In this article I examine hunger as a form of artistic performance, a conscious choice to avoid food for spectacle rather than an unwanted need arising from lack of basic nourishment.[1] But how can a negative action, the decision to abstain from food, be enacted on stage?

It has been noted that hunger and spectacle look like strange, even incompatible bedfellows. In her The Art of Hunger: Aesthetic Autonomy and the Afterlives of Modernism (2018), Alys Moody acknowledges that “by its nature, hunger makes an unsatisfying spectacle. Characterized only by an absence—by the refusal to eat over long periods of time—it is by definition unobservable” (42). This undramatic quality of hunger and the challenges it poses to conceiving of its performance were already brought up in 1999 by Enzo Cozzi, who argued that hunger as “the pressing presence to an organism of the absence of sustenance […] cannot even be represented. It must be deployed maskless, bare” (121–22).

And yet, the performance of hunger can indeed be staged effectively, as I illustrate with two relatively recent examples, the play The Hunger Artist Departs (Odejście głodomora, 1977) by Polish poet and playwright Tadeusz Różewicz and the production of A Hunger Artist (2017) by the contemporary NYC-based company Sinking Ship.[2] Both are inspired by what is perhaps the most famous literary account of artistic fasting, the short story “A Hunger Artist” (“Ein Hungerkünstler,” 1922) by the German-speaking Jewish author Franz Kafka, itself modeled on historical examples.

To understand how hunger can become stageable action, it is then crucial to shift to a broader view, not limited to an isolated performer’s act but encompassing a larger set of agencies. If hunger by itself is indeed difficult to represent, it calls for others to make it more observable. Sociologist Bruno Latour, along with other proponents of actor-network theory (ANT), points out that an actor/agent is always also a network, “not the source of an action but the moving target of a vast array of entities swarming toward it. […] To use the word ‘actor’ means that it’s never clear who and what is acting […] since an actor […] is never alone in acting” (46).[3] It should be added that, in line with posthuman thought, ANT insists on including non-human actors for a comprehensive perception of the totality of agencies involved. In other words, to understand any actor, we really must take into account the network of all other connected actors involved in the production of a certain outcome. However, because an actor-network’s action is “dislocated” and therefore its sources remain uncertain (46–47)—i.e., they are often invisible, as they act from other places and times—one of the most exciting aspects of an ANT analysis is to reveal the “many surprising sets of agencies that have to be slowly disentangled” (44). Here, I show this process of progressive discovery of hidden actors through two dramatic adaptations of Kafka. In fact, a major difference between his short story and its adaptations for the stage—as we will see—is the type and number of actors that can be discerned, the weight accorded to them, and through what means they accomplish the task of framing hunger as spectacle.

As for the frame provided by these interacting actor-networks, it should be noted that we are speaking of at least two conceptual layers superimposed on the simple act of fasting. In his study on the organization of experience, Erving Goffman details how distinct levels can be extrapolated from the primary natural and social frameworks that constitute reality by “keying,” a process of transcription “by which a given activity, one already meaningful in terms of some primary framework, is transformed into something patterned on this activity but seen by the participants to be something quite else” (43–44). For Goffman, deliberate starvation would belong to a primary social framework because—as opposed to a natural one—it can incorporate “the will, aim, and controlling effort of an intelligence, a live agency [… which] is anything but implacable; it can be coaxed” (22). To function as spectacle, however, both hunger and its mastery have then to be explicitly keyed/framed as performance, “made available for vicarious participation to an audience” (53). Indeed, hunger artists offered an example of “stunts that individuals can learn to perform with their physiology” (28). Obviously, when a work of art further keys this spectacle of an act for presentation on stage, it adds yet another layer or “lamination” (82) to the framing of reality, and results in cases of theatre-within-the-theatre. In sum, there is fasting itself; how it was deployed as spectacle by the historical hunger artists; and the way their performances were represented in literature and subsequently transferred to contemporary stages.

Thinking of this process of artistic creation and adaptation in terms of ANT, which has been aptly described as a “sociology of translation” (Callon 67),[4] we can see that the historical hunger artists who inspired Kafka were actors who influenced and were somehow translated into the contents of his short story, just like the short story itself became an essential actor as the hypotext for its (performative) hypertexts, to use Gérard Genette’s terminology (5). Thus, although Kafka did not face the challenge of enacting hunger on stage, his short story operates here as an “obligatory passage point” (Callon 70) that precisely interpellates the type of performers and performance genre that were handed down (i.e., translated) to its later “intermedial adaptations” (Laera 6). But before turning to the artistic renditions by Kafka, Różewicz, and Sinking Ship, let’s look at the historical artists’ strategies for the performance of hunger, the first lamination of fasting as spectacle.

To briefly outline the Western context that Kafka drew upon for his short story, hunger as entertainment appeared in Europe and the United States mainly in the form of two types of performers: the so-called living skeletons and hunger artists. The former “exclusively derived their appeal from their extreme thinness; only the body wasted to the bone was presented as a horrible attraction” in the category of living natural wonders or “freaks of nature” (Vandereycken and van Deth 77). By contrast, the latter earned their living through fasting on stage and made no secret of their lucrative intentions. In fact, they employed an impresario or a manager to gain maximum profit. Hunger artists were thus unique because, in Sigal Gooldin’s words, they engaged in “a spectacle of both hunger and of its mastering […] a spectacle of an act, of doing, as opposed to the spectacle of ‘being,’” performing “restraint, will-power and self-discipline” in a “modern spectacular version of the disciplined self” (47).[5]

Although some known examples go as far back as the sixteenth century, “the heyday of the art of fasting was undoubtedly the last two decades of the nineteenth century” (Vandereycken and van Deth 83), spurred by the experiments of American physician Henry S. Tanner. After overcoming shorter week-long fasting challenges, he eventually undertook a successful forty-day fast in New York in 1880. Despite many who questioned Tanner’s integrity, medical supervision, occasional strolls outside, and a physical condition considerably different from the expected emaciation at the end of his feat, because of his success and considerable earnings from admission tickets, many imitators soon followed in his footsteps.[6] The most famous of them in Europe was the Italian hunger artist Giovanni Succi (Mitchell 239), who convinced Luigi Luciani, professor of physiology at the Institute for Advanced Studies in Florence, to provide scientific supervision for his thirty-day fast and to form two commissions to oversee him, “‘with a considerable attendance of prominent Florentine physicians, a large number of medical students, lay citizens and newspaper reporters,’ and two volunteers who observed Succi day and night” (Nieto-Galan 71).[7] This type of scientific frame was just one of the ways Succi cultivated a super-human persona and boosted his lucrative business as he “displayed his skills […] in theatres, exhibition pavilions, scientific societies, [and] public parks” (69). Clearly, the social dimension and the spectators’ gaze were key to this type of performance,[8] which could entail side-shows to prove the performer’s unique resilience. For instance, in 1888, “on the 27th day of his fast, Succi performed a fencing display at the Teatro Imperiale [in Florence] to demonstrate the impressive stability of his muscular strength and his physical condition, and attracted more than 2,000 members from the higher echelons of the city” (78).[9] Ultimately, all these events were part of a broader experiment every hunger artist engaged with, the challenge to fast as long as possible in the face of death itself.[10]

Before this form of spectacularized hunger lost audiences to other types of entertainment, there was a final peak of interest in the 1920s. Hunger artists must have been really popular in the German capital, Berlin, if in 1926 as many as six hunger artists were performing simultaneously. Of particular interest because of a frame that intensified the drama between eating and not eating was the restaurant Zum Goldenen Hahn, which—in the middle of the hall occupied by “corpulent gentlemen and fashionably dressed ladies […] consuming Wiener Schnitzel with fried potatoes”—placed an elegantly dressed hunger artist, under a glass bell, who smoked cigarettes and occasionally sipped from a glass of water, with a blackboard counting the days of his fasting at his side (Bouman 249, qtd. in Vandereycken and van Deth 89).

Kafka only lived in Berlin for a short period of time between 1923 and 1924, and therefore after writing his short story, but of course printed materials like periodicals and photographs could furnish him with a great deal of information on this type of performers. For instance, Breon Mitchell suggests that several details of Kafka’s short story may have been inspired by Succi (244) and Astrid Lange-Kirchheim provides further clues as to how a widely distributed Viennese magazine describing an 1896 performance by Succi in the Austrian capital could have survived in the archives and become a precious source for the author. Leaving aside a wealth of biographical, psychoanalytic, or metaphorical interpretations of his short story, for example about the marginal role of artists in society or relating to a writer who saw himself as “the thinnest human being I know” (qtd. in Vandereycken and van Deth 237), let’s have a closer look at Kafka’s take on the hunger artist with a specific focus on how the historical performance genre was translated into his own literary rendition. As explained earlier, since most of the elements he chose to portray continued their journey into subsequent dramatic adaptations in one way or another, the short story acted as a key passage point in the genealogy of translations that has contributed to keeping the genre alive.

Kafka’s short story lays out the essential components of a hunger artist performance, while delineating the gradual shift from the genre’s days of glory to a decidedly more marginal position, leading to a dramatic shift of frame. However, his attention throughout is tightly focused on the hunger artist himself and only a few of his very limited visible actions. Other actors, human and non-human, are mentioned but much less defined—unnamed, grouped into general categories, or even apparently inactive—their point of view never really explored.

The story begins with an anonymous narrator explaining the art of fasting’s irreversible decline, in stark contrast with the excitement evoked by hunger artists in the recent past, when an eager audience in awe would even buy “season tickets” (Kafka 188). The performance would take place in the confined space of a cage, its floor strewn with straw, whose bars were wide apart enough to let the artist extend an arm out for people to feel how thin it was. This action is the most dynamic act between performer and audience explicitly described here, providing a direct sensorial experience for the spectators.[11] For the rest, the artist’s behavior was rather muted, consisting mainly of sitting there “pallid in black tights, with his ribs sticking out […] sometimes giving a courteous nod, answering questions with a constrained smile, […] and then again withdrawing deep into himself, […] staring into vacancy with half-shut eyes” (188–89). The exception would be the occasional episodes of the artist growing irritable, even shaking his cage’s bars like a wild animal, if a spectator suggested that his melancholy was caused by fasting; to the contrary, he just regretted the forty-day limitation imposed by the impresario, worried of the audience involvement’s inevitable dwindling after that period.

Additionally, the performance setup entailed a group of three alternating “permanent watchers” sitting at a table (189), usually butchers, selected by the public to check on the artist day and night. In truth, the hunger artist welcomed these vigilant monitors because they guaranteed his honesty and enhanced his professional value: he enjoyed “exchanging jokes with them” or singing to prove he was not secretly nibbling on any food; and even compensated them by offering “an enormous breakfast” (190). Their surveillance and eating thus become central components of such a performative assemblage, increasing the differential between the lack of action embodied by the fasting artist and the butchers’ antagonistic activities. A detailed account of the fortieth-day ceremony follows: along with a full-fledged military band playing to enthusiastic spectators, the ritual included two doctors to measure the effects of fasting and announce the results through a megaphone; two young ladies, who carried the artist’s weakened body to his first “carefully chosen invalid repast” (192); and the final toast initiated by the impresario to officially conclude the performance.

However, Kafka continues, once audiences deserted these standalone performances in more recent times, the hunger artist accepted a mediocre contract with a large circus that placed his cage “not in the middle of the ring as a main attraction, but outside, near the animal cages” (197). Such radical change of frame meant that most visitors neglected him and just rushed to see the other cages nearby. Eventually, “the fine placards” describing the meaning of his cage and performance “grew dirty and illegible” and the board counting the number of fasting days stopped being updated (199). Thus, the hunger artist—despite the freedom to surpass the forty-day limit—ended up dying of starvation, right after revealing the unexceptional motive of his fasting, his inability to find food he liked. Once the circus overseer substituted the attraction in the cage with a mesmerizing young panther, its “joy of life” and “ardent passion” shocked and yet captivated the spectators (201). The contrast between the late apathetic hunger artist and the energy of the new occupant of the same stage could not be starker.

A few other non-human entities are mentioned by Kafka, but their agencies are not always developed into more visible, potentially stageable actions. For Latour, “a good ANT account is a narrative […] where all the actors do something and don’t just sit there” (128) and, therefore, can be viewed not only as transparent, inert “intermediaries” but instead as more active “mediators” (39). In particular, “the continuity of any course of action will rarely consist of human-to-human connections […] or of object-object connections, but will probably zigzag from one to the other” (75). ANT theorists further clarify that a network exists only as it is performed.[12] We have seen above the enraged rattling of the cage as an example of performance showing this continuity: hunger artist–cage–spectator. However, other objects just sit there. For instance, within the hunger artist’s immediate network in the cage, a tiny glass of water could imply at least his occasional movement to moisten his lips, attracted by the vital liquid; or, a ticking clock regularly striking the hour suggests that he would look at it frequently or wind it sometimes over the course of the extended performance. But scenes involving these potential non-human actors as more dynamic mediators in the performance of hunger were not portrayed by the author.

Overall, in terms of adaptation theory’s “modes of engagement” (Hutcheon 38–52), the short story shifts from the “showing” of the historical hunger artists to the “telling” of literary prose: in the process, the variety of social spaces that would have been open to a performer like Succi are condensed into a single location, the isolated cage under surveillance. While impoverishing the richness of potential performance networks for the artist, Kafka’s choice at least results in a tighter unity of place and action. This condensation of the genre’s chronotope has been the starting point for the subsequent dramatic adaptations that I will now discuss, and that went back to “showing” again, with Sinking Ship also adding “interacting” with the real audience. In so doing, Różewicz and Sinking Ship expanded their vision to encompass a larger number of actors in the hunger artist’s network and more manifestly demonstrated the framing of his action by others. The strategies they used, however, are quite different: whereas Różewicz employs a more writerly approach that expands the number of characters and their dialogic exchanges, Sinking Ship stays closer to the short story but amplifies the role of human performers and several non-human performing objects.

In The Hunger Artist Departs Różewicz, widening the focus, increases the awareness of the artist’s extended network as he explores interactions between human actors absent in or only implied by Kafka. He also fleshes out the motives of those already mentioned in the short story. By intensifying the contrast between the crassness of certain characters and the artist’s alluring ascetism, the play demonstrates how not eating can indeed become active, generating an aura that attracts the impresario’s wife, a completely new character not in Kafka. The play’s author also reveals more minutely the economic side of managing the hunger artist’s enterprise, along with the network of active agents necessary to frame his passive fasting as spectacle and produce income and food for others.

The play is divided into nine parts. The first two—a prologue by the author and a conversation between the hunger artist and a young woman on a bench in front of the curtain—bring up the rivalry between the hunger artist and others in the same profession. “Naturally, our Hunger Artist (the unique and chosen),” writes Różewicz in the prologue, “will never, never, acknowledge in his heart of hearts the existence of another hunger artist who is his equal in everything, including privations and sins” (76). Instead, he sounds wary of other contemporary artists, despising their clubs and associations and pitting their “worldly fasting” against the “real fasting” he practiced while living for twenty years in a cave (95)[13]; he has no interest in imitators, followers, or pupils, and argues that forty artists in his cage would make no sense because he exists exclusively in relation to well-fed people: he fasts for them to “have fun at my expense and also enjoy themselves” (79). Despite the markedly different context, by observing the larger network of performers in the same genre, Różewicz thus points to a similarity between the hunger artist’s approach and the nineteenth-century “great actors” of the regular theatrical circuit, who insisted on being the only stars of the show, were in competition with other stars (as in the famous case of Sarah Bernhardt and Eleonora Duse[14]), and often surrounded themselves with a less talented cast rather than hiring others who could overshadow them. In other words, the playwright shows how one of the strengths of these star performers could be the ability to carefully choose their network associations in order to highlight their uniqueness.[15]

But of course, even as the sole performer of the show, Różewicz’s artist is not really alone. Scenes 3 and 4 give voice to both the butcher-guards and the impresario, here portrayed as “a huge, monstrously fat man” (84). A night scene in almost total darkness, in which the artist sings a song to prove he is not eating, is followed by a morning demonstration of how the butchers devour a hearty breakfast, sucking out bone marrow and eating raw meat from a bowl. Compared to Kafka, the distance between well-fed people and the hunger artist is thereby made more dramatic by the impresario’s extreme fatness and the grotesque materiality and messiness of the food that can be shown on stage: while the hunger artist aspires to asceticism, the butchers not only work with meat but also consume it gluttonously. In this context, fasting thus becomes a spiritual virtue as opposed to the vice of eating too much. Clearly, such stark contrast could challenge the spectators as well, faced with the ethical dilemma of either identifying with the ascetic artist or reevaluating their own role in the consumption of (too much) food.

Then, after scene 5 in which several passers-by and potential spectators speak of food and diets in front of the cage, with scene 6 we are introduced to the impresario’s financial worries, which point to the necessary money flows interacting with the hunger artist’s network: he fears that ticket sales “won’t even be enough for food soon” and criticizes the artist’s passive fasting as a sign of conceit, not humility (91); he then lists all things that cost him money such as upkeep, taxes, advertising, or currency devaluation, revealing how the artist’s apparent inaction and the entertainment frame built around him are in fact networked with several very active and financially risky tasks by others. Once his wife retorts that she cleans the cage for no extra money, the guards are unpaid, and Ernest the hunger artist eats like a sparrow, they begin to bicker; fearing betrayal, the vulgar and gluttonous impresario threatens violence against the artist and rebukes his wife for behaving like a foolish teenager.

At this point, Różewicz seems to point to how the fasting itself performs because of the aura it produces, in this case by rendering the artist magnetic and capable of attracting another person even without the performer’s intention. The impresario’s suspicions of betrayal may not be misplaced because in scene 7 “Night Comes”—perhaps the most unexpected in the play—the wife visits the artist’s cage, unlocks it, and bares her breasts in an attempt to feed the starving artist, in what could be construed as the desire to connect with the artist’s ascetic purity in addition to an act of mercy. However, not only does he turn his lips away but the butcher-guards, who had pretended to be asleep, burst into laughter and shame her. As it irks the impresario, attracts and moves his wife, or incites the butchers to a tighter surveillance day and night, Ernest’s hungering provokes strong emotions and is shown to be a powerful actor with tangible consequences for its presentation on the stage.

The eve of the concluding ceremony creates an opportunity for several other dialogic exchanges, where even the minor characters are given a voice: among them, the two girls tasked to help the emaciated artist to his meal express doubts about his fasting, tempt him with some nourishing nuts, even tease him, and yet leave him unfazed. Then, the apprehensive impresario engages in a sustained persuasive act to avoid surprises: to ensure that Ernest will exit the cage and eat, evidently not a given, he tries to convince him to be more social like his competitors; he contends that now people “even prefer false hunger artists, because they are more human, more like them” (103), whereas his artist is a loner, alienated, who will end up looking boring and ridiculous. Despite Ernest’s lack of interest in his peers, the impresario is the one who must worry about enrolling fresh audiences every day while facing the interference of other actor-networks (hunger artists or types of spectacle) that may impede his ability to sell the show.

In fact, worried about the small audience on day thirty-nine, he pays someone to provoke a scuffle and generate free publicity. This scene underscores the material necessities of show business and the dwindling enthusiasm for the performance of hunger itself at a transitional point when it would need to be attached to another “number,” and therefore extend its network, to yield an acceptable income. In this case, the static performance of fasting is supplemented with another, a fabrication that disguises a theatrical frame as a primary framework.[16] When, by the end, the hunger artist releases all of his network’s associations, he looks almost out of history, dressed in his unfashionable, white-striped dark suit, with lips painted dark blue and greasy shiny hair. Raising his hands, he asks to be allowed to depart, confesses his fasting as the height of arrogance, promises not to disturb everyone else’s well-earned digestion, and leaves. Thus, the play concludes without venturing into the genre’s period of decadence at the circus, eliminating the practical need to put a panther on stage in a rather realistic type of play.

In sum, Różewicz strives to illuminate the material context of a hunger artist’s performance by developing original dramatic dialogues involving several human agents around him and alerting the audience of the existence of other performers competing to enroll the very same type of spectators. In this way, we become more intensely aware of the vulnerability of the complex social assemblage necessary to make such a performance sustainable: once enough people decide to dissociate themselves from the hunger artist’s network, hunger as spectacle must cease.

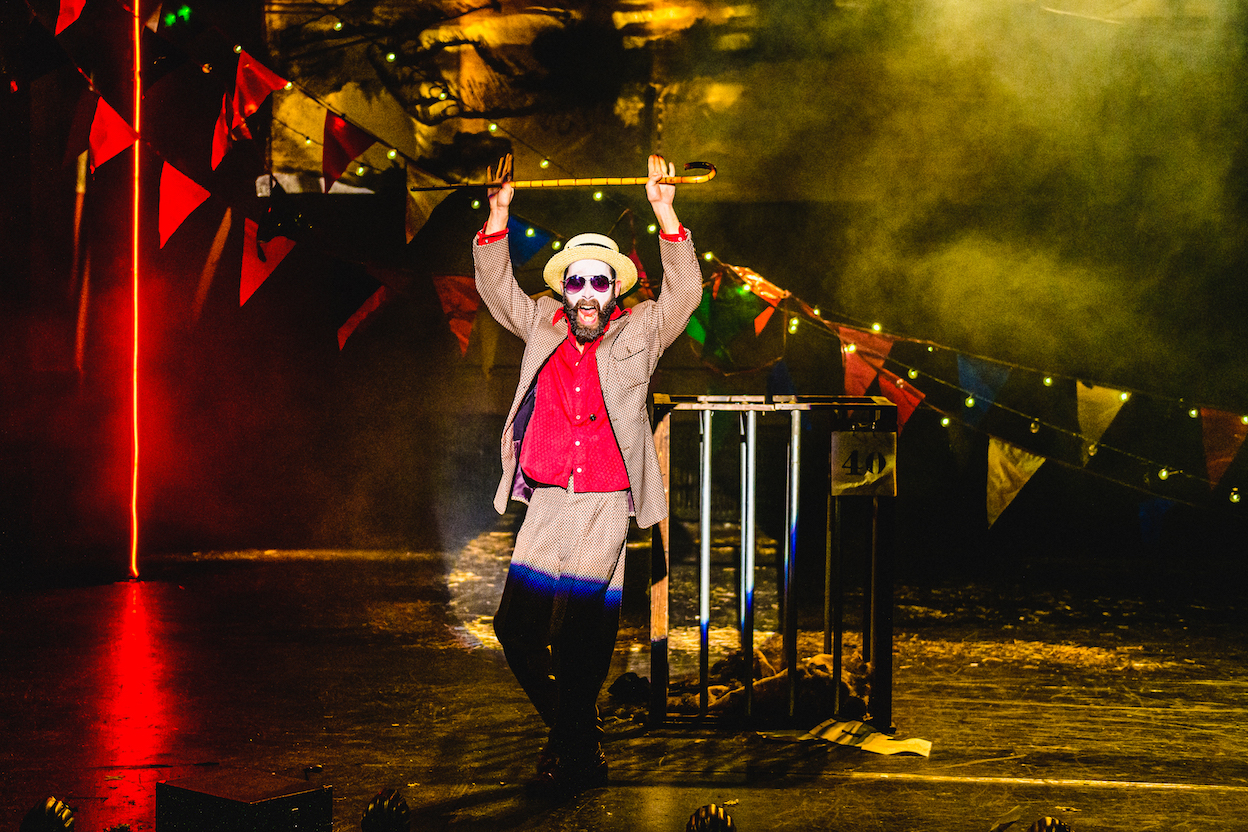

In counterpoint to Różewicz’s writerly approach, Sinking Ship’s A Hunger Artist stays much closer to the short story’s text but develops its theatricality by employing a single player for multiple characters, several performing objects, and even audience members as helpers. The production is a collaboration between performer Jonathan Levin, playwright Josh Luxenberg, and director Joshua William Gelb, who all worked on the dramaturgy. The show premiered in 2017 at the Off-Off-Broadway Connelly Theatre in New York City, received the Summerhall Lustrum Award for excellence at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in the same year, and is still in repertory at this time.

The first major innovation by Sinking Ship is that the beginning third of the show is recounted not by the invisible omniscient narrator but by the impresario himself. Wearing a sizable fat-suit (a detail absent from the short story[17]), Levin as the impresario enters carrying a large cage on a cart, places it center stage, and—while eating an apple—pulls a battered framed poster out of the trunk, which advertises “The REAL Hunger Artist!” Speaking to the audience in an Eastern European accent meant to convey his Jewishness,[18] unlike Różewicz’s often unpleasant character, he is rather witty and affable although resigned to the current decline in the “business of hungering.” He proves that recession by literally counting all the spectators one by one, multiplying the ticket price, and lamenting that the resulting total is lower than the cost of renting the theatre itself. Thus, even though in the past there used to be a real orchestra of eighty, he is now left with just an old Victrola record player, the non-human actor left to subsume all the musicians’ agencies (and avoid paying their salaries).

The impresario then demonstrates the typical hunger artist performance by climbing behind a toy theatre, operating tiny stick puppets from above, and giving voice to each character, from the hunger artist to his own younger self with more hair, to the butchers, doctors, and two ladies.[19] Demonstrations are yet another way of framing primary reality as “performances of a tasklike activity out of its usual functional context in order to allow someone who is not the performer to obtain a close picture of the doing of the activity” (Goffman 66). But, in this case, the viewing distance is not ideal: after coaxing a spectator to admit that—although he can get a sense of the performance from his seat—the toy theatre is definitely too small for detail, the first theatre-within-the-theatre version is followed by a more interactive reenactment.

At this point, Levin widens the frame of “play” to encompass real people when he calls upon the spectators to embody the roles he just demonstrated and convinces a few of them to enroll in the fictional hunger artist’s network and step onto the stage.[20] One audience member cast as impresario on the spot is asked to slowly read a long introductory piece, which allows Levin to shed his fat-suit behind a wing and immediately enter the cage as the hunger artist himself. The doctor-spectators are then furnished with a doctor’s bag, asked to open the cage, and take actual measurements of the artist, in a scene that gives them only vague audio instructions on how to perform each task, followed by more specific ones when they inevitably and comically fail. After the final toast, this second version ends with the audience members returning the tools and props, and to their seats. Through this reenactment of the closing ceremony, the spectators who remained in their seats have thus watched, all in one place, a varied set of agencies that include not only the major human actors involved in co-creating the frame around the performance of hunger but also the non-human tools that both discipline and measure it.[21] Conceptually, they have witnessed how an actor-network can grow by activating more numerous associations (the enrolled audience members) and how it shrinks again once associations are no longer needed. In this case, the assemblage is always different because the spectators who can be turned into temporary performers vary with each show.

After this more interactive moment, Sinking Ship adds an original third segment, an increasingly fast-paced repetitive routine in which Levin changes city of performance so frequently—catching a train, setting up the cage, ripping off the sheets with the number of fasting days, eagerly eating some near-liquid oatmeal from a bowl—that it becomes apparent that the hunger artist and the impresario are (almost) the same person, both participants of the same assemblage, two faces of the same coin, in cooperation with a host of non-human agents that punctuate and collaborate to the act of fasting for spectacle. As I mentioned earlier, Latour points out that the full complement of actors involved in interactions is often mysterious, because they do not appear in the same place at the same time, or are not simultaneously visible.[22] This sequence in particular seems to me the most strikingly ingenious because it reveals in synthetic (isotopic, synchronic, synoptic) fashion, with means only available to performance, the artist’s crucial interconnectedness with the impresario and the larger network of cities and things that enable fasting to work as theatre. It also shows a novel side of the hunger artist who, despite his thinness, is here quite nimble, able to jump up and down the cage, stretch, and athletically run from place to place, not quite a feeble individual risking death by starvation but rather a consummate artist of deception, in this case not bothered by any shadow of regret as in the other works seen above. Coincidentally, this is the only one of the three artistic renditions seen here to translate the historical hunger artists’ shows of physical prowess as a demonstration of their resilience despite the fasting.

The following segment then inventively deploys assemblages between the human performer and non-human ones, also a way for Levin to multiply the characters he can play at the same time. In one virtuoso scene, he manages three at once—the hunger artist, the impresario, and the circus manager—by inserting his arms into the sleeves of two coats hung on their respective stands; with only his head left unencumbered, he ends up signing the circus contract by holding a pen in his mouth. Then, after embodying the circus manager as the ringmaster rousing the crowd for a pigmy hippopotamus nearby (and not the expected artist’s cage), a super-quick costume change brings back Levin as the hunger artist, who embarks on his longest fast until day ninety-eight. Because the performer himself is left to rip off the sheets from the pad that counts the days, the interaction proposes a more dynamic human/non-human collaboration than Kafka had envisioned. Just like the clock in the short story, the pad is a figuration of the same non-human agent, time, a crucial antagonist here because its passing increases hunger. But whereas in Kafka’s recounted performance the clock sat as a rather transparent intermediary, in this production the pad operates more as an active mediator: for example, when the number goes from fifty-three straight to sixty-two, folding nine days into an instant, one could already argue for the pad’s material agency as a switch that triggers the subsequent abrupt change of lights and near-collapse of the performer’s body, weakened by the assumed fasting in the interim. Moreover, by combining the action of the human performer with the pad’s synthetic semiotics, Sinking Ship is able to tangibly show time as an active agent with an impact on the performance and, through its compression, to represent hunger and its effects more vividly on stage.

In yet another change, quickly back after a blackout, Levin is dressed as circus manager and finds a puppet of the withered hunger artist. Once again multiplying his concurrent roles aided by a performing object, he voices the dialogue between the two, until the artist dies and is removed from the cage. The puppet allows the scene’s pathos to remain theatrically convincing, even in the context of an otherwise more light-hearted production, but what is more noteworthy is that by letting the spectators watch the very last phase of “morbid inanition”—as Dr. Luciani would have called it—this production manages to show a scene that was never before presented on stage, not by the historical hunger artists (for obvious reasons) nor by Różewicz. Eventually, the last scene dispenses with human presence altogether when a toy panther is placed on the rotating Victrola record player while a portable lamp projects the blown-up shadow of the cage’s new occupant onto the backdrop. If Kafka’s short story illustrated a post-anthropocentric shift by foregrounding the animal energy of a living panther versus the human’s consumption, this final action in Sinking Ship’s production derives all its dynamism exclusively from the “vibrant matter” (Bennett) of non-human objects.

Overall, Sinking Ship injected uniquely performative elements into the short story material, exploring a broad variety of theatrical expressive means: first, the virtuoso solo performer enacted multiple characters through changes in body, costume, accent, and props; second, certain characters were shown in several versions, such as the impresario who appeared first embodied by Levin, then by an audience member, then again as a toy theatre figurine, a coat stand, and eventually a disembodied voice from the Victrola record; third, Sinking Ship included the real audience in the performance frame, with all the adjustments required by the unpredictability of spectator-actors as they join a particular evening show’s network; finally, all sorts of non-human actors became crucial co-protagonists. The sense that the show was indeed able to make hunger perform was perhaps best captured by Time Out New York’s reviewer Helen Shaw who concluded: “The artist starves, but we leave sated.”

In light of these case studies, going back to the question of how deliberate fasting can be visibly performed, we have seen that hunger artists, as opposed to living skeletons, engaged not only in a display of extreme thinness but also in an exhibition of their skills, namely the ability to endure food deprivation, withstand physical weakness, and even defy death for as long as possible. This extended but often uneventful spectacle could be interspersed with other actions to pass the time, such as reading newspapers, conversing with their watchers, or telling stories (Mitchell 244). Other larger scale interactions like Succi’s collaboration with physiologists or his fencing demonstration were all aspects of a multi-pronged strategy to cultivate the audience’s gaze, so essential to frame hunger as spectacle. When a venue like the Berlin restaurant placed a hunger artist in the midst of regular customers intent on consuming their succulent dinner, the setting itself made them spectators and amplified the drama of fasting for real.

Some of these historical approaches, filtered through Kafka’s selection, were then incorporated by Różewicz and Sinking Ship into a fictional frame for the traditional stage, with the additional requirement of a much more concentrated performance time. On the one hand, the Polish author’s dramatization expanded Kafka’s set of characters and their dialogic exchanges to convey the society of human actors the hunger artist performed for and depended on; on the other hand, Sinking Ship made use of every trick in the book of theatricality to deliver a virtuoso performance infused with the additional agency of both non-human performing objects and real audience members.

More specifically, an option for materializing hunger on stage is simply talking about it in public: a performer can become a storyteller and recount someone else’s act, just like Sinking Ship’s impresario with his toy theatre, or the profession’s actions can be described in dialogues with other characters as seen in Różewicz. Spectators could also deduce an artist’s fasting from the matter-of-fact visual contrast with others who are either very fat or eat plentifully; this disparity could be imbued with other values, pitting the artist’s asceticism and saintly aura against the crassness of other people gorging themselves, as in the episodes with the impresario’s wife or the butchers. Furthermore, hunger can be seen to act when the fasting triggers emotional responses and other types of reactions in others, or instead when we are made to realize its role as a cog of a larger mechanism for producing money and food for others. Alternatively, the collaboration with specific objects like those employed by Sinking Ship can become an index of the fasting, such as the feverish way Levin eats from the bowl after his character’s lengthy abstinence, the business with the tear-off pad, or the interaction with the withered puppet.

Remarkably, compared to other actors that may seem to act on their own, precisely because hunger tends to be invisible, presenting it on stage offers a clearer demonstration that no actor-network performs alone but, instead, always implies some relationality.

[1] Of course, intentional fasting does not necessarily entail a spectacular component, as in the case of religious ascetism or hunger strikes as protest. See, for example, Walter Vandereycken and Ron van Deth’s From Fasting Saints to Anorexic Girls: The History of Self-Starvation, still an essential volume on deliberate starvation although limited to the Western/Christian context.

[2] See https://www.sinkingshipproductions.com/a-hunger-artist, accessed May 1, 2024. I thank Jonathan Levin and Josh Luxenberg for providing me with the photos for this article and a video recording of the 2020 staging at the Connelly Theatre in New York City, which lasted approximately 80 minutes.

[3] To avoid confusion between the ANT notion of “actor” as agent and its common use in theatre, I always employ “performer” in the latter sense. A performer can be an actor/agent as well, but of course not all actors/agents perform on stage. Others have contributed to a large body of work on ANT, such as Michel Callon or John Law: for a comprehensive analysis of how ANT and assemblage theories can be deployed in theatre and performance studies, see my recent monograph Actor-Network Dramaturgies: The Argentines of Paris.

[4] As I synthetized elsewhere, actor-networks are never stable but in a constant movement that drops certain associations while carrying others forward: “‘sociology of translation’ best captures the active movement of transformation implied by associations as they become channels for the displacement of materials […] in an intricate network of competing actor-networks. Ultimately, without translation there would be no actor-networks” (Boselli 7). Here I always use the term “translation” in the ANT sense of movement along the network’s pathways.

[5] The “disciplined self” is of course a reference to Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison.

[6] Hunger artists were “almost without exception males” (Vandereycken and van Deth 76). For the phenomenon of “fasting women” and how their abstinence from food could be construed as performance although it took place in their own homes, see Gooldin 27–38.

[7] The article quotes from “Succi: The Fasting Man,” The Lancet, March 10, 1888, 478, emphasis added.

[8] As Maud Ellmann noted, “it is impossible to live by hunger unless we can be seen or represented as doing so. Once the public disappears the artistic performance becomes a simple pathology” (17).

[9] Here the author quotes Anonymous, Cenni Biografici 7–8.

[10] Luciani saw three main phases of human “inanition,” i.e., the exhaustion caused by lack of nourishment: “first, a brief period (3–4 days) of intense pain and feeling of hunger; second, a long period (20–25 days) of physiological inanition, in which vital constants remained quite stable and finally, a crisis of morbid inanition, which led to death” (Nieto-Galan 73). Succi reached his record of forty-five days in New York in 1890 (Mitchell 242).

[11] Breon Mitchell believes that this kind of interaction would have been unlikely for the historical hunger artists like Tanner or Succi and appears more like a “blurring of the distinction between the well-orchestrated ‘performance’ of a famous hunger artist and the shameless exhibition of a freak,” i.e., a living skeleton (248).

[12] John Law, for example, underscores that “crucial to the new material semiotics is performativity” (12).

[13] This two-decade practice is a biographical detail added by Różewicz.

[14] See for instance the recent volume by Peter Rader.

[15] In ANT terms, “An actor […] becomes stronger to the extent that he or she can firmly associate a large number of elements—and, of course, dissociate as speedily as possible elements enrolled by other actors. Strength thus resides in the power to break off and to bind together” (Callon and Latour 292).

[16] Goffman defines a fabrication as “the intentional effort of one or more individuals to manage activity so that a party of one or more others will be induced to have a false belief about what it is that is going on” (83).

[17] The members of Sinking Ship were unaware of Różewicz’s play. Interview with Jonathan Levin, Josh Luxenberg, and Joshua William Gelb, May 29, 2022.

[18] A reference to Kafka himself, but the whole creative team is also Jewish. Interview with Jonathan Levin, Josh Luxenberg, and Joshua William Gelb, May 29, 2022. In this case, Kafka, the man, can thus be seen as an agent in the impresario’s characterization.

[19] All these props and performing objects, from the apple to the Victrola player to the toy theatre, are creative additions by Sinking Ship.

[20] In ANT terms, an actor gradually increases its size through constantly enrolling other actors, i.e., translating them into its sphere of influence, and becoming their spokesman. See, for instance, Callon and Latour’s “Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: How Actors Macro-Structure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them to Do So.”

[21] Of course, Sinking Ship’s voice instructions further shape the action at the level of the second lamination of the frame.

[22] “First, no interaction is what could be called isotopic. What is acting at the same moment in any place is coming from many other places, many distant materials, and many faraway actors. […] Second, no interaction is synchronic. […] Third, interactions are not synoptic. Very few of the participants in a given course of action are simultaneously visible at any given point” (Latour 200–01).

Anonymous. Cenni Biografici. Giovanni Succi. Esploratore d’Africa. Già delegato della ‘Società di Commercio coll’Africa’ di Milano e membro della ‘Società psicologica di Madrid.’ Tipografia Economica, 1897.

Bennett, Jane. Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things. Duke University Press, 2010. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv111jh6w

Boselli, Stefano. Actor-Network Dramaturgies: The Argentines of Paris. Palgrave Macmillan, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-32523-6

Bouman, P. J. Revolutie der Eenzamen: Spiegel van een Tijdperk, 34th ed. Van Gorcum, 1954.

Callon, Michel. “Some Elements of a Sociology of Translation: Domestication of the Scallops and the Fishermen of St Brieuc Bay.” The Science Studies Reader, edited by Mario Biagioli, Routledge, 1999, pp. 67–83.

Callon, Michel, and Bruno Latour. “Unscrewing the Big Leviathan: How Actors Macro-Structure Reality and How Sociologists Help Them To Do So.” Advances in Social Theory and Methodology: Toward an Integration of Micro and Macro-Sociologies, edited by K. Knorr-Cetina and A. V. Cicourel, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1981, pp. 277–303.

Cozzi, Enzo. “Hunger and the Future of Performance.” Performance Research: A Journal of the Performing Arts, vol. 4, no. 1, 1999, pp. 121–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.1999.10871652

Ellmann, Maud. The Hunger Artists. Starving, Writing, and Imprisonment. Harvard University Press, 1993. https://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674331082

Foucault, Michel. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Translated by Alan Sheridan. Vintage Books, 1995.

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree. Translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky. University of Nebraska Press, 1997.

Goffman, Erving. Frame Analysis: An Essay on the Organization of Experience. Northeastern University Press, 1986.

Gooldin, Sigal. “Fasting Women, Living Skeletons and Hunger Artists: Spectacles of Body and Miracles at the Turn of a Century.” Body and Society, vol. 9, no. 2, 2003, pp. 27–53. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X030092002

Hutcheon, Linda, with Siobhan O’Flynn. A Theory of Adaptation, 2nd ed. Routledge, 2013.

Kafka, Franz. “A Hunger Artist.” Selected Short Stories of Franz Kafka, translated by Willa and Edwin Muir, The Modern Library, 1952, pp. 188–201

Lange-Kirchheim, Astrid. “Das fotografierte Hungern: Neues Material zu Franz Kafkas Erzählung ‘Ein Hungerkünstler.’” Hofmannsthal Jahrbuch zur Europäischen Moderne, vol. 17, 2009, pp. 7–56. https://doi.org/10.5771/9783968216935-7

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network Theory. Oxford University Press, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199256044.001.0001

Laera, Margherita. “Introduction: Return, Rewrite, Repeat: The Theatricality of Adaptation.” Theatre and Adaptation: Return, Rewrite, Repeat, edited by Margherita Laera. Bloomsbury, 2014, pp. 1–17. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781472526533

Law, John. “Actor Network Theory and Material Semiotics,” 25 April 2007, http://www.heterogeneities.net/publications/Law2007ANTandMaterialSemiotics.pdf, accessed May 1, 2024.

Mitchell, Breon. “Kafka and the Hunger Artists.” Kafka and the Contemporary Critical Performance: Centenary Readings, edited by Alan Udoff, Indiana University Press, 1987, pp. 236–55.

Moody, Alys. The Art of Hunger: Aesthetic Autonomy and the Afterlives of Modernism. Oxford University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198828891.001.0001

Nieto-Galan, Agustí. “Mr Giovanni Succi Meets Dr Luigi Luciani in Florence: Hunger Artists and Experimental Physiology in the Late Nineteenth Century.” Social History of Medicine, vol. 28, no. 1, 2014, pp. 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1093/shm/hku036

Rader, Peter. Playing to the Gods: Sarah Bernhardt, Eleonora Duse, and the Rivalry That Changed Acting Forever. Simon & Schuster, 2019.

Różewicz, Tadeusz. The Hunger Artist Departs. Mariage Blanc and The Hunger Artist Departs: Two Plays by Tadeusz Różewicz. Translated by Adam Czerniawski, New York, Marion Boyars, 1983, pp. 71–109.

Shaw, Helen. A Hunger Artist (review). Time Out, December 10, 2019. https://www.timeout.com/newyork/theater/a-hunger-artist. accessed May 1, 2024.

Vandereycken, Walter, and Ron van Deth. From Fasting Saints to Anorexic Girls: The History of Self-Starvation. New York University Press, 1994.