flexible responses by many food pantries included the mobile pantries, curbside pickups, and switch to online orders. This enabled people to fill out an online form in advance and indicate items they actually wanted for their packaged boxes. The image below (Figure 3) shows a pantry drive-thru in Wisconsin while visualizing the interactions and conditions of volunteers and benefit-recipients. Needless to say, such a solution was heavily reliant on the availability or accessibility of a vehicle, and on access to a cell phone to organize appointment pick-ups.

The advantage of virtual food banks was that they allowed people to choose the food they wanted, which reduced both health risks and food waste. Other pantries utilized public lockers, where people could pick up food from a refrigerated locker with a given code. This innovation enabled a safe and destigmatized form of accessing food aid without face-to-face contact. These innovations also reduced the amount of time (and health risk) that it usually takes to wait in long lines at food pantries or in crowded rooms.

On the other hand, the Emergency Food Assistance Program’s (TEFAP) Winter Distribution Survey in 2020 highlighted many logistical challenges that occurred during the winter months of the pandemic.[2] Weather related issues caused difficulties particularly for handicapped individuals. Another concern was protecting the food from snow and keeping volunteers warm enough while distributing food boxes outdoors. Food pantries organizers highlighted the need for more investment in tents, waterproof signs, electronic check-in services, and warm clothes for the volunteers.

In Uruguay, the impact of the pandemic was much greater at the socio-economic level than at the health level as compared with other countries’ numbers of casualties. It is estimated that around 100,000 more people fell below the poverty line in 2020 (from a total population of nearly 3.5 million). The emergency due to the pandemic implied severe restrictions to mobility, online working, and home schooling for a large proportion of the population, immediately affecting the means of living of many.

Several initiatives were developed by the central government in response to the immediate food crisis, supported by the extra funds gathered with the “Solidarity Fund COVID-19” that included central budget funds plus a fraction of the salaries of most civil servants. Such initiatives were mainly executed through the National Food Institute (INDA) of the Ministry of Social Development (MIDES). Early logistic problems were quickly solved, and schools were able to keep offering pre-packaged meals to children despite being shut down for months (M.R. Curutchet, INDA, personal communication, March 2021). In the early months of the health emergency, the government announced plans to support school feeding, delivery of food baskets, food vouchers,[3] and support to popular soup kitchens, locally called “ollas populares” (name that we use hereafter to differentiate them from other soup kitchens organized by government agencies or given to third parties). Several of these statal supports required demonstrating certain socio-economic conditions to apply. According to MIDES, more than 1 million food baskets had been delivered since the beginning of the pandemic by the end of 2020, and 310,000 (roughly 9% of the national population) people received them in early December 2020.

At the level of departmental government (municipalities), there were also various programs to address emergent hunger. In Montevideo, the ABC Plan of the municipal government supplied food, cooking elements and hygiene items (M. Rodríguez, Montevideo Municipality, personal communication, June 2021) to the network of ollas populares in Montevideo (organized in the Popular and Solidarity Coordination, hereafter CPS).

Showing the highly political nature of responses to hunger, solidarity initiatives closely linked to private enterprises and to the business world (such as Unidos para Ayudar [“Together to Help”] or Uruguay Adelante [“Go Ahead Uruguay”]) received the support from government officials and favorable opinions from the mainstream media and press (e.g. Uruguay Presidencia).

A narrative was constructed in which initiatives of this kind, originating from high-public profile individuals and newly created organizations, were portrayed as apolitical or free from political interests, and therefore, more desirable or supportable by certain sectors of society than the popular initiatives described below.

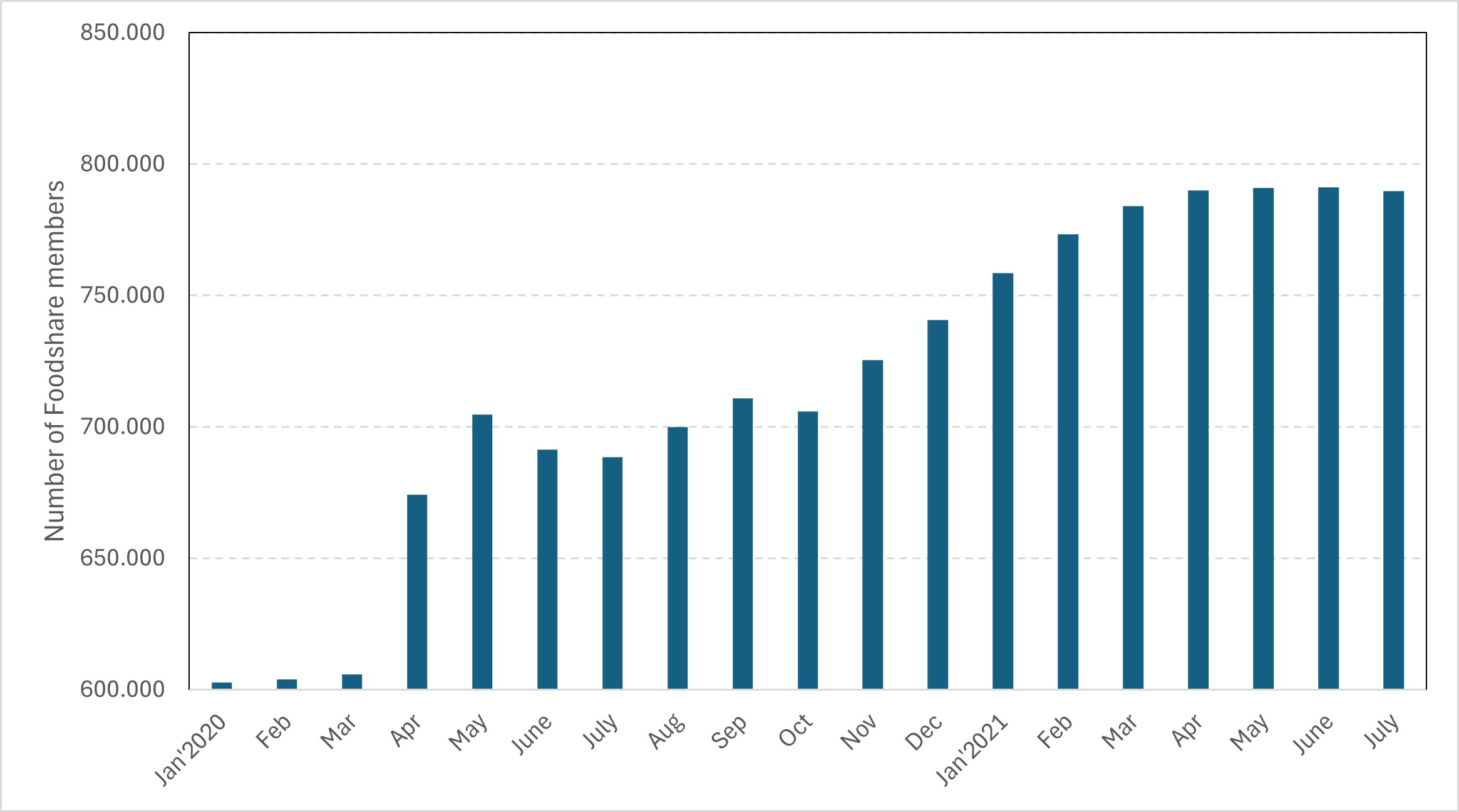

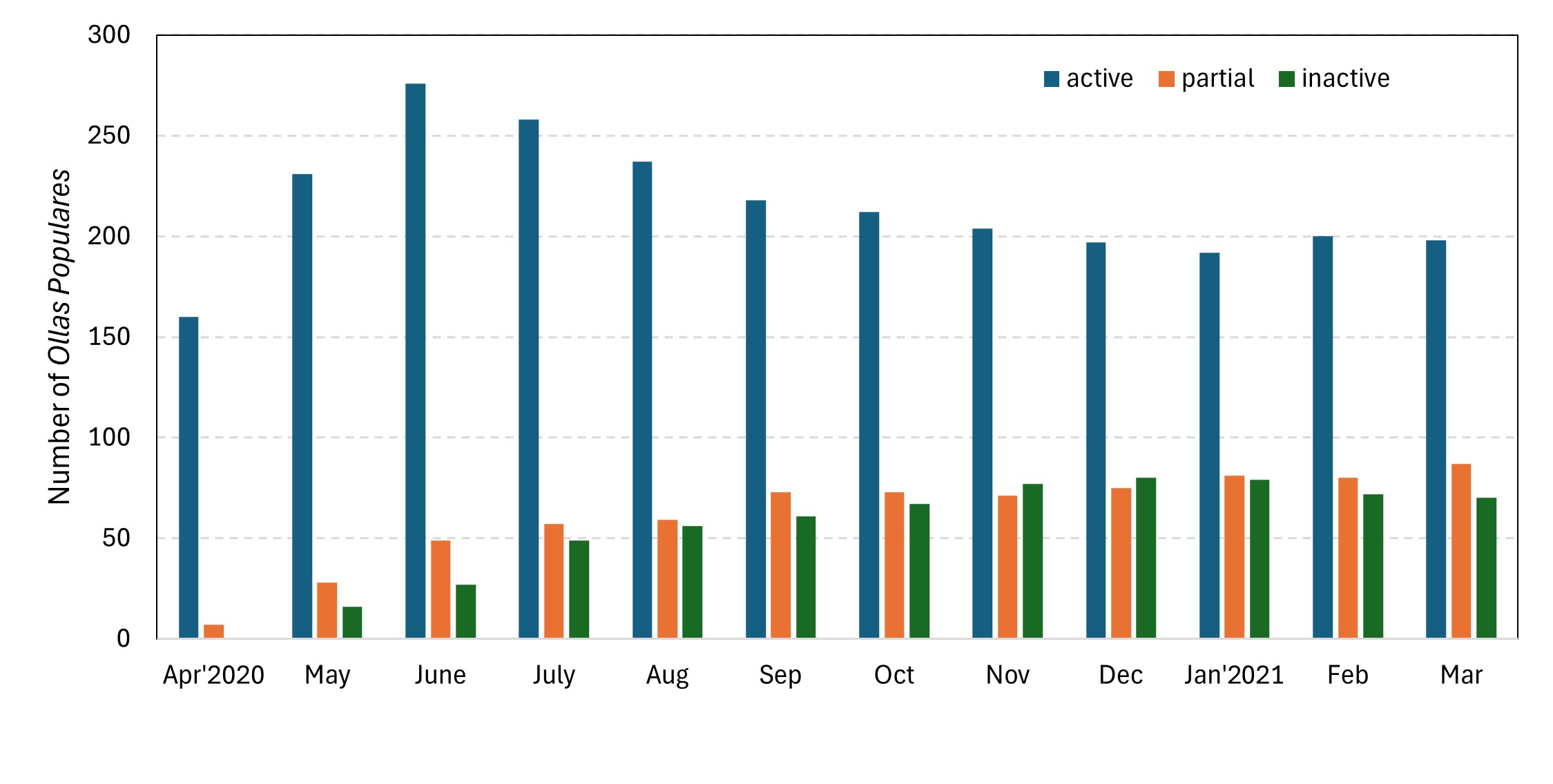

At the civil society level, however, the most notable responses were the more than 700 grass root initiatives between ollas populares (hereafter ollas) and merenderos that emerged at the beginning of the pandemic (Rieiro et al.).[4] Ollas are organized and managed by hundreds of volunteers who rely on donations of food and essential items to prepare meals for thousands of people. Most of the volunteers and donors were neighbors (Figure 3), followed by union workers, anonymous citizens, and students.

It is estimated that over 60,500 hours of (unpaid) volunteer work were performed at the ollas per week (Solidaridad.Uy). April and May 2020 were the months with the highest number of people feeding themselves from ollas, with over 800,000 plates of food served per month in Montevideo alone (Rieiro et al.). For instance, in March 2020, the Olla Ciudad Vieja (“Old City Pot”) was started by a group of residents of the neighborhood that saw the increasing hunger toll the pandemic was having on families, people living in the streets, and migrants (C. Sarasola, Olla Ciudad Vieja, personal communication, June 2021). Due to the good public transport connections, this olla received people from distant neighborhoods where there was no local food assistance.

As the weeks passed, articulations between ollas began to emerge, with the creation of the Red de Ollas Populares (“Soup Kitchens Network”), to achieve coordination among the 229 ollas existing in Montevideo at that time. Solidaridad Uruguay was another social initiative that emerged immediately (March 2020), originally formed by students, faculty, and graduates from the School of Engineering at the Universidad de la República (the only public and free university in the country), with the aim to voluntarily provide technical support to strengthen coordination among solidarity networks. This initiative later gathered more volunteers from different backgrounds and expertise.

In other parts of the country, several soup kitchens did not respond to grass root movements or self-organized people but rather were organized by municipal governments. In these cases, hot meals were provided in large open barracks, or outdoors and sometimes on the street, often using soldiers of the national army to cook and/or serve the portions. Several users of these government initiatives highlighted the stigmatization and shame resulting from the act of standing in line, in full view of the members of their communities, to receive the handout, typically a pre-packaged tray or a plate of hot food. Accounts from the use of the different ollas offer further nuance on the contrasting emotional experiences they represented.

During the interview, Amalia emphasized the differences between the olla organized by the collective El Nido (“The Nest”), and the soup kitchen provided by soldiers alongside the Municipality of the city of Maldonado. While the former focused on an approach centered on human dignity and comprehensive subject support (e.g., games and cultural activities were offered around food distribution, generating the feeling of going together through the tragedy of hunger), the latter focused on control and a supposedly rational use of resources, expressed in phrases like “they (the users) should be grateful because they are given a plate of food.”:

Here [at the olla popular], everything was dealt with a social level that supported you and made you rise up: “C’mon, we can do it.” And there [at the municipal soup kitchen], they treated you like: “Be grateful we’re giving you a plate of food,” “How dare you complain about the food!”, “They complain about the food, these people actually have more than enough, they come just for fun.” They’ve said things like, for example, “This isn’t a restaurant.” (Amalia, user of both an olla popular and a municipal soup kitchen, August 2021)

In this sense, the experience of eating and how hunger was felt or perceived was lived in radically different ways. Ollas populares offered social support embodying conviviality and communal acts of care. There, neighbors would cook and share the meal together as peers, regardless of whether they actually needed that meal or not. According to the organizers of the Red de Ollas Populares, most ollas received very little government funding from the start, raising criticisms and complaints. These criticisms continued throughout 2021 and 2022, when tensions between organized civil society groups and the government became more virulent. This tension was and continued to be (as of March 2024) explicitly shown with demands from governmental officials for ollas organizers to release users’ data, threatening to cut their support in case of refusal. This led users and volunteers to organize street demonstrations held under slogans such as “Enough is enough’”, “Absent state, solidarity present “, “If there is hunger, there is fight”, in August 2021 and October 2022 (Figure 4).

These responses were evidence of the mixed reactions and feelings that the very existence of ollas triggered among the volunteers. Some would see ollas as an opportunity to build links and as a ground to exercise solidarity, a place of communion among neighbors and fellow citizens. As one of the referents puts it below, a place to foster empowerment and agency:

We would like that users of ollas empower themselves and consider ollas as their own thing. We would like them to feel part of it and take responsibility for some tasks. Because this is not a charity activity; this is solidarity. There is a huge difference. (Referent from Olla Popular Ciudad Vieja, August 2021, who preferred to remain anonymous)

This vision, as shown earlier, contrasts with that of state agencies or the private sector that worked from a perspective of social assistance in the face of the emergency, but far from generating social organization around the issue of access to food or eventually advancing towards a model of food sovereignty. In contrast, the official or officially- promoted initiatives promoted social demobilization, hopelessness and stigmatization.

Other volunteers would see ollas as a sign of societal failure, exposing the fragility of members of their community that were not perceived by others or by themselves as subjects of assistance until the pandemic. During the interview conducted with members of El Nido organization, one of them reflected on the fragility of a food system sustained by the logic of capital, where a disruption in the flow of income in a family compromises their food security.

It was very shocking to see the conditions in which many neighbors found themselves, who were not necessarily people with low resources; but rather the pandemic had hit brutally there, on the worker. (Lucía, volunteer in the neighborhood olla El Nido, August 2021)

Some of the interviewees also elaborated on the lack of a holistic approach from the state to assist socially vulnerable people. Their concerns extended beyond the responses to alleviate hunger, but also covered emotional aspects and impacts on mental health, employment, and caregiving tasks that were hit by the pandemic and the restrictions that followed.

Volunteers of ollas highlighted the fact that the duration of the pandemic effects allowed them to reflect critically on the situation and context and to do so collectively, reaching conclusions or insights that would not have been identified had the pandemic been shorter. Many would express their frustration with anger and deep political reflections.

The first thing I have to say about this, as a collective, is that we are convinced that ollas should not exist. At least not as they are now. Nutrition is a right, and people should be able to eat at home, choose what to eat, pay for what they want to eat, and have it in their own home. From that point of view, we start with the premise that there is a right, which is the right to nutrition, that is not being covered, that the state is not taking care of, and that this government is not taking responsibility for. (Referent from Olla Popular Ciudad Vieja, August 2021)

With the loosening of mobility restrictions and a return to semi-normal conditions for much of the population by 2021, many ollas closed due to a lack of donated food and volunteer resources, despite the fact that the need for food assistance continued to be high (Solidaridad.Uy, 2022) (Figure 5).

In stark contrast to the situation of the several thousands of people that experienced hunger either before or due to the pandemic, our online surveys allowed us to get to know the situation of people largely living in less vulnerable conditions. We could access opinions from the general public in a massive way (around 700 responses). Closed and semi-open questions allowed participants to express their feelings in the most uncertain moments of the pandemic. The respondents were a majority of women, living in cities, with at least secondary education completed. Most respondents had the economic and emotional resources and time to participate in the survey. For this part of the population, typically wage-earners, middle-class and urban, the pandemic meant an opportunity to reflect on their own nutrition, food practices and well-being. Most of them reported having had more time to eat, cook, and focus on healthy eating. Spending more time at home provided the right setting for many to try changes in cooking and eating habits, explore new recipes, and prioritize homemade food and nearby shopping in small groceries, street markets and open fairs, with expected lower risk of getting infected by the virus. These changes in feelings and behavior are shown by some of the self-reflection examples provided below:

Except for eating more often due to anxiety, I did not change my diet much. I am privileged (as my income did not change), and able to explore new recipes in the kitchen. (Laura, 25 years old, postgraduate student, online survey April 2020)

For most of these respondents, as Alejandro’s account confirms below, the pandemic was therefore seen as more an opportunity than a risk when it came to its impacts on their nutrition and relation to food.

I believe the pandemic is an opportunity to modify certain feeding habits, and once changed, it will be easier to continue with a healthier diet. (Alejandro, 48 years old, civil servant, online survey May 2020)

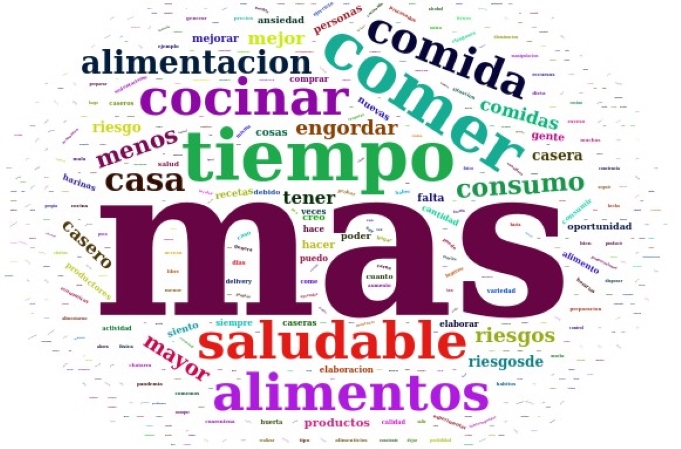

In addition, a revision of the language and most frequent terms adopted in responses (Figure 6) confirmed the relatively positive views and the low frequency of terms associated with risk or overall negative perceptions. Risk-related concepts were less frequently mentioned than positive or opportunity-related concepts, contrasting the situation of hunger faced by thousands of fellow citizens described before.

On the other hand, testimonies like the one from Santiago (who abruptly lost his daily wage with the decreed closure of construction activities and thereafter partly depended on solidarity initiatives), attest to the embodied nature of a sudden and insightful experience of hunger:

The pandemic gave me the opportunity to get to know myself better, and the opportunity to learn what it means to be hungry. (Santiago, 38 years old, construction worker, online survey May 2020)

These experiences also confirmed the pandemic’s impact on the reconfiguration of social relations, at times flattening or blurring previous seeming boundaries or differences between social classes or affiliation groups. For example, some respondents reflected on the pandemic as an opportunity to develop new ways of interacting with fellow citizens and neighbors in a horizontal way.

I believe [the pandemic] stimulates food sovereignty with the creation and use of home gardens, for instance, and promotes the exchange among neighbors and certain groups. (Tania, 20 years old, student, online survey May 2020)

Survey results highlighted that many people used their time at home to create small green spaces and cultivate small crops. For many, this was seen as a pleasant and therapeutic experience, but for many others, it represented a significant strategy to cope with food insecurity and compensate for income losses. Indeed, several initiatives involved the emergence or expansion of community gardens for the production and self-consumption of fresh food, based on seeds provided by government agencies or in exchange fairs and street markets. Many of these community gardens self-organized to create the Network of Community Gardens of Uruguay. Some are still active (as of April 2024) and use social networks to continue to organize gatherings. Ironically, the agreement between the School of Agronomy from Universidad de la República and the National Administration of Public Education (ANEP) to provide technical support to the primary schools’ gardens program was canceled by the new authorities of ANEP in 2020 while the pandemic was at its highest peak of uncertainty (B. Bellenda, School of Agronomy, personal communication, March 2021).

An important consideration is that both ollas populares and community gardens were initiated by social activists and grass roots organizations. In this case, the main innovations perceived relate more to new ways of self-organization and collaboration-especially the development and support of networked action.

In this sense, the idea of nurturing—and not just providing a meal—explains the overarching purpose of these groups. This applies from the literal to the metaphorical, as expressed by one of the referents of the already described social organization El Nido:

It’s nourishment we need, not just food. And nourishment is the food that we are going to sow in the ground, that will nourish us as a collective. (Donovan, referent from collective El Nido)

This idea represents reflections regarding the connection between nature and social practices such as those around the table and highlights the interdependence between food sovereignty and food security. At present (as April 2024), however, as was the case with the number of volunteers working in the ollas, the number of people involved in the community gardens decreased as the economy recovered and people had less free time.

Besides the experiences lived by consumers, we were interested in the effects of the pandemic on food producers, being farmers or other types such as artisanal fishermen, and on the potential impacts on the connections between food producers and consumers. For this analysis, we used survey quantitative data together with qualitative data from open interviews to key referents of government agencies and social organizations. According to our survey addressed to food producers, about one third of farmers of small and large scales experienced some negative effects during the first months of the pandemic. Food production as such was not affected. However, small-scale organic farmers saw a strong increase in their sales at that time, particularly those that made a rapid switch to online sales (e.g., using social media and WhatsApp) or who offered home delivery of produce baskets. As seen in the Wisconsin food pantries, technological innovations offered new windows of opportunity. However, once mobility restrictions were lifted and the sense of health risks declined, organic farming sales returned to pre-pandemic levels (F. Bizzozzero, CEUTA, personal communication, March 2021).

The weak or non-formalized connections between local farmers’ associations and ollas complicated the access of users to varied, fresh and healthier products other than the few, long-lasting and easy-to-store vegetable items or canned foods typically used in pot meals. However, some initiatives to improve such links were attempted. The National Food Institute of Uruguay (INDA) started to buy fresh produce from nearby small-scale farmers to provide public kindergartens in several locations in the country, but state bureaucracy, among other factors, hindered the reach of these initiatives (M.R. Curutchet, INDA, personal communication, March 2021). The Agroecology Network and Slow Food Uruguay movement launched public campaigns in which regular consumers could contribute with donations of organic produce to the ollas populares. This campaign was relatively successful but hard to sustain in time and was canceled after a few months.

A weak support from the State in funding, subsidizing, and in facilitating distribution networks and storage capacity, or the rigidity of some governmental tools and mechanisms, was highlighted as a serious limitation for this and other initiatives that aimed to simultaneously benefit several sectors of the population that were affected by the pandemic (L. Rosano, Slow Food Uruguay, personal communication, March 2021).

Food insecurity is a structural phenomenon in societies and a major failure of the prevalent capitalist and industrially based food system models. However, the disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led many people to face hunger for the first time and to have to resort to and depend on state food assistance programs, NGOs and/or on collective initiatives, to obtain immediate and direct help to feed their families. The two cases reported here showed sudden increases in the number of people accessing food banks in Wisconsin and to state assistance and soup kitchens or other safety net programs typically driven by organized civil society in Uruguay. The constellation of innovations, acts of care and solidarity, or governmental responses offer some insights into different stories of hunger and resilience, and the lessons that could be drawn to inform food systems change.

The pandemic exacerbated systemic food insecurity and hunger by largely affecting food access worldwide (Béné et al.). Pandemic had disproportionate impacts depending on social positions in both countries—socio-economic class, form of participation in labor market, ethnicity and gender. Our comparative study, based on official data plus qualitative and quantitative data generated for this research, revealed the vulnerability of food systems in both the United States and Uruguay. Many initiatives reviewed here relied on the unpaid labor by thousands of volunteers, which thrived under the exceptional conditions of the pandemic. However, the shortage of volunteers was common for contrasting reasons. In Wisconsin, the high risks to safety and health were decisive for the number of volunteers given their age class. In Uruguay, such decline in volunteer numbers in ollas populares was instead associated with people massively returning to the labor market when mobility restrictions ceased, as well as with volunteer burnout. It is worth noting that most volunteers were and still are women (Rieiro et al.; P. Pereira, APEX program, personal communication, March 2021), with comparatively low mean income and a heavy caretaking load at home. While these acts of care and philanthropy deserve a place without being commoditized, the competitive and transactional logic of the capitalist systems that underpin most people’s lives mean that caring rests on people’s free time and individual sacrifice.

It is interesting to highlight the differences between the performative quality of ollas populares, where there is no intention to emphasize the gesture of help but rather to focus on the quality of life of the residents; and on the other hand, the government’s and some private sector campaigns’ performative intentions, where the gesture of help was explicitly shown and publicly advertised and in itself constituted a purposeful performative exercise (Paavolainen). Recipients of such food assistance become or are expected to become, in that logic, grateful objects of charity. The same overall consideration of the performative quality of Uruguayan top-down strategies would apply to the food delivery system that took place in Wisconsin. In contrast, while government proposals emphasized providing short-term food solutions, ollas populares also often added educational support and recreation spaces for children from the neighborhoods where they operated, and in some cases, food production projects through community gardens. The collective management of ollas populares can be understood as a deeply performative action not initially designed as such, which, in addition to addressing food access, transforms reality by creating emotionally safe spaces for neighbors and other users. Participants of ollas become, therefore, rights-holders and active members of a horizontal, solidarity network.

The pandemic also revealed failures of all governments in their capacity to respond and adapt to a complex and unprecedented crisis. Political distrust between the government and popular solidarity initiatives jeopardizes the persistence of several such initiatives in Uruguay. In the USA, most institutions and programs received government funding, but disorganization in the allocation and real need of resources caused logistical failures as seen in Wisconsin. As stated elsewhere, in times of crisis, urgency might override other concerns, and thus decision-making may further entrench injustice (Sanderson Bellamy et al.).

The experiences illustrate many failures but also show some resilient characteristics (Figure 7). New positions, understandings and relationships were built in response to the shocks. In the case of Wisconsin, innovations to overcome the challenges imposed by the pandemic were mostly technological and demonstrated flexibility and adaptation, characteristics that can contribute to the resilience of food systems (in the sense of resilience as developed in Tendall et al.). For instance, virtual options helped increase peoples’ access to and awareness of food assistance, along with providing them choices that aligned more with their dietary preferences and basic needs. The creative adaptations of the food banks proved effective particularly in helping people experiencing food insecurity for the first time, with the side effect of reducing the feelings of shame or stigma of food insecurity.

In Uruguay, some of the innovations were prominently focused on supporting self-organization and structuring which relied on the developing and strengthening of existing networks and links within and among different components of the food system. Networked and coordinated actions and collaboration resulted in better outcomes. Besides more investment and a stronger support from governmental institutions, such coordination could be stronger and more fluid, for instance, between the many small- scale farmers that mostly concentrate in the rural areas of Montevideo County and those in need of food assistance, such as the organization of ollas populares that proliferated in the capital city and also elsewhere in the country.

This overview of learnings could contribute to rethinking aspects of the food systems in both our cases and likely elsewhere. More resilient systems would imply promoting different routes and mechanisms of production, distribution, and access to food, especially fresh and healthy food, leading to greater redundancy and overall flexibility in the system (Tendall et al.). Having significant resources of different sorts, governments could develop stronger policies and long-lasting strategies to support small-scale farmers and local food retailers, for example by ensuring the purchase of their production to supply elementary schools, soup kitchens, and state food banks. To facilitate this link, training for farmers and food retailers to help them navigate through the state bureaucracy might be needed. These measures would have the dual effect of protecting typically weak food producers and sellers by securing the sale of their products at a fair price while simultaneously providing fresh and high-quality food to socially vulnerable, often under and malnourished, populations. Food waste could also be reduced as a consequence.

A challenge remains to consolidate such emergent links and innovations in the long term once the pandemic and its effects have ceased, as other food crises can be anticipated acting on top of structural hunger. In the future, negative results must be prevented by taking more holistic or systemic views of food including the interactions between production, exchange, consumption, and waste, but also, including adjacent systems (such as health, energy, and education).

Emergent and structural hunger show that food security is at odds with free market logic, as the actual access to food results from the consumption capacity of people rather than from the respect of a human right and the pursuit of justice. Most governmental actions in the pandemic seemed to assume that food insecurity was a problem that people could quickly recover from, without considering the complexity of the problem and the chronic and lasting effects of socio-economic difficulties (such as increased unemployment and job insecurity and loss of social resources and safety networks), which are not reversed by lifting distancing measures or declaring the end of the pandemic (as discussed elsewhere, e.g. Ranta and Mulrooney).

The fact that resolving crisis situations largely depends on social devices by the civilian population is both questioning and hopeful. Faced with disaster, many people choose to save themselves collectively. Both food banks and ollas populares are examples of this and perform the social action of prefiguring the material, affective and cognitive reality shaping meanings and purposes in the face of uncertainty and unmet needs. People’s solidarity remains in many acts of care even after the pandemic emergency ceased, but support structures to ensure the right to nutrition and food security cannot and should not rely on solidarity alone, rather a strong support and interventions from the State are required.

A mutual reinforcement of bottom-up and top-down approaches, generating a diverse, flexible, and robust strategy that places the protection of life and human dignity at the center is needed. The individual and collective experiences shared here highlight the need for a stronger involvement and commitment from governments in alliance with civil society to nourish families and whole communities. This ability for self-determination, empowerment and care, seems a clear way in which communities can become resilient to present and future crises.

However, unless food security can be ensured, food systems will remain unresilient and unsustainable. The pandemic provoked deep reflections on people’s relationship to food and hunger in particular, and it enhanced empathy and the urgency for organized action, and even promoted small changes in social practices (e.g., community gardens). As several aspects of life have returned to pre-pandemic levels and models, however, the persistence, depth and breadth of these learnings is yet to be seen.

[1] AGs are Foodshare eligible individuals who live in the same household and purchase food together.

[2] The Emergency Food Assistance Program (TEFAP) is one of the smaller federal programs that provides emergency food assistance to low-income Americans.

[3] Food vouchers: people can exchange these tickets for food in most groceries and supermarkets; baskets often are boxes or bags with basic—mostly dry—food supplies.

[4] “Ollas Populares” represent a self-organized social device activated during different crises in Uruguay (Rieiro et al.). “Merenderos” are closed places where food is served, mostly to children, typically breakfast or an afterschool meal (milk and some minor plates) but sometimes also lunch. Several ollas and merenderos sustain the daily feeding of vulnerable populations outside of extraordinary crisis contexts.

Béné, Christophe. “Resilience of Local Food Systems and Links to Food Security - A Review of Some Important Concepts in the Context of COVID-19 and Other Shocks.” Food Security, vol. 12, no. 4, 2020, pp. 805–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1

Béné, Christophe, Deborah Bakker, Mónica Juliana Chavarro, Brice Even, Jenny Melo, and Anne Sonneveld. “Global Assessment of the Impacts of COVID-19 on Food Security.” Global Food Security, no. 31, 2021, 100575. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2021.100575

El Bilali, Hamid, Carolin Callenius, Carola Strassner, and Lorenz Probst. “Food and Nutrition Security and Sustainability Transitions in Food Systems.” Food and Energy Security, vol. 8, no. 2, 2019, e00154. https://doi.org/10.1002/fes3.154

FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). “Hunger.” Accessed March 30, 2023. http://www.fao.org/hunger/en/

———. “An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security.” 2008. https://www.fao.org/agrifood-economics/publications/detail/en/c/122386/.

Feeding America. “Map the Meal Gap.” 2021. https://map.feedingamerica.org/

Feeding Wisconsin. “Feeding Wisconsin COVID-19 Network Response.” 2021. https://www.feedingwi.org/programs/covid-19/.

Ingram, John. “Nutrition Security Is More than Food Security.” Nature Food, vol. 1, no. 1, 2020, p. 2. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43016-019-0002-4

Klassen, Susanna, and Sophia Murphy. “Equity as Both a Means and an End: Lessons for Resilient Food Systems from COVID-19.” World Development, vol. 136, 2020, 105104. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105104

Paavolainen, Teemu. “On the ‘Doing’ of ‘Something’: A Theoretical Defence of ‘Performative Protest.’” Performance Research, vol. 27, no. 3–4, 2022, pp. 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2022.2155394

Pingali, Prabhu, Luca Alinovi, and Jacky Sutton. “Food Security in Complex Emergencies: Enhancing Food System Resilience.” Disasters, vol. 29, 2005, pp. S5-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0361-3666.2005.00282.x

Ranta, Ronald, and Hilda Mulrooney. “Pandemics, Food (In)security, and Leaving the EU: What Does the Covid-19 Pandemic Tell Us about Food Insecurity and Brexit.” Social Sciences & Humanities Open, vol. 3, no. 1, 2021, 100125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100125

Rieiro, Anabel, Diego Castro, Daniel Pena, Rocío Veas, and Camilo Zino. “Entramados comunitarios y solidarios para sostener la vida frente a la pandemia - Ollas y merenderos populares en Uruguay 2020” (“Community and solidarity networks to sustain life in the face of the pandemic - popular kitchens and soup kitchens in Uruguay 2020”). 2021. Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Udelar, Uruguay. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12008/34243

Ruben, Ruerd, Romina Cavatassi, Leslie Lipper, Eric Smaling, and Paul Winters. “Towards Food Systems Transformation—Five Paradigm Shifts for Healthy, Inclusive and Sustainable Food Systems.” Food Security, vol. 13, no. 6, 2021, pp. 1423–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-021-01221-4

Sanderson Bellamy, Angelina, Ella Furness, Poppy Nicol, Hannah Pitt, and Alice Taherzadeh. “Shaping More Resilient and Just Food Systems: Lessons from the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Ambio, vol. 50, no. 4, 2021, pp. 782–93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13280-021-01532-y

Solidaridad.Uy (2022). Situación de ollas y merenderos populares en Uruguay: Informe anuel 2021–2022 (“Situation of popular soup kitchens and eating places in Uruguay: Annual Report 2021–2022”). 2022. https://www.solidaridad.uy/_files/ugd/df0bed_6ad0d2d51c6d4bb5a467ee2faa507927.pdf

TEFAP (The Emergency Food Assistance Program). “Winter Food Distribution Survey 2020.” 2021. https://www.feedingwi.org/content/TEFAP%20Winter%20Food%20Distribution%20Survey%20Results%202020.pdf

Tendall, Danielle, Jonas Joerin, Birgit Kopainsky, Peter Edwards, Aimee Shreck, Quang Bao Le, Pius Kruetli, Michelle Grant, and Johan Six. “Food System Resilience: Defining the Concept.” Global Food Security, no. 6, 2015, pp. 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2015.08.001

Uruguay Presidencia. “Unidos para Ayudar prevé entregar 150.000 canastas alimenticias para personas en situación de vulnerabilidad.” June 22, 2021. https://www.gub.uy/presidencia/comunicacion/noticias/unidos-para-ayudar-preve-entregar-150000-canastas-alimenticias-para-personas.

USDA (US Department of Agriculture). “The Emergency Food Assistance Program.” https://www.fns.usda.gov/tefap/emergency-food-assistance-program.

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. “FoodShare Wisconsin at a Glance.” https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/foodshare/fsataglance.htm