Immersion is a metaphorical term derived from the physical experience of being submerged in water. We seek the same feeling from a psychologically immersive experience that we do from a plunge in the ocean or swimming pool: the sensation of being surrounded by a completely other reality, [. . .] in a participatory medium, immersion implies learning to swim, to do the things that the new environment makes possible. (Janet Murray, Hamlet on the Holodeck 98-99, emphasis in original)

Immersion has become both a powerful metaphor and a branding strategy for a wide range of contemporary participatory performance practices. In its current usage, immersion is used in a variety of disciplinary contexts, ranging from musical performance to site-specific theatres and computer gaming. This interaction between performing arts and digital technology is also at the heart of our collaborative practice-based research project Playing with Virtual Realities (PwVR), an interdisciplinary exploration of immersion by computer scientists, designers, philosophers, choreographer, dancers, and dramaturgs in experimenting with cognition, embodiment, and VR-technology. In this article we re-stage our collaboration as a series of interventions and interferences into each other’s practices and knowledge bases. In doing so, we would like to propose that immersion is not only the focus of this performance research project but also illuminates the process of collaboration itself. If we define immersion with Janet Murray above as “learning to swim” in a different reality, as integrating performers and spectators in a single environment, a similar process occurs in the act of collaborating across disciplines: a plunge into one another’s languages and knowledge practices. This never amounts to a fusion into a single stable environment shared by everyone involved but rather constitutes multiple passages between alternate realities. In our collaboration the exchange between different collaborators becomes one of interference and interruption, echoing Paul Carter who describes collaboration as a form of material thinking that is a struggle: “collaboration is, first of all, an act of dismemberment” as well as, secondly, “an art of placing” (11) that also translates into the performance. This sense of interference and cross-disciplinary transfer translated into a cross-medial transfer in the project itself: a struggle between the performative embodiment provided by the dancing bodies and the virtual environment conjured up through VR technology. Virtual and actual worlds both interfered with and extended each other.

PwVR consisted of three parts: an interdisciplinary workshop on how to explore VR through dance; a one-day symposium on virtual reality with scholars and practitioners from gaming, media design, choreography, philosophy, and performance studies; and finally, a dance performance that staged the interaction between the dancing bodies and virtual environments. The process of creating the VR/dance performance will be our focus here. PwVR was first performed by two dancers with one set of VR goggles (a tech team of two coordinated the VR-applications) at Dock 11 in Berlin in January 2018 — watch here.

In our performance, the dancers explored various virtual environments with the help of VR goggles while live spectators were seeing the dance space in front of them plus a projected 2D version of the VR space on a screen behind the dancers. The focus was on the cross-medial encounter of the body and VR. A prologue aimed at acquainting a lay audience with the parameters of VR-technology: the dancers taped the boundaries of the virtual playing space onto the physical stage while a computer-generated voice-over provided some ground rules. The fundamental premise of the performance was to have dancing occur across virtual and actual spaces, i.e., the dancers took turns dancing “inside” and “outside” of VR while maintaining a connection to each other. In the following four different scenes, the dancers moved within different VR applications: “Space Pirate Trainer,” a spatial arcade shooting game; “Lone Echo,” a VR adventure game, and “Tilt Brush” plus “Masterpiece VR,” three-dimensional drawing applications. Throughout, a common soundscape allowed spectators and dancers to share an aural space while their visual sphere (in- versus outside the VR) remained radically different. In the closing scene, the separation between spectators and performers gradually disappeared, and everyone joined into a dance party finale. Ultimately, the performance was an exercise in interruptions, using dance performance and VR technology as foils for one another to show up their differing techniques of immersion. The immersivity of VR-technology is based on the overwhelming visual absorption it offers: the user is plunged into a 360–degree alternate experience that is immensely absorbing and generates physiological responses to the illusions of depth and space. This form of mental immersion was disrupted and extended by the live interventions of dancing bodies that performed on stage and in the VR environment at the same time. In effect, the project put the apparatus of VR technology on display to ask: what happens to the body in VR?

Throughout, investigating immersion offered a shared focus for our work. We found immersion not to be a singular process of embeddedness but rather a fluctuation between moments of embeddedness that necessarily implied moments of interruption: a movement between proximity and distance. This echoes Josephine Machon’s assessment of immersion as a layered process of differing intensities, ranging from “absorption” to “total immersion” based on a world-building that includes the agency of the spectator (63). However, PwVR treads new ground in allowing two different notions of immersion — VR’s technological immersion and embodied immersion — to encounter each other. Immersion turns into a movement of multiplicity that focuses on the transition between different realities, much as our collaboration across various disciplines was such a process of transitioning between forms of cognition, knowledge, and making. In order to capture the idea of collaboration as transitioning, we developed a set of framing encounters during the rehearsals; they allowed us to move between environments and between our different disciplinary perspectives. We therefore choose to offer this article as a conversational chain letter between five co-collaborators, re-creating one of our most fundamental rehearsal practices: interviewing each other as a constitutive part of our process to bring together the often very different cognitive experiences in- and outside of VR. These interviews highlighted the different disciplinary languages we were speaking as performers, philosophers, gamers, designers, and dramaturgs and allowed us to mediate between them and build joint experiences and common vocabularies. To become surrounded by and to immerse ourselves into our respective perspectives we needed to interrupt and intervene. In the following dialogical interventions, we would like to give you an experience of our collaborative practice.

Ramona Mosse (RM, dramaturg/theatre scholar): VR-technology promises a seemingly endless alternate world up for exploration, and yet it has clear borders and limits that usually remain invisible but that we — for the purposes of our performance project — made manifest in the performance. I would like to think of our technique as one of immersion across borders. Christian, what do you make of the notion of immersion as a perpetual process of transitioning?

Christian Stein (CS, game design/computer scientist): In game theory we talk about the magic circle of the game: “To play a game means entering into a magic circle, or perhaps creating one as a game begins” (Tekinbas and Zimmerman 95) which echoes the theatrical stage as offering a fictive world with its own rules of engagement. In this sense, immersion cannot be thought without the transgression of a border between differing spaces. Experiencing the inside of a virtual space requires one such border crossing. At the same time, these crossings are also shifting the border, taking something into the game from the outside and vice versa: the creation of the magic circle! In this sense, immersion is not a state of mind, it is a process of an interface. Einav, the interface of a performer in this project multiplied to one between mind and body and between body and technology. How did these interfaces interact from a performance perspective?

Einav Katan-Schmid (EKS, director/choreographer): Dancing is an artistic activity. The act of moving does not only relate the space and the world around us but also brings another world — an imaginary one — to life (Valéry 1976). To follow Paul Valéry’s philosophy of the dance, in dance (and the performing arts generally) we deal with a world of “make believe” and generate a continuity between the actual space as we perceive it and an image of another spatiality that we embody. The principles of the “other spatiality” created by dancing supplement immediate reality. In order to move elegantly, we have to play the act of as if — meaning, to move in an invented spatiality and — to generate a felt experience of what is invisible. For Merleau-Ponty, for instance, motility and spatiality are activities of taking hold within the world as we physically inhabit it; in dancing we move also another layer of spatiality, which we imagine, create, and generate (Merleau-Ponty 145, 112-171; Katan 43-85). Usually, the “other spatiality” is conducted by incorporated rules of games, a score, instructions, or a technique. Let us take Forsythe’s CD-ROM publication, Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye, as an example. Here, Forsythe physically demonstrates a score that formulates a set of rules for his movement technique. In the CD-ROM publication this set of rules is made visible through annotations (white lines and shapes tracing his movements) and reveals the precision of bodily movements that follow the imaginary rules rendered by his technique (Forsythe and Haffner). Dancers bring life into a spatial game — they move as if there is an inner logic that motivates the dance, while in practice, they follow a pre-trained score, a technique, or an instruction. When the game of “make believe” is successful, we tend to experience it as presence: the dancers generate a real sensation of the score or the images they follow. Alva Noe defines the feelings of presence — “they experience the world in time” (74-81) — as enacting imaginary content within a felt sensation. As a dancer, when I achieve sensation within perception, it means that I do not chase after the instruction of the dance, I rather feel it. I would like us, therefore, to think of immersion in terms of performative presence.

Nitsan and Lisanne, what helps you in generating presence when dancing? How did that change in our project?

Nitsan Margaliot (NM, dancer/choreographer): In principle, one cannot teach presence in dance. It is a state of mind: a certain totality, a being in the here and now, generating this cross-over between time and space to invite an audience in to a dance performance. PwVR was the first time I dived into the VR world. Being unfamiliar with the term “immersive” beforehand, I did not expect how addictive I would find the experience. While inside the VR headset, both Lisanne and I were busy navigating between the virtual and physical worlds: we had to create a “negotiated presence.” That implied an added complexity: we had to embody both a perceived virtual world and a felt actual world and transmit the combined experience to an outside audience. In this case, the gap between the spectators and my embodied experience felt larger than usual, so it helped me to engage with the VR and care less about the spectators. How did you generate presence in those circumstances, Lisanne?

Lisanne Goodhue (LG, dancer/choreographer): I was extremely busy connecting to the actual physical world surrounding me, in order to counterbalance the lack of “sensing” an audience whilst in the VR. For example, touching the cable, and feeling tension on the cable of the headset helped me to orientate myself (I unplugged it many times by accident): it indicated to me the location of the computer and hence the audience. My attention was constantly shifting between the VR images and concrete sensations onto which I rely to generate my dancing: the weight of the headset, feeling my hands clapping on the floor. My sense of touch was heightened to keep me grounded. It is through this concrete physical information that I knew I could really connect and be present with the audience: by addressing a “sense of reality” that they also belonged to. Sabiha, how did you as a game and experience designer contribute to PwVR?

Sabiha Ghellal (SG, game design): As an experience and game designer, I am concerned with the question of how to create meaningful experiences. Vyas and Van der Veer (2006) regard meanings as interpretations that experiencers construct during their interaction with or through an interactive system. According to Umberto Eco (1979), openness to experience and interpretation is a fundamental part of perception; the experiencer observes and interprets but essentially never exhausts a work’s possibilities. For artistic creation, the artist’s role, in this case the dancers, is to start a work; it is the role for the spectators to finish it. The completed work, which exists after the interpretation of the spectator, still belongs to the artist in a sense but must also belong to the viewer. Meaningful mixed reality (MR) experiences address subjective perception. Experience Design, in contrast to usability, focuses on subjectivity, i.e., the individually perceived quality of a product. The subjective nature of MR experiences leads to a very individual experience that can only be designed to a certain degree. The philosophical tradition of constructivism assumes that a recognized object is construed through the process of recognition, and here lies the challenge or the tension when designing MR experiences. MR thrives on discourse and subjective fantasy, the world of the viewers or dancers, regardless of how much interaction (cognitive and physical) is required of both groups. Ultimately, it is always a matter of the importance each person attaches to the experience, and whether it personally enables the experiencer (dancer or audience) to see or even feel the virtual, in our case the traces of specific dance moves (through the projected VR world on stage). In PwVR, we were exploring how embodied and virtual practices could combine to create new experiences. My core motivation for participating in the interdisciplinary research was to explore how much movement is possible while still staying “present” in virtual environments. As such, my primary focus was the “lived experiences” (Van Manen 2016) of the dancers. The resulting experience of the spectators, which I would describe as a special form of an augmented experience only became important during the production of the final performance.

RM: From a theatrical perspective, PwVR extended the experience of theatrical performance as a combination of imaginary and architectural spaces by a competing virtual environment in VR. Through the multiplication of virtual worlds, the transition between them became the core of the aesthetic experience. Nitsan’s and Lisanne’s lived experience turned into a dramaturgical bridge between the virtual sphere the audience was set apart from and the promise of an immersive performance that could integrate these different spheres. Overall, immersive and self-reflexive moments alternated throughout the performance. The spectators’ experience of the performance event was fundamentally discontinuous. PwVR ultimately addressed this ambiguity of immersive experiences. Oliver Grau defines immersion as “a passage from one mental state to another […] characterized by diminishing critical distance to what is shown and increasing emotional involvement in what is happening” (13). He identifies the potential of and problem with immersion that makes for its ambiguity: the intensity of emotional involvement that immersion promises also suggests a loss of control in terms of judgment, be it moral or critical. Our goal was not just to create a VR experience but to put VR-technology on display; with one dancer in and one outside the VR we put the difference between these different worlds centerstage. The VR dislocates the embodied performance of the dancers, while the staging of their VR-experience dislocates the spectators’ perception of virtuality as such. Ultimately, PwVR does not privilege one form of knowledge acquisition over another: the question is not one of self-reflexivity versus immersion. Instead, the experiment is focused on the border between perceptual and cognitive regimens themselves and privileges the creative as well as critical potential of such a discontinuous experience.

CS: Such a mix of limit and potential also becomes important when tying Nitsan and Lisanne’s dance moves back to the gaming context. Gamers and dancers share that their bodies display a high degree of control, precision, and expressivity. Yet, there are also crucial differences. Gamers generally do not aim to express anything beyond the game itself. Goal orientation governs how they interact with the game. Nevertheless, each game creates a different set of movements in response to the stimuli of the virtual environment. In contrast, the dancer’s interior mental images generate physical movement. These movements are an expression rather than a reaction. In joining these perspectives, our project opened an experimental liminal space for gamers and dancers. This experience allowed dancers to understand their movements in terms of control, i.e., directly influencing a digital environment that provided instant feedback. In turn, gamers had the chance to experience their movements as not only goal-oriented in digital space but as an expression in their own right, perceivable by an audience. We aimed to create a mutual understanding for the distinct scores and motivations that gamers and dancers employ. These experiments are important, since the technology is in a phase of massive expansion as new applications move beyond the traditional gaming structures to create new unique experiences instead. With the body at the center of VR, we can expect that the dancer’s movement knowledge will serve as a crucial element in future developments for VR.

EKS: To explore movement and the digital space, I read the immersion of the dancers in virtual reality as perceptual embodiment (Jarvis 2019). For the perceptual process in dance, I would like us to build on the definition of aesthetic experience by American pragmatist John Dewey. For Dewey, an artistic experience is a perceptual work of doing and undergoing (46). Let’s apply Dewey’s definition to a dancer’s perceptual work: while dancing I generate an image and simultaneously explore sensual qualities that give me further input for realizing the image through my movements. Thus, the perceptual experience of dancing is leading a gesture and feeling it at the same time. Dancing is about a mental commitment as much as a physical effort: I need to be present and attune my imagination and sensibility. Dancing is a labour of bringing an image to life. Following Gaga movement language, developed by the choreographer Ohad Naharin (Katan 2016), I use “relating metaphors” as a method for leading the dancers and asking for their physical and perceptual embodiment. I borrow here the notion of metaphors, as it is used in philosophies of embodied cognition and enactivism (Lakoff and Johnson 1980; Gallagher and Lindgern 2015). Accordingly, the comprehension of abstract notions (in our case the digital signs, or score) is further comprehended through a full body engagement and throughout the enactive experience of bringing spatiality into a felt — meaningful — understanding. In our project, we needed to synthesize information from the VR technology with the metaphorical instructions that were part of the dance. Digital signs became instructions, which the dancers needed to embody a concrete and felt physical sensation. Sabiha, how did you enter into the workshop as an Experience and Game Designer? Can you talk about the practical methods that assisted you in interacting with dance instructions?

SG: One of the main challenges of this research project was rooted in its interdisciplinary nature and the plethora of available theoretical concepts to draw on. Selecting and focusing on a limited number of concepts such as presence (Minsky 1980; Sheridan 1992; Held and N. I. Durlach 1992; Calleja 2011), immersion (Slater and Wilbur 1997; Sherman and Craig 2003; Murray, 1997; Stanney 2002) and metaphors (Csikszentmihalyi 1990; Norman 2013; Indurkhya, 1992.) helped to focus this research.

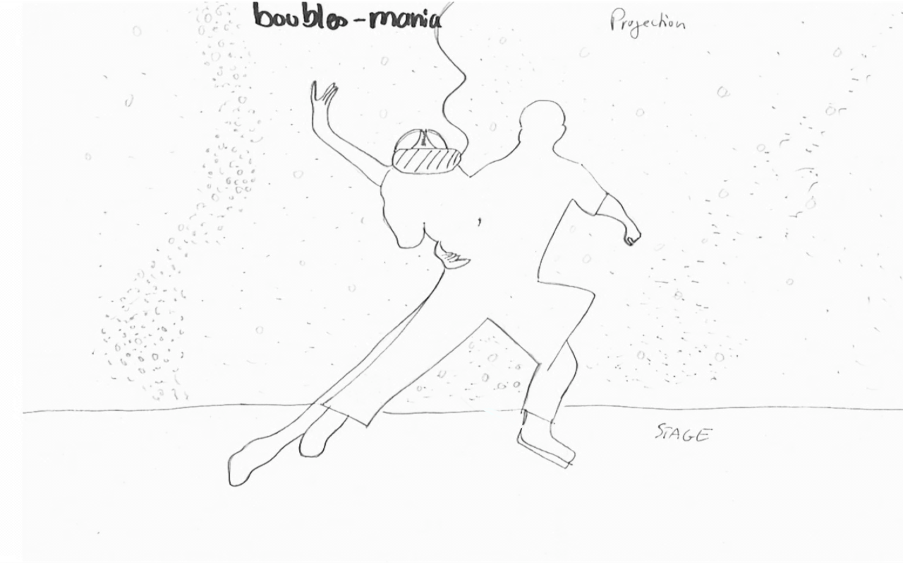

During the workshop the role of metaphors in the various disciplines became a core point of discussion. Experience or game designers often scribble ideas in order to explain an experience in form of a visual metaphor. Figure 3 illustrates a scribbled interdisciplinary metaphor that resulted in an elaborate dance instruction.

The “bubbles”-environment the dancers created in the last scene using “Tilt Brush” was projected on the stage to make the virtual world visible for the audience. Figure 4 illustrates how the interdisciplinary metaphor created a holistic experience that merged dance instructions with visual and aural metaphors.

RM: To add to that: The bubbles metaphor extended further and enabled our collaboration to integrate experience design, choreographic instruction, virtual world and dancing bodies in the final “Tilt Brush” scene. The metaphor of dancing bubbles generated the visual bubbles in the virtual world. In turn, soap bubbles blown into the actual stage space marked the collapsing borders between the multiple stages of PwVR and opened the performance into the concluding dance party, in which the spectators were invited onstage. The visual metaphors of bubbles turned into a crucial dramaturgical devise for the performance.

SG: That leads me to a question to Einav: as an experience/game designer I work a lot with visual metaphors and mental models in order to provoke certain reactions or explain systems directly to a player. How do you use metaphors in your research and dance practice?

EKS: The choreographic composition had two core tasks: first, to organize the engagement of the dancers; second, to guide the aesthetic process of engagement for the spectators as an unfolding of meaning in time. At first, the virtual and physical worlds appeared to be separate and competitive realms for the dancers. As a consequence, the relationship between them also remained unclear to the spectators. In response, the focus of the choreography shifted to manifest the relationship between the virtual and the physical. The virtual images illustrated the metaphoric source for movement and interaction to the dancers. The final bubbles scene may serve as an example: when Lisanne designs the virtual space with bubbles, she is also working with the sensual metaphor of bubbles running through her body. The metaphoric instruction informs her physicality throughout the scene and gives precise information that Lisanne needs to realize. The sketches within the VR guided the movement in the physical space and provided haptic impressions that the dancers sensually embodied. This solution had a double effect: firstly, the metaphoric instruction gave the dancers a concrete task with which to connect the visual and physical spheres; secondly, the virtual image doubled the dancers’ imagination. It created the impression as if the dancers physically responded to what they saw.

The metaphoric image also resolved the difficulties of mediating a three-dimensional world by way of a two-dimensional screen. We projected the perspective of the dancers in VR on the back wall for the spectators. Associating the screened images with the bodily feelings of the dancers enriched the mediated experience. The image becomes a partial utterance, inviting the spectator to decipher and connect them to the other staged happenings. The emphasis on correlations and their active interpretation by the spectators became an artistic statement about communication. After all, when we communicate, our articulations and expressions often lack the full dimensions of our experiences. Lakoff and Johnson address this challenge in their concept of the image-schema. Accordingly, individuals have richer embodied feelings of concepts and ideas than what these ideas denote or designate in abstraction (Lakoff 1987; Johnson 1987). The screened two-dimensional image of the dancer’s gaze in the VR literalized this challenge. The strength of mediating images lies in their capacity to trigger, enrich, and move the imagination and understanding of others. Lisanne, how did metaphors influence your personal experience during the performance?

LG: As a dancer, I work on heightened bodily awareness in order to relate to my surroundings: the drop of sweat rolling down my cheek, the hardness of the floor resonating in my joints, etc. I lost touch with this information at times when drifting in the imagery of the VR. I felt I was losing my sense of self and could not track what was happening around me. At times, I related to the VR apparatus metaphorically. At one point, I used the cable of the headset as a whip, for example. Integrating the apparatus into my own imaginary world provided another crucial connection between the worlds.

Immersion occurred when I finely balanced moments of activity and passivity. Making active choices allowed me to exert influence on a pre-designed situation. I started to design my choices inside and outside the VR to be more engaged: at times, I chose to close my eyes inside the VR, for example, or I worked with a given sensual dance instruction, such as “fill up your body with bubbles.” I could then decide how I wanted to navigate my dance experience within the VR application. In general, I had to abandon my first impulse of separating the physical and VR worlds, as this tendency generated confusion rather than engagement. I merged both worlds into one and used sensory stimuli and my imagination in order to enact my dance.

CS: Interaction choices provided by the off-the-shelf VR applications we picked (“Space Pirate Trainer” and “Tilt Brush”) strongly affected the overall experience. Sabiha, how would you analyze the two different ways of interaction that the performance was experimenting with?

SG: Experience design focuses on the subjective nature of “lived experiences” (Van Manen 2016) which can be defined as the knowledge an experiencer gains through direct, first-hand involvement with a system. In previous research (Ghellal 2017), I differentiated between “ambiguous” (Gaver, Beaver, and Benford 2003) and “prescribed” qualities when designing an interactive system. Ambiguous qualities become privileged in designs that evoke creativity, critical thinking, contemplation, and complex interaction responses in the participant. Gaver et al. further describe ambiguity as a resource for design and state that “ambiguity sometimes arises not because things are themselves unclear, but because they may be understood in different contexts, each suggesting different meanings” (Gaver et al. 223). One of the examples provided by Gaver is the collaborative, mixed reality game “Desert Rain” by the artist group Blast Theory. “Desert Rain,” which has been touring since 1999, was designed for six players. Standing on a footplate and zipped into a booth, each of the team members explored an abstract virtual world projected onto a screen of falling water in front of them. The players had 30 minutes to get to the final room, where other players they encounter might have a very different interpretation of the MR experience (Koleva et al. 2001). In contrast, prescribed qualities give clear instructions on how to interact with a system, and explain a setting or portray a particular perspective on a given subject. I would suggest that our interdisciplinary research illustrated that VR applications that stipulate one type of interaction through a more “prescribed” type of interaction, are harder to integrate into a dance performance since the preliminary focus of the interaction may not be suitable for other desired dance, physical or audio-visual metaphors. Limited interaction choices — in the case of “Space Pirate Trainer,” dodging laser attacks and attacking droids — may limit the dance score and expressivity. More ambiguous and playful interactions within a VR application such as “Tilt Brush” allow the dancer to primarily focus on dancing. Here the interactive role of the dancer through painting the virtual space, is only the secondary interaction because the different “brush strokes” offered by the application allow for psychological, emotional, hermeneutic, or semiotic dance interpretations. The dancers were able to visualize dance “traces” by holding the controller while dancing and created a painting or visualization of his or her “dance traces” (Figure 5).

A question to Nitsan: you performed as a VR dancer in both: a more ambiguous experience in “Tilt Brush” and a more prescribed experience in “Space Pirate Trainer.” How would you contrast the two experiences?

NM: During my first attempt in “Tilt Brush,” I was excited to trace my movements. I made movements and could engage with them as a three-dimensional trace in space: I literally moved my body around the lines. I confronted a new unfamiliar feeling in dancing: while my vision was occupied by the virtual image, I could feel but no longer see my body. While “Tilt Brush” allowed for a high degree of creative freedom, the arcade game “Space Pirate Trainer” felt different. When playing “Space Pirate Trainer,” I got used to set patterns of playing the game as if the applications imprisoned me in my mobility. Throughout the rehearsal process we questioned the limits of immersion, emotionally as well as mentally. In one scene I was rapping, while playing “Space Pirate Trainer.” I attempted both: to perform and to simultaneously win the game. Here, I had to learn how to coordinate and to conduct two separate wills, so as not to break the rules and to continue embodying the rehearsed score.

EKS: The challenge of working with ready-made VR applications was how to redesign their experience to provide enough room for the dancers to interact with them expressively. As Sabiha mentioned when referring to Eco’s open work (1979) — I wanted the experience we offer the viewer to be open for interpretation. In “Space Pirate Trainer,” the dancers responded to events in the game world. The game instructions — defending oneself against and destroying spaceships — could accelerate the precision of how and where to move. Since we decided not to project the content of the VR on screen in this part of the scene, the gamer’s activity appears as if they were choreographed gestures to the spectators instead of prescribed responses to “Space Pirate Trainer.” When Nitsan and Lisanne had played with “Space Pirate Trainer” during rehearsals, projecting the game on a screen lacked expressive tension. The reactive movements of Lisanne and Nitsan were too anticipated and without dramatic suspense and failed to communicate beyond the immediate constraints of the game. We had to layer the motivations for movements and combine our mental and virtual images in order to create meaningful and affecting aesthetic expressions. As Sabiha suggested, the experience of dancing in “Tilt Brush” turned out to be too ambiguous, while the experience of playing “Space Pirate Trainer” was too prescribed for the dancers. From my external perspective to the dancers’ experience, watching them working in “Tilt Brush” was too messy, while watching them in “Space Pirate Trainer” was too explicit. Referring again to Dewey, expression is a development of meaning. To make the dancers’ movements expressive, we needed “to stay by, to carry forward in development, to work out to completion” (Dewey 65). I wanted the dancers to add another layer of mental images that related to the images of the virtual world. I wanted to give the dancers a way to be responsive — rather than reactive — to the VR environment.

Ultimately, the initial problems for staging dance in VR became the motivating principles of the choreography for performance.

NM: The research context helped me to reflect on my choices when integrating with the VR, to gain a better distance to VR, and it ultimately opened up new practices of engagement. Dealing with the theoretical aspects of immersion allowed me to better understand the emotional challenges I faced. It also opened up new ideas for how my dance could engage with technology.

CS: This tension you describe overall is an interesting difference: for gamers, the virtual world is usually a given — they interact within the parameters prescribed by the game system. As a dancer, you might have perceived that as a restriction. From a gamer’s point of view, it frames and informs the gamer of possible interactions. With VR, the focus on the body moved center-stage, as it became the main controller of the virtual world. In order to play a game, gamers suddenly had to immerse their entire bodies and use them to control their experience (Lanier 2017). Effectively, VR gamers became increasingly aware of and used their bodies in completely new ways (Pallavicini 2018). It could be called the revelation of the body to gamers; in a way, you as dancers were doing a reverse movement here by enacting the suspension between the virtual and the actual with your dancing bodies.

RM: Our interdisciplinary project questioned established frames of performance and technology. Negotiating the limits of theatrical form itself has had a privileged place in theatre history (Fischer and Greiner 2007; Hornby 1985; Lehmann 1999; Puchner 2010). Theatrical performance provides and breaks aesthetic frames in order to explore the status of reality and illusion as such. In doing so, theatrical performance offers a space to negotiate how thought and embodiment interact to create knowledge. Virtual reality provides another opportunity to experiment with how to frame reality in the face of digital technology, shifting the discussion to the performative potential of immersive environments. The cognitive transfer between body and mind is intricately interlinked with understanding how technology reshapes core aesthetic concepts of performance (Causey 2009; Bay-Cheng 2010). PwVR did both by playing with the parameters of being in a virtual world by multiplying the existence of co-present virtual spheres. The performance did not so much offer an immersive experience as experiment with what is at stake in the experience of immersion, because the dancers were on display in their negotiation of dancing across these different realities.

PwVR experimented with immersion as a theatrical and as a technological tool to capture the cross-media transfers and interferences that shape hybrid performance practices. We used dancing in and with VR to design a set of layered immersive interactions that set up a laboratory to investigate, practice, and contemplate different kinds of manifestations for immersion. To return to Janet Murray: immersion is a metaphorical term for a psychological response to a transformative experience (98-99). At the same time, “diving into” implies creative attunement; “we do not suspend disbelief so much as we actively create belief” (Murray 110). Creating immersion is an aesthetic labor, which integrates sensitivity and skill (Dewey 47). As an interdisciplinary project, PwVR dealt with a variety of know-hows, amongst them VR technology and embodied techniques of the dancers. In order to collaborate, we needed to play with our knowledge-systems and to emphasize how they could coexist and intertwine, since it was vital for our experiment to actively enable a process of “creating belief.” Our chain-letter format in this article sets out to capture our own process of dialogical exchange that shaped our collaborative processes throughout the devising period of PwVR-performance. It highlights collaboration not as a process of merging minds but rather as a multiplication of realities and perspectives that continuously engage and actively seek to interact with each other; it’s a process of interference and struggle rather than unification.

Likewise, our object of research, immersion, is multiple. It can be evoked by a whole range of performative and technological strategies. Allowing different kinds of immersive practices — here dance and VR — to encounter each other, creates a doubling that opens up a transitional or comparative space in which moments of immersion alternate with moments of reflection; creative making and critical thinking are not opposed but interweave with one another. The multiplication of virtual and actual stages ultimately created a space to push both the boundaries of interacting with technology and with our own techniques of knowing. Immersion provides a useful metaphor for interdisciplinary collaboration, since it requires the collaborators to enter into the totally new world of another discipline and open up to alternate concepts and practices. In many ways, we shared each other’s perspectives and fields not just by relating to them intellectually but also by trying to re-experience ideas through the eyes of another.

The collaboration in PwVR highlights that collaboration extends what we know but also allows us to reconsider how we know by foregrounding both the work of metaphor and with it, the use of embodied knowledge practices. It also opened up the understanding that although the wonder of virtual reality lies in the completeness with which it takes over our perceptual experience, the human body can resist virtuality and foreground sensory information that emphasizes contemplation and freedom of the imagination.

Acknowledgments: “Playing with Virtual Realities” was carried out by gamelab.berlin as part of Image Knowledge Gestaltung, Cluster of Excellence of Humboldt-University of Berlin, funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG). The project was created in collaboration with Institute for Games, Hochschule der Medien Stuttgart, the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies, Free University of Berlin, and with the dance program at the University of the Arts, Philadelphia. The project is in association with the international network of Performance Philosophy. The premiere and the symposium of “Playing with Virtual Realities” took place at DOCK 11 Berlin, between January 25-28, 2018.

Project director and choreographer: Einav Katan-Schmid

Dancers-researchers: Lisanne Goodhue and Nitsan Margaliot

Child performer: Aurica Mosse

Technical assistance-researchers: Meik Ramey and Norbert Schröck

Creative team-researchers: Sabiha Ghellal, Ramona Mosse, Christian Stein and Thomas Lilge

Benford, Steve, and Gabriella Giannachi. “Interaction as Performance.” Interactions, vol. 19, no. 3, 2012, 28-43. https://doi.org/10.1145/2168931.2168941.

Calleja, Gordon. In-game: Immersion to Incorporation. MIT Press, 2011.

Carter, Paul. Material Thinking. Melbourne University Press, 2004.

Causey, Matthew. Theatre and Performance in Digital Culture: From Simulation to

Embeddedness. Routledge, 2009.

Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. FLOW: The Psychology of Optimal Experience. Harper & Row, 1990.

Dewey, John. Art as Experience. Perigee Books, c1934, 1980.

Eco, Umberto. The Role of the Reader: Explorations in the Semiotics of Texts. Indiana University Press, 1979.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. The Transformative Power of Performance: A New Aesthetics. Translated by Saskya Jain, Routledge, 2008.

Forsythe, William, and Nik Haffner. William Forsythe: Improvisation Technologies: A Tool for the Analytical Dance Eye. ZKM Digital Arts Edition, Zentrum für Kunst und Medientechnologie Karlsruhe, 2012.

Gallagher, Shaun, and Robb Lindgren. “Enactive Metaphors: Learning Through Full-Body Engagement.” Education Psychological Review, vol. 27, 2015, pp. 391–404. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9327-1

Gaver, William W., Jacob Beaver, and Steve Benford. “Ambiguity as a Resource for Design.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 233–240. CHI ’03. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1145/642611.642653.

Ghellal, Sabiha. The Interpretative Role of an Experiencer: How to Design for Meaningful Transmedia Experiences by Contrasting Ambiguous Vs. Prescribed Qualities. Aalborg Universitetsforlag, 2017. https://doi.org/10.5278/vbn.phd.tech.00006.

Grau, Oliver. Virtual Art: From Illusion to Immersion. MIT Press, 2003.

Held, Richard M. and Nathaniel I. Durlach. “Telepresence.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, vol. 1, no. 1, 1992, pp. 109–112.

Indurkhya, Bipin. Metaphor and Cognition: An Interactionist Approach. Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1992.

Jarvis, L. Immersive Embodiment. Theatres of Mislocalized Sensation. Palgrave Macmillan, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-27971-4_1

Johnson, Mark. The Body in the Mind. The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. Chicago University Press, 1987.

Katan, Einav. Embodied Philosophy in Dance; Gaga and Ohad Naharin’s Movement Research, Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Koleva, Boriana, Ian Taylor, Steve Benford, Mike Fraser, and Chris Greenhalgh. 2001. “Orchestrating a Mixed Reality Performance.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. March 2001, pp 38–45. https://doi.org/10.1145/365024.365033

Lanier, Jaron. Dawn of the New Everything: Encounters with Reality and Virtual Reality. Henry Holt, 2017.

Lakoff, George. Women, Fire and Dangerous Things. What Categories Reveal About the Mind. The University of Chicago Press, 1987.

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. University of Chicago Press, 1980.

Lehmann, Hans-Thies. Postdramatic Theatre. Translated by Karen Jürs-Munby, Routledge, 2006.

Lombard, Matthew, and Matthew T. Jones. “Identifying the (Tele)Presence Literature.” Psychology Journal. vol. 5, no. 2, 2007, pp. 197-206.

Machon, Josephine. Immersive Theatres: Intimacy and Immediacy in Contemporary Performance. Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Mapping Intermediality in Performance. Edited by Sarah Bay-Cheng, Chiel Kattenbelt, Andy Lavender, and Robin Nelson, Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Translated by Colin Smith, Routledge, c1945, 2002.

Minsky, Marvin. Telepresence. OMNI magazine New York, 1980.

Murray, Janet. Hamlet on the Holodeck. The Future of Narrative in Cyberspace. MIT Press, 1998.

Noe, Alva. Varieties of Presence. Harvard University Press, 2012.

Norman, Don, Jim Miller, and Austin Henderson. “What You See, Some of What’s in the Future, and How We Go About Doing It: HI at Apple Computer.” Conference Companion on Human Factors in Computing Systems, p. 155. CHI ’95. New York, NY, USA: ACM, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1145/223355.223477.

Norman, Don. The Design of Everyday Things: Revised and Expanded Edition. Basic Books, 2013.

Pallavicini, Frederica, Ambra Ferrari, Andrea Zini, Giacomo Garcea, Andreas Zanacchi, Gabriele Barone, and Fabrizia Mantovani. “What Distinguishes a Traditional Gaming Experience from One in Virtual Reality? An Exploratory Study.” In Advances in Human Factors in Wearable Technologies and Game Design. Edited by Tareq Ahram and Christianne Falcão, AHFE, 2017. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 608. Springer, 2018.

The Play within the Play: The Performance of Meta-theatre and Self-reflection. Edited by Gerhard Fischer and Bernhard Greiner, Rodopi, 2007.

Puchner, Martin. The Drama of Ideas. Oxford University Press, 2010.

Rekimoto, Jun. “Organic Interaction Technologies: From Stone to Skin.” Commun. ACM. vol. 51, no. 6, 2008, pp. 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1145/1349026.1349035.

Schnipper, Matthew. “Seeing is Believing: The State of Virtual Reality.” The Verge Website. https://www.theverge.com/a/virtual-reality/intro. Accessed February 26, 2018.

Sheridan, Thomas B. “Musings on Telepresence and Virtual Presence.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. vol. 1, no. 1, 1992, pp. 120–26. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.1992.1.1.120.

Sherman, William R., and Alan Craig. Understanding Virtual Reality: Interface, Application, and Design. Morgan Kaufmann, 2003.

Shneiderman, Ben. “Direct Manipulation: A Step Beyond Programming Languages.” Computer. vol. 16, no. 8, 1983, pp. 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1109/MC.1983.1654471.

Slater, Mel, and Sylvia Wilbur. “A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments.” Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments, vol. 6, no. 6, 1997, pp. 603–16. https://doi.org/10.1162/pres.1997.6.6.603.

Stanney, Kay M. and Wallace Sadowski. “Presence in Virtual Environments.” Handbook of Virtual Environments: Design, Implementation, and Applications, ed. Kay M. Stanney, 791–806. CRC Press, 2002.

Tekinbaş, Katie S., and Eric Zimmerman. Rules of Play: Game Design Fundamentals. MIT Press, 2003.

Valéry, Paul. “Philosophy of the Dance.” Salmagundi, vol. 33/34, 1976, pp. 65-75. http://jstor.org/stable/40546919. Accessed 2 December 2020.

Van Manen, Max. Researching Lived Experience: Human Science for an Action Sensitive Pedagogy. Routledge, 2016.

Vyas, Dhaval, and Gerrit C. van der Veer. “Experience As Meaning: Some Underlying Concepts and Implications for Design.” Proceedings of the 13th European Conference on Cognitive Ergonomics: Trust and Control in Complex Socio-technical Systems: pp. 81–91. Association for Computing Machinery, 2006.

VR Technology and Applications Cited

HTC VIVE, HTC Corporation accessed 30 January 30 2018 http://htcvive.com/

Lone Echo, Oculus Rift, accessed 28 February 2018 https://oculus.com/lone-echo/

Masterpiece VR, Oculus Rift, accessed 28 February 2018 https://masterpiecevr.com/

Space Pirate Trainer, I-Illusions, accessed 30 January 2018 http://spacepiratetrainer.com/

TiltBrush, Google VR, accessed 30 January 2018 https://tiltbrush.com/