Artistic border representations may offer a way to question the normative aspects that constitute a colonial space. Embracing this perspective involves decolonising the ways in which we look at the territories configured as such, thereby recognising the hierarchies of power and knowledge that have been enacted in their shaping. The research I present here was undertaken in the city of Ceuta, a territory that is configured as a Spanish enclave in the north of Africa. The contemporary city, encompassing an area of 18.5 km2, has been delimited by a triple border fence that has existed between it and Morocco since 1993, shortly after Spain’s accession to the European Economic Community and the entry into force of the Schengen agreement on free mobility. Since that time, Ceuta has undergone a functional and symbolic remodelling as an EU/Schengen border, thereby affecting the trajectories and expectations of people on the move who pass through the city (see work by Aris Escarcena, and Ferrer-Gallardo and Espiñeira).

At the functional level, the mandatory requirement for visas established between Spain and Morocco in 1991 was followed by the creation of a readmission agreement, the construction of the border fence, and the reconfiguration of checkpoints. These developments, which have become more sophisticated over time, brought about unprecedented changes in the neighbourhood relations and the conditions governing mobility on both sides of the border, as Leslie Gross-Wyrtzen and Lorena Gazzotti have shown. Indeed, the gradual deployment of tighter border security paralleled the reshaping of mobility dynamics in North Africa, consolidating countries such as Morocco as transit and destination nodes for migratory and exile movements, and affecting both national policies and the migration-foreign policy nexus (Fernández-Molina and Hernando De Larramendi 230). These characteristics have also made Ceuta, along with other Mediterranean border zones (such as Melilla, Lampedusa, and Lesbos) territories of investigative interest, which are being observed as “laboratories” of European bordering processes (Bialasiewicz 848; Campesi 70; Garelli et al. 813; Javourez et al.).

Bordering processes refer to the ways in which states, and supra-national entities such as the EU, define and regulate borders between themselves and others. These processes comprise an institutional assemblage of policies, practices, technologies, cultural conventions, and relations that affect the material and the symbolic order, given that space is socially produced (see Lefebvre) and comprises different layers of representations that touch on the imaginary and the referential. In this paper, I discuss the border on the symbolic plane, focusing on the implications that aesthetic filmic counter-representations may have on emancipating and transgressing the order they impose.

In the present context, we are witnessing a process of “spectacularisation” of migration and border crossings that operates on the basis of a migration–security–illegality nexus (De Genova 1190). The representational apparatus that is erected upon this nexus affects how we perceive, narrate, and enact borders (see also Binimelis-Adell and Varela Huerta). Thus, in the case of Ceuta, the images of people perched on the border fence, attempting to cross it, has become a global media icon of the so-called “Fortress Europe,” impregnating our imaginary to the point that if the fence does not appear on screen, it seems that we are not seeing a representation of the border. Indeed, we could argue that the border is performed in every act of fence-jumping that is recorded in an image and then publicly distributed, following the line drawn by Judith Butler in her seminal work on performativity. The “acts” create the “idea” in accordance with cultural conventions that set the norm, while obscuring the “genesis” of this production (Butler 522).

From a decolonial perspective, a critical reading in this respect prompts us to examine the coloniality of these representations and to consider what Gayatri Spivak has defined as “epistemic violence” (76), a reference to the imposition of Eurocentric cultural and intellectual frameworks that suppress, subalternise, and delegitimise alternative ways of understanding the world. This has been manifested, for instance, in the colonial appropriation of landscape depictions (as discussed by Massey “For Space”, Said, Scott, and Sluyter), which obliterate, invisibilise, and racialise the experiences and emotions that people develop in their relationship with the territory. Decolonial methods, in this regard, propose a re-historicisation towards an anti-colonial and non-Eurocentric standpoint (Mignolo xvi), hence acknowledging the experiences of domination that shape power as well as spaces.

In line with this approach, and assuming a complex notion of landscape conceived as an “event” (Massey, “Landscape as a Provocation” 46), which recognises therefore its transformative capacity as both “product and agent of change” (Aitken and Dixon 331), I suggested performing a filmic aesthetic experimentation to decolonise the border landscape in contemporary Ceuta. As part of this research process, in winter 2015, together with a group of people settled at the Temporary Stay Centre for Immigrants (CETI), we shot the experimental short film, Tout le monde aime le bord de la mer [We all love the seashore, also released under the title The Colour of the Sea for the extended cut].

In the following analysis, I explore the potential of what I define as ‘performative filmmaking,’ a collective process of making films in which people living in the represented place participate through improvised and fictionalised actions, so that their intervention constitutes a contestation of the socio-spatial order in which they are inscribed. The performative act refers here, therefore, to the transgressive capacity of artistic action to intervene in landscapes and spaces strongly connoted by political and cultural conventions, as is the case for borders, in order to overturn normative imaginaries. As I shall illustrate, the use of dramaturgical strategies that enable people to detach themselves from the identities assigned to them in these spaces will be a critical and decolonial asset for this.

The analysis draws on the methods of co-creation developed during the production of the film. I examine the dramaturgical strategies and the human and spatial relations constructed in the process. I then discuss three central aspects that may help to conceptualise performative filmmaking. First, the crisis of representation through an aesthetics of fiction to de-centre Western white-male knowledge production, which also facilitates blurring the self–other divide; second, the development of counter-spaces for self-fiction, contesting space from the perspective of migrants’ autonomy and agency; and, third, the choice of non-representational border landscapes to dislocate audiences from formal geographical conventions, as a means of also confronting dominant ways of seeing. Prior to this analysis, the following section provides an overview of critical artistic and cultural productions emerging on the Spanish–Moroccan border that help us to understand the context of audio-visual contestations and the role that they can play.

Since the early 2000s, there has been a vibrant response from artistic and activist movements to counter the media narratives that have reinforced the symbolic fortification of the Moroccan-Spanish border. Much of this work has been based on an interest in deploying new strategies of aesthetic research based on documentation and experimentation (see contributions in this regard by Barrada, Biemann, Biemann and Holmes, Fadaiat, Khalili, and Observatorio Tecnológico del Estrecho). The increase in the use of home video cameras and new portable filming technology had transformed creative processes for documenting the border but also for experiencing what the border could be. Accordingly, three lines of expression are observed in relation to political denunciation, geographical experimentation, and autobiographical exploration. The radical point to note here is that these visualisations can be interpreted as part of a critical geopolitical reading of Europe’s relations with Africa, as Chiara Brambilla has suggested for the case of Lampedusa (“Navigating the Euro/African Border” 112), insofar as they question the representational order on which political borders are based. Border documentary cinema can be read, therefore, as a reaction to evolving border dynamics, but, also, in a more emancipatory spirit, as a participation in the very transformation of border representations. In this vein, Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary (213) highlights both processes as fundamental to the artistic and cultural productions emerging from borders.

Among the films I have examined, which also serve as inspiration for the work undertaken in Tout le Monde, the border is represented as a mobile, selective, and not always visible institution. Documentaries such as España, frontera Sur (Spain, Southern Border), Los Ulises (The Ulysses), Paralelo 36 (Parallel 36), or Sahara Chronicle, portray the complexity of African mobility in relation to the evolution of EU bordering practices, so that trajectories are intertwined with the dispersion of control technologies. In Distancias (Distances), for instance, Pilar Monsell traces the signs of the externalisation process by placing the viewer in an urban district in Morocco before an identification raid that is theatricalised by immigrants, creating a montage of counterpoints with real archive images of deportations to the desert bordering Algeria. Particularly suggestive in these works is their way of showing the prolongations of the border mediated by the moving image, as well as the significance of the temporal dimension. We do not see the sites of departure or destination, only the multiple spaces/times where people meet control and immobility.

A further aspect revealed in these aesthetic-investigative border representations is the experimentation with the filmic form. One of the central axes is to make visible the mechanisms of filming and the transgression thereof. In Biemann and Sanders’ exploration of the border economy entitled EUROPLEX, the ethnographic observation is visualised through a montage in which travel diaries, interviews, and field recordings are overlaid with texts, time slots, and geographical coordinates, thus adding layers of meaning and demonstrating the artifice of editing. Other works such as Straight Stories or On Translation: Fear/Jauf dislocate the border by assuming non-narrative forms. In The Smuggler, Yto Barrada counteracts the border through the action of a woman covering her body with aprons on a black stage. This non-place setting emphasises the centrality in the subjectivity of all the women who cross the border every day carrying goods on their bodies.

In recent years, there has also been a growing interest in video diaries, which take the subjectivity of first-person testimony as an instance of enunciation and politics. Works such as Sahatain (Two Hours), Patchwork of identities or Hand-Me-Down explore identity in relation to a border that permeates the everyday, showing the asymmetrical distances in relation to family histories, sometimes reconstructing bonds, and sometimes fracturing them even further, while also representing the selective nature of mobility.

The influx of these visual expressions countering the Spanish–Moroccan/EU–African border calls for a broader understanding of the role of culture as a counter-bordering practice, and also highlights the importance of the interaction between the border and its representation (Schimanski 46). Moreover, this perspective implies interrogating non-formal modes of political agency, such as aesthetic-political interventions, encompassing the question raised by Brambilla on the strategies that could be used as emancipatory devices to yield processes of political self-empowerment “as expressions of resistance to the misrepresentation of the ‘absent agents’ determined by hegemonic understandings of global border and migration regimes” (“Exploring the Critical Potential” 29). Along these lines and taking up Henri Lefebvre’s early distinction on the dialectical relationship that exists in the triad of perceived, conceived, and lived space, it seems crucial to unveil the conditions under which the subversive can become counter-representation. The distinction between conceptualised space, which is translated into discourses, designs, and practices from lived and relational space “which the imagination seeks to change and appropriate” (Lefebvre 39), renders it a space that can be claimed by people, thereby recognising the performative potential of representation itself, as experience and experimentation are central features of the performance-based work (Haseman 100).

After a long journey from Guinea, Conakry, Aliou, Diakité, and Boubacar find themselves stranded in Ceuta. It is 2015. The waiting time at this border is uncertain and it is not regulated. The decision to transfer someone to mainland Spain can take months or even years. In the meantime, people who have crossed the border clandestinely, without an EU/Schengen visa, are placed in the CETI. This is a semi-open centre run by the Spanish government, with capacity for 512 people. The perimeter is fenced at a height of three metres with video surveillance cameras on top. It is possible to leave the centre during daylight hours by showing an identification card, the barcode of which is verified by a fingerprint. However, what becomes an actual retention space is the whole city of Ceuta. Migrants can leave the CETI, but they cannot leave the city, which they describe as a “sweet and soft prison.” During this time of forced immobility, we set out to make a film motivated by the need to escape from blockade, but also to question the performance of the border in a Butlerian sense, i.e. those “acts” by which the border is enacted and socially recognised as a border. I began the shooting of the film by asking two questions: where is the border? How do we represent it here in Ceuta? This triggered what would become the central conflict:

Julien: Do you know the future? I don’t know more than the present.

Patrice: Well, I think it is going to help migrants…

Eric: But, in the present someone can die. What is at stake? What do we gain by making this film? I am not in.

Julien: Brother, isn’t it the film that could harm us?

Patrice: But you know…

Julien: Know what?

Alhoussein: If the nation sees…

Diakite: This is not happening, eh! This doesn’t harm us.

Alhoussein: Even if this happens, listen to me… This movie will be international, everyone will be able to see it, you understand? If we talk and the great personalities can see it…

Julien: And the counterbalance? What is the counterbalance?

This conversation took place during the first day of shooting. The filming process was confronted from the outset with its direct and real political context: border control. The migratory condition of having crossed the border irregularly placed the participants on a plane of insecurity. The initial dialogue triggered by the presence of the camera, and the possibility of making the film, turned into a moment of chaos and doubt in which people discussed the consequences of their involvement, revealing how conflictive the act of filming the border can be. It could be used against people, but also to reinforce border control.

Abdoulaye: For example, I crossed the border jumping over the fence. Aliou by water and another person hidden in a car. If we say that we crossed the border by car even with all the police controls.

Diakité: No…

Abdoulaye: Let me finish. It is an example. With all the money the European Union spends to prevent us from getting in, and you go and stand in front of the camera to say that you have made it in by a route that’s supposedly illegal and--

Aliou: I don’t think…

Abdoulaye: Let me finish. If he says he entered through the checkpoint, where there is usually a lot of surveillance, I think they would be surprised, or it might even make them increase border surveillance.

Boubacar: Do you think they still have not realised? Have they not realised that there are people hiding in cars to cross the border? I do not know about them, but I’m going to do it the way I had planned. I have already found four people that will play different roles in the film.

The resolution of the conflict exposes the audiences to the real and cinematic terrain, as reality and fiction will interact during the filmmaking. Real people would perform actions to explore the border and re-signify the real scenario. The performative dimension refers here to the possibility of carrying out a practice of intervention in the real by experimenting with visual grammar and the techniques of dramaturgy and staging. Inspired by Jean Rouch’s earlier work, we resolved to blur the boundary between reality and fiction as “cinema, art of the double, represents a transition from the real world to the world of the imaginary” (Rouch cited by Henley 255). Rouch used the camera to investigate the world by activating contexts and scenarios to interact with reality; once in this setting, people improvised from elements of real life. Under this approach, fiction could function to amplify the real (Rouch 68).

And this is what we did. In the process of conceiving the film, I wrote the outline of a script that included some locations at which it might be interesting to intervene and activate improvised situations in dialogue with the landscape. It contained some elements that could function as triggers for the action. In addition, I had the intention to be attentive to unforeseen events, following a more observational documentary style. In the course of the process, we realised that fiction was crucial for performative filmmaking, as it facilitated the engagement of people under complex circumstances of control and power. We learned that people’s involvement was possible because fiction made it feasible to question the normative order in the spaces of representation. It made it easier to enliven imagination and break discursive literalness. During the shooting, there was a shared feeling that playing a role could be emancipatory in order to circumvent the limitations of living clandestinely, because the venture had nothing to do with the construction of an official truth: “there were times in the film when we didn’t think we were immigrants” (Boubacar 00:23:40).

Achieving Rouch’s commitment to fiction was possible only after a preparatory process. It began with the organisation of a cinema forum with the people sheltered at the CETI. It was intended to be a time to get together, watch films, and get out of the confinement routine. Gradually, after three months of encounters, it became a performative training space based on the acquisition of skills with the camera. The space expanded as the practice of filmic experimentation spread to different places in the city. We visited, filmed, and improvised situations in places outside the imaginary of what is permitted within the border regime, such as the commercial streets of the city centre, where migrants’ bodies remain invisible.

Politically, the cinema forum was constituted as an autonomous space outside the CETI. It was through artistic experimentation that it generated a resistance to the authoritative order of the border. Drawing on Ulrich Oslender’s work, it can be conceived as “counter-space,” as it was shaped by spatial resistance to disrupt official practices and representations of space (97). The emergence of counter-spaces is observable insofar as “the multiple resistances against today’s global neoliberal order can be seen as struggles for space” (97, translation by the author). In this direction, the notion of “counter” that Martina Tazzioli (4) emphasises in counter-mapping practices, as an analytical gaze that traces the spatial disruptions generated by migrants, was helpful as it incorporates the very challenge of the possibility of representing itself, “pushing the representational devices to their limits” (Tazzioli 6).

The recognition and activation of these counter-spaces on the border has been critical to our performative process before and during the filming. The cinema forum activated the collaborative process, as it helped to build complicity and share common understandings during the shooting. It helped to activate the mise-en-scène and influenced how the script was developed. In such an approach, we noted that locations and ideas for improvising situations are essential elements to be defined before the performance. Moreover, in the face of relevant findings, the repetition of actions several times and in different ways also proved to be enlightening, as rehearsal and fictional aesthetics have potentialities in performativity (see Tinius).

Entering the forest surrounding the city was vital to understanding that. Self-described by migrants as “el tranquilo” [“the calm”], it was silent and peaceful, away from the bustle of people and activity. It also evoked forests in other territories, awakening memories for the protagonists. But “the calm” was revealed as more than just the forest, “the calm” can also be autonomous spaces of resistance, which are mobile and shift around the forest. These counter-spaces are meeting places for sharing meals and social gatherings, in many cases organised by communities that share regions or countries of origin. “The calm” became the central counter-space for the performance, as it was a lived space that could be appropriated by the imagination, following Lefebvre’s provocation to unveil subversive acts against the normative order of space.

Stories and legends are heard here. Boubacar narrates a legend about the arrival of white settlers in Africa. Inspired by the novel Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe, he hyperbolises the arrival of the “first white man in Africa.” Most of the stories told during the filmmaking were memories of the past in which the ideas of Africa and Europe were somehow always present. Framed in this staging, and as a result of the performance, a colonial narrative emerged that linked the present nature of European border control to the initial problem of the Western colonisation of Africa. This layer of content was not conceived from the script but emerged from the dramaturgical strategy of Boubacar’s fictional play and self-fiction.

As one of the filming strategies, we decided to make the landscape a central element. The view from a location or the arrival at a new place served as a backdrop for the protagonists to converse about it. The film recorded these encounters with the aim of capturing what the presence in a particular site of the city provoked. Thus, the protagonists’ impressions and reflections on the spaces and landscapes they inhabit become a way of questioning the normative view of the border itself, sometimes de-dramatising it.

Aliou: Check out the colour of the sea. It’s different from ours.

Diakité: No, our sea also changes colour.

Boubacar: Yeah, but he’s right. There are nice beaches and seas in our country, and I haven’t seen a white sand beach here.

Aliou: There’s a beach next to the police station. The sand is white there.

Boubacar: Over there, next to the police station?

Aliou: Yeah. It has white sand. Once, when we were at the university, we climbed into some boats. That was the day I saw the beach. It’s beautiful.

Diakité: Like our beach in Bel-Air, Boffa.

In Tout le monde, the action unfolds between two landscapes, the forest and the sea, which, in their simultaneity, show the temporality of waiting in Ceuta. Each landscape sets different narrative tones, while the views of the sea, the Strait of Gibraltar, and the European shores elicited conversations about the actual present, the mundane, and the immediate; the forest enters another time in which memories of a biographical, but also an ancestral, past emerge and are transmitted. Following Doreen Massey’s reflection on the significance of the spatial montage of landscape shots in cinema, the landscape is not allowed here its soft effect, its capacity to enrapture, nor its subtle operation of reconciliation (Massey, “Landscape/space/politics”). On the contrary, the film construction bears witness to a way of understanding landscape as something imbued with temporality, understood also as a form of “dwelling perspective” premised on the active, perceptual engagement of people in the world (Ingold 152). From this reading, landscape can be re-interpreted and experienced as an active signifying practice “in which meanings are made and remade by the perceiver–observer” (dell’Agnese and Amilhat Szary 7), a perspective that also helps to understand its role in the shaping of narratives.

The founding conception of space upon which the landscape of the border rests is, therefore, punctuated by a multiplicity of stories and opened up to reinterpretation. The choice of non-representational spaces, meaning those landscapes deprived of state-visible border signs (fences, maps, flags, etc.), but also understanding the non-representational as those mundane practices that constitute the everyday (as discussed by Dewsbury, Dirksmeier and Helbrecht, and Nigel), relates to a process of geographical dislocation useful to turn the subversive into counter-representation. The dislocation of borders may function as a method to shake off the geographical numbness that cartographical borders have carved in our geographical imaginary and what Henk van Houtum and Rodrigo Bueno Lacy have named the “world’s cartographic straightjacket” (196). The dislocation consists of producing disruptions in the normative order by making coordinates and formal temporal and spatial references disappear. In the film, we do not see notices or signs telling us where we are. The CETI does not appear, nor do explicit images of migration, nor close-up shots of fences or border officers. They are not central to the image but rather are elements that trigger conversations, situations, events, or scenarios.

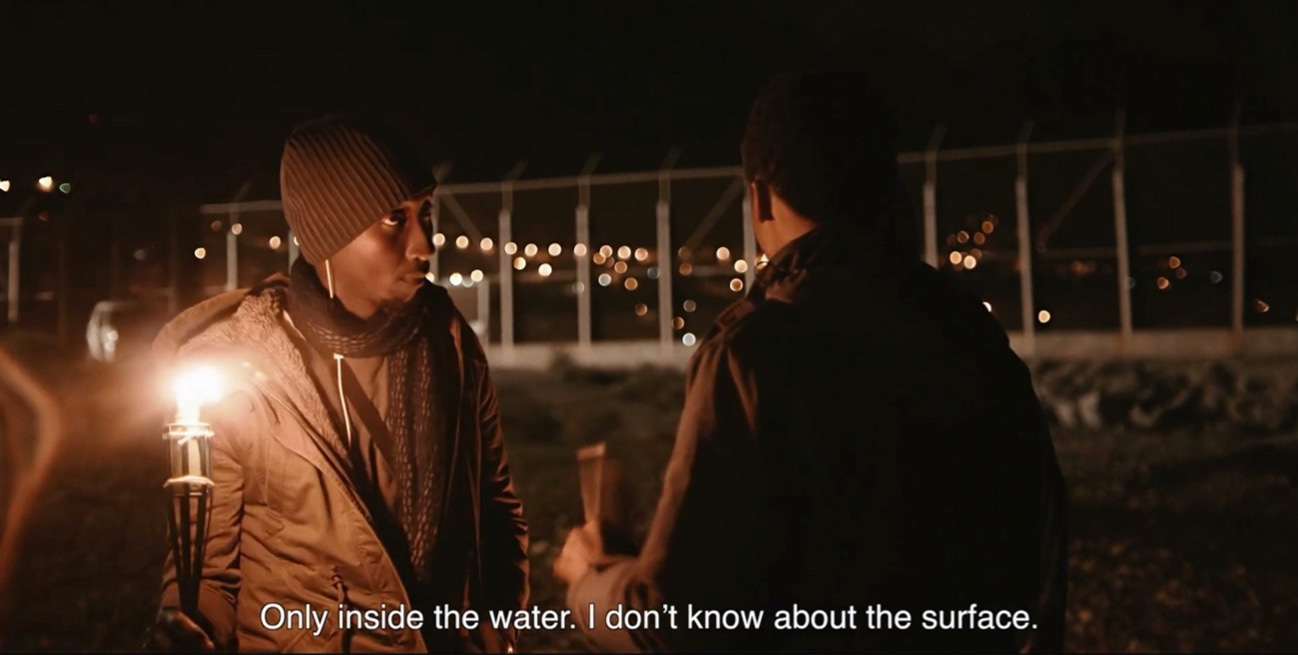

In the second sequence, for instance, the rehearsal of a surrealist screenplay is filmed, which includes a vision of a giant turtle and the possibility of making a board with it to cross the sea. The backdrop for this action is the border fence: its first and only appearance. The play takes place at night, in a dark landscape. We hear the sea. We glimpse the silhouettes of those who are now actors illuminated by torches. In the background, the overhead spotlights illuminate the fence. When the fence appears, it remains in a second plane. It is the performative act that shifts the focus to the action represented, resemanticising the position of the border fence and diverting attention from its centrality towards the subjects (figure 2). The fence is part of the landscape, but the content of the landscape is rewritten through stories.

Emma Cox and Marilena Zaroulia draw attention to the limits of performance in the face of the reality of bodies that cross borders and arrive framed in processes of death, disappearance, illegalisation, and condemnation. They question the ethical and political implications of such work even when “it appears that the need for representation, embodiment, encounter, and imagination has never been greater” (141). The authors reveal a particular kind of aesthetics that emerges from works that respond to maritime crossings or deaths at sea, and that incorporates the performative element questioning the reactions in the audiences (see also Zaroulia 181), which is produced in part by the sincerity with which the processes of creation are shown and the intentionality of political agitation in this case. The practice of performative filmmaking shares these principles. The intended intervention is to take viewers to the limits of representation and expose them to de-dramatising narratives that disrupt the normative spectacle of the border and its coloniality.

I began this contribution by pointing out that one of the challenges for a decolonial gaze would be not to reproduce the normative elements of the border in its representation. Seeking to understand how cinema can negotiate symbolic counter-spaces and offer an alternative to the media spectacle around borders, I decided to explore the potential of performative filmmaking, considering the action of filming to be a form of research in itself owing to the processes it activates in space, engaging people in the performance and through its re-signification through the experience of migration.

The project was based on various processes that are analysed in this paper. First, the recognition of the performative potential of using fiction in research processes, as a means of intervening in the real and broadening the dimensions of analysis, by involving the experience of the people taking part in the research. In this sense, participants played a role from their subjective experience and, therefore, had a degree of autonomy over what and how to narrate. This aesthetic practice can empower migrant self-representation and politically active voices against prevailing narratives, in line with a decolonial orientation. Moreover, this mode of staging, based on the activation of unforeseen situations and collective improvisations (e.g. when visiting an unknown place), proves to be an intriguing tool to delve into reality beyond what is expected or foreseeable.

Second, making visible the enunciative instances of film and using them as research tools has also illustrated the relevance that the off-screen action may play in border counter-representations. Cinema allows us to interact with presences and absences, and is therefore interesting for research that works with elements of social space, because it is an art that invites us to play with spatial correlations, the visible and the non-visible, and to disrupt the literality of images that establish a spatial regulation and order. This is one of the aspects that can be enhanced in filmic performative practices that seek to decolonise the gaze projected on borders, insofar as it emphasises the ruptures in the symbolic order, appealing to spectators to resituate themselves and think about the voids, the absences, the silences, and the invisibilisation that comprise all representation. In this sense, what is absent in the image or outside the frame is in fact a stimulating device that is set in motion through the performative as a critical methodology of experimentation with the representational space, transgressing it and revealing its subjective charge.

Furthermore, and particularly relevant to the study of borders, we find spatial dislocation to be a method coherent with the decolonial approach insofar as it proposes a radical delocalisation on the subject to create a new symbolic order. In our performative act, dislocation operates through the choice of non-representational border landscapes. Thus, landscapes in the forest and at sea, devoid of political signs, but not politically neutral, have been unveiled to make possible the emergence of alternative narratives that speak to the colonial dimension of the border, and the racialisation and selection that operate on mobility in this geography.

During this process, the creation of counter-spaces defined by resistance, like the cinema forum or “the calm” in the woods, activated a relational context that allowed strategies of representational re-appropriation to unfold. Landscapes become narratives precisely through the collaborative process that motivates this performance. In this case, the commitment to developing an open script, in dialogue and mixed with improvisations, allowed us to enter territories that would otherwise have been ignored, and it is also through this process that we attempted to blur the self–other divide, acknowledging the mediating instances of the performance itself. It is all these layers of the performative process that lead me to conclude that cinema can potentially articulate resistances by creating alternative border aesthetics.

The documentary was produced in the framework of the research project "Borders, Political Landscapes and Social Spaces: Potentials and Challenges of Evolving Border Concepts in a post-Cold War World" (FP7-SSH-2011-1-290775, EUBORDERSCAPES), funded by the European Commission under the FP7 Programme.

Achebe, Chinua. Things Fall Apart. Anchor Books, 1994 [1958].

Aitken, Stuart C., and Deborah P. Dixon. “Imagining Geographies of Film.” Erdkunde. Vol. 60, 2006, 326–336, https://doi.org/10.3112/erdkunde.2006.04.03

Amilhat Szary, Anne-Laure. “Walls and Border Art: The Politics of Art Display.” Journal of Borderland Studies. Vol. 27, No. 2, 2012, 213–228, https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2012.687216

Aris Escarcena, Juan Pablo. “Ceuta: The Humanitarian and the Fortress EUrope.” Antipode. Vol. 54, No. 1, 2022, 64–85, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12758

Barrada, Yto. Yto Barrada. JRP/Ringier, 2011.

Bialasiewicz, Luiza. “Off-shoring and Out-sourcing the Borders of EUrope: Libya and EU Border Work in the Mediterranean.” Geopolitics. Vol. 17, No. 4, 2012, 843–866, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2012.660579

Biemann, Ursula, and Brian Holmes, eds. The Maghreb Connection. Movements of Life Across North Africa. Actar, 2006.

Biemann, Ursula. Mission Reports. Artistic Practice in the Field - Ursula Biemann Video Works 1998-2008. Cornerhouse Publishers, 2008.

Binimelis-Adell, Mar, and Amarela Varela Huerta, eds. Espectáculo de Frontera y Contranarrativas Audiovisuales. Estudios de Caso Sobre la (auto)representación de Personas Migrantes en los dos Lados del Atlántico. Peter Lang, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3726/b16808

Brambilla, Chiara. “Navigating the Euro/African Border and Migration Nexus through the Borderscapes Lens: Insights from the LampedusaInFestival.” Borderscaping: Imaginations and Practices of Border Making, edited by C. Brambilla, J. Laine, J. Scott, and G. Bocchi, Ashgate, 2015, 111–122. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315569765

–––. “Exploring the Critical Potential of the Borderscapes Concept.” Geopolitics. Vol. 20, No. 1, 2015, 14–34, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884561

Butler, Judith. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal. Vol. 40, No. 4, 1988, 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893

Campesi, Giuseppe. “Seeking Asylum in Times of Crisis: Reception, Confinement, and Detention at Europe’s Southern Border.” Refugee Survey Quarterly. Vol. 37, No. 1, 2018, 44–70, https://doi.org/10.1093/rsq/hdx016

Cox, Emma, and Marilena Zaroulia. “Mare Nostrum, or On Water Matters.” Performance Research. Vol. 21, No. 2, 2016, 141–149, https://doi.org/10.1080/13528165.2016.1175724

dell’Agnese, Elena, and Anne-Laure Amilhat Szary. “Borderscapes: From Border Landscapes to Border Aesthetics.” Geopolitics. Vol. 20, No. 1, 2015, 4–13, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2015.1014284

De Genova, Nicholas. “Spectacles of Migrant ‘Illegality’: The Scene of Exclusion, the Obscene of Inclusion.” Ethnic and Racial Studies. Vol. 36, No. 7, 2013, 1180–1198, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2013.783710

Dewsbury, John-David. “Non-representational Landscapes and the Performative Affective Forces of Habit: From ‘Live’ to ‘Blank’.” Cultural Geographies. Vol. 22, No. 1, 2014, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474474014561575

Dirksmeier, Peter, and Ilse Helbrecht. “Time, Non-representational Theory and the ‘Performative Turn’—Towards a New Methodology in Qualitative Social Research.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung, Vol. 9, No. 2, 2008, Art. 55.

Distancias. Directed by Pilar Monsell, Estudi Playtime, 2008.

España, frontera sur. Directed by Javier Bauluz, Crear Cultural, 2000.

EUROPLEX. Directed by Ursula Biemann and Angela Sanders, self-produced, 2003.

Fadaiat. Fadaiat: libertad de movimiento + libertad de conocimiento. Aire incondicional, 2006.

Fernández-Molina, Irene, and Miguel Hernando De Larramendi. “Migration diplomacy in a de facto destination country: Morocco’s new intermestic migration policy and international socialization by/with the EU.” Mediterranean Politics. Vol. 27, No. 2, 2022, 212–235, https://doi.org/10.1080/13629395.2020.1758449

Ferrer-Gallardo, Xavier, and Keina Espiñeira. “Immobilized Between Two EU Thresholds: Suspended Trajectories of Sub-Saharan Migrants in the Limboscape of Ceuta.” Mobility and Migration Choices. Thresholds to Crossing Borders, edited by Martin Van der Velde and Ton Van Naerssen, Routledge, 2016, 251–263.

Garelli, Glenda, Charles Heller, Lorenzo Pezzani, and Martina Tazzioli. “Shifting Bordering and Rescue Practices in the Central Mediterranean Sea, October 2013–October 2015.” Antipode. Vol. 50, No. 3, 2018, 813–821, https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12371

Gross-Wyrtzen, Leslie, and Lorena Gazzotti. “Telling histories of the present: postcolonial perspectives on Moroccoʼs ‘radically newʼ migration policy.” The Journal of North African Studies. Vol. 26, No. 5, 2021, 827–843, https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2020.1800204

Hand-Me-Downs. Directed by Yto Barrada, Yto Barrada, 2011.

Haseman, Brad. “A Manifesto for Performative Research.” Media International Australia. Vol. 118, No. 1, 2006, 98–106, https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X0611800113

Henley, Paul. The Adventure of the Real: Jean Rouch and the Craft of Ethnographic Cinema. University of Chicago Press, 2009. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226327167.001.0001

Ingold, Tim. “The Temporality of Landscape.” World Archeology. Vol. 25, No. 2, 1993, 152–174, https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.1993.9980235

Javourez, Guillame, Laurence Pillant, and Pierre Sintès. “Les frontières de la Grèce: un laboratoire pour l’Europe?” L’espace Politique. Vol. 33, No. 3, 2017, https://doi.org/10.4000/espacepolitique.4432

Khalili, Bouchra. Story Mapping. Bureau des compétences et désirs, 2010.

Lefebvre, Henri. The Production of Space. Blackwell Publishing, 2007 [1974].

Los Ulises. Directed by Agatha Maciaszek and Alberto García Ortiz, Artika Films, 2011.

Massey, Doreen. For Space. SAGE Publications, 2005.

–––. “Landscape as a Provocation: Reflections on Moving Mountains.” Journal of Material Culture. Vol. 11, No. 1–2, 2006, https://doi.org/10.1177/1359183506062991

–––. “Landscape/space/politics: An Essay.” The Future of Landscape and the Moving Image, 2011. Accessible at: https://thefutureoflandscape.wordpress.com/landscapespacepolitics-an-essay/

Mignolo, Walter. The Politics of Decolonial Investigations. Duke University Press, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781478002574

Observatorio Tecnológico del Estrecho. “Madiaq Territory. New Geographies.” The Maghreb Connection. Movements of Life across North Africa, edited by Ursula Biemman and Brian Holmes, Actar, 2006, 175–181.

On Translation: Miedo/Jauf. Directed by Antoni Muntadas, BNV Producciones, 2007.

Oslender, Ulrich. “La búsqueda de un contra-espacio ¿hacia territorialidades alternativas o cooptación por el poder dominante.” Geopolítica(s): revista de estudios sobre espacio y poder. Vol. 1, No. 1, 2010, 95–114.

Paralelo 36. Directed by Jose Luis Tirado, ZAP Producciones, 2004.

Patchwork of Identities. Directed by Abdel-Mohcine Nakari, self-produced, 2009.

Rouch, Jean. “La caméra et les hommes.” Pour une Anthropologie Visuelle, edited by Claudine De France, Éditions Mouton, 1973, 53–71. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110807400-004

Sahara Chronicle. Directed by Ursula Biemann, Ursula Biemann, 2007.

Sahatain. Directed by Karim Aitouna, Haut les Mains Productions, 2008.

Said, Edward. Orientalism. Vintage Books, 1979.

Schimanski, Johan. “Border Aesthetics and Cultural Distancing.” Geopolitics. Vol. 20, No. 1, 2014, 35–55, https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.884562

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Yale University Press, 1998.

Sluyter, Andrew. Colonialism and Landscape: Postcolonial Theory and Applications. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2002.

Spivak, Gayatri C. “Can the Subaltern Speak?” Colonial Discourse and Post-colonial Theory: A Reader, edited by Patrick Williams and Laura Chrisman, Columbia University Press, 1994 [1988], 66–111.

Straight Stories – Part 1. Directed by Bouchra Khalili, Bouchra Khalili, 2006.

Tazzioli, Martina. “Which Europe? Migrants’ uneven geographies and counter-mapping at the limits of representation.” Movements. Journal für kritische Migrations-und Grenzregimeforschung. Vol. 1, No. 2, 2015.

The Smuggler. Directed by Yto Barrada, Yto Barrada, 2006.

Thrift, Nigel. Non-representational Theory: Space, Politics, Affect. Routledge, 2008. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203946565

Tinius, Jonas. “Capacity for Character: Fiction, Ethics and the Anthropology of Conduct.” Social Anthropology. Vol. 26, No. 3, 2018, 345–360, https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-8676.12531

Tout le monde aime le bord de la mer. Directed by Keina Espiñeira, El Viaje Films, 2016.

van Houtum, Henk, and Rodrigo Bueno Lacy. “The Migration Map Trap. On the Invasion Arrows in the Cartography of Migration.” Mobilities. Vol. 15, No. 2, 2020, 196–219, https://doi.org/10.1080/17450101.2019.1676031

Zaroulia, Marilena. “Performing that which Exceeds Us: Aesthetics of Sincerity and Obscenity During ‘The Refugee Crisis’.” Research in Drama Education: The Journal of Applied Theatre and Performance. Vol. 23, No. 2, 2018, 179–192, https://doi.org/10.1080/13569783.2018.1439735