In 2022, Dr. Jazmin Badong Llana invited the art collaborative Spatula&Barcode to the Philippines to create Foodways Philippines, a project about the culture of hunger and hunger action. Llana’s invitation was part of a larger initiative on hunger, prompted by De La Salle University (where Llana is a Professor) that included the hosting of the 2022 Performance Studies international conference, also on the theme of hunger.

The challenge for all involved was to find an entry point for the arts and humanities into a sphere that is ordinarily the purview of social and biological scientists, religious and other charities, NGOs, and government bodies. The common understanding of how hunger is addressed centers policymaking and program funding at a huge scale, and the work of those directly engaged with hunger can seem engulfed by macro forces of biopolitics and bioscience.

What then can the arts and humanities do in the context of hunger and hunger action? This essay reflects on our process as we sought a few small answers to this question. We provide no grand theory, but we share some of what we learned through months of planning, six months in residence in Manila and around the country, and now more than a year of reflection and outgrowths of this project.

In Whose Hunger? Concepts of Famine, Practices of Aid, Jenny Edkins argues that hunger is structurally integral to modernity and cannot be solved by it, challenging the ways that hunger and hunger relief have been conventionally understood. We believe that because hunger is not a natural but a social and historical fact, that we should understand hunger as a failure of imagination (about how society could be shaped)—and so then art must have a role in devising creative and resilient strategies.

As the following brief background on our practice will show, we share with many contemporary artists an expansive understanding of what art can be. Our work “makes sense” to us when considered under the rubric of “art/life”, “new genre public art”, or “social practice.”[1] We consider our work on the PSi conference (which included our own presentation, moderation and interlocution, helping with logistics, supporting Jazmin, and hosting online conference “receptions”) as well as our work on these two journals to be part of the larger Foodways Philippines project; however, this essay focuses specifically on our social practice artmaking in collaboration with Jazmin Llana[2] alongside various ongoing Filipino hunger actions, and seeks to place it in the context of broader questions of hunger and creativity.[3] This essay is structured as follows: background on Spatula&Barcode including our Foodways Projects, earlier connections with the theme of hunger, followed by brief accounts of some exploratory work with several groups in the Philippines and then a longer discussion of our larger collaborations. We conclude with some theoretical reflections on agency, sovereignty, and hospitality and a coda on a very simple answer to the question “What can art do?”

Spatula&Barcode is a US-based social practice arts collaborative founded by Laurie Beth Clark and Michael Peterson in 2008.

Originally conceived as an occasional and lighthearted relief valve to our work on emotionally fraught scholarly projects involving trauma and cruelty, Spatula&Barcode soon became the central vehicle for our artistic and even scholarly output. Our touchstone values are conviviality, commensality, and criticality. Our projects ask participants to collectively solve puzzles in conviviality—how can we be together, now, in this context? Within this shared endeavor, we promote critical engagement with issues specific to the project, from climate change to globalization to the meaning and making of place. Commensality—eating together—has been a central mechanism since our first project was realized in Zagreb in 2009; sharing food has utility for the way it can often instantly transform social relations into something else. These three terms are not without complications; indeed, there has been an extensive discussion in social practice art about, for example, when conviviality can be too easy or smooth over conflict, or how “much” criticality a social experience should entail. We work from a conviction that criticality and conviviality are not opposing terms, but that conviving is itself a critical practice and a means of knowledge production.[4]

In the last fifteen years, we have produced projects on six continents in a wide range of modes, from site-specific walking encounters to museum-based public interactions to immersive experiences for small groups of participants, but one aspect of our history is especially pertinent here. We gradually found that we had a penchant for collaborating not just with other artists and with the public, but with institutions themselves, including a strand of work that intervenes in academic conferences. For example, we went from “presenting” a “performance” at Performance Studies international 19 in Zagreb (Misadventure, 2009) to collaborating with the organizers of a small followup conference to engage all the attendees in a multi-site experience of place (Wish You Were Here, Rijeka, Croatia 2010).

In short, amongst all our ways of working, we came to understand that institutional collaborations at a range of scales was of particular interest, and our project in the Philippines indeed involved fitting ourselves alongside a range of institutional actors doing hunger work.

A second important context for the work in the Philippines is our shift from food as a method to food as a subject of inquiry. In 2015, we began our Foodways series. “Foodways” for us means how we “do food;” its anthropological meaning carries a sense of foods and food practices transmitted through culture.[5] Each project focused on a different theme in the broadest possible consideration of food culture. Foodways Darmstadt (Germany 2015) considered the mobility of food. Foodways Melbourne (Australia, 2016) centered on descriptive language of the food experience. Foodways Madison (United States, 2016) was about food systems. A planned Foodways Uruguay project in 2022 on sustainability branched into the online project COVID Foodways. Subsequent to our time in the Philippines, we were able to complete the cycle in 2023 with a series of Foodways projects on Migration in two locations in Africa (Accra, Ghana and Johannesburg, South Africa) as well as an epilogue that returned us to our starting point in Darmstadt.

A last, more oblique influence on our work in the Philippines was our shared understanding of how acute or “fast” violence is imbricated with the “slow violence” (Nixon) of chronic, systemic injustice. From drastic inequality to environmental destruction, many of the challenges the Philippines faces result from colonial and neo-colonial violences.

Frequently, emphasis on “sustainability” suggests a future-oriented focus on hunger–that actions we take to protect the environment today will have an impact on hunger in the future. But because hunger is so often understood as an immediate, pressing need of a population that lacks sufficient food in the here and now, concerns about both past and future are set aside (to our peril).

Grappling with hunger demands that we attend to both memory and futurity. On NPR, we heard a story about “hunger stones” now visible in the Elbe River in the Czech Republic. These stones, which record famine-causing droughts from 1416 onwards, only appear when river water levels are low, as they are today (Domonoske).

Laurie Beth’s ongoing research on trauma tourism has revealed the degree to which hunger is part of many of the forms of violence that are recalled by the memorials she studies.[6] Among the most famous depictions of hunger during the holocaust are the pictures of emaciated bodies of survivors that were taken at the liberation of the concentration camps. Gas chambers and crematoria may be more perverse, but hunger was a primary weapon of the Nazis.

Indeed, hunger has been weaponized throughout history, as it being weaponized in Gaza today. Siege warfare is recorded in the bible and in Greek tragedies. In the Irish Potato Famine, British colonial economic decisions wildly exacerbated natural conditions. Similarly, violence is at the center of the Ukrainian Holodomor, Stalin’s genocide by famine intended to suppress the Ukrainian independence movement in the 1930s. The National Museum of the Holodomor-Genocide in Kyiv is closed by the current war, which itself is having a ripple effect of raising grain prices and decreasing food supply around the world. Nevertheless, the understanding of hunger as a form of violence, rather than as a failure of nature or technology, is still contested.

In the Philippines, we were keenly aware of the intertwining of fast, spectacular violence and the slow violence of hunger; for example, one of our most important partners, AJ Kalinga Foundation (discussed below), ministers both to hungry people on the streets of Manila and to the surviving families of those murdered by police in “extra judicial killings” of the poor, ostensibly in service of a war on drugs.

While engaging with hunger and hunger action was a new challenge for us, it was not without precedent. A review of earlier projects reminded us that we first thought about hunger in our work long before the Foodways series was launched. In 2002, Laurie Beth created Versteckte Kinder as a memorial for Jewish children who survived the holocaust by hiding in the forest. In this project, we invoked the children’s hunger by placing small loaves of bread in each of the one hundred small houses scattered through the forest.

Ten years later, Laurie Beth and Michael returned to the same forest to create Grim(m) Essen for which we staged peripatetic conversations while enacting scenes from the fairy tales that featured food. These included the lentils that were thrown into the ashes to be picked out by “Cinderella” (Ashentputten), the fruit that could not be accessed by the “Handless Maiden” (Das Mädchen ohne Händen), the lamb’s lettuce that was stolen from the witch by Rapunzel’s father, and the multiple images of food (bread crumbs, gingerbread house, chicken bone finger) from “Hansel and Gretel”.

What emerged in this research were the pervasive images of the miraculous appearance of abundant food, which truly must have seemed like the best of all possible magic at the time the tales were collected. They demonstrate that hunger (or at least food insecurity) was integral to the lived experiences of the story-tellers. In response to our conversation prompts, many participants in the walks recalled years of hunger in Germany during and following the second world war.

In Manila, we read Filipino folk tales and found some very similar narratives that align magic with easy access to food: a stick that becomes a fish every time it is placed in a soup pot, yet never disappears or diminishes; a sugar cane field that matures in record time; betel nuts that act as messengers; beans that turn to gold; animals that regenerate the parts of them that are consumed. During our work in the Philippines, we had the serendipitous opportunity for Jazmin to read aloud from these Filipino tales for an audience in Germany at an exhibition of documentation from the earlier project.[7]

In our Foodways series questions about hunger emerged at some point in every iteration, some of which became more important to us in the context of our explicit focus on hunger in the Philippines. Often, the issue of food waste connected the projects to hunger, at times implicitly.

In Foodways Darmstadt (Germany), one of our local partners was Foodsharing Darmstadt, a student group that rescues food that would otherwise go to waste and makes it available for free to everyone in their community. We admired these folks for their initiative, dedication, and openness. We were intrigued to realize how much of their motivation could be recognized as aesthetic—wasted food appears ugly as well as unjust, it is “matter out of place”.[8] These activists are clearly motivated by a nonpartisan politics of justice and mutual aid, but they also taught us to look for an aesthetic dimension within hunger actions (foodsharing Darmstadt e.V.). Later in this essay, we discuss our work with Sagup Negros who also reclaim rejected vegetables to prepare meals.

In Foodways Melbourne (Australia), food waste again emerged in our conversations during our “compost workshop.” Because we were excavating participant’s own food waste as a prompt for storytelling, we learned a lot about the practical approaches and emotional investments we have around food that is not eaten. We wrote about this in our essay “Doing Food, Doing Climate” (Clark and Peterson). For that piece we found research suggesting that the amount of food wasted in the world is roughly equal to the shortfall. In other words, some experts believe that if we could find ways to eliminate food waste it would solve the problem of hunger. But our experience of people’s tendency to moralize about food waste is one of the reasons we’re suspicious of simplistic assertions that eliminating food waste would eliminate hunger–it’s too pat and involves utopian (often techno-utopian) fantasies about perfect systems.

This relationship between food waste and hunger re-emerged in our pandemic project, COVID Foodways. Interviewees talked about the early days of the pandemic, when we saw unsold milk being dumped on dairy pastures, livestock killed and buried in pits because they’d grown too big for processing machinery that had been closed for months, and long lines at food pantries.

In the United States, where Foodways Madison explored systems, the most explicit discussions of hunger were during our focus on food security. To our survey question “What would it take for everyone to be food secure?” we received many interesting answers, most demonstrating what we might call a “vernacular” systems analysis. That is, even “non-expert” people were quick to link food security to broader systemic questions of education, employment, and social justice more broadly.

However, during Foodways Madison, our most direct opportunity to provide meals for people who might need them was during our day-to-day presence as artists-in-residence in the public library, where many of Madison’s homeless spend their daytime hours. We often served pancakes or waffles or cookies or pickles. This is where the question of choice (about both the contents and the manner of eating) first came to our attention. It’s often presumed that people who are hungry should give up their preferences about what or how they eat, yet one of the satisfying things about our interactions with unhoused folks in our Community Research Kitchen was learning about specific preferences for what, when, where, and how to eat. This theme of agency, and related ones of pleasure and aesthetics, have become integral to our thinking here.

The Foodways series as a whole shaped our approach to the work on hunger. Foodways is premised on the idea that all people have food culture, that all kinds of eating are worth investigating, and that the most quotidian ways of “doing food” can invite consideration of the broadest historical, social, and political forces that shape those foodways. In light of that, what does it mean for hunger to have foodways? On our blog, written in the midst of the Philippines projects, we wrote:

[H]unger has its own foodways—as do efforts to mitigate it. Food may be eaten communally or distributed individually. It may be pre-packaged or home-cooked, familiar or foreign, healthy or expedient. The giver and the recipient may look for or avoid (eye) contact. The context may be somber or ludic. And there may be associated expectations—from prayer to measurement. Specific foodways take shape around these circumstances and objectives but are also shaped by the creative humans undertaking them. (Spatula&Barcode, “TARA NA!”)

To define hunger simply as inadequate access to food is to align human life with commodity value; instead, we agree with De La Salle’s Hunger Action Group that the human right to thrive means “a right not just to have access to resources, to be fed, but to exercise their human capacities to produce and create food for themselves and for others” (DLSU Hunger Action Group 3). Their attention to human capacity reinforced for us that the Foodways framework was, in fact, an appropriate and perhaps useful framework for understanding hunger and efforts to address it.

An even more important influence on our thinking early in the project was the aforementioned PSi27 conference which Llana organized.[9]

The framing and impact of this conference is discussed in more detail in the introduction to and reflection on these concurrent volumes of Performance Research and Global Performance Studies, but it seems valuable to record the strong impression that Llana’s leadership made on us, especially in her diplomatic but firm insistence that the conference be centered on literal hunger in all its varieties, rather than be potentially overwhelmed by discussions of metaphoric hunger (as a synonym for “desire”). This reinforced our aim to make a foodways project with hunger, in the midst of hungry people and people taking hunger action, rather than isolating cultural ramifications of hunger such as its representations in memory and narrative. We were worried that the work would be futile or even offensive, but we felt a necessity to find hunger foodways themselves.

Part of trying to approach this project with the humility it required was expecting a certain amount of partiality—we knew that the Hunger Action Group was connected with many more activities than we could possibly work with meaningfully, and that some connections would come to be more fully engaged than others. One of our working mottos is “say yes,” so when Jazmin and the Network offered connections, we took them up. All of them taught us something, and we hope we brought interesting questions, even when we didn’t develop further actions with them.

One of our first site visits was to Bagong Silang, a barangay (a Filipino word that means both neighborhood/community and political unit) in the northern Manila district of Caloocan. There the Federation of Persons with Disability and REKASAKA, a group made up of the families of people with disabilities, were holding a large event for hundreds of children in one of the open-sided municipal basketball courts common across the country. We were essentially spectators to the inauguration of a nutrition program for the children of these families. The long-term plan was to provide supplemental meals incorporating the “manna packs” distributed by the global NGO Feed My Starving Children; the purpose of this event was to establish baseline measurements of height and weight for the children involved (“stunting” is widespread among poor children in the Philippines). To create a festive mood and boost participation in the program, this event featured fast food super meals from the national chain Jollibee–rather than meals prepared communally by the parents of Rekasaka using the manna packs. The event featured games and activities and a performance by a literacy-focused children’s theatre troupe.

From our perspective, the event was eye-opening in terms of the way factors such as NGO grant metrics and donor involvement could shape the foodways of a community gathering. We were clearly adjacent to the “anti-hunger industrial complex” (Fisher) addressing the symptoms of systemic hunger, but in the midst of raucous, cheerfully playing children and their parents, we bracketed off our suspicions, just as we suspended our typical aversion to fast food. We saw people having fun in the context of eating together; this is the basic aspiration of most of our art projects.

We did not end up developing a project in Bagong Silang ourselves, but the opportunity to think about this connection to our work was an early point in an important line of thinking for us. Moreover, a kind of closure was provided when we learned that a meal program for this community was created during our later stay with Bahay Kalinga and we were able to join one of their preparation and distribution days (see below).

Another early encounter was a trip to the town of Lian, Batangas, where the university’s Lasallian Sustainable Development Program of the Center for Social Concern and Action has an established collaborative relationship with a fishing community that has developed its own sustainable fishing practices, including a mangrove nursery for restoration plantings, through the Lian Fisherfolk Association. We first met with local government officials, which gave us a sense of how such partnerships must operate within local politics, and then shared a lunch with a number of fishers. It was a delightful conversation, full of detail about their lifeways and livelihoods and insights into what it means to be a food provider living an economically marginal existence. Afterwards, we visited the mangrove sanctuary and sat down for still more conversation.

We were inspired by the beauty of the place, the liveliness of the talk, and above all by the sense of local agency and big-picture thinking of the Association members. We began to imagine returning to collaborate on some community gathering that might lend support to further community organizing; some of the locals promised that they’d enjoy teaching us to make Sinaing na Tulingan, the Batangas-specific iteration of the genre of sour soups found in countless variations across the Philippines.

As promising as the context seemed, it proved unworkable within our time frame due to changes in the local political landscape. Human geographers use the term “politics of place” to describe how social relations embedded in geographies can define both affordances and constraints, allowing us to understand what may be realized in a particular location at a particular moment. While the work did not produce a spectacular outcome or product, it was the kind of positive engagement with individuals and institutions that feels vital to our version of social practice. It was also a telling reminder of the difficulties of hunger action—if we found that a simple, celebratory art project was impractical in this specific context, how much more challenging are ongoing impactful hunger actions.

The politics of place also figured importantly in our experience in Ozamiz, where our partners were staff and students at a different La Salle University (same religious order, different institutional network) who have multiple outreach programs in neighboring communities. They have a tenuous relationship with an Indigenous community, the Subanen, with whom they would like to work more closely; it was suggested that underwriting a traditional meal might open the way for future collaborations.

More than a dozen students traveled with us to Penacio, where locals prepared a ritual meal of pig and chicken. Over the course of several hours, what emerged in conversation was that the profound needs of this community (and also perhaps their profound anger) could not be ameliorated through any simple collaboration between a college and a community. Rather, a change in government policies was necessary in order to both empower the community to work and to retain sovereignty over their ancestral lands. The event was both festive and eye-opening, especially for the students, who learned as much about what could not be simply fixed as they did about who their neighbors are.

While its results were primarily in conversations, we found the discussions productive. First, in creating a local gathering that was an enjoyable, “gratuitous” event, and second in provoking a passionate follow-up discussion among the staff and students involved. A number of participants who had grown up in Ozamiz said they had never grasped the displacement and disenfranchisement of the Subanen, and many seemed to be questioning assumptions about what community work could do, but we also sensed a clarification of their shared values and commitment. This engagement was similar to our project with Sagup Negros, described below, in that both involved underwriting and exploration or experiment by a group with a strong sense of its own values.

We spent more time working with various components of the A.J. Kalinga Foundation than any other hunger action. We made multiple visits to the Kalinga Center in central Manila, which makes and distributes meals for “street dwellers.”[10] The center is part of (and situated at) the offices of the Society of the Divine Word in the Tayuman neighborhood of Manila City. De La Salle University has a long record of cooperating with the center, which frequently welcomes other volunteers as well.

Prior to COVID, meals that were served at the center included a shower and counseling. During the pandemic lockdowns, the center redefined its operations to distribute packaged meals in the neighborhoods where the homeless were confined (as well as arranging housing for many). At the peak, one thousand meals per day were distributed. When we first worked at the center, it was transitioning from street distributions back to its program based in the center, but we helped package and distribute hundreds of meal boxes of rice, okra, and pork (with a separate preparation of chicken for Muslim participants).

On that first visit, we were especially impressed by the logistical expertise of the operation, supervised primarily by formerly unhoused participants in Kalinga’s development programs. The food was clean and nutritious and prepared with extraordinary efficiency. Before heading out to the distribution points, we all sat down to eat it together and approved it as tasty. At the distribution sites, we were struck by the long, self-organizing lines and the combination of respect and efficiency as recipients were guided through an improvised handwashing station and then received their meals from the back of a van. As we handed over the boxes, we discovered an impulse which repeated itself several times over the Foodways project, which was to thank those who were accepting food from us.

On subsequent visits, the Center had completed some renovations and was again welcoming about 200 people each day for a series of activities and services and a sit-down meal. Again, the logistics were impressive, with participants admitted thirty at a time and given numbered tickets. After they were individually interviewed so they could be referred to other social services, they watched animated fairy tales while waiting to be offered clean clothing, showers, and a grooming opportunity.

One of the most conspicuous features of the Kalinga space are the enormous mirrors. On the mirror that precedes the clothing station, a sign says Ngayo’y madungis mamaya maaring luminis (Today I am dirty, later I can be cleansed), while a sign on the grooming mirror following the shower reads Malinis na ako, pahahalagahan ko ito, magbabago ang buhay ko! (I’m clean now, I’ll appreciate it, my life will change). This affirmation was followed by a small group gathering for coaching on themes such as care; this was brief, voluntary, led by several different types of staff (brothers, employees, or volunteers), and seemed to usually end in a short group prayer.

Finally, guests presented their numbered cards and are given plates of food which they consumed at tables that accommodate small groups of three to six persons. Meals include unlimited rice (which the experienced cooks seem to predict the need for and to make quickly in enormous batches), a meat dish, a vegetable, and a simple dessert such as compote. This station is labeled “eating and bonding”, but bonding mostly occurs simultaneously with eating, since the pace of things means that folks must move along fairly quickly.

The most compelling aspect of this work was the direct interactions with those guests who came back to the food line for seconds and thirds, not only because this gave us direct interaction with guests, but also because it was one of the sites of what we would call a performance of agency–of guests asking for specific amounts of a particular dish, expressing a like or dislike of bananas, or even having the food placed onto their plate in a particular way.

As should be clear, Kalinga runs a smooth and efficient hunger mitigation effort, albeit one shaped to deliver religious education and values. To partner with this organization meant setting aside our critique of organized religion in favor of admiration for the efficacy with which a chronically hungry community is fed. Despite the somewhat patronizing tone of the mirror texts, the actual transactions with food recipients were respectful and characterized by listening more than preaching.

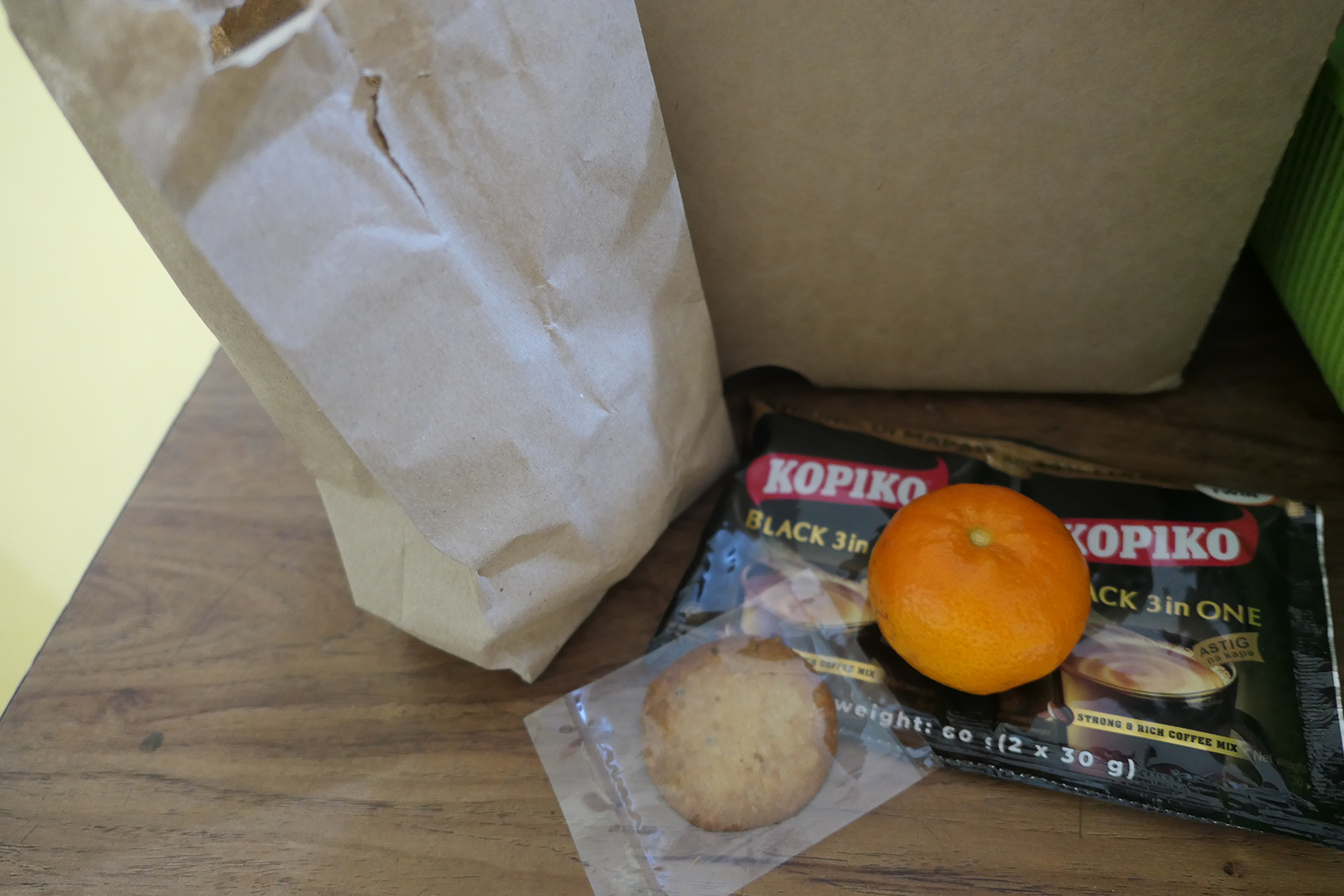

After several visits, we consulted with Kalinga staff about staging a non-disruptive intervention at one meal, at which we provided gifts and treats—small food items that we learned from center staff might be appreciated by food recipients that were not ordinarily part of the distributed meal. While we were confident to share fresh tangerines and specialty cookies donated by the gourmet restaurant Purple Yam, we were intrigued to learn that Kopiko instant coffee packets (sweet with milk powder) are prized for their capacity to sustain a hungry person on a day or at a time when they cannot get access to other food.

In addition to supplementing the meal, we also chose to “enhance” the “listening” component of the program.[11] For this, we enlisted a small team of De La Salle students to record responses to two questions:

These interviews, while they may become texts in some future project, were more important for the emphatic role that a microphone and/or camera can provide to a conversation as an indication to the interlocutor that their words are being heard and that they are important.

In addition to providing meals at the downtown Kalinga Center, the De La Sallian order also runs Bahay Kalinga, a newer endeavor that provides residential socialization and training to small cohorts of “unhoused” men that is on the grounds of a former hospital. We were able to share two meals with this group at their group home and to participate as they prepared and delivered packaged meals for some of the children with disabilities that we first met at Caloocan (see above). While we were merely bystanders to these efforts (providing only home baked bread and aprons for the workers), we recognized something we loved in driving through a neighborhood to greet people and offer them food.

In Bacolod, a city on the island of Negros, we worked with a group of recent college graduates and current students who, moved by their environmental concerns about food waste, founded a food rescue operation along with a small restaurant. As an offshoot of Youth Empowering Youth (YEY), Sagup Negros is supported for their social entrepreneurship by the Lasallian Social Enterprise for Economic Development (LSEED) Center which is how we came to know them.

The team lives communally, rescues[12] discarded produce at the market, and prepares daily delicious meals that they serve in a carinderia - a small, affordable, buffet-style restaurant on their front porch. In addition, they sell frozen packets of their signature spring rolls and take on some catering jobs. All the work is done by volunteers except for the head chef, who is paid. In addition, the market vendors receive compensation by weight for usable vegetables that would have otherwise gone to waste.[13]

On our visits to Bacolod, the three of us felt a strong sense of affinity with this group of idealistic young people who were acting on their beliefs. The group shared with us that their original vision to use rejected vegetables to provide free meals for those in need was undermined by the necessity to generate operating costs from the restaurant; we realized we could help them test their original idea. It seemed within our means to underwrite a pilot project in which the Sagup Negros prepared meals for a community facing chronic food insecurity—in this case children living in the neighborhood of Mambulok. For us it was a new way of thinking about what we could do as privileged artists, to put not just our creativity but our resources behind another groups’ vision.

In contrast to the well-established Kalinga operation, Sagup Negros is very grassroots and improvisatory. Our event with them was a “pop up” conducted under a tent to which children (and their parents) brought their own dishware and eating utensils. This lent the event a celebratory quality which was enhanced by the volunteer efforts of a group of theatre students with whom we had recently conducted a workshop at the Negros Museum.

For the meal, we commissioned ceramic bowls from a pottery collective in Bicol where Jazmin’s family lives. These were gifted to the meal recipients along with the soup that was served in them. The bowls had the words WALANG GUTOM imprinted. Revealed after eating the contents of the bowl, the phrase, which means “the end of hunger” in Tagolog, suggests the immediate satiation of the meal. But it can also be used to describe the more utopian “end of hunger” in the world. As well, it can be translated as the imperative: END HUNGER.[14]

The meal also included monggo (mung bean soup), okoy (vegetable fritters), the Sagup Negros group’s signature lumpia (spring rolls), fruit juice, and ponkan (tangerines), which were coincidentally one of the “luxury items” we added to the Kalinga meal. Cooking was done at a kitchen space that belongs to the Sisters of the Good Samaritan using vegetables that were rescued from the market. The meal itself was served in the neighborhood where the children live.

Considered formally, the event had a lot in common with many Spatula&Barcode events: a festive setting, celebratory food, entertainment interspersed with interaction, and even giveaway “swag.” What felt different to us was using resources we could muster to provide an incentive, as well as material support, to creative people who already had a vision of a specific form of hunger action.[15] That form of action has not continued—in addition to their food waste rescue operation, the group is currently focused on supplying a busy community food pantry—but for us the success of the project was the creation of a generous temporary space of commensality and conviviality that nourished the group’s sense of purpose as well as the children of the neighborhood.

Crucial to our analysis and critique of hunger action as it is ordinarily enacted is a conversation about agency. Early on in this project, we were reminded of the phrase “beggars can’t be choosers” which recurs in the experience of many children in English-speaking households to teach us that we should accept without question that for which we have not paid.[16] The phrase has its source in the 1500s when John Heywood recorded the proverb:

Beggers should be no choosers, but yet they will:

Who can bryng a begger from choyse to begge still?

where it seems to suggest a degree of agency on the part of the mendicant (and a social norm to suppress it).

The idea that recipients of “free” meals might have opinions about what they want to eat (as well as medical, religious, or ethical dietary constraints) runs counter to the parsimonious, moralizing attitude that informs much public discourse about relief work, which emphasizes frugality, efficiency, and perhaps most of all a punitive (or at least puritanical) impulse. The poor, it is suggested, deserve to suffer. Even the most generous affect of the givers of aid can play into what Andrew Fisher, quoting charity worker Robert Lupton, calls “toxic charity” (Fisher 49) and contribute to the “collateral damage […] to the psyche” that institutions such as food pantries can cause (46). On a broader scale, this attitude can be seen in the application of austerity measures to societies on whom global debt has already been imposed.

Why is hunger action so often tied up in austerity? During the financial crisis in the European Union, austerity measures were imposed on countries like Greece and Italy because it was felt these nations should “pay” for their neediness. In the United States, government food assistance (SNAP, formerly known as “food stamps”) is restricted by complex income calculations, and cannot be used to purchase vitamins or “Foods that are hot at the point of sale” (US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service; SNAP benefits average US$1.40 per person per meal (Center on Budget and Policy Priorities).

In the context of direct hunger actions, a wide range of austere or conservative practices are present. At many meal distribution sites we have witnessed, servings of rice are unlimited—workers would say “there is always rice”—but servings of meat and vegetables were modest and could even be described as meager. It’s not uncommon in the Philippines for meat and vegetables to be treated as a condiment accompaning rice, but it was also clear that at least a few recipients wish for more meat. Still, “there is always rice” is a kind of statement of unconditionality, an effort to set a basic ground of unconditional generosity.

When and how can hosts offer choice? Perhaps more importantly, in what ways do guests exercise limited agency within existing contexts? One of these ways is to ask for more food, or to ask for less food or different food, or to specify how they would like the foods to be organized on their plates: the sabaw (gravy) can go over or alongside the rice, for example. This seemingly insignificant exercise of preference came to loom large in our thinking about the interpersonal ethics of hunger actions as social practice. To state it most simply, one person giving even the most modest food to another can at a minimum collaborate with guests to within even the most constrained times and spaces.

Food sovereignty is a term that is gaining both visibility and traction in discussions of food justice. It is often used to describe a community’s right to produce, distribute, and consume healthy and culturally appropriate food (US Food Sovereignty Alliance). That community can be understood in terms of nation, demographics, ethnicities, neighborhoods, etc. It can be articulated in terms of power within global commodity distribution systems, or at the level of small urban gardens controlling their plots.[17] It has powerful resonance within many Indigenous communities, where sovereignty more broadly is so central to politics in relation to colonial power.

Does food sovereignty connect to food security? Is a person or people’s “freedom from hunger”, even if structurally guaranteed, sufficient without the power to determine what, where, and how they will eat? We have come to think of food sovereignty as most meaningful when understood across multiple scales, from whole nations to oppressed populations, down to individuals. This links sovereignty to the agency that is so crucial to understandings of voluntary self-starvation (see Brainard, Crews and Lennox, Disman, and Erincin in these issues) and which partially accounts for the moral impact of prisoner’s hunger strikes and the unique outrage against human dignity represented by force feeding (see Patrick Anderson’s article “Paradigms of Hunger” in the companion issue of Performance Research).

If we recognize possibilities for amplifying agency and sovereignty in even the most desperate hunger contexts, we’ve then identified an ethical obligation of the well-fed to the hungry that exceeds nutrition—we have a puzzle of conviviality and commensality (a Spatula&Barcode staple) to solve together. To be clear, it is better for starving people to have food, even if they cannot (are not permitted to be?) “choosers.” But this understanding of the potential in people for food agency and sovereignty as producing an ethical obligation among people suggests to us that food security without food sovereignty does not add up to food justice.

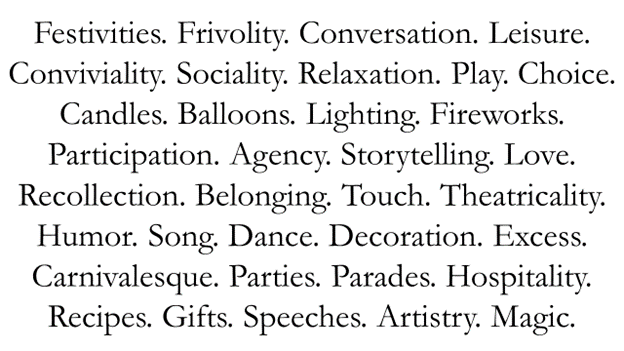

The arts are often associated with “excess,” and whether or not we agree with this assessment (we might argue that arts are essential), we can here turn it to an advantage by using the art frame to bring things to hunger actions that are most often overlooked: pleasure, frivolity, and choice. More specifically, we think this is one of the most important places where artists can contribute. When we ask what is available alongside food in contexts that are not “hunger action” we produce a much more robust list of accompaniments (see image below). We take it as a challenge to ourselves and to other artists to deliver these and other “excesses” as part of sharing nutritious and delicious meals.

We can think further with Jacques Derrida’s distinction between conditional and unconditional hospitality in this context. Conditional hospitality, grounded in the law, “recognizes and tolerates the guest, but also reminds the guest that she is not in her own house” while unconditional hospitality “signifies a radical openness to an absolute, indistinguishable other” who is regarded as a liberatory force. As one reviewer of Derrida’s text summarizes it, “the guest is viewed as a liberator that brings the keys to the prison of the nation or the family. In this sense the host is the deficient being who views himself as a parasite—and eagerly encourages the awaited guest to step inside as the host of the host” (Rafn).

In Foodways Philippines, we perhaps just glimpsed how those we served offered us something to address our deficiency; this certainly aligns with the sense of gratitude we’ve often felt when feeding others. From certain religious perspectives, it is the doers of good works who are indebted to the recipients. Recent psychological research also emphasizes the value of giving to the donor or caring to the giver (Rancaño).

We’ve been interested in the notion of “radical hospitality” since Laurie Beth first came across the phrase as a visiting artist at St. Norbert College. This Catholic institution invokes biblical injunctions to welcome strangers as a basic tenet of campus life. Most progressive Christian individuals and organizations seek to emulate Christ’s model of radical hospitality, as do other churches and religious groups: Benedictine, Benildian, Jewish, Methodist, Moslem, and more.

More recently for us, “radical hospitality” was invoked by Richard Gough in his keynote address to the Performance Studies international conference on hunger (published in this volume), where he used it in reference to projects by chefs like Massimo Bottura and José Andrés that provide extraordinary dining opportunities to people who are not in a position to pay for meals. These chefs directly challenge the more common association of hunger with austerity.

Like austerity, other values are often delivered alongside food aid. For example, a report on homelessness in the Philippines from the US antipoverty group The Borgen Project lists poverty, domestic violence, human trafficking, and natural disasters as causes of homelessness, yet its concluding section on “addressing” homelessness lists a single government cash assistance program and goes on to discuss two groups that “teach children about hard work while providing them with an income” and “teach kids on the basics of hygiene”—as though lack of knowledge rather than lack of access to sanitation facilities and economic opportunity were the issue (Philipp).

We heard some similar value judgments expressed during our work in the Philippines (and frequently see similar attitudes in the United States and Europe) where it is suggested that people needed to be willing to give up their “street values” and subject themselves to “formation” if they were to be allowed to join a program that offered housing, education, and job training.

None of the values that forms of hunger action espouse (sociality, education, cleanliness) are particularly troubling to us, nor have we seen them delivered in a heavy-handed way. Every interaction we witnessed was gentle and attentive rather than preachy or coercive. Still, if the arts and humanities have a contribution to make to hunger action, the extent to which something is expected of the guests in return bears examination. We also wonder: If something defined is expected in return for the meal, does it make the hospitality less radical? On the other hand, might some of those in line hunger for more than food?

We continue to contemplate where we can insert ourselves into hunger actions without disrupting either its mechanisms or its value systems, and what we can take forward from our experiences to think about other events we can devise that engage hunger in other contexts. We are wondering if we might introduce some playful and creative stations into a pragmatic, pedagogic, or theological lineup like Kalinga. We like imagining our own inviting and inclusive architectures for hunger action (like the Bottura refractories Richard Gough describes in his keynote article). We may also play with the re-performance of some of the structures of hunger action in other theatrical and artistic contexts because we do think that feeding people is both a beautifully simple act and an incredibly difficult thing to do.

We applaud “political” or “activist” arts projects that aspire to more than this, but by the time we had to leave the Philippines, we defined our own work there as acting out of this impulse to “add something” to the work others were already doing. Not to critique it, tinker with it, or consult about it, but to practice moments of hospitality (understood as a relation of mutual dependency and possibility) alongside it.

This led us to the term lagniappe (pronounced lan-yap) to refer to aspects of our work in which we provide “a little extra” to existing activities and institutions. We were learning that in contexts where we are outsiders, it may be more valuable to participate in and enhance ongoing efforts rather than to invent new ones ourselves, and this approach has been reflected in most of the projects we have done since 2022. The Dictionary of American Regional English defines “lagniappe” in its broadest sense as “anything extra thrown in for good measure”. If a well-fed tourist receives a free beignet with a cup of coffee in a New Orleans cafe, this notion might seem inconsequential. But thinking of small gifts, moments of celebration, or acts of listening as thrown in “for good measure” is our modest way of understanding these Foodways projects as going beyond “what is required” but not as immaterial or meaningless.[18]

While we have always written our group name using an ampersand (except in our web addresses, where it’s not allowed), the ampersand has grown both in size (in our logo) and in importance (in our work). The ampersand began clamoring for attention immediately following the 2016 election of Donald Trump in the United States. In a project called “Rage Grief Comfort &” we invited audience members to use food to express their emotional responses to the election outcome and then sent them on their ways with an ampersand cookie and an admonishment to take further action beyond the affective (Spatula&Barcode. “Rage Grief Comfort &”). We continued through the ensuing protest season to provide ampersand cookies to participants.

In projects since 2016, but especially in those where we join with other groups, the ampersand may refer to the “lagniappe” we are providing to an existing activism. But we have also been using it recently to recognize the work of others who do something extra beyond. For example, just recently we collaborated with the Milwaukee exhibit “Growing Resistance” by using the ampersand in an awards ceremony (both as medals and as giant cookies) to recognize the lifelong labors of fifty individuals who has served as “community guardians” by sustaining urban gardens, providing meals, fighting for housing rights, and in other ways serving Milwaukee’s less affluent neighborhoods. Beyond a simple conjunction, the ampersand has come both to symbolize the role of the arts as a potential enhancer (or force multiplier) of social action and also to represent and honor the ways in which activists (and others) go “above and beyond” to make the world better.

Just as most artistic projects in the context of hunger actions cannot hope to make a substantial change in the problem of hunger,[19] neither does considering the ethical obligation to offer agency or hospitality alongside food promise a revolutionary new sovereignty. But if the most impactful hunger actions both relieve immediate hunger and build social capacity (and perhaps political will), then artists’ participation can perhaps be understood as an opportunity to practice conviviality, to be together within a tiny, fleeting zone of freedom.

While we will not be able to mention everyone who paved the way for us, welcomed us, and schooled us in the Philippines in 2022, we do want to try to call out some of the key collaborators by naming individuals and organizations:

Ariel Casihan, Alvin Jonson, Awit, Bea Concepcion, Brother Armin Luistro FSC, Brother Butch Antolin Alcudia FSC, Carl Vincent Cordera, Colline Lazona, Denise Mordeno Aguilar, Edgar Jonson, Eric, Fr. Flavie Villanueva SVD, Franz, Fritzie Ian de Vera, Genrick Catalonia, Grace Aganon, Jay R., Jewel Guzman, Jian Tan, Joann Salubre Uy, John Patrick Plaida, Jorem Yap, Joseph Peji, JR, Katherine Taleon, Kelen Razote, Lance Yu, Leo Tadena, Lyssa Tomayao Pardillo, Marciano M. Laurel, Mariel Casildo, Neil Penullar, Noel Pahayupan, Norby Salonga, Ofelia Rodil, Paula Zaldivar, Raven Cheyenne Salanap, Rayne Trisha Trinio, Reigner Sanchez, Renna, Renz Banaston, Reynante Agquiz, Ritchie Balgos, Richie dela Peña, Roderick, Tanya Lopez, Ted Villanueva, Tessam Castillo, Trisha Concepcion, Weniwilson Amora, Zaldy Lainez, Arnold Janssen Kalinga Foundation, Bahay Kalinga, De La Salle University (Manila), La Salle University (Ozamiz), Lassallian Social Enterprise for Economic Development Center (LSEED), Performance Studies international (PSi), Purple Yam Restaurant (Manila), Sagup Negros, Society of the Divine Word, Tulong Lasalyano, University of St. La Salle (Bacolod), University of Wisconsin-Madison

[1] See Allan Kaprow, Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life and Suzanne Lacy’s introduction to Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art. The literature on “social practice” art is wide, but Shannon Jackson’s Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics charts many of the crucial insights and issues in the field. Nato Thompson’s Living as Form effectively brings art/life and social practice work together.

[2] While Spatula&Barcode is the ongoing creative identity of Laurie Beth Clark and Michael Peterson, we frequently collaborate with other partners. In the case of Foodways Philippines, all the work was done in partnership with Jazmin Llana. Extensive documentation and writing about our work, as well as links to publications, can be found on our website at www.spatulaandbarcode.art and our blog www.spatulaandbarcode.wordpress.com). Portions of this essay are adapted from posts there.

[3] This essay is illustrated with some of the many photographs we made during the residency. We always photographed with the consent of our hosts and participants, but the question of informed consent is complicated when considering subjects whose presence within a hunger action context is driven by need. At the same time, we respect the agency of those we interacted with (and cooked, fed, and ate alongside of) in choosing to be part of our visual work. In this essay we have included photos of identifiable people only when they were very active in public hunger actions and/or explicit in their participation in our image making.

[4] Our theoretical orientation is informed by more expansive elaborations of social practice such as Grant Kester’s.

[5] For a useful discussion of the history of this term, see Laudan).

[6] See, for example, Clark; our joint essay on the dynamics of site-specificity in trauma memorials is forthcoming in The Routledge Companion to Site-Specific Performance.

[7] “Remember Hunger,” in KUNST NATUR WANDEL, Schader Galerie, Darmstadt, Germany.

[8] Mary Douglas develops this phrase as a definition of “dirt” and argues that “Where there is dirt there is system. Dirt is the by-product of a systemic ordering and classification of matter” (36)—an insight applicable to the place of food waste within food systems.

[9] The conference was entirely online, but to our memory it is “PSi Manila” because we were there in person to witness Jazmin’s extraordinary labors and those of the brilliant team she assembled.

[10] A.J. Kalinga often uses the term “clients” to refer to the recipients of the free meals and “members” to refer to indicate those involved in their multi-step programs (AJ Kalinga Foundation). According to Architectural Digest, the Associated Press updated its stylebook in 2020, rejecting the term “the homeless” as dehumanizing and instead recommending the use of “homeless people” or “people without housing” (Slayton). “Unhoused” is another common term and one that does better to recognize that some people do think of a particular street location as their home even when there is no stable shelter to contain them. In the Philippines, we often heard “unsheltered” or “sheltering on the streets” used by service organizations. “Street people” is usually seen as a degrading term, but it has a certain accuracy from the point of view of those with privilege, since “those people” are almost by definition encountered on the street (see our earlier observation about libraries as extensions of public space). Over the course of this work, we have used “guests” to refer to the hungry and those in need. Our choice of this term is a considered one, elaborated in an essay on our blog, titled “Can Beggars Be Choosers?” In brief, we chose “guests”, rather than common terms such as “the homeless” or “street people”, because we wanted to denote our relationship (of hospitality) rather than an assumption about their residences. See more about hospitality in our conclusion.

[11] Listening is also an ongoing part of the Spatula&Barcode repertoire. See for example Orecchiette, an iterative project in which we make ear-shaped pasta with groups who are listening to one another.

[12] “Sagup” in Cebuano can mean “rescue”, or “take care of.”

[13] The group’s interest in waste mitigation is driven primarily by environmental concerns but hearkens back to our discussion of the connection between hunger and food waste in earlier projects.

[14] We distributed these bowls in other locations where we worked as well, including Ozamiz, and it gives us pleasure to imagine the daily use of these objects and their circulation in multiple Filipino communities.

[15] While the entire approach of social practice art moves us away from a modernist valorization of individual “genius,” the prospect that artists might engage in work that does not foreground “originality” is a further intervention.

[16] In Stuffed and Starved, Raj Patel reminds us that this thinking extends well beyond individual desire to define policy for food aid on a global scale (161).

[17] In Raj Patel’s phrasing, “Across a range of places and circumstances, we are not sovereign. Reclaiming control of the food system requires both an individual and a collective effort, and requires both individual and collective rights” ( 308).

[18] Another way to track this is to reject the idea that “culture” is simply an unimportant outgrowth of material “base.” Understood not as decoration but as participation in the social, these “lagniappes” are constitutive, however slightly so, of how it is to coexist in society.

[19] This is not absolute—see Llana and ARMK in the companion issue of Performance Research.

AJ Kalinga Foundation, https://ajkalingafoundation.org/.

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. “Chart Book: SNAP Helps Struggling Families Put Food on the Table.” November 7, 2019. https://www.cbpp.org/research/food-assistance/snap-helps-struggling-families-put-food-on-the-table-0

Clark, Laurie Beth. “Coming to Terms with Trauma Tourism.” Performance Paradigm, vol. 5, no. 2, 2009, pp. 162–84.

Clark, Laurie Beth, and Michael Peterson. “Doing Food, Doing Climate.” Performance Research, vol. 23, no. 3, Apr. 2018, pp. 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2018.1495945.

Dictionary of American Regional English. “Lagniappe.” https://www.daredictionary.com/view/dare/ID_00034244?q=Lagniappe

DLSU Hunger Action Group. Framework for Hunger Research and Action. 2020.

Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. Taylor & Francis, 2002.

Fisher, Andrew. Big Hunger: The Unholy Alliance Between Corporate America and Anti-Hunger Groups. MIT Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10987.001.0001.

foodsharing Darmstadt e.V. “Willkommen bei foodsharing in Darmstadt!” https://foodsharing-darmstadt.de/

Jackson, Shannon. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. Routledge, 2011.

Kaprow, Allan. Essays on the Blurring of Art and Life. University of California Press, 1993.

Kester, Grant H. The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context. Duke University Press, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822394037.

Lacy, Suzanne. “Introduction: Cultural Pilgrimages and Metaphoric Journeys.” Mapping the Terrain: New Genre Public Art, edited by Suzanne Lacy, Bay Press, 1995, pp. 19–47.

Laudan, Rachel. “Foodways and Ways of Talking about Food.” 16 February 2017, https://www.rachellaudan.com/2017/02/19542.html.

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard University Press, 2011, https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674061194.

Patel, Raj. Stuffed and Starved: The Hidden Battle for the World Food System. Melville House, 2012.

Rafn, Soren. “Jacques Derrida: Of Hospitality.” visAvis, 27 February. 2013, https://www.visavis.dk/2013/02/jacques-derrida-of-hospitality/.

Rancaño, Vanessa. “Be Kind, Unwind: How Helping Others Can Help Keep Stress In Check.” NPR, 17 December. 2015. https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2015/12/17/460030338/be-kind-unwind-how-helping-others-can-help-keep-stress-in-check.

Slayton, Nicholas. “Time to Retire the Word ‘Homeless’ and Opt for ‘Houseless’ or ‘Unhoused’ Instead?” Architectural Digest, 21 May 2021, https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/homeless-unhoused.

Spatula&Barcode. “Rage Grief Comfort &.” Lateral, vol. 6, no. 2, 2017, https://doi.org/10.25158/L6.2.12.

———. “TARA NA!” Spatula&Barcode, 20 June 2022, https://spatulaandbarcode.wordpress.com/2022/06/20/tara-na/.

———. “Can Beggars Be Choosers?” Spatula&Barcode, 17 August 2022, https://spatulaandbarcode.wordpress.com/2022/08/17/can-beggars-be-choosers/.

US Department of Agriculture Food and Nutrition Service. “What Can SNAP Buy?” https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/eligible-food-items

US Food Sovereignty Alliance. “Food Sovereignty.” https://usfoodsovereigntyalliance.org/what-is-food-sovereignty/. Accessed 26 March 2024.

Thompson, Nato. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991–2011. The MIT Press, 2012.