You will be familiar with this plot, which “makes visible, yet again, what is already there: the ghosts, the images, the stereotypes” (Taylor 28). The “scenario of discovery” is described by Diana Taylor as a meaning-making paradigm that combines both the archive and the repertoire. In the context of this article, the archive consists in an accumulation of information about plants in an urban, riverfront park as gleaned through a walking tour. The repertoire that I describe consists in the performances, gestures, expressions, movements, and behaviours of participants during this event. In this paper, I re-enact a well-rehearsed scenario in which a group of well-meaning white people go out in search of plants to document and learn their culinary and medicinal uses. Taylor explains that the scenario “structures our understanding,” while allowing for occlusions. “[B]y positioning our perspective, it promotes certain views while helping to disappear others,” she writes (28). The botanical tour that I describe reiterates the imperial botanical mission, in which explorers set out to discover and inventory a wealth of plant resources, excising these without acknowledgment of the colonial-capitalist relational context to which they belong.

On the other hand, the scenario allows us to “recognize the areas of resistance and tension” (30), making way for “reversal, parody and change” (31) and allowing for “many possible endings” (28). The embodied repertoire developed through the nature walk that I recount is ambivalent in its outcomes. While attuning participants toward biodiversity in a “human disturbed environment” (Tsing), teaching us to love the products of our own devastation, the colonial-capitalist systems responsible for perpetuating this violence remain unnamed. As such, the social actor and their role as participant in such a tour are called into question. Chris Bell argues that: “Noticing relations helps us walk toward an ethics of artistic responsibility founded on the connectivity of social, historical, and ecological relations” (188), calling this a “living land acknowledgment.” Becoming attuned to place involves a sensory (aesthetic) entrainment, but this must go beyond the personal to socio-political action. Above all, settler-scholars like me are being called upon to tread with humility and care in learning to become “naturalized to a place,” as Robin Wall Kimmerer (214) puts it.

Margaret Atwood writes that weeds are for the “meek in needs / They are not for the rich” (74). Foraging, or harvesting wild plants and fungi for consumption, has been central to Canadian settler cuisine since the first arrival of colonizers in the fifteenth century. Foraged plants were eaten by early missionaries, explorers, surveyors, wilderness writers, naturalists, pioneers, and filmmakers. Many Canadian cookbooks featuring wild plants like dandelions and nettle have appropriated traditional knowledge from First Nations without permission or acknowledgement (see Makoons Genuisz). Hunger and even starvation have often been the motivations for learning to identify, reap, and use wild plants.

Weeds are vital components of cuisine for many people who cannot afford organic, non-GMO, local produce. Furthermore, Melissa Poe et al. show that the reasons for foraging, gathering, harvesting, and gleaning are far more diverse than food security. Significantly, these activities also fulfill food and health justice and food sovereignty. My own experience with foragers, fishers, and hunters corroborates their findings that “Localizing food production can be seen as an alternative response to neoliberal and colonialist food economies that have created socially and environmentally costly externalities” (“Urban Forest Justice and the Rights to Wild Foods" 411; see also Alkon and Mares; Emery et al.; Guthman; McMichael).

To pretend as though Canadian cuisine is only or primarily what we find in farmers’ markets and (high-end) restaurants is to seriously misrepresent the reality for most eaters in this country. Many people cannot afford to visit the establishments that frequently appear in TV shows and in publications about Canadian national cuisine. So, what do people eat in everyday life? Through more than thirty free food-art tours that I have organized in and around Tiohtià:ke/Mooniyang/Montréal, I have met many people who engage in what could be considered fringe food practices like foraging, dumpster-diving, shopping in food co-ops, and participating in community cooking groups. These are both voluntary, aesthetic activities and also motivated by need.

In 2020–2021 there was a sharp rise in dependence on food banks not only in Canada but around the world. Food policy researcher Valerie Tarasuk reports that in 2021, 15.9% of households across the country were food insecure. This includes First Nations people living on reserves and people experiencing homelessness. Keeping in mind that these figures are probably underestimates, the report shows that in Canada nearly 1.4 million children, or one in six, are living in food insecurity, defined as “inadequate or insecure access to food due to financial constraints” (“Household food insecurity in Canada” 7). In one of the richest countries in the world, one in nearly every six households worries about not having enough food, relies on low-cost foods, cannot afford balanced meals, skips meals, does not have enough to eat, and often goes without food for whole days. In Nunavut, 78.7% of the population is food insecure. These figures represent the highest food insecurity ever recorded in this country (Tarasuk. Food Insecurity in Canada- Latest Data from PROOF). Eating wild plants is one alternative to an unhealthy and inaccessible food system that is failing us all.

Importantly, though, foraging requires skill and aesthetic accomplishment to hone perception. The hunger that catalyses foraging contains within it deep interest in other species, and demands attunement to place, and foragers develop sensory skills through which they become intimately emplaced in their local environments. Their actions serve human needs, but also those of other species. The experiences of Poe et al. are similar to what I have witnessed in what is now called Verdun, a borough of Montréal, Canada.

[F]oragers indicated that plants and mushrooms drew them in, bringing foragers closer to the ecologies of their neighborhoods; and these more-than-human beings were in turn embraced within the social and communicative worlds of foragers. Listening to plants and mushrooms was a common practice: to assess the being’s desire and purpose; to seek signs of whether it wanted to be harvested; and to determine sustainable limits (“Urban foraging and the relational ecologies of belonging” 912).

Foragers honour these “vital materialities” that are most often cast aside, overlooked, or treated as trash except as a last resort.[1] This aesthetic sometimes also involves an orientation toward food justice. “Informal practices of collecting help to understand not only survival strategy to alleviate hunger but also tactics to circumvent regulations that frame urban gathering as undesirable,” according to Flaminia Paddeu (2). The desire that drives foraging is my interest here.

There are rules involved in foraging, and performative dimensions to its enactment that lead to a particular orientation toward place. I have noticed a certain choreography involved in foraging by paying attention to the bodily habits that it calls forth. In the waterfront walk, Balade Nature, which I describe below, participants are guided through a tour of edible and medicinal plants. They can be found crouching, stooping, leaning, observing, listening, comparing, moving back and forth, even lighting the scene—as with cell phones—for a better view, discussing and exchanging information, looking down, treading carefully, digging with bare fingers, picking, and more. These acts attune participants to place. While the Balade Nature was not framed as a performance or an artwork, it did consist in aesthetic training, so there is benefit in analyzing it from a performance angle.

Furthermore, walking, an act that is central to foraging, is also a well-developed methodology in artistic practice that is pertinent in the fields of fine arts and performance. Urban foraging can perhaps be considered a kind of counter-aesthetics that asserts a “right to the city,” as David Harvey (2012) would have it, or a “right to collect,” in the words of Paddeu (2). The exclusive, elitist etiquette associated with high-end cuisine is challenged by the counter-aesthetics of this choreography of foraging, which belongs to what Michel de Certeau would have called a “practice of everyday life”. In the context of climate catastrophe, which involves widespread biodiversity loss and the rampant spread of “invasive weeds” on the shores of Kaniatarowanenneh where I walk, it can even be considered a choreography of the essential, opposed to the aesthetics of excess expressed in fine dining.

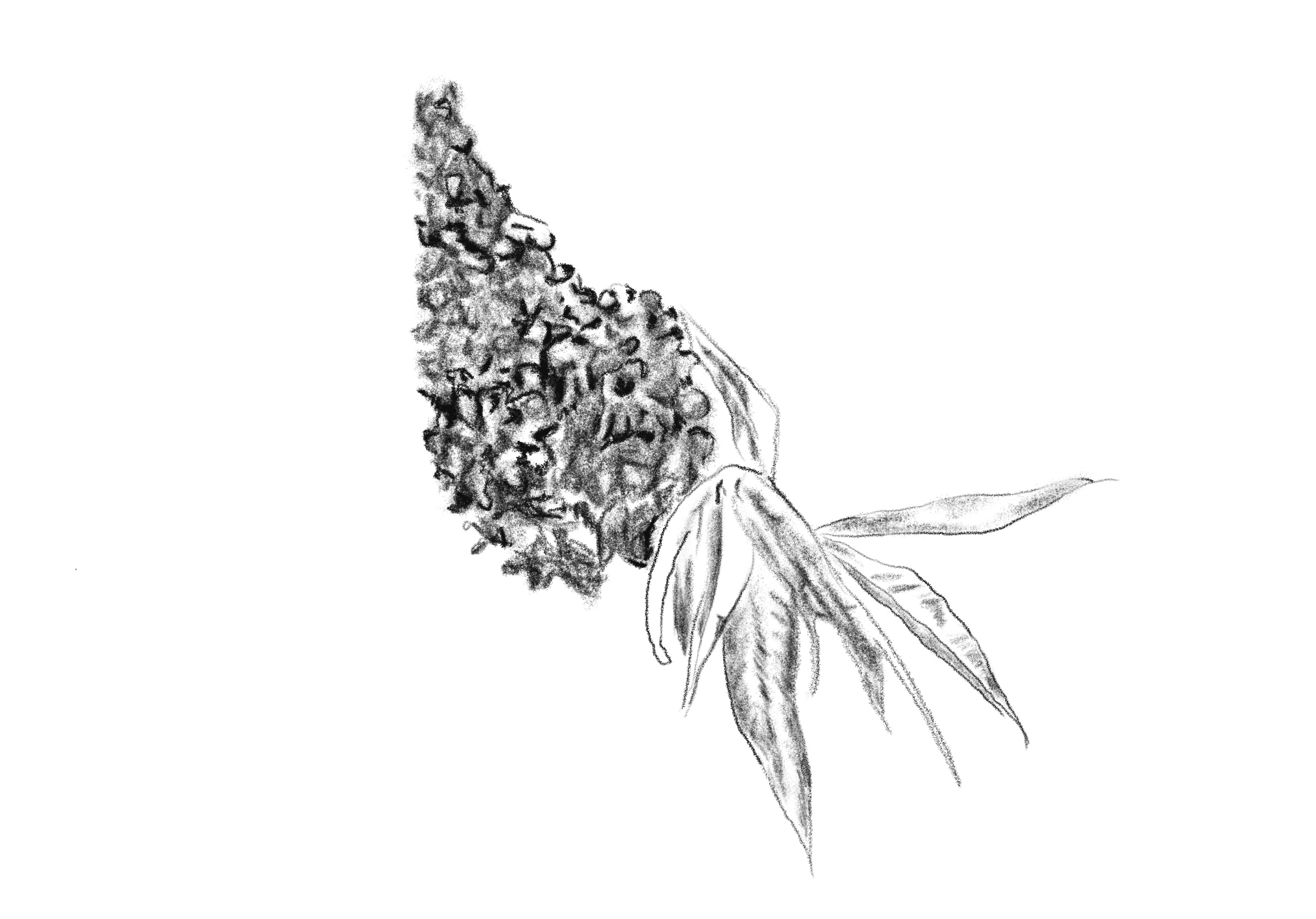

Throughout these pages, I sprinkle botanical drawings alongside textual descriptions of plants. Why do I do this? What purpose do these hand drawings serve? I interpret colours in tones, entering into the curves and crevices of each petal, leaf, and stem with precise gestures. My eye and my fingers follow the contours of every shadow, every texture, and every turn. Through this act of drawing, which requires close looking, the bodies of plants are recorded in my memory, archived in my gestures. I make decisions with every mark about how to interpret the vicissitudes of these bodies—the shadows cast by their tissue, the highlights and falloff of the sun cast over their surfaces. These drawings aim to record with detail and accuracy, but they are also fragmentary. I have taken artistic license.

The practice of botanical drawing was established by European polymaths who travelled on the ships of explorers. Alexander von Humboldt, so the story goes, escaped his German mother’s clutches to travel throughout the Americas, producing renditions of wide-ranging flora and fauna in his multi-volume treatise Kosmos. His work went on to form the basis of modern ecological science. Men like him, or Sydney Parkinson or Joseph Banks, who both accompanied Captain Cook on his travels, gathered up the natural world in their sketchbooks. It wasn’t impossible for women to become famous for archiving the world’s plant heritage either. Marianne North was a botanical illustrator in Victorian times and travelled the globe documenting exotic species and eventually exhibiting them in a gallery that she founded at the famous Kew Gardens, a spectacular display of cultural imperialism.

Drawing is a form of collecting. It requires intense observation of what is at hand. In botanical illustration the artist is at pains to reproduce with fidelity what they are witnessing, with the objective of archiving an image of this other being for safeguarding in galleries, books, and other collections, ostensibly placing the world’s heritage in safe keeping. Botanical illustrations are meant to be faithful records of the diverse plant life that exists in various regions of the globe. Taylor points out though, that heritage is etymologically linked to “inheritance,” underlining “material property that passes down to the heirs” (23). Western artists and scholars have for too long assumed themselves to be heirs to plant collections. This notion of plant life as property, or a material resource for humans, is a myth that needs to be contested.

At the root of colonization were plants. The first European explorers went out in search of spices.[2] In the collections of botanical illustrators who travelled with imperial expeditions, we recognize a hunger for complete knowledge. As with culinary craving, there is a desire for mastery through intellectual dominance and skill. While aiming to capture, however, drawing does not presume to record what was there with disinterest. As a medium for documenting the natural world, it is partial; it apprehends an encounter while leaving holes. Drawing is by its very nature fragmentary, flawed, and very interested. It is bubbling over with desire, a magnetic pull driving the artist (whether the drawer considers themselves to be such or not) to their subject, compelling them to sit, entranced, gaze fixed and seemingly motionless for immeasurable periods. Perhaps it is time to return this probing gaze inward.

What can our hunger for weeds teach us (foragers, botanical illustrators) about ourselves? When I draw a plant, it is because I am trying to memorize it. I am trying to register its image in my mind. I am attempting to record its features so as to recognize its family members in future encounters. To achieve this, the plant in question must in some way become part of me. In many cases, the plants that we consume regularly are the ones that we recognize. It is by incorporating these others again and again, visually, through touch, and through the mouth and digestive system, that they become familiar. Ask virtually anyone to draw you a carrot and it will quickly become apparent that this vegetable has been so thoroughly grasped through the senses that it is fairly easy to produce a recognizable rendition on command. The carrot is part of us.

Is it possible to turn artistic practice toward the cultivation of reciprocal relations, as opposed to exploitation? In her book, Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer urges her students and her readers to share their gifts with plants, to cultivate reciprocity. Drawing involves many stages of both loss and gain. It is always at least in part a testament to the impossibility of complete capture. We cannot harvest it all, like it or not. Importantly though, in drawing, the effort of recording is evident. It does not try to hide itself. The artist’s hand is always evident. It is me you see. I bare myself, flawed, on the page, humble witness to this incomprehensible life I have beheld. I have enjoyed these plants while leaving what I encountered behind, intact, for others, and for each plant itself too. I am learning ways to satisfy my hunger without completely devouring those from whom I learn. I am learning how to share what I have received. “In learning reciprocity,” says Kimmerer, “the hands can lead the heart” (240). Have I adequately compensated the plants for what they have given me?

Activities aimed at training the senses—foraging, nature walks, and drawing, for instance—help to cultivate care for wild plants, and far more. There are widely practised, unwritten rules amongst foragers that demonstrate care for fellow pickers, but also for other species, and for the land. For example, a widespread practice amongst foragers is to pick only what you need, never more. The purpose of this rule is to leave enough for others while ensuring further propagation of the plant. In addition, foragers are usually careful to cut stems, not pull, since pulling could result in damaging or killing the plants. Another widely practiced rule is to leave things clean—either in the condition in which they were found or improved. These are values that are shared with urban scavengers or dumpster divers as well. “To prevent the loss of access to prime locations,” explain Russell Vinegar et al., “divers espoused basic dumpster diving etiquette, unwritten, but common to all participants. This included keeping the area clean (‘leave no trace’), staying quiet at dumpsters neighbouring private residences, and practicing variations of ‘take only what you can use or distribute’” (249). These efforts toward improved conditions take into consideration more-than-only-human well-being. One forager I met used the example of nettle: to avoid letting the plant go to seed, foragers perform a beneficial action in cutting down the plant. In nettle patches on the waterfront, there is evidence of foragers’ maintenance activities.

Foraging is a communal affair. It is tied to culinary practices passed down intergenerationally and shared within communities. Recent studies on foraging, gleaning, and urban scavenging show that these values persist. For instance, Flaminia Paddeu notes: “Despite fundamentally varied profiles, some gestures, values, and representations are shared by gatherers. Cooperation, gift giving, and social reciprocity are common among various types of gatherers, including homeless people as well as student communities” (3). In these communities, knowledge and skills are shared across the ages too. “[F]oraging is an intergenerational and traditional practice,” note Melissa Poe et al. (“Urban Forest Justice and the Rights to Wild Foods”, 413). Central to its efficacy is an understanding of plants’ roles within local ecosystems, and of their place within social rituals. Community medicine and cuisine have both been historically connected to healing and mutual well-being.

The area now called Verdun has been radically transformed over the past 125 years, for instance through the reduction of the Kahnawà:ke reserve and the obliteration of fish spawning grounds to make way for colonial-capitalist expansion. Through many walks alongside Kaniatarowanenneh, “the big waterway,” otherwise known as the St. Lawrence River, I have learned about some of the plants that grow unbidden there. Many of them have culinary or medicinal benefits for humans. By walking the waterfront with people who are interested in these plants, it has become clear to me that the preoccupations described above remain central. Learning from plant medicine can be one way to distribute knowledge collectively instead of allowing health care and food systems to be centralized and controlled by those in power.

La Maison de l’environnement de Verdun (MEV), managed by Nature-Action Québec, is mandated by the borough to guide citizens and organizations towards better environmental practices. MEV has a mission to promote biodiversity along the nearly 14km of Kaniatarowanenneh shoreline in the neighbourhood of Verdun. One of their programs has urban park rangers roaming these shores to monitor plant diversity and to educate residents about its value. In August 2017 I participated in Balade Nature, a tour of this waterfront led by horticulturist and consultant in urban agriculture Natachat Danis and biologist Eugénie Potvin of MEV. Over the course of two hours one warm evening, they led a group of about twenty participants from plant to plant along the shoreline, discussing the medicinal, culinary, and aesthetic attributes of each. These plants feed fish, birds, and insects. As humans learn about their virtues, their appetites are piqued too. It seems to me that the hunger that motivates trends in urban foraging is not only gustatory, but more broadly sensual. On one hand, this craving for “exotic species,” such as the nine-foot stands of Phragmites australis that line the shores, seems motivated by colonial desire. How can this plant serve me? In what ways can I consume it? Yet surely cultivating appreciation for others can also be mutually beneficial, instead of exploitative. According to Potawatomi teachings, says Kimmerer, “If we use a plant respectfully it will stay with us and flourish. If we ignore it, it will go away. If you don’t give it respect it will leave us” (157). In nourishing themselves, respectful foragers engage in reciprocal relations that ensure the longevity of plants too.

In what ways do plants feed bodies? Many of the plants that I have learned about through urban tours are edible for humans. But the Balade Nature challenged participants to consider the ways in which wild plants also nourish other species, the land, the water, and the entire ecosystem. Although this walk was not presented as an artwork, its main objective was to transform the perception of participants, cultivating an aesthetic appreciation for the park’s plants. I noticed that the tour encouraged certain bodily practices that facilitated attunement to other species. We were guided into a rhythm of walking, stopping, leaning in, observing, touching, smelling, and taking our time, repeating this process as we moved slowly from plant to plant. Through this rhythmic movement, we were invited to commune with nature.

The importance of communing, corresponding, and communicating with plants is of increasing interest across disciplines. Matthew Hall brings evidence to bear from his field of botanical science: “Claims of a constructed human-nature separation have to acknowledge that within scientific circles, since the publication of Darwin’s Origin of Species, humans and plants have been recognized as sharing a common (if distant) ancestor” (137). The studies he cites show that plants are capable of: initiating movement; sensation; perceiving their environments; perceiving light (which is a kind of seeing); behavioural intelligence; basic decision-making; problem-solving; reasoning; intention and choice; communication within and beyond the individual (between the various parts of its own body and with other plants, microbes, insects, animals, etc.); recognition of self/nonself; and modifying their environments (see also Gagliano et al.).

In light of these findings, Hall suggests that we develop dialogical relationships with plants. We can do this by developing forms of inter-species communication that allow for the very different “voices” of all beings to be “heard.” Plants communicate in myriad ways, as food scholar Joseph Pitawanakwat from Wikwemikong First Nation charismatically explains (2020). According to him, plants communicate through their uniqueness. In his teaching on medicinal plants, he urges people to look closely at the shape and structure of leaves, which are often mirrored by human body organs. One example he offers is sweet fern, which resembles human intestines. In this view, the human body is a reflection of other earthly creations. “Listen to plants, to their stories,” he says, encouraging people to learn how to look at plants to uncover their messages. In this way of thinking, plants are not subordinate to humans, but kin.

Our guides encouraged us to examine the many ways in which we might commune with plants on the waterfront in Verdun, in addition to eating them. Consuming wild plants can have a number of consequences, including but not limited to: allergic reaction; poisoning; wanted or unwanted propagation (of seeds); death (of one’s own body or extinction of other species, who can’t survive without adequate supplies of certain plants); disappointment; disgust; fines; hallucination; transfixion; euphoria; exaltation; delight. Meanwhile, applying plants medicinally can produce results ranging from rashes to a youthful glow. Communing with nature is an ambivalent pursuit and our own ingestion is not the only consideration of interest. Consumption begins long before the moment when a foreign body meets the tongue.

Cultural imperialism is enacted through the language that we use, too. As others have articulated, we need to develop new languages if we wish to foster better relations with other species and with the world more largely. Kimmerer describes this as “learning the grammar of animacy” (48ff). In most Indigenous languages, she explains,

we use the same words to address the living world as we do for our family, because they are our family. To whom does our language extend the grammar of animacy? Naturally, plants and animals are animate. But […] what it means to be animate diverges from the list of attributes of living beings we all learned in Biology 101. In Potawatomi 101, rocks are animate, as are mountains and water and fire and places—beings that are imbued with spirit, are sacred medicines, our songs, drums, and even stories are all animate. (55–56)

Understanding the entire world as animate, vibrant, and alive, makes it difficult to sustain definitions of Canadian cuisine that essentially consist of a compilation of dishes, served up as an inventory of national tastes.

The need for an entirely new language to talk about ecosystems is addressed too by Robert MacFarlane in his book Underland: A Deep Time Journey, where he writes about mycelium—the city of fungi beneath our feet—and other mysterious realms that evade human perception. “We need to speak in spores,” he suggests, to avoid converting the world “into our own use values” (44:50). How to speak a language of multi-species flourishing? How to invent modes of communication that do not plunder? This is no easy feat in the academy, but it is up to artists and scholars to do the work. What Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing calls “the arts of noticing” can be cultivated to turn our attention to forms of thriving outside of avaricious capitalism. “Many preindustrial livelihoods,” she writes, “from foraging to stealing, persist today, and new ones […] emerge, but we neglect them because they are not a part of progress” (22). Donna Haraway uses the term “worlding” to describe the worlds that are brought into being through processes of symbiotic becoming that exceed species boundaries. Independence is a (liberal) myth, according to this proposal, in which fungi and plants are examples of “companion species” that thrive (or not) together. In this process: “natures, cultures, subjects and objects do not pre-exist their intertwined worldings” (13). What is being expressed by all of these authors is the pressing need to overturn the dominant colonial-capitalist paradigm in favour of models that emphasize cooperation, collaboration, and mutualism. We cannot continue to envision ourselves as discrete individuals if we want to go on.

The Balade Nature presented by MEV was designed to introduce participants to the main players along the riverbank, with a special focus on plants of culinary and medicinal interest. We stop first at humble weeds bearing white flowers. Danis explains that there are many clovers that look alike, belonging to the same family. Some are edible and others not. White clover should be set aside, she warns. Red clover, on the other hand, is interesting. It cleanses the blood. My own communion with the plants that we encountered that evening has unfolded far beyond that two-hour walk. It is a mediated communion that has involved reviewing and spending time with photo and video documentation of the plants that I made during the Balade Nature and on many other visits to that place.

In the group’s discussion of clover, complex relations are negotiated. Family members are cast to one side or the other. Teioneratoken,[3] or red clover, is an interesting plant, we are told. Containing chemicals called phytoestrogens, it can regulate hormonal balance for women, and is used in supplements marketed for women’s health. It has also long been used as a source of calcium and magnesium. The flower or the leaves can be used to create infusions. Danis explains that it creates a bit of a milky effect that makes it a refreshing addition to cereals. It is a plant that is very well known in English pharmacopeia and is considered to be sacred. According to Danis, it can be worn as an amulet around the neck for protection. This is attractive from an aesthetic point of view, too. Danis’ pharmacological instruction is consistently enhanced through aesthetic advice on how to use the plants for beautification within the home or in the wardrobe. In the mouth and on the body, the sensory attributes of these plants are underscored.

Danis considers the plant from a more-than-only-human perspective as well. Though it may not immediately recall lentils and chickpeas, clover is in the family of legumes. It fixes nitrogen in the soil, thus playing an important ecosystemic role. Nevertheless, as we examine several other species, participants’ questions revolve around how each one can be turned to human ends, for consuming as food or for visual pleasure. Our guides gladly share these tips, while also returning to broader ecological concerns. To arrive at these ecological issues, we are guided along a very narrow footpath, squeezed between common reeds that give the impression of bushwhacking through a jungle. Burrs cling to pants and socks and exposed bits of skin emerge stinging from brushes with nettle or wild parsnip. In the safety of this group tour, many participants find themselves following a route onto which they would never otherwise venture. This is urban wilderness—just there beside the asphalted walking and bicycle paths, but invisible to most passersby. Our guides introduce a whole new world, hidden in plain sight. It closes in on us from every side.

We move to a plant with long, curly, heart-shaped leaves. Orhohte’ko:wa, or burdock is used as a root vegetable in Japanese cooking (where it is called gobo), often served sautéed. Ideally, says Danis, it should be harvested in the autumn. The roots should be rinsed right away to remove dirt and dried to avoid the production of mould. After that they can be grated, and added to soup. Like chicory, which is plentiful here too, the roots can be used as a coffee substitute. Burdock (where the burrs come from) also has antioxidant, skin-soothing properties that are valued for treating signs of aging, acne, dermatitis, psoriasis, and eczema. It is infused in skincare products that exploit its antioxidants and essential minerals. These include magnesium, manganese, calcium, zinc, selenium, and iron. Burdock seeds are treasure troves too. They can be infused in whisky for several weeks and used to treat the skin.

Knowing about the plants that settle in a particular place instills a deeper sense of connection for me. My attraction toward the intersection of taste and place has led me again and again to lowly weeds. And here are more. The Spotted Touch-Me-Not is less ominously known as Jewelweed. This annual grows in bottomland soils, in ditches and along creeks. Like most others to which I am drawn by various guides, they grow in unloved places. This one can be used to treat poison ivy. It can be eaten parsimoniously but is mainly used in medicinal applications. What is this sense of connection I feel? Does awareness of how this plant can serve me lead to a sense of empowerment? Do I feel armed by knowing what can do me harm? Is my impression of self-competence fed by acquiring practical knowledge? Or do I feel a deeper sense of relationality by attending to these plants?

Emerging from the dense vegetation into an area that has been groomed by the municipality to allow for sitting on scattered flat stones, Potvin intervenes to widen our view to the landscape. “Why is the riparian buffer important?”, she asks. “Why should we care?” In answer to her own question, she outlines three ecological functions of the vegetated area along the river. Its first benefit is that it absorbs the water, providing a barrier in times of high rainfall runoff. This prevents pollutants from entering the river. This is important for all creatures who are dependent on that water. Its second function is as an ecotone, a transition area between two biological communities. Here it is a meeting place for two ecosystems, one aquatic and the other terrestrial. This is a liminal space, crucial for species like frogs and aquatic plants, who need both ecosystems. Finally, the riparian buffer prevents erosion. Even if I had joined the tour to learn how to make a truly local meal, I am learning about the reciprocity of species too—how each depends on the other.

Ambling along, the evening slipping fugitively away as the group becomes tangled in conversation, we stop to talk about the Tara:kwi, or staghorn sumac, that adorn the footpath. We spread out enough to make way for the bicycles that whiz by on the adjacent asphalt path. Danis entices the group by commenting that the berries make a nice, tart drink that resembles lemonade (some call it sumacade). Like many other plants, however, it is potentially toxic. The fruits contain tannic acid and should not be excessively boiled. If prepared correctly, though, sumac is an antioxidant, a diuretic and is antifungal. It can be applied both internally and externally. Many people plant sumac ornamentally, since it looks like an “exotic” tree, with fine, sharp-toothed, lance-shaped leaves and stunning, cone-shaped, blood-coloured fruits. It is easy to find recipes online for sumacade. Danis recommends drying the berries (quickly, so they don’t become moldy) to eliminate insects and dirt. A fine powder can be made from this, and it serves as a popular spice in Middle Eastern cuisine. Danis also recommends a sumac-infused vinegar. The fruit has astringent properties and a bitter flavour. Its deep red hue is a rich source for dyes as well. Bringing us back again to less anthropocentric concerns, Potvin explains that sumac (vinaigrier in French) plays an important role in retaining the soil and sediments. Our attention zooms in and out, from shrub to leaf to flower to berry to landscape, and back. Out to the water. Down to the compact earth below our feet. Above to the tropical canopy enveloping us. We pivot and perceive in 360 degrees.

From there we move to sumac’s neighbour, another plant of variable appreciation that is often dubbed a “weed”: Kanon’tíneken’s,[4] Asclepias syriaca, or common milkweed. Potvin describes the importance of milkweed for monarchs: these butterflies can only lay their eggs on milkweed leaves. Monarchs migrate over very long trajectories from Canada to Mexico and are currently in decline. There are many projects underway to promote milkweed planting in support of monarch populations. Monarch caterpillars can only feed on milkweed, so this species is dependent on the plant throughout its life cycle. These are more-than-only-human concerns. A keystone species, the thriving of monarchs is also directly connected to human health (Smith et al.). If we wish to protect our own food sources, milkweed must be protected for monarchs.

Milkweed pods contain latex, which protects the plant from predators. The pods can be eaten, but with great caution to avoid sickness and potentially even death, particularly for people with latex allergies. Preparation for cooking involves a repetitive boiling process in salted water as a first step. More often though, the plant is used externally to treat wounds. In the landscape, milkweed is an indicator of compact soil that is not well-drained. In mid to late summer the plant produces large round umbels—pink flowers arranged in a luscious, spherical shape. This is attractive to many species. While we pause here, many participants rejoice in the scent of this clonal perennial forb. In Québec, certain microbreweries make IPA-style beers from local hops, with milkweed providing a nice flavour to such brews. It aids digestion and has a relaxing effect too. What’s more, it is a galactagogue, promoting milk production in women. Because it encourages estrogen though, it can be dangerous for certain hormonal conditions.

We are standing in a field that must be at least forty by thirty feet. It is filled with milkweed plants. This site is unlike anything I have ever seen. Potvin says that she recently spotted a rare “bleu d’Europe”—a blue butterfly from Europe, first spotted in 2007 near Mirabel Airport Northwest of Montréal. This is one of thirteen sites where the borough had stopped mowing the lawn, allowing a wide variety of plants to find their place. According to Potvin, this re-naturalization program has seen mixed support. There is still a lack of appreciation for urban biodiversity, which to some appears unkempt. Historically, says Potvin, grass was seen as chic—to have the luxury of unused land that nevertheless demanded intense (underpaid) manual labour was a demonstration of wealth. There is an ethic to Potvin’s aesthetic training, which moves us to perceive in new ways.

The sun is beginning to set as we descend toward the riverbank. There we encounter burdock again, and a discussion emerges about whether it could or should be eaten from this place. Potvin explains that the park area where we are located, between the river and the walking path that borders Boulevard LaSalle, is human-made, and constructed from backfill. The city discourages eating what grows in public areas, and she suggests that these precautions are a good idea, since the land is likely contaminated. This is significant especially when considering eating roots, which absorb whatever the earth contains. One alternative could be to collect seeds to plant at home, she offers. Some participants declare a contrarian interest in consuming the leaves and flowers of edible plants that grow in the park, despite (or perhaps in spite of) potential health concerns.

The sky streaked with orange and hot pink, we move on, making our way toward the final stop, at the garden of Thérèse Romer, who lives here beside the river. “What happens when we stop mowing the lawn?” asks Romer upon our arrival. This distinguished lady is advanced in age and it seems she has no time to spare for introductions. To answer her question, we need flashlights to scan the ground. Several smartphones are promptly produced, and we illuminate the area before her, what she calls “le préfleuri.” This un-mowed bit of land was “re-naturalized” by the sole will of Romer. Fed up with the city’s beautification program, she cordoned off a space that would be set aside for grasses and wildflowers—whatever happened to take root. She offers us wild carrot seeds from one of the interlopers. Otherwise known as Queen Anne’s Lace,[5] this biennial plant can be harvested in the second year after planting. It is the ancestor to domestic carrots. Romer explains that carrots came from Europe with the colonizers, who brought so many things, wittingly and not. Before dismissing the group, she impresses upon us the importance of visiting the préfleuri at every moment—morning, noon, and night, in every season. To know this little place, it must be visited often. One must spend the time. And this is where we stop, she says. It is late.

Did the events described above meet the goal set out by MEV to increase appreciation for the varied forms of life that thrive along Verdun’s waterfront? Through discussion of plants’ contributions—to insects, to humans, to their ecosystem—participants were meant to be appreciative, which can also mean being grateful, beholden, indebted, or obliged. Did we, as participants in the tour, properly commune with our plant neighbours? Did this tour satisfy our hunger for gastronomic knowledge of local plants? Was this hunger troubled by the tour, and by Potvin’s subtle insistence that the nutritional needs of other species, and the functioning of the ecosystem should be prioritized over our own culinary curiosities?

There were moments in the Balade Nature when participants invited plants into their bodies. Breathing in the fragrant perfume of milkweed, many participants expressed appreciation for its fine, pervasive odour. Encountering sumac, people of all ages reached for the plant, petting fuzzy flowers with index fingers. Pores exchanged with plant tissues. Animal and plant engaged in sending and receiving, in exclamation or wordlessly. Participants took seeds from the guerrilla garden of Thérèse Romer. It may be presumed that some of these seeds found their way to domestic gardens, and that (wild?) carrots may have been consumed as a result of this initial encounter on the waterfront that night. If so, it could be said that human-carrot communion was initiated in the préfleuri on the event of that walk by the water.

In what ways did the bodies of untended plants mingle with human bodies? In what ways were each transformed by these unions? Observing, touching, tasting, naming—these acts lean toward domestication but can also be approached with reverence, and a respect for distance. Crucial to the re-naturalized sites along Verdun’s waterfront is a commitment to leaving them be. A principal of non-interference allows for the agency of plants and of other species to govern in those places.

Italo Calvino writes about the paradoxical desire to know an other through eating, which ultimately threatens to destroy the object of affection. He explores this theme through the terrible yearning between a man and wife to achieve complete consummation. His exploration of this violence within an intimate relationship, “chaste yet infinitely carnal,” is echoed on the social scale by using tourism as a framework within which to expose colonial exploitation. As the couple travels through Oaxaca, Mexico, conflicting cuisines are combined by the hands of white and brown women. When Olivia, the wife, asks their tour guide what became of the body parts of sacrificial humans in the time of the Aztecs, he evades by saying that the vultures were responsible for delivering them to the gods. She presses, but he resists the European tourist’s insistence on devouring the secrets of his ancestors.

Perfect resonance can only be achieved through annihilation of the other. Chilies “opened vistas of a flaming ecstasy,” says the narrator (Calvino 7). A reciprocal and complete communication between he and his wife is an act of assimilation, achieved through a process of ingestion and digestion: “a terrible harmony, flaming, incandescent” (20). The husband calls this the “universal cannibalism that […] erases the lines between our bodies and sopa de frijoles, huachinango a la veracruzana, and enchiladas” (29).

During the Balade Nature, conversation often turned to questions about what species can and can’t be eaten by us—tourists, citizens, settlers, humans. We discussed methods of preparing milkweed as food, for example. But we also talked about the urgent ecological needs of this plant. Implied in these discussions is the notion that human hunger, desire, and curiosity are sometimes in conflict with the needs of other species. Participants motivated by an initial interest in learning about how plants can serve their own needs—as medicine, food, and decoration—were challenged to reflect more widely on the ecosystems to which they belong. Why not eat wild, urban plants? Because it is illegal, we learned. Because they grow from toxic soil. Knowing this, what responsibilities do we hold in caring for this land? Thinking of food as relations instead of as products impels us to care. Practising foraging, and participating in foraging tours and nature walks, are activities that can cultivate a sense of response-ability. These activities can help to develop relations with plants, by training perception toward their unique traits.

What does it mean for a white settler artist-scholar to promote environmental attunement on unceded Indigenous land? This big question is part of an even bigger one, about how I can live responsibly in a place where I was born as a trespasser. The hungry colonizers who arrived at least five hundred years ago survived by the grace of Indigenous guides and hosts who taught them how to trap, hunt, fish, forage, prepare, and eat local animals and plants. Over time, these have been appropriated and treated as discrete resources with economic equivalencies. In her book, Our Knowledge is not Primitive, Wendy Makoons Geniusz shows how Indigenous botanical knowledge was appropriated by colonists, who, understanding only in part what they were taking, apportioned it piecemeal. For Indigenous people, she explains, “colonization was not just economic and physical exploitation and subjugation. It was also the exploitation and subjugation of our knowledge, our minds, and our very beings” (2). Trying to cultivate reciprocal relations is a fraught and ambiguous process for me. The question of how to do this while avoiding further colonization is not straightforward.

As Indigenous scholars such as Leanne Betasamosake Simpson and Taiaiake Alfred have underscored, dispossession has been at the heart of settler colonialism and continues to create opportunities for neoliberal expansion. The claims that I make in this paper are modest and I do not pretend that the activities I describe are working toward restorative justice for Indigenous people. However, I do believe that the sensory skills entailed in foraging work to “destabilize the pervasive mythology of colonialism (and its aesthetics)” (Martineau and Ritskes 3). Cultivating relations is key to this. Simpson points out that “within Nishnaabeg thought, the opposite of dispossession is not possession, it is deep, reciprocal, consensual attachment.” She explains, “Indigenous bodies relate to land through connection—generative, affirmative, complex, overlapping, and nonlinear relationship” (43). For non-Indigenous people living in this place, it is an ethical challenge to contest dispossession by nurturing reciprocal relations. This is precisely what Kimmerer encourages settlers to do. For her, to “become native, to make a home” means to live “as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it” (9). Learning to recognize and appreciate the diversity of fellow species where I live represents a steep learning curve that is also crucial to this process of making a home.

I strive to make land acknowledgment the core of my artistic practice and my writing. Chris Bell defines land acknowledgment through “performance as a mode of inquiry that enables pathways to critique the contours of dominant structures restricting and supporting life as it is known” (187). For Bell, as for me, emplaced research hinges on “deepening our understanding of relations through embodied explorations” (188). The twofold approach to this practice as he describes it involves both “noticing relations (personal)” and “complicating relations (systemic)” (189). The development of sensory skills that I have described is essential to creating conditions for radical infrastructural change. Apprehending urban weeds with respect, as life-sustaining beings, is a political stance that opposes the colonization of plants, and therefore of land. This means a rejection of industrial food systems that homogenize plant species, eliminating genetic diversity and sterilizing entire ecosystems with fertilizers and pesticides. I consider urban foraging to be a “practice of care and affect that directly challenge[s] the infrastructures that monitor and restrict the ability to create futures and sustain worlds that are multiple, plural [and] heterogeneous” (Prado De O. Martins 54).

There is a sad irony in conducting this work on stolen First Nations land. The actual earth on which we walked during the Balade Nature was extracted to construct Montréal’s metro system during the spectacular Expo ’67, a display of national pride. The park that we walked through is an invasion of Kaniatarowanenneh, which has interfered with the hunting and fishing rights of the Kanien'kehá:ka and other nations. I am venturing into fraught and contested terrain. My attempts to cultivate relations through this paper do not lead toward a conclusion. My writing, and my drawing, and my visits with the land are rather invitations for response.

The author would like to thank the Fonds de recherche du Québec—Société et culture for support with projects (2022-CCZ-299729) and (2018-B5-205121). Thanks also to la Maison de l’environnement de Verdun, especially Eugénie Potvin, and to Natachat Danis, for their generous participation in this research. I am also deeply grateful to the blind peer reviewers, and for the caring editorial guidance from all editors in this joint GPS-PSi publication.

[1] Vital materialism is a term from feminist new materialism, especially attributed to Jane Bennett, to acknowledge that all matter is alive, even that which appears to be inert. Here we can consider weeds to be vital matter, for example.

[2] Pablo Vargas, of the Royal Botanical Gardens in Madrid, notes that most people have a misconception about the primary objective of 16th century expeditions of Columbus and Magellan, which aimed to find a new trade route to India and its spices, not silver or gold. Columbus died believing that he was in India and that he had discovered new spices. Clove was literally worth its weight in gold at the time.

[3] This and most of the other Kanien'kéha plant names I have used in this paper are from Aionkwatakari:teke, Kahnawà:ke’s Health and Wellness newsletter from October 2017 (Communications Services of Kahnawà:ke Shakotiia’takehnhas Community Services 2017).

[4] See episode 4 of the Youtube series Onkwanonhkwa, where hosts Ranikonhriio Lazare and Katsenhaiénton Lazare of the Kanien’kehá:ka nation teach about Kanon’tíneken’s, Common milkweed (Lazare and Lazare).

[5] I don’t know of a word for this plant in Kanien’kéha.

[6] In The Marvelous Clouds, John Durham Peters urges readers to acknowledge: “the splendid otherness of all creatures that share our world without bemoaning our impotence to tap their interiority. The task is to recognize the creature’s otherness, not to make it over in one’s own likeness and image. The ideal of communication, as Adorno said, would be a condition in which the only thing that survives the disgraceful fact of our mutual difference is the delight that difference makes possible” (31).

Alfred, Taiaiake. “On Reconciliation and Resurgence.” Rooted, vol. 22, no. 1, 2022, pp. 76–81. https://taiaiake.net/2022/09/25/on-reconciliation-and-resurgence/

Alkon, Alison Hope, and Teresa Marie Mares. "Food sovereignty in US Food Movements: Radical Visions and Neoliberal Constraints." Agriculture and Human Values 29 (2012): 347-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-012-9356-z

Atwood, Margaret. The Year of the Flood. Vintage Canada, 2010.

Balade Nature. Visite des espaces naturels de Verdun, led by Natachat Danis, Eugénie Potvin and Jean-François Caron and hosted by Maison de l’environnement de Verdun, August 30, 2017.

Bell, Chris. “Prompts for Acknowledging Relations.” Theatre Topics, vol. 31, no. 2, 2021, pp. 187–193. https://doi.org/10.1353/tt.2021.0035

Calvino, Italo. Under the Jaguar Sun. 1982. Translated by William Weaver, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1988.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. 1980. Translated by Steven Rendall, University of California Press, 1988.

Communications Services of Kahnawà:ke Shakotiia’takehnhas Community Services. Aionkwatakari:teke 22(5), October 2017. https://www.kscs.ca/service/aionkwatakariteke

Emery, Marla, Suzanne Martin, and Alison Dyke. “Wild Harvests from Scottish Woodlands: Social, Cultural and Economic Values of Contemporary Non-Timber Forest Products.” UK Forestry Commission, 2006.

Gagliano, Monica, et al., editors. The Language of Plants: Science, Philosophy, Literature. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Guthman, Julie. “Neoliberalism and the Making of Food Politics in California.” Geoforum, vol. 39, no. 3, 2008, pp. 1171–1183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2006.09.002

Hall, Matthew. Plants As Persons: A Philosophical Botany. State University of New York, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781438434308

Haraway, Donna J. Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11cw25q

Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso, 2012.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teachings of Plants, Penguin UK, 2020.

Lazare, Ranikonhriio, and Katsenhaiénton Lazare. “Onkwanónhkwa Episode 4: Common Milkweed / Kanon’tíneken’s.” 21 August 2019. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sKej2RIfG1w

MacFarlane, Robert. Underland: A Deep Time Journey. Penguin Audio, 2019. www.audible.ca

Makoons Genuisz, Wendy. Our Knowledge Is Not Primitive: Decolonizing botanical Anishinaabe teachings. Syracuse University Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1353/book.109810

Martineau, Jarrett, and Eric Ritskes. “Fugitive Indigeneity: Reclaiming the Terrain of Decolonial Struggle Through Indigenous Art.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 3, no. 1, 2014, pp. i-xii..

McMichael, Philip. "A Food Regime Analysis of the ‘World Food Crisis’." Agriculture and Human Values, vol. 26, 2009, pp. 281-295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9218-5

Paddeu, Flaminia. “Waste, Weeds, and Wild Food.” EchoGéo, vol. 47, 2019 https://doi.org/10.4000/echogeo.16623

Peters, John Durham. The Marvelous Clouds: Toward a Philosophy of Elemental Media. University of Chicago Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226253978.001.0001

Pitawanakwat, Joseph. “MIIJIM: Food as Relations—Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee Food Systems”. Finding Flowers, 10 November 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4Z1EtA91g0

Poe, Melissa R., et al. “Urban Forest Justice and the Rights to Wild Foods, Medicines, and Materials in the City.” Human Ecology vol. 41, 2013, pp. 409–422. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-013-9572-1

Poe, Melissa R., et al. “Urban Foraging and the Relational Ecologies of Belonging.” Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 15, no. 8, 2014, pp. 901–919. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.908232

Prado de O. Martins, Luiza, “There Are Words and Worlds That Are Truthful and True.” In The Eternal Network: The Ends and Becomings of Network Culture, edited by Kristoffer Gansing and Inga Luchs, Institute of Network Cultures and transmediale e.V, 2020.

Simpson, Leanne Betasamosake. As We Have Always Done: Indigenous Freedom Through Radical Resistance, University of Minnesota Press, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1pwt77c

Smith, Matthew R., et al. “Pollinator Deficits, Food Consumption, and Consequences for Human Health: A Modeling Study.” Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 130, no. 12, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1289/EHP10947

Tarasuk, Valerie. Food Insecurity in Canada- Latest Data from PROOF [webinar]. PROOF, March 26, 2020. https://proof.utoronto.ca/resource/food-insecurity-in-canada-latest-data-from-proof/

Tarasuk, Valerie, Tim Li, and Andrée-Anne Fafard St-Germain. Household Food Insecurity in Canada, 2021. PROOF, 2022. https://proof.utoronto.ca/resource/household-food-insecurity-in-canada-2021/

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas, Duke University Press, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385318

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Thriving in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton University Press, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400873548

Vargas, Pablo. “The Value of Nature,” in the Around Nature Discussion Series, moderated by Diana Ayton Shenker and presented by Juanli Carrión with the Cultural Office of the Spanish Embassy in collaboration with Cultural Programs of the National Academy of Sciences, 14 May 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HzaGGKr_qps

Vinegar, Russell, et al. “More Than a Response to Food Insecurity: Demographics and Social Networks of Urban Dumpster Divers.” In Local Environment, vol. 21, no. 2, 2014, pp. 241–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.943708