.pagerNavigation {

display: none !important;

}

Mezur, Katherine. “Parade, Pilgrimage, Passage: Walking on Water from Rijeka to Aomori.” Global Performance Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.33303/gpsv1n1a10

Mezur, Katherine. “Parade, Pilgrimage, Passage: Walking on Water from Rijeka to Aomori.” Global Performance Studies, vol. 1, no. 1, 2017, https://doi.org/10.33303/gpsv1n1a10

Parade, Pilgrimage, Passage: Walking on Water From Rijeka to Aomori

Katherine Mezur

University of California Berkeley

How does a specific place define itself? Especially a lesser-known place, a non-capital place, a place of the sea, a place that can step out of time? Rijeka, Croatia, and Aomori, and Mt Osore, Tohoku Japan are those kinds of places. They are not defined by only geography but the actions of the humans on and with that geography over time. This essay is about how these places performed in interaction with the PSi participants. While the theme of the Fluid States’ year of localized gatherings was “performances of unknowing,” the places we encountered were their own performances of deep knowing, like storage places of history, beliefs, families, economies, war, disasters, and loss. Woven into every texture of local geography, which includes its industry, religions, governments, climate, and all of its inhabitants, there is a deep sense of belonging to this place. There exists a genealogy of the interactions of the landscape and people, a geochronic “dwelling perspective” (Ingold 2011 188), which we, the PSi curators and participants, were invited to enter and activate.

This is a story, a narrative of places, marked by their geography between the land and the sea. Each place shares the instability of being land surrounded by or near the sea, and the enduring stability of this fraught relationship.

Rijeka is a Croatian port city where buildings sweep up from the sea to mountainous areas. There are famous castles and churches in the hills, bells toll regularly, and the city buildings, homes, and stores are largely pale stucco and elegant, mixed with the 70s concrete and postwar, and roads are cobblestone or partially stone and pavement. Everything looks towards the sea.

The coastal land is inhabited by large container shipping cranes, which arc over the water like giant Trojan horses. There are old factories on the water that are empty, or abandoned, waiting, yet they stand hugely present near the shore. Water is the other half of Rijeka. Its Kvarna bay lies in its curving rugged Adriatic coastline, and this is cut by a stone jetty or breakwater that cuts into the bay creating a protected arbor.

This long breakwater was the staging ground for PSi Fluid States’ “organizational” performance event, which mapped the journey of the year-long chain of events, which became the 2015 places and states of unknowing. Here is where the walking on water journey began. The plan was to introduce each fluid state event place’s special focus through some kind of interactive performance that could be accommodated on the breakwater with its paved road and a high stone wall, and take advantage of the incredible space between the land and the open water.

PSi Fluid States released its members to contemplate and participate in these local places, these crevices of culture, these non-scripted interactions between visitors and citizens and place. PSi and other similar organizations most often must set up a meeting-driven theme, a willing institution, and then make sure that the place, theme, and system of conferencing is inclusive and broadly defined in order to include a wide range of people and their contributions. While this works, very often the conference’s place and local populations become “neutralized” or even erased in the high concentration of diverse events. Ironically, this inclusive internationalization can homogenize our differences. Fluid States, from its inception, opened the flood gates, and asked us to dig into a particular fluid state, to focus on a singular geography, to concentrate on specific inhabitants and their performances, and to generate an event that would propel our performative research further than we could imagine. These local “performances of unknowing” were to arise from deep knowing and became the multiple driving forces of Fluid States events.

In this essay I will describe several “moving” events that were the outcomes of the dare to perform the unknowing through radical concentration on a specific fluid state. Each of these events was based on local place and populations but mixed strangers, visitors, and locals into encounters with the unknown. I am not suggesting that these events could only happen in the year of PSi Fluid States, but I don’t think PSi members, or the local populations, would have experimented in these kinds of physical immersive experiences with the local without the conditions of the Fluid States’ focused place/event mandate. Further, these events shared the attributes that all Fluid states sites depended on: local collaboration and stranger/inhabitant ensemble production.

This is a critical travelogue that passes between states and places and performance events on the Rijeka, Croatia Breakwater, the PSi Tohoku pilgrimage event to Osore-zan (Mt. Osore), and the vessel performance passage “rite” of “Pacific Passages” between the fluid states of the Cook Islands and the Tohoku region functioned as performances of knowing and making places. This is about a parade, a pilgrimage, and a passage across oceans and coasts, through immersive choreographies invested in the deep seated placeness of geography and its inhabitants in time: Geochronic performative events.

I highlight particularly pleasurable and unexpected events, along with reading the crisscrossing journeys with Said’s often stated orientalist turn and Homi Bhabha’s densely packed “other”-ing. The way is studded with stops, on purpose to make the voyage look back upon itself. I also use different forms of writing to match the photo album effect: description, provocations, theories, saturated melodramatic impressions, and verse. Diverse writing opens up the view to the panoramic.

BREAK:

Tim Ingold, in his The Perception of the Environment, writes about two themes in his concern for the environment:

First, human life is a process that involves the passage of time. Secondly, life-process is also the process of formation of the landscapes in which people have lived….a focus on the temporality of the landscape … might enable us to move beyond the sterile opposition between the naturalistic view of the landscape as a neutral, external backdrop to human activities, and the culturalistic view that every landscape is a particular cognitive or symbolic ordering of space. I argue that we should adopt …a ‘dwelling perspective,’ according to which the landscape is constituted as an enduring record of – and testimony to – the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it, and in so doing, have left there something of themselves. (Ingold 189)

In all three cases, Rijeka’s breakwater, Mt. Osore’s temples, stone paths, and lake, and Aomori Museum’s dark berm embankments and white walls and hallways, participants experienced this dwelling perspective. The place, the landscape (of building, water, or land) became performative: we acted in-dwelling. We enacted the geochronic dwelling in the place.

The sections of this essay should be transparent and overlap so that the one story can be read through the other. The photographs could be in parallel positions and stream across each other as fluid events in order to get a sense of their choreographic walking on water. I wish to emphasize how the local place is singularly different but the shared local geographies of paths, water, stones, and “special sites,” which are situated between land and sea, form the shared fluid states of place. Landscape, spirituality, and corporeality meet and digress through a pilgrimage of gestural vocabularies of walking. This is a parade, a pilgrimage, a passage. The overall performance of each creates a dissonant geochronic dance. In this “here” we are “with” the landscape, moving.

Parade: DREAMLAND or ZOOMING on the Breakwater

In Rijeka, on its signature breakwater, we became a serial event, a long parade of participants, waiting, watching, and doing at each fluid states site. We shared the problem that we had films and projections to share, but these filmic events could only be seen in flickers because of the long sunlit evening on the breakwater.

First, we listened, because Santorini was going to be a listening site, a Greek island full of planetary rumbling. We listed to a radio commercial for perfume. It was a tale of irony and capitalism.

Then we saw a dance that would never be danced: our Lebanon fluid state became too difficult after Rijeka, but here the dance flashed blue and gold between the water and the sun.

We played games with the Philippines’ fluid states group. We ran, jumped, pushed, shoved, and blew on our bright green whistles. Who won?

Rijeka’s breakwater is a solitary wall and walkway, concrete over old giant stones.

We walked in slow motion, in unison with the butoh dancer creating a long parade in the slow sunset. Unison movement enforces a visual and kinaesthetic unity, walking slowly in patterns forward and backward and slow seeing at the waters’ edge. We moved together. We came to the wall of butoh, where only a ghost light of the dance figures could be seen on the rocky wall. BUT, Hayato Kosuge called out to us, conjuring the images into life: “I am sure you can see the figure of Hijikata Tatsumi on the stone. There he is! Watch him and Ohno Kazuo as I tell you their stories.” We all looked at the flickering wall and saw just what Kosuge wanted us to see: butoh heroes of the past, present day performers, broken fragments of his butoh research, flashing by in the not-yet darkness. But, Kosuge reminded us that in Tohoku, these seen-and-unseen spirits abound. The Serbian group made a classroom from giant chalkboards leaning against the wall. They wrote and danced statistics of the dead, the politics of ongoing ethnic troubles and the underlying tremble of fear adds up before us. We see how capitalism fails again and again to cover its tracks. There is a vocabulary for terror.

There was a boat for the Sisters from the Nordic Fluid States, to bring you on board for their new school. The boat was lit up with pink light, or was it blue? It was a saturated techno-color film to watch. Then the diver from the deep blue of the deepest Pacific dove into the dark bay with just himself. Does he always think: this might be the last or is there always one more deep blue dive?

We have come a long way on the jetty, where it tapers to a narrow ending. THEN WE SEE HIM: Lit in blue, we see Mick, glowing in the dark. He wears a space suit and swimming goggles with their own lights beaming from some far off outer space place. We scooped up the salt we had brought form around the world, from other seas, and scooped and scooped and tossed the treasures of the sea back into the sea.

We were hypnotized and hungry, when we turned to the sound of the Maori calls, the chants that enchant the seas, that speak to the earth, sky, water. We did not have to worry. We entered a wooden Stonehenge: with structures that kept us in a devout and reverential circle. Standing in our own constellation, we gazed up at the now deep black sky, shot with stars. The breakwater was our island of unknowing. The spokesperson said that we would find our way home, easily, by marking the lines between stars, the angles of our breath, the fine-tuning of our vision. We would find our way home in any kind of vastness or darkness.

Pilgrimage: Mt. Osore and the Crater Lake: Windmills at the gateway to the underworld

The buses, Gunhild said, are always off-schedule. But this meant you came early and met others wondering and waiting. The buses that took us all to Mt. Osore were the tourist wonder buses of Japan: big, comfy, adjustable seats, with huge windows for the views of the coastline, and the small towns. Our big buses, like Totoro’s cat bus, curve, smoothly along tiny roads, looping past old volcanic rocky terrain now smothered in green forests. At some point we learn that you have to have permission to visit Mt. Osore and its environments from May to September, but after that, because of the deep snow, no one enters even the forested area before the mountain. The temples, residence, and the whole area of sacred grounds, statues, rocks, and offerings are left alone, shut off and cut off from the world. No humans stay behind. Only a few stay near where the road is plowed.

We have a beautiful day of high gray clouds, some sun, soft silver lake waters, coolness.

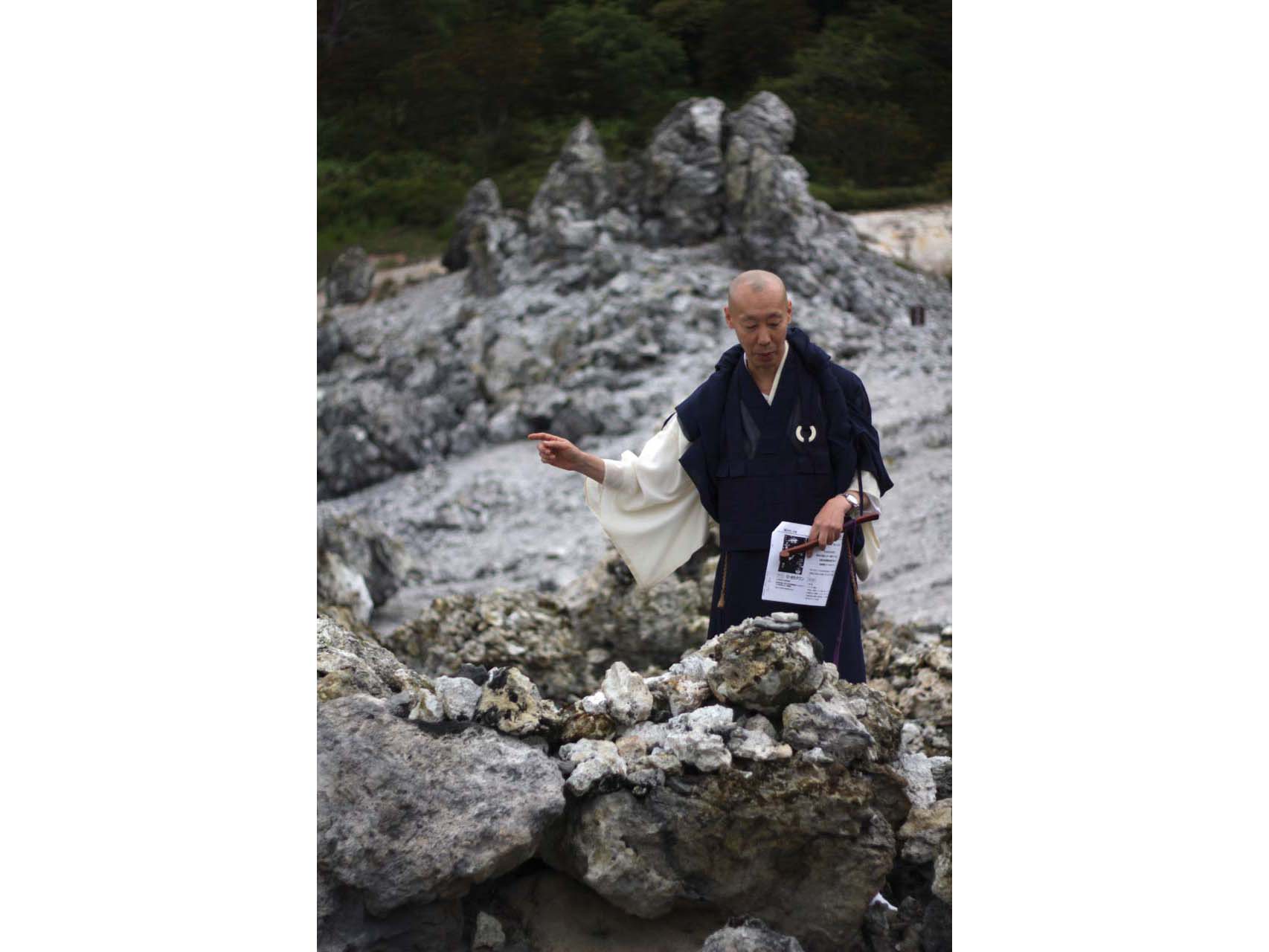

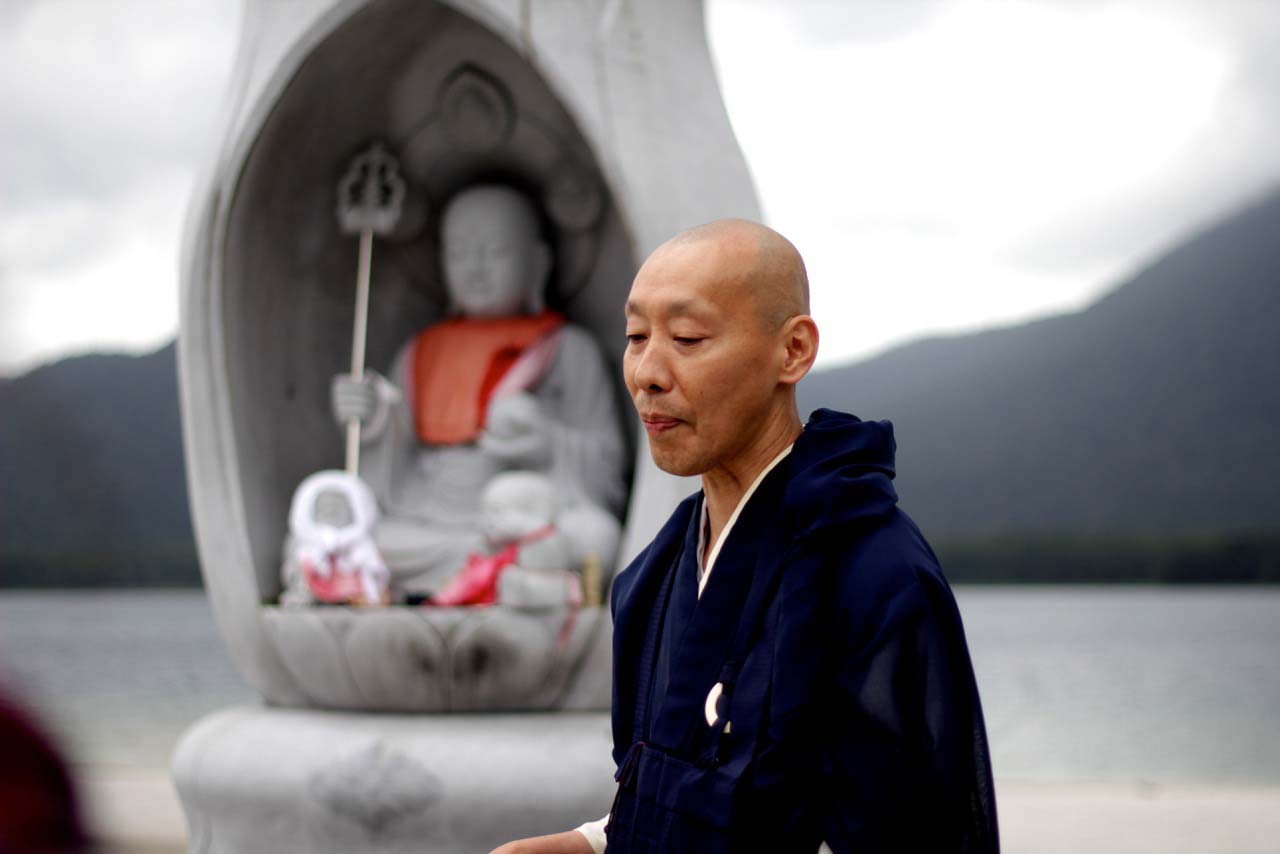

A two-hour journey bus journey brought all the participants of PSi 21 Fluid States Tohoku, on their first day, to one of the most sacred sites of Japan, inside the crater of a sacred mountain, Osore-zan (Mt. Osore). Mt. Osore is situated on the farthest northeastern peninsula, the Shimokita peninsula of the main island, Honshu, of Japan. The site is inside an ancient volcano’s crater, where a sulfurous lake, Usori, reflects the edges of the volcano and lies like a green-grey mirror of the sky in the midst of a pale silver to whitened rock-filled valley. The walls, paths, and walkways of several temples are the only structures in this lunar landscape.

But we cannot wander. We are herded into one beautiful building of the monastery-like complex. We take off our shoes. We leave our stuff somewhere. We go to the large dining hall, where we have incredible Buddhist vegetarian cuisine. We eat, we drink tea, and we hear a lecture on how to behave on the grounds. We understand that we will divide into two groups and follow special monks who will guide us and inform us about this special place.

We gathered at the temple but then took separate journeys out to the piled-stone sites and sulfur lake, in order to call on the spirits of the dead.

We are delirious to wander about the sulfurous landscape with its piles of stones, shrines, plastic pink windmills, and dressed-up stones, which are reminders that among the many dead souls that may be drifting about here, there are many children.

At one point we do get to roam about. Then we gather at a profound question and answer session where we hear from the monk about how relatives and friends of the dead leave material objects for the dead such as clothes, sweaters, food, and favorite toys. They only keep them for so long. There can be piles of stuff, so the monks have to get rid of it all. You can see these piles around the shelves of the temples and gathering places. There are stacks of clothes, objects, packages of food, which are left for the dead, just in case they may need them. Someone asks, “Do you recycle?”

Someone asks our Buddhist guide about the Itako, who are the famous mediums who communicate with the dead. It sounds like our guide thinks those are tourist-driven come-ons, and that there may be those who pretend to make contact with the dead relatives in order to make money. Maybe or maybe not. I went to the lake to call out to my dead mother, just in case she might be there wandering about.

I think we are all very high on the sulfur smells, the Buddhist meal, the lunar-like landscape. No one is moving very fast. Some of us wander to the lake, shimmering in its blue-green salt-thickness with blue and green and misted hills in the distance. It is still with ripples across the water. We are also still, or walking, stopping, looking, sensing. A few women find the hot springs bathhouse: AH! We buy the souvenir keepsake towels, imprinted with the lake, the temple, and mountains, and quickly enter the tiny bathhouse, the room thick with mist from the blue green pools. We strip and wash, and then immerse ourselves into these steaming waters. We hear the bus start up. We hear the calls for everyone on board. We reluctantly scramble back into our clothes but skip lightly into the bus, floating with minerals in the evening light. There is something here that pulls you into this landscape, which seems to float alongside the lake, whispering.

Passage: Aomori Museum Opening with the Sea (Butoh) Anthroposcenic Brides

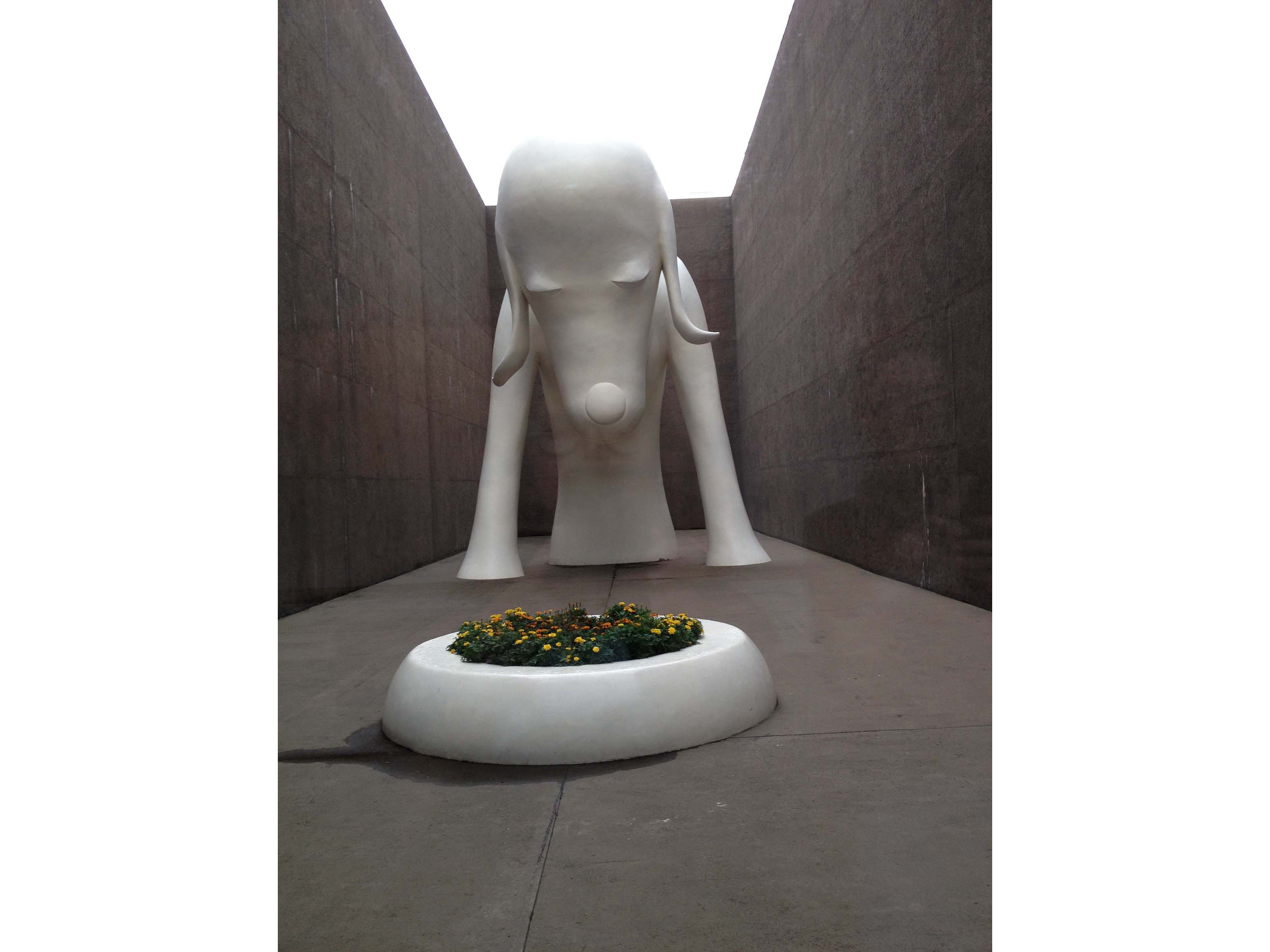

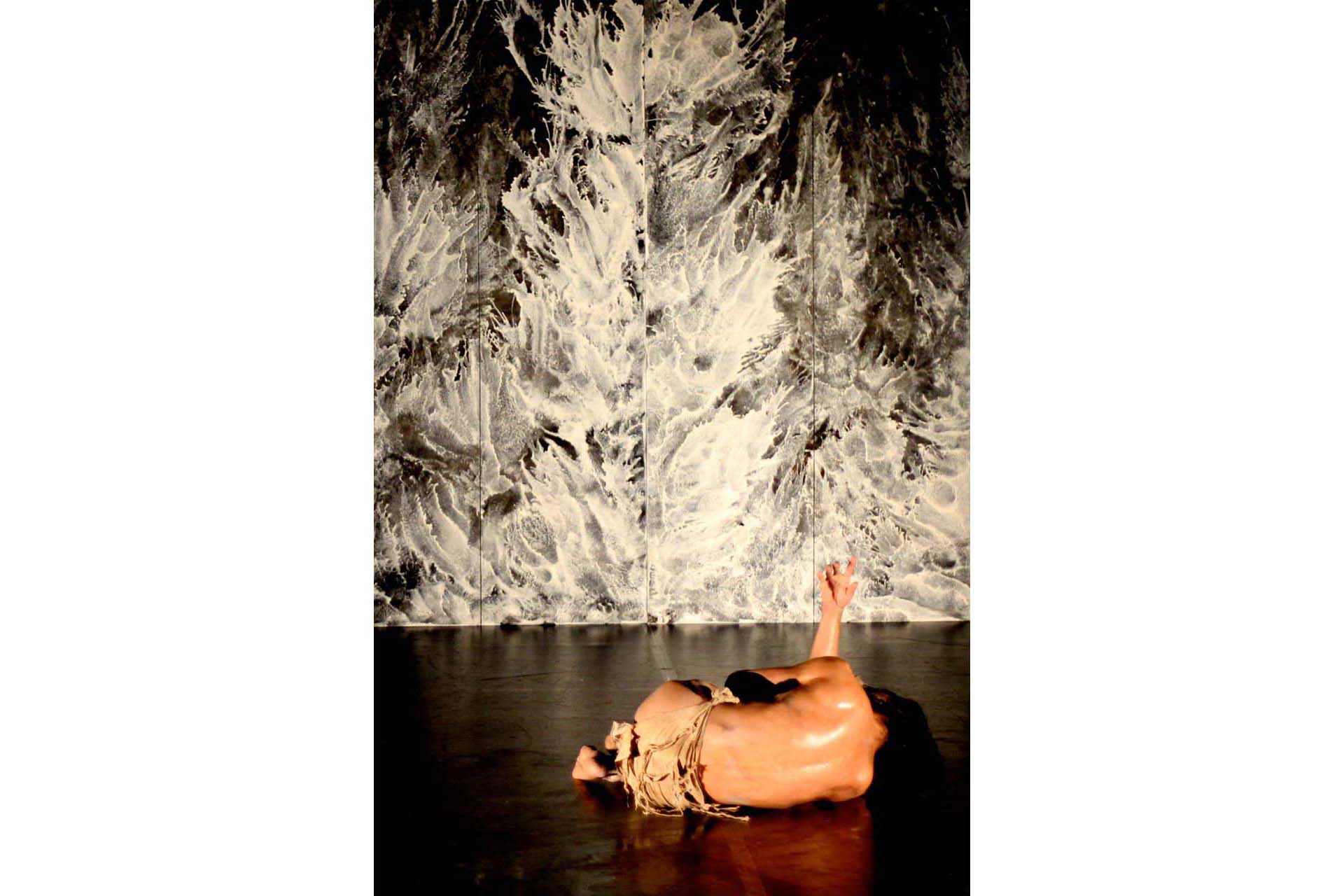

After Mt. Osore, we started the first morning at the Aomori Art Museum: a cool white structure that seems to be sinking into the dark, brown earth and concrete slabs of berms or swells of earth that make a labyrinth of space and time.

Remember that we had been to the place to contact dead souls, and now the Museum’s exhibit was on Bakemono, spirits and other haunted beings. Everyone can tell you: the whiteness of the building and the interior made doors invisible, elevators without numbers, and each level or space seemed unmarked and yet familiar. Someone said this is a building to get lost in. Where was I? You keep circling back to the same corridor.

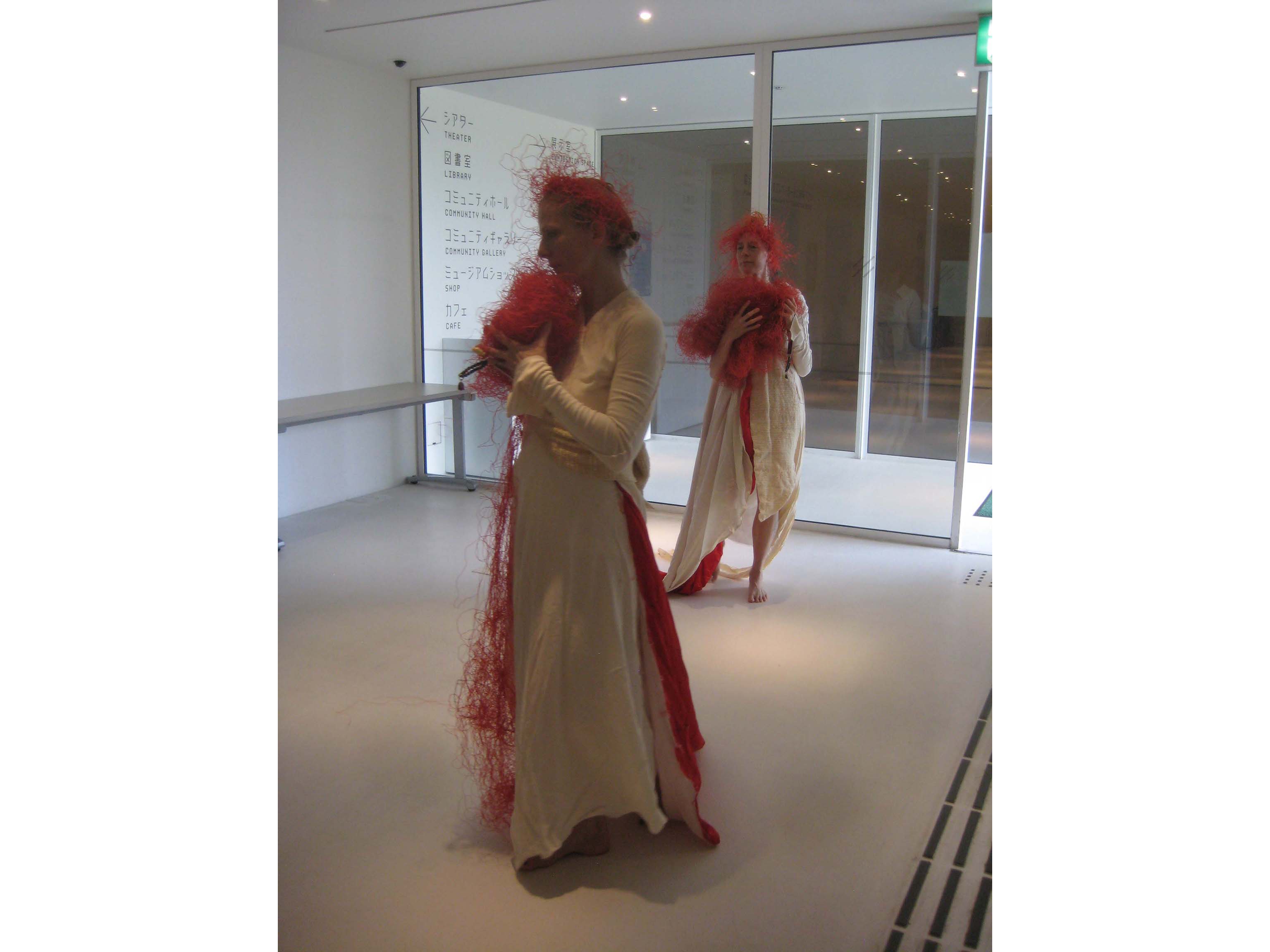

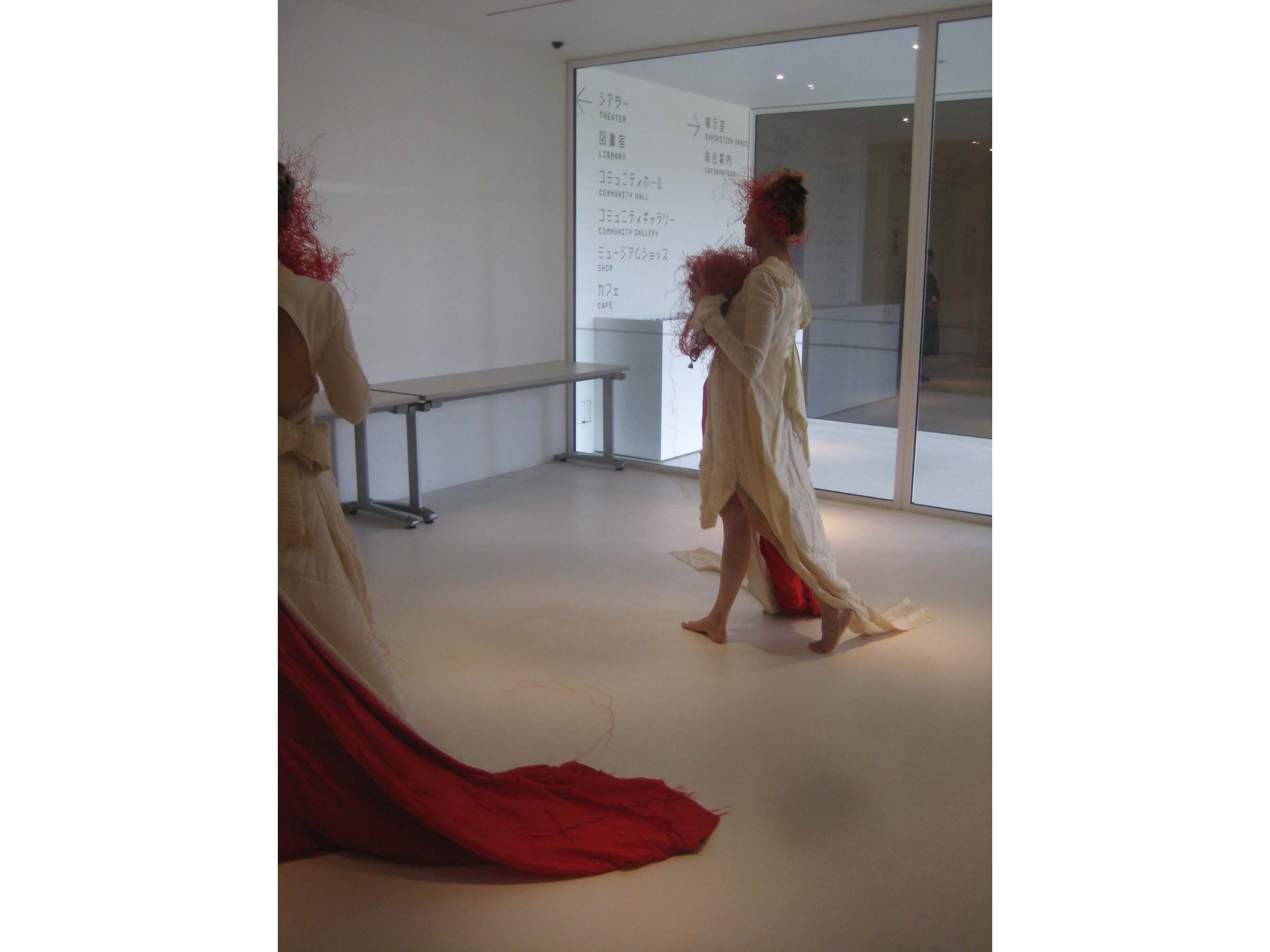

Outside on the vast green grounds of the museum, two “butoh” bride dancers began their slow ceremonious journey into the museum.

They dressed in white, long, satiny dresses and skirts, cut through with the blood red netting from the ceremony of passing the gifts from the Cook Islands to the Aomori, Tohoku gathering.

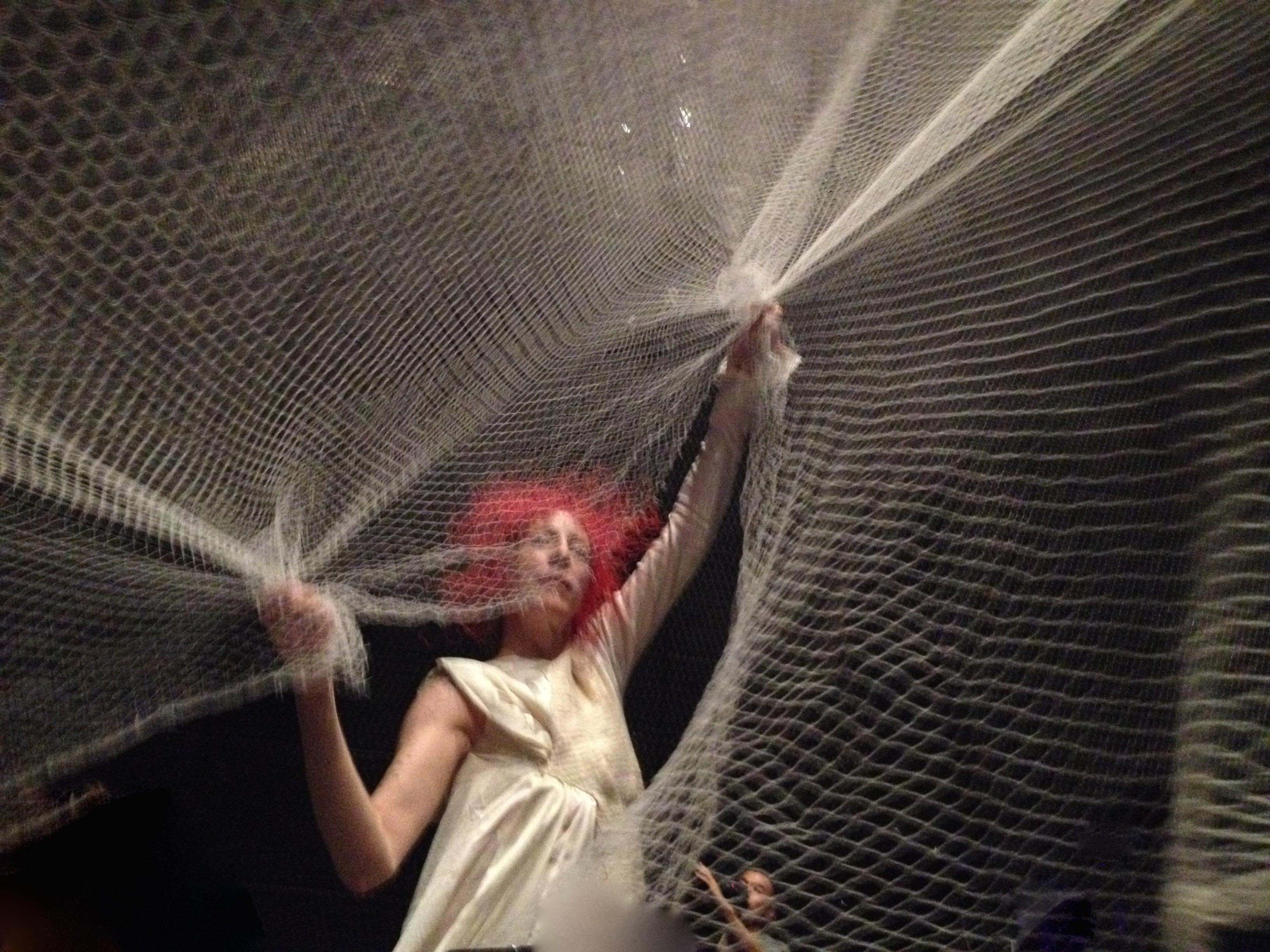

These are haunted anthroposcenic brides, netting the audience, a catch beneath the surface of the sea.

The brides remind us with their plastic netting that there are islands of human debris, which are cooking the sea, killing fish and coral, between here and the Cook Islands.

silence

Inside the museum’s labyrinth theatre, the brides capture the audience beneath their netting, as the Cook Island people call out a welcome to join them for PSi Fluid States, even as we commence and extend the voyage, walking on water, from Aomori, Japan.

The brides descend the staircase and present Hayato Kosuge with a 3D printed lei from the South Pacific. The white coral-like lei connects Kosuge’s bow to the Cook Islander’s warm greeting after this long voyage between the land and the sea, a ritual of unknowing, passage, and dwelling places. Somewhere in the darkness, the butoh dancers light the way, dancing with ghosts.

Walking on water, from Osorezan to Rijeka.

Works Cited

Ingold, Tim. The Perception of the Environment. London: Routledge, 2000.