Building upon emergent theorisations and praxes of decolonisation and decoloniality, this essay undertakes the critical work of suturing diverse understandings and practices of these notions from a range of fields and contexts. I begin by examining the crucial distinction between (de)colonisation and (de)coloniality, before arguing that the complementarity of the two ultimately means that both need to be mobilised in the liberation of Native lands, Nations, and peoples. Next, I turn my attention to several key discussions that focus on questions of imperialism and decolonisation in the field of performance studies, tracing their trajectories, as well as exploring some areas of potential growth for the field. In the second half of the essay, I discuss instances of Indigenous decolonisation—from perspectives of creative, critical, and activist praxis—that relate to the issue of forced migration, with a particular focus on Indigenous practices of hospitality and its limits.

While projects and practices of decolonisation have arguably existed since colonial conquest, the discourse on decoloniality was initiated by Latin American intellectuals and most notably Peruvian sociologist Aníbal Quijano who, in the early 1990s, introduced the notion of the colonial matrix of power, as well as the compound concept of coloniality/modernity. As such a compound concept intimates, Quijano argued that coloniality and modernity are mutually constitutive: “the European paradigm of rational knowledge, was not only elaborated in the context of, but as part of, a power structure that involved European colonial domination over the rest of the world” (174). In contradistinction to “colonisation,” which Quijano specifically understood to be “a relation of direct, political, social and cultural domination” (168), “coloniality” instead refers to what Catherine E. Walsh and Walter D. Mingolo have described as the “complex structure of management and control […] the ‘underlying structure’ of Western civilization and of Eurocentrism” (125). Whereas colonisation is a practice of domination in which one group of people subjugates another and usually involves the transfer of a populace to a new territory (“Colonialism”), coloniality is an enduring epistemic and ontological complex—what Quijano has called a heterogenous historical-structural node—that often persists beyond colonial occupation.

Accordingly, the crucial distinction between decolonisation and decoloniality occurs along similar lines. In the broadest sense, decolonisation refers to the deliberate undoing of colonialism. More specifically, the concept signifies processes via which a colony is freed and becomes an independent and self-governing nation-state. In most instances, it is the colonised who are the agents of decolonisation. The term has gained increased popularity since 1945, and has been retrospectively applied to revolutions and liberation movements that occurred earlier in history. Mignolo, for instance, discerns several waves of decolonisation. The first took place in the Americas, and was “led by Creole or Mestizo actors of European descent” (123).[3] The second wave was activated by Indigenous populations in Asia and Africa (124). While efficacious in realising its aim of forming sovereign nation-states in place of former colonies, decolonisation most often leaves the logic of coloniality intact. Indeed, according to Mignolo, decoloniality emerged precisely to address the shortcomings of decolonisation (124). The intent of decoloniality after decolonisation is to delink from modes of knowing, sensing, and being inculcated by the colonial matrix of power. Hence, the analytics of coloniality shifted the terms of the conversation from a focus on the state (decolonisation) to an emphasis on knowledge and epistemology (decoloniality). Following Quijano, decoloniality implies epistemic disobedience. Mignolo argues that decolonial delinking requires political structures of governance that support people’s organisations and creativity, he writes: “epistemic and emotional (and aesthetic) delinking means conceiving of and creating institutional organizations that are at the service of life and do not—as in the current state of affairs—put people at the service of institutions” (126). In this understanding, decolonial praxes are both heterogenous and localised. They emerge rhizomatically from the specific needs and desires of distinct communities. As such, decoloniality has the potential to share common ground with an abolitionist politic and methodology that not only refuses oppressive state structures, but also proposes alternative paradigms of care in their place—community-generated processes that arise from the specificities of particular sets of circumstances.

In their influential—if contentious—2012 essay, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor,” Eve Tuck (Unangax̂) and K. Wayne Yang present an important critique of a practice that has become increasingly common over the past two decades: using the term “decolonisation” as an empty signifier frequently deployed on the understanding that it can be “filled by any track toward liberation” (7). In this light, any gesture toward Indigenous people that does not address Indigenous sovereignty or Indigenous rights—or that advances a thesis on decolonisation without regard to the unsettling or the deoccupation of land—would be considered equivocal. Simply put, decolonisation is nothing less than the rematriation[4] of Indigenous land and life. This is not a move towards reconciliation, which, Tuck and Yang argue, is bound up with settler aspirations that relate to fantasies of innocence; rather, it is a move towards unsettling that very innocence in the interests of furthering concrete actions that have the potential to open up possibilities for Indigenous self-governance and well-being. After invoking Frantz Fanon’s notion of decolonising the mind as the first step in overthrowing colonial regimes, Tuck and Yang proceed to offer some further reflections: “Yet we wonder whether another settler move to innocence is to focus on decolonizing the mind, or the cultivation of critical consciousness, as if it were the sole activity of decolonization; to allow conscientization to stand in for the more uncomfortable task of relinquishing stolen land” (19). Although this line of reasoning initially appears to contrast with the claims regarding decoloniality that I have previously outlined, Tuck and Yang do not reject delinking or epistemological disobedience outright; they simply insist upon the imperative of decolonialisation understood as land rematriation. While it is vital to draw clear distinctions between decoloniality and decolonisation, the two are deeply entangled—and, I argue, both are not only requisite for a comprehensive process of undoing settler-colonial systems and epistemologies but mutually supportive in that undertaking.

This bold imperative of rematriation is exacting and has the potential to unsettle the settler—both figuratively and literally. The demand for land restitution threatens the core identity, material safety, and inviolability of the settler under the logic of colonialism. Where is the settler to go? In many—if not most—instances there is no clear or easy path back to one’s place(s) of origin. The worldview, the very ground upon which the settler stands is called into question. This provocation is not simply intellectual. The emotional, psychic, and logistical implications are profound. What, then, would such a process of land recovery look like?

As Walsh and Mignolo argue, processes of decolonisation and decolonial praxes are pluriversal and interversal. New Mexico-based Indigenous collective The Red Nation offers one such vision of land restitution outlined—in considerable detail—in their jointly authored book The Red Deal (2021). The text itself is dubbed “a manifesto and movement borne of Indigenous resistance and decolonial struggle” (5). The manifesto and programme certainly do not represent the perspectives of all Indigenous communities of Turtle Island. They were, however, not only collectively conceptualised and authored but also developed in consultation with numerous Indigenous nations across the Americas. The Red Nation writes “‘Land back’ strikes fear in the heart of the settler. But […] it is the soundest environmental policy for a planet teetering on the brink of total ecological collapse. The path forward is simple: it’s decolonization or extinction. And that starts with land back” (7). The short volume elucidates various dimensions of the land back movement and the concrete actions its realisation would entail. Even while acknowledging the potential—or probable—affective difficulty for the settler in the face of the proposed land recovery, by giving the idea shape and offering a more detailed description of their vision of decolonisation, The Red Nation potentially mitigates (some) settler anxieties. They write “Land back means the return of just relations between the human world and the other-than-human world” and further:

Indigenous laws and governance systems would reemerge in place of federal Indian law. Treaties would be enforced, not by the US government, but by Indigenous nations. Land back would become mandatory, ushering in a different type of development and reconstruction of our fundamental relationship to land not premised on ownership but on collective well-being. Transforming our relationship with the land would create conditions for caretakers (who aren’t exclusively Indigenous) to inherit the Earth; to work with, take care of, restore, and heal the land as diverse workers whose labor is bound, quite literally, with the land itself. (29)

Such a vision of decolonisation does not necessarily imply the dispossession of settlers. Rather it puts forward Indigenous-centred leadership and the “uniting [of] Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in a common struggle to save the Earth” (30). In the scenario proposed by The Red Nation, the stewardship of the land is returned to the original caretakers of Turtle Island so that they may both resume and further develop traditional restorative practices. The Red Nation argues that Indigenous political structures and economic systems do not apply only to Indigenous people: “Our liberation is bound to the liberation of all humans and the planet” (30). Envisioned thus, decolonisation serves not only Indigenous communities but everyone. Our collaboration and collective action is indispensable for its realisation. The Red Nation calls for grassroots organising—“change from below and to the Left” (34)—and the adoption of the principles outlined in the manifesto to the local, tribal, or regional context.[5] This approach—adapting certain guiding postulates to the specificity of the local—has the potential to create pluriversal solutions, which are nevertheless aligned with one another.

While the preceeding offered a broad—if non-exhaustive—overview of some of the discourses of decoloniality and decolonisation, I will now narrow the focus to examine how these issues figure in the field of performance studies specifically. In 2006, TDR: The Drama Review, published a comment by Jon McKenzie titled “Is Performance Studies Imperialist?” (5-8). In it, McKenzie draws attention to—among other things—the linguistic imperialism of Anglophone performance studies and the complicity of the field with US imperialism more broadly.[6] While the conceptual framework of (de)colonisation may have of late become more operative than imperialism,[7] the intimate intermingling between the two allows for a continuation and alignment between similar lines of discourse, which have arisen within performance studies.

Subsequent critiques in and of the field have generally emerged under the rubric of decolonisation. Sruti Bala, for instance, offers an astute discussion of the empirical inclusion and epistemic discontinuity of the additive logic of “decolonising” the academic canon specifically in the theatre and performance studies classroom. She urges scholars and pedagogues to “recognise how much epistemic privileges are ingrained in our disciplinary histories and challenge them on an ongoing basis” (340). In a similar vein, Swati Arora builds upon Tuck and Yang’s understanding of decolonisation, as further supported by the work of Sara Ahmed who argues that “using decolonisation as a metaphor recentres whiteness” (quoted in Arora 13). Arora similarly emphasises the epistemic violence that is inherent within the field, by calling attention to the fundamentally extractive nature of academic research and pedagogy (16).

Both Arora and Bala build their arguments on the foundational work of Diana Taylor as charted in her influential 2003 book The Archive and the Repertoire. Indeed, the relationship between the archive and the repertoire and the fold of practice and theory seems fundamental to discussions of decoloniality and decolonisation. Mignolo and Walsh emphasise the crucially reciprocal relationship between theory and practice—a key premise and core commitment of performance studies, and undoubtedly a pivotal contribution of the field to contemporary critical discourses. This overlapping terrain can prove fertile ground for the development and interanimation of both fields. Performance studies is well positioned to advance the analytics and praxes of both decoloniality and decolonisation. The field’s deep-seated and long-standing investment in questions of agency, behaviour, embodiment, identity, performativity, and representation; its attention to aesthetic, quotidian, and ritual performances; its dynamic, open, processual, and relational nature lends itself to productive borrowings and exchanges with decolonial studies. It is important to emphasise that such intimate connections between theory and practice are also to be found in Indigenous methodologies, where the process moves from reflection, to dialogue, to action—looping in on itself again and again (The Red Nation 144). Interrelationality is decisively underscored in these latter methodologies, along with the collective and dialogical aspects of what is ultimately a community-generated process.

Stephanie Nohelani Teves (Kanaka Maoli) has recently staged an important intervention in the field of performance studies, arguing that its scholars “need to take seriously the critiques of settler-colonialism and indigeneity coming out of Native Studies” (133). Various theorisations of settler-colonialism—understood here, after Dean Itsuji Saranillio’s formulation, as a subset of colonialization and a specific formation of colonial power that “destroys to replace” (quoted in Teves 133)—can help performance studies scholars, Teves argues, analyse performance “not merely as moments, spectacles, or events, but as pieces and processes of a legacy of settler colonialism that Patrick Wolfe famously claims is a ‘structure, not an event’” (133). Taylor’s earlier discussion of the iterability of the scenario of discovery—that is, the ways in which the colonial encounter and conquest is continuously repeated and reenacted with variation in the present—similarly points to the structural and systemic nature of colonisation more broadly and settler colonialism in particular (Archive and the Repertoire 53–78).[8]

In consonance with Tuck and Yang’s critique, Teves argues that Native performances that are merely celebrated in ways that do not connect them to contemporary Indigenous struggles for sovereignty obscure their cultural signification and political force. Teves further notes that one of the main reasons that Native studies has been resistant to performance studies is the latter’s integration of poststructuralist theories that question the essential nature of identity, subjectivity, and origin (136-137). She sheds light on the ways in which poststructuralist claims threaten the very stability of Indigenous identity: “Many Natives would shudder to think that we ‘perform’ our indigeneity (i.e., our Nativeness)”; and holds that theorizations of (non)origins have “contributed to the erasure of indigeneity and its lived consequences” (137). Crucially, Teves’ analysis puts pressure on the field’s fundamental epistemic attachments. What are the limits of performance studies scholars’ willingness to engage in epistemic disobedience in the name of decoloniality?

The title of this essay invokes the promise of lessons that can be gleaned from Indigenous revolutionary action. While I do not purport to offer a globalised programme here, I am advocating for pluriversal decolonial praxes and practices of decolonisation that emerge from the specificities of a myriad local contexts—the aggregation of what Paul Gilroy has called “small acts,” or the “million different little experiments” (166) called for by Mariame Kaba, because—as James Baldwin once put it: the impossible is the least that one can demand.[9]

Towards a practice of decolonisation:

In what follows, I consider Indigenous hospitality as one example of a mode of decolonisation, a strand of decolonial praxis within broader infrastructures of Indigenous caretaking.[10] In particular, I explore various instances of coalitional solidarities between Indigenous artists, scholars, and activists on the one hand, and (im)migrants, refugees, asylum seekers, and other displaced persons, on the other. I contend that creating divisions between similarly positioned but differing groups of systemically oppressed peoples is a tactic of the settler-colonial system aimed to maintain power divisively. Working in solidarity across difference directly refutes ongoing colonial ideologies, practices, and institutions and subverts regimes of border imperialism.[11] The issuing of Aboriginal passports to asylum seekers by Robbie Thorpe, of the Treaty Republic, and Ray Jackson, the president of the Indigenous Social Justice Association, is one instance that highlights the power of such solidarity and its potential to subvert the colonial nation state (“More than 200 migrants to receive Aboriginal passports”).[12] This interventionist action simultaneously acknowledges the sovereignty of Indigenous peoples and provides sanctuary to refugees.[13] While some of the actions of Indigenous solidarity with refugees that I reference below—especially the acts of welcoming and hospitality—have brought about comparable disruptions, other performative gestures, such as meaningful refusal, have instead constituted critical interventions that mark the limits of hospitality and designate sovereign spaces that lie beyond the realm of colonial governability.

In their aforementioned essay, Tuck and Yang argue that “because settler colonialism is built upon the entanglement of the triad structure of settler-native-slave, the decolonial desires of white, non-white, immigrant, postcolonial, and oppressed people can similarly be entangled in resettlement, reoccupation, and reinhabitation that actually furthers settler colonialism” (1). Even while offering this important caveat, Tuck and Yang still afford the immigrant a separate ontological status, one that is not necessarily subsumed under or elided with the category of settler. Indeed, they emphasise this crucial distinction in unambiguous terms: “Settlers are not immigrants. Immigrants are beholden to the Indigenous laws and epistemologies of the lands they migrate to. Settlers become the law, supplanting Indigenous laws and epistemologies. Therefore, settler nations are not immigrant nations” (7). While, following this assertion, countries such as the US would not, as a whole, be considered immigrant nations, it is still possible to imagine individual immigrants, or even communities of immigrants, living within a settler nation and retaining their immigrant status by respecting and adhering to Indigenous codes. In fact, the very category of “immigrant” is unstable and needs to be unsettled here. For the purposes of this writing, I will focus on a single aspect of the porousness and uncontainability of this category, by considering how it relates to both settler and Indigenous identities.

As Nicholas Bustamante and Cristóbal Martínez (Genízaro, Pueblo, Manito, Chicano) demonstrate, the vast majority of immigrants entering the United States from Central America are either Indigenous or mestizo.[14] These migrants are following traditional—ancient—migratory patterns that predate colonial contact. Clearly, Indigenous and (im)migrant identities are not necessarily mutually exclusive. Even so, it is often the case that the settler-colonial nation state contests, and even usurps, the identity position of migrants for its own purposes—often to advance its own political aims. Bustamante and Martínez write:

throughout the U.S. and Latin America, if individuals are not perceived as the mythological pure blooded Amerindian, their indigenous status as mestizos is usurped by nation-state Eurocentric identities such [as] the aforementioned labels: Hispanic, Indo-hispanic, Latina/o and Latinx, thus making brown populations migrating to the United States vulnerable to dehumanizing labels, even though they very well might be following in the migratory and trade traditions of their indigenous ancestry. (19)

Contrary to popular media renderings of Central American—and other—migrants as “dangerous criminals” and the ongoing political rhetoric that erroneously presents immigration breaches as criminal—rather than civil—violations and criminalises immigrants and asylum seekers more broadly, not only do individuals have the right to migrate and seek asylum, but Indigenous peoples are fully justified in laying claim to the traditional migratory routes that have existed since time immemorial and preceded the violence of colonial borders.[15]

As the rallying cry of migrant justice activists proclaims, “We didn’t cross the border, the border crossed us,” members of Indigenous nations have long negotiated the brutal imposition of imperial borders of the colonial nation-state that cut across and sever sovereign Indigenous lands. In her 2014 book Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across Borders of Settler States, Audra Simpson (Kahnawà:ke Mohawk) powerfully conveys her crossings across the US–Canada border, which bifurcates the Mohawk reservation. Citing Cayuga chief and activist Deskaheh (1873–1925), Simpson upholds that the institution of citizenship is a colonising technique (136) and theorises the violent forms of (mis)recognition instantiated by the apparatus of the colonial state. Simpson’s poignant descriptions of her fraught passages across borders—replete with intrusive questioning and demeaning treatment by border authorities—evidence the daily indignities meted out by the colonial state apparatus. In these charged encounters with the nation-state, Simpson was variously not acknowledged as a North American Indian, interpellated as a US-American subject, and misrecognized as an immigrant. In one instance, Simpson was sent to the Immigration and Naturalization Service by border authorities in New York City. The lack of recognition and misrecognition of the Indigenous subject, the mixing up or conflating of various categories of colonised subjects that fall outside of full colonial recognition suggest the relative interchangeability of abject others within settler-colonial systems and states. Drawing on the politics of refusal,[16] in both her theorising and lived daily practice, Simpson disrupts the business-as-usual flow of colonial borders. Such quotidian acts of refutation enacted by Simpson put a dent in the system.

In what follows, I attend to coalitional solidarities between Indigenous artists, scholars, and communities and (im)migrants—Native and non-Native alike.[17]

Arguably, most—if not all—traditional communities had and continue to have practices of hospitality as a significant characteristic of their society. Hospitality is likewise a salient feature of the cultures of Indigenous Nations of Turtle Island. According to Nick Estes, an Indigenous scholar, activist, and member of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, hospitality is quite simply a quality that defines what it means to be Lakota: “After all, one ceases to be Lakota if relatives or travelers from afar are not nurtured and welcomed” (59). Receiving and welcoming others is constitutive of the identity of many Indigenous communities. The Red Nation’s manifesto similarly affirms the ethos of care—of which the practice of hospitality is a subset—as a core Indigenous value:

Healing the planet is ultimately about creating infrastructures of caretaking that will replace infrastructures of capitalism. Capitalism is contrary to life. Caretaking promotes life. […] caretaking is at the center of contemporary Indigenous movements for decolonization and liberation. We therefore look to these movements for guidance in building infrastructures of caretaking that have the potential to produce caretaking economies and caretaking jobs now and in the future. (The Red Deal 108)

Moreover, the manifesto makes clear The Red Nation’s solidarity with immigrants, as well as their ongoing commitment to migrant justice. The third of their fourteen recommendations reads as follows:

Open all borders. First World countries must assume all responsibility for the hundreds of millions of people that will be forced to migrate due to capitalist-driven climate change. They must eliminate their restrictive immigration policies and instead offer migrants a decent life with full human rights guarantees in their countries. (The Red Deal 134)[18]

Recent instances of artistic and activist practice further reveal the emergent alliances between Indigenous and refugee populations.

This image titled “Decolonize Immigration” (2012)—a poster designed and printed by Métis/Wiisaakodewini artist Dylan Miner—encapsulates this convergence explicitly equating Indigenous sovereignty with immigrant rights and linking both issues to decolonisation.

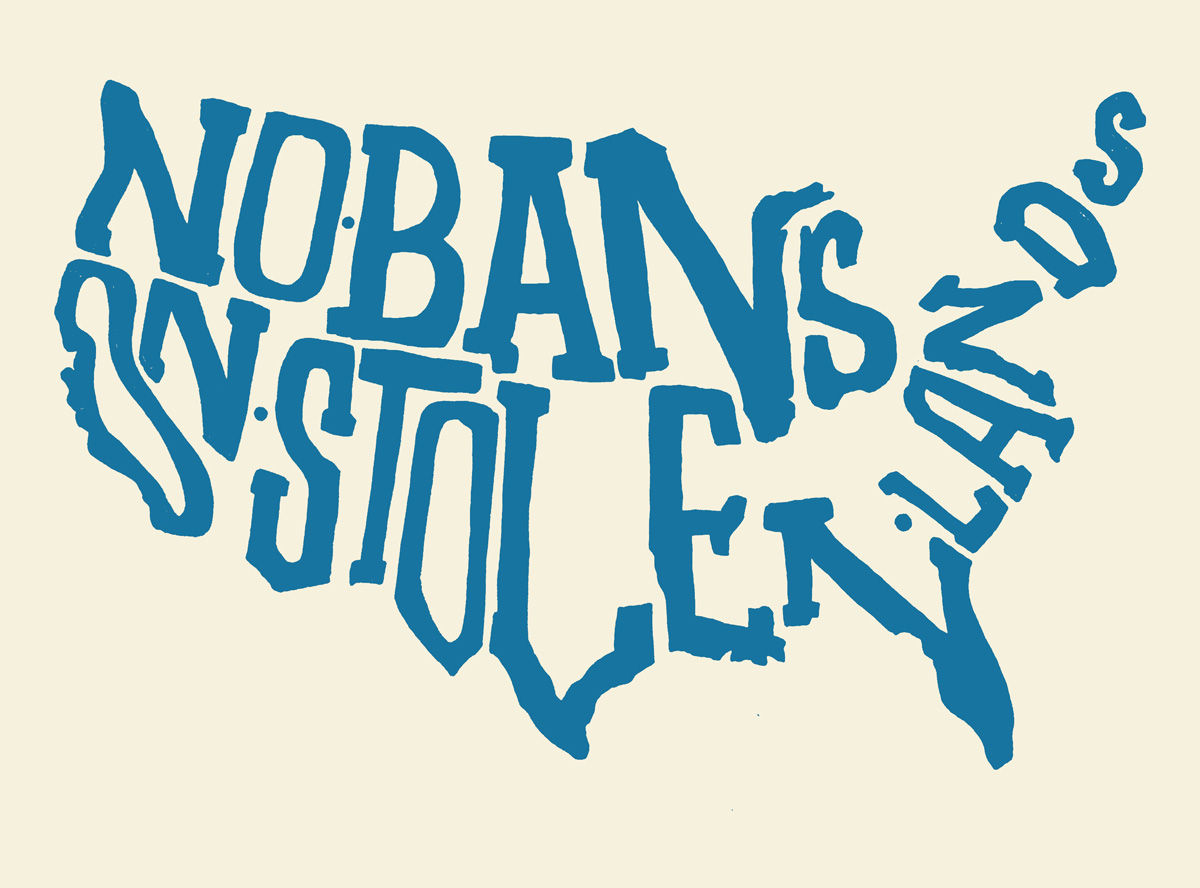

A later poster by Miner, “No Bans on Stolen Lands” (2017), similarly connects Indigenous issues to immigrant rights, this time by making a clear reference to a series of executive orders issued by the Trump administration, prohibiting the travel and resettlement of refugees from a select group of predominantly Muslim countries.

Miner is a socially engaged interdisciplinary artist and scholar whose work brings together traditional and contemporary practice. In the ongoing project Native Kids Ride Bikes, Miner works with Native urban youth to build lowrider bicycles, which incorporate traditional materials, colours, and symbols that reflect the various tribal heritages of the individual co-creators. Not only does the project gesture towards the ancient migratory practices of Indigenous peoples that I have previously mentioned, but also hints at the contemporary desires—and needs—that Native peoples have for sustainable transportation options. Miner’s 2014 book, Creating Aztlán: Chicano Art, Indigenous Sovereignty, and Lowriding Across Turtle Island, makes these connections explicit by taking the practice of lowriding as a metaphor for the movement of Indigenous peoples through space.

Another iteration of the project titled Dismantling the Illegitimate Border (2012) redeploys the practice of lowriding to figuratively dismantle borders and other violent impositions of settler colonialism. In this instance, in addition to the traditional trimmings, the bikes are also fitted with baskets that contain functional printing presses.

The undoing of colonial borders is also one of the central themes of The Repellent Fence (2015), a project by the Indigenous art collective Postcommodity.

Sam Wainwright Douglas’s 2017 film follows three members of Postcommodity—Raven Chacon (Diné), Cristóbal Martínez, and Kade L. Twist (Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma)[19]—as they construct a two-mile long land art work that straddles the US-Mexico border.[20] Aided by the communities on both sides of the border the artists installed a series of twenty-eight large-scale inflatable spheres emblazoned with an insignia known as the “open eye” that has existed in Indigenous cultures from South America to Canada for thousands of years. In their words, the project is “a metaphorical suture stitching together cultures that have inhabited these lands long before borders were drawn” (in Douglas). The installation accentuates the interconnectedness of the land, people, cultures, and communities in the US-Mexico borderlands. Beyond demonstrating a deep intersectional and coalitional solidarity, the work addresses the complexities and nuances of the intersection of migration and Indigenous sovereignty.

In his 2016 essay “Welcoming Sovereignty,” Stó:lō scholar Dylan Robinson makes an important intervention in the theorisation and enactment of the limits of hospitality. Effectively mobilising a mode of performative writing that asks non-Indigenous readers to skip over a section of the text intended for a Native audience only, Robinson effectuates a space apart—marking a sovereign space, what he calls a “different place of gathering” (7). Having established that Indigenous sovereignty is not held in documents or objects, but instead constituted through action (6), he writes “this essay seeks to enact sovereignty with readers, through a particular action of refusal that begins with the injunction not to read” (7). Robinson asserts that practices of hospitality—as in welcoming guests into places—implicate sovereign control signalled through rules of the space. He further elaborates:

To enact settler exclusion is a strategy of sovereignty that defines a space outside of Indigenous knowledge extractivism, where our knowledge is not simply a resource used to Indigenize. Exclusions are seldom enjoyable experiences […] There is a need to define Indigenous space ungoverned by the prerogatives of multicultural enrichment. Such spaces take shape through sovereign re-marking of boundaries and borders that contrast the ways in which Indigenous traditional and ancestral territories are traversed every day without thought. (20)

By indicating the limits of hospitality and designating the boundaries of sovereign space beyond the realm of colonial governability, Robinson performs a meaningful refusal of unwelcome encroachments—both literal and figurative—while also demonstrating the elisions and abrogations of Indigenous sovereignty. Recognising and contemplating the limits of welcome and hospitality reveals a great deal about the practice itself. It points to the—often unspoken or unconscious—rules and protocols, which are rendered visible only by means of breaches. Attending to the limits of hospitality, sitting with the discomfort of ruptures or exclusions, allows for a deeper understanding of both practices of care and praxes of sovereignty, which are inevitably intertwined.

Alongside such deep-seated expressions of solidarity and coalitional action, as well as such performative and theoretical explorations of the limits of hospitality, Indigenous artists and scholars are exploring practices of care as an alternative to colonial structures and systems. Charles Sepulveda (Tongva and Acjachemen), for instance, proposes Kuuyam, the Tongva notion of guest, as a decolonial possibility and practice. This potential decolonial modality offers a relation in which the non-Native is a guest of the tribal people (41) and of the land itself, which “contains spirit and is willing to provide” (54). This relationship—which, more broadly, is also an Indigenous method for the proactive alleviation of violence—should be proffered, then chosen, but not imposed (54). Sepulveda establishes the deep-rooted practices of Indigenous hospitality that existed before colonial contact. While acknowledging that these very praxes of care and hospitality proved to be some of the very mechanisms through which Indigenous peoples came to be colonised, Sepulveda nonetheless advocates the upholding of these traditions and values: “The earth, which has been treated with disrespect by humans on a global scale, continues to be welcoming. Following the teaching of the earth, Indigenous peoples can also continue their traditions of being welcoming” (54). Sepulveda’s Indigenous theorisation of Kuuyam thus succeeds in unsettling the dialectic between Natives and settlers, through the Tongva understanding that all non-Natives are potential guests of both the tribal people and the land itself (41). He writes:

Kuuyam can disrupt settler colonialism. It can support bringing balance back to the environment, re-centering Indigenous peoples and the decolonial struggles to revitalize cultural elements […] Kuuyam is an abolition of institutionalized hierarchical conceptions of human difference that separate people by race, origins, gender, and sexuality. Instead, Kuuyam establishes relations beyond difference in a non-hierarchical manner. (54–55)

There is some congruity between Tuck and Yang’s understanding of the immigrant as someone who is beholden to Indigenous epistemologies and laws and Sepulveda’s discussion of Kuuyam. The position of host and guest implies both privileges and responsibilities, and presumably the guest on Native land would fulfill their bidding by honouring and adhering to Indigenous codes. What is more, Sepulveda’s invocation of Kuuyam also raises the possibility of the settler being transformed into a guest, even though he acknowledges the challenges in—or, rather, the near impossibility of—achieving such an outcome:

Residents of Tongva land (Tovaangar), for example, can be Kuuyam and not act as colonizers or seek to further domesticate the environment for their own benefit. They can be welcomed guests, and not looked at by the Native community as settler colonizers—no matter their skin color, histories, or origins. (54)

The very possibility of a change in status from settler to guest suggests that the concept of “settler” signifies both a set of behaviours and a structural location—both of which have the potential to be transformed. Framed thus, decolonisation invites more reflection, theorisation, and collective experimentation in praxis.

Returning to the terms introduced at the beginning of this essay, practices of decolonisation and decolonial delinking—a necessarily generative process that gives rise to alternative epistemologies—operate in tandem as they are mutually constitutive and reciprocal. The field of performance studies has the potential to illuminate the dynamic, processual, and relational natures of these unfoldings. These processes need also be turned inward to recalibrate our own paradigms. Toward that end, we should take seriously the heed to loosen our hold on the field’s core epistemic attachments; shed extractivist methodologies; and—taking cues from Indigenous leadership—actively engage in theorisations of decoloniality that both mobilise and are mobilised by practices of decolonisation, which arise from the specificities of our individual contexts.

Indigenous and other praxes of hospitality are neither the assumed privilege nor the right of the guest. Rather, they express the agency and dignity of the host(s) and hold the same potentiality for the guest(s). Hospitality, as well as the enactments of its limits, are pluriversal and localised. They arise from concrete contexts and circumstances—the specificity of the needs and desires of the host(s) and guest(s). The location, duration, participants, (un)spoken protocols, (un)conscious intentions, activations of space, objects, and attendant acts—their efficacies, misfires, and failures—are all open to imaginative play and revision, in an endless process of ongoing experimentation and reiteration. Scenarios of hospitality are precarious. They open us up to vulnerability—our own and that of the other. They hold the potentiality of encountering the unknown. They also portend transformation and the possibility—especially through iterative practice—of building sustainable long-term relationships of accountability.

[1] I gratefully acknowledge the Indigenous artists who gave permission to publish their work within the context of the present essay: Jaque Fragua, Melanie Cervantes, Postcommodity, and Dylan Miner. I am deeply grateful to Nesreen Hussein for her incisive editorial work on this essay as well as to the two anonymous reviewers, whose comments and suggestions not only helped enhance the present text but will continue to inform my future work.

[2] To situate myself briefly, I am a Polish Jew of Ukrainian descent. I came to Turtle Island as a child (political) refugee. I currently live and work on Tiwa territories. These lands, colonially known as New Mexico, are unceded Indigenous territories presently home to twenty-three tribes—nineteen Pueblos, three Apache tribes, and the Diné (Navajo) Nation.

[3] There are, however, numerous occurrences of Indigenous-led revolts and decolonisation struggles. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 is one instance of a successful—if impermanent—decolonisation effort led by Popé, a Tewa religious leader from Ohkay Owingeh, who was the principal strategist of the Indigenous uprising. See Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz’s Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico (2007: 41-45).

[4] The co-director of the Indigenous Law Insititute, Steven Newcomb (Shawnee, Lenape), defines rematriation as the process of restoring “a people to a spiritual way of life, in sacred relationship with their ancestral lands” (3).

[5] The Red Nation calls for a revolution that recentres our relationships to one another and the Earth over profits—as an alternative to neoliberal capitalism.

[6] McKenzie’s comment initiated a larger conversation, which resulted in a multi-part forum published in the journal over a period of the ensuing year.

[7] Although “imperialism” and “decolonisation” have diverse definitions contingent upon disciplinary genealogies, the two concepts are sometimes difficult to distinguish. Imperialism, before Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, was commonly understood as (European) dominance and capitalist expansion. However, Mignolo argues that—from a decolonial perspective—colonialism can be perceived as the complement of imperialism: “there is no imperialism without colonialism and […] colonialism is constitutive of imperialism” (Mignolo and Walsh 116).

[8] Taylor’s more recent work, ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence (2020), advances her earlier discussions of the theories and praxes of decolonisation.

[9] My references here to Black revolutionary intellectuals is neither incidental nor incongruent. While beyond the scope of this essay, decolonisation struggles are not only congruous with an abolitionist politic and praxis but deeply interconnected and potentially mutually supportive. Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) abolitionism, as theorised by Kaba and others, offers crucial interventions that help undo oppressive systems and affords praxes of liberation that are both creative and experimental. For Kaba, the emphasis of abolitionism is on fashioning new modalities of redress. She asks how it might be possible to resolve harm and violations without resorting to brutality and advocates for new structures of community-based accountability embedded in modalities of restorative and transformative justice. Abolitionist visions are utopian, yet Kaba contends that anything less would be a failure of the imagination (137).

[10] This turn towards practices of care has grown out of my research on forced migration. Instead of focusing on the so-called “problem” of migration, I engage with ways in which displaced persons are and can be received—the potentialities and limits of hospitality. Examining the situation of recent arrivants to Turtle Island—among other places—necessitates a consideration of Indigenous sovereignities, as well as the relations and relationships between Native and (im)migrant communities.

[11] In her powerful work Undoing Border Imperialism (2013), Harsha Walia argues that border imperialism “works to extend and externalize the universalization of Western formations beyond its own boundaries through settler colonialism and military occupation, as well as through the globalization of capitalism” (39–40).

[12] While this example allows us to imagine otherwise, at present the first and only interface for most immigrants, refugees, and asylum seekers is with the apparatus of the colonial regime. It is to the colonial nation-state that the vast majority of appeals for asylum or immigration are made.

[13] In an interview published on 6 August 2012 by the Green Left, Jackson stated: “The issuing of the passports cover two important areas of interactions between the traditional owners of the lands and migrants, asylum seekers and other non-Aboriginal citizens of this country. Whilst they acknowledge our rights to all the Aboriginal Nations of Australia we reciprocate by welcoming them into our Nations. It is a moral win-win for all involved in the process” (“More than 200 migrants to receive Aboriginal passports”).

[14] Many Indigenous scholars—Martínez among them—consider mestizo people to be Indigenous.

[15] Bustamante and Martínez draw attention to the fact that “Native peoples through the hemisphere moved across the four directions both for trade and migration in search of opportunities to prosper” (20).

[16] For instance, Simpson insists on her Mohawk identity when she is otherwise interpellated by state actors. For a fuller description, and an in-depth analysis of these border crossings, see chapter 5, “Borders, Cigarettes, and Sovereignty,” of Simpson’s Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across Borders of Settler States (2014).

[17] While my emphasis in the present text is on coalitional solidarities, to say that these can—at times—be uneasy alliances would be an understatement. As Dunbar-Ortiz writes, “The ubiquitous claim that the United States is a ‘nation of immigrants’ rings hollow to Native Americans and, indeed, distorts the history of the origin and development of the United States” (166). It is precisely for this reason that coalitional movements must include Indigenous self-determination and land rematriation as core issues and objectives of collective action.

[18] As mentioned earlier, although the Red Deal was developed in consultation with numerous Indigenous Nations across the Americas, it cannot possibly represent all the potentially divergent stances on immigration, and other issues, of the myriad of Indigenous communities and individuals. Similarly, by discussing various artists, scholars, and activist who engage with or advocate for theories and practices of Indigenous care and hospitality, I do not mean to suggest that all Native communities or persons share the same commitment.

[19] As of the time of this writing, Postcommodity is comprised of two members: Cristóbal Martínez and Kade L. Twist.

[20] According to Postcommodity, this project “put[s] land art in a tribal context.”

“Colonialism.” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/colonialism/.

“More than 200 migrants to receive Aboriginal passports.” Green Left, 932, 6 August 2012. https://www.greenleft.org.au/content/more-200-migrants-receive-aboriginal-passports.

Arora, Swati. “A manifesto to decentre theatre and performance studies.” Studies in Theatre and Performance, vol. 41, no. 1, 2021, pp. 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14682761.2021.1881730

Bala, Sruti. “Decolonising Theatre and Performance Studies: Tales from the Classroom.” Tijdschrift Voor Genderstudies, vol. 20, no. 3, 2017, pp. 333–345. https://doi.org/10.5117/TVGN2017.3.BALA

Baldwin, James. The Fire Next Time. New York: The Dial Press, 1963.

Bustamante, Nicholas, and Cristóbal Martínez. “Indigenous Asylum Seekers to the United States: Identities and Human Rights Beyond Borders.” Unpublished conference paper.

Douglas, Sam Wainwright. Through The Repellent Fence: A Land Art Film, 2017.

Dunbar-Ortiz, Roxanne. Roots of Resistance: A History of Land Tenure in New Mexico. University of Oklahoma Press, 2007.

Estes, Nick. Our History is the Future. Verso, 2019.

Gilroy, Paul. Small Acts: Thoughts on the Politics of Black Cultures. London Serpent’s Tail, 1994.

Kaba, Mariame. We Do This ‘Til We Free Us: Abolitionist Organizing and Transforming Justice. Haymarket Books, 2021.

McKenzie, Jon. “Is Performance Studies Imperialist?” TDR: The Drama Review, vol. 50, no. 4, Winter 2006, pp. 5–8. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram.2006.50.4.5

Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Duke University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822371779

Miner, Dylan A. T. Creating Aztlán: Chicano Art, Indigenous Sovereignty, and Lowriding Across Turtle Island. University of Arizona Press, 2014.

Newcomb, Steven. “Perspectives: Healing, Restoration, and Rematriation.” News & Notes, Spring/Summer 1995.

Quijano, Aníbal. “Coloniality and Modernity/Rationality.” Cultural Studies, vol. 21, nos. 2–3, March/May 2007, pp. 168–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09502380601164353

The Red Nation. The Red Deal: Indigenous Action to Save Our Earth. Common Notions, 2021.

Robinson, Dylan. “Welcoming Sovereignty.” Performing Indigeneity, edited by Yvette Nolan and Ric Knowles, Playwrights Canada Press, 2016, pp. 5–32.

Saranillio, Dean Itsuji. “Settler Colonialism.” Native Studies Keywords, edited by Stephanie Nohelani Teves, Andrea Smith, and Michelle H. Raheja, University of Arizona Press, 2015, pp. 284–300. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183gxzb.24

Sepulveda, Charles. “Our Sacred Waters: Theorizing Kuuyam as a Decolonial Possibility.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 7, no. 1, 2018, pp. 40–58.

Simpson, Audra. Mohawk Interruptus: Political Life Across the Borders of Settler States. Duke University Press, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780822376781

Taylor, Diana. The Archive and the Repertoire: Performing Cultural Memory in the Americas. Duke University Press, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822385318

———. ¡Presente! The Politics of Presence. Duke University Press, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1215/9781478008897

Teves, Stephanie Nohelani. “The Theorist and the Theorized: Indigenous Critiques of Performance Studies.” TDR: The Drama Review, vol. 62, no. 4, Winter 2018, pp. 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1162/dram_a_00797

Tuck, Eve, and K. Wayne Yang. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society, vol. 1, no. 1, 2012, pp. 1–40.

Walia, Harsha. Undoing Border Imperialism. AK Press and the Institute for Anarchist Studies, 2013.